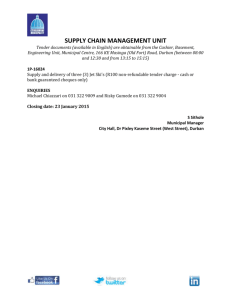

Martel Building Ltd. v. Canada, [2000] 2 S.C.R. 860 Her Majesty The

advertisement

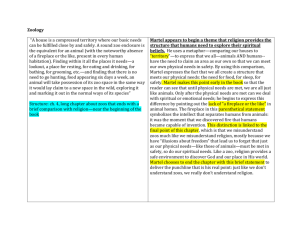

![Martel Building Ltd. v. Canada, [2000] 2 S.C.R. 860 Her Majesty The](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008326877_1-d19b7d6ad755e9ecd686ee8face736de-768x994.png)