TV Drama Series Development in the US

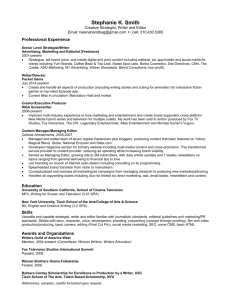

advertisement