Music in television advertising and other persuasive media

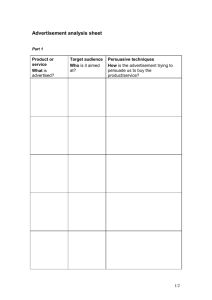

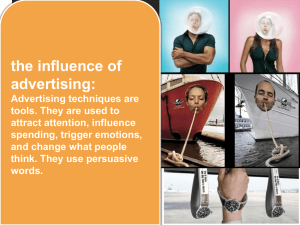

advertisement