Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals

advertisement

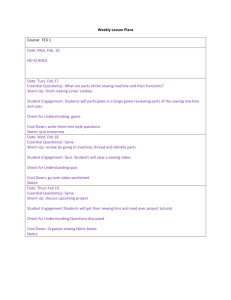

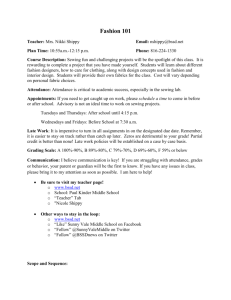

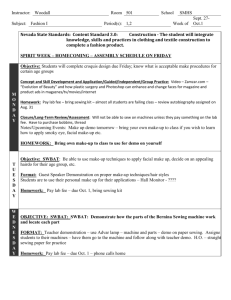

SUMMARY APPLIED RESEARCH 䉬 Examines audience-centered writing strategies in two very early sewing machine manuals 䉬 Considers the difference between nonsexist and gender-neutral writing 䉬 Concludes that avoiding sexism in technical writing may sometimes be impossible Authority and Audiencecentered Writing Strategies: Sexism in 19 -century Sewing Machine Manuals th KATHERINE T. DURACK INTRODUCTION A s practitioners of technical communication, we are frequently advised to “know our audience” so that we may best meet its needs and expectations in the documents that we produce. By doing so, we shall be better able to accommodate to our readers the technologies about which we write (Dobrin 1983, 1989). Understanding the reader is key to effective document design (Rubens 1986; Schriver 1989, 1997), to developing strategies for revision (Carroll, Smith-Kerker, Ford, and Mazur-Rimetz 1987, 1988; Flower, Hayes, and Swarts 1983; Keller-Cohen 1987; Matchett and Ray 1989; Redish, Battison, and Gold 1985), and to determining the appropriate writing style (Brockmann 1986; Mirel, Feinberg, and Allmendinger 1991); it is crucial to establishing a document’s readability (Duin 1988, 1989; Huckin 1983), to evaluating product usability (Norman 1990; Quiepo 1991), and to writing texts for audiences of different cultures (Mackin 1989; Matsui 1989). As writers charged with fashioning effective communication, we are advised to shape our texts according to the practical and cultural needs of our audiences, yet at the same time, admonished to write in such a way that our texts are nonsexist (Dell 1989; Frank and Treichler 1989) and that the science and technology our documents depict is “genderfree” (Lay 1994). Leaving aside the question of whether science and technology are indeed “gender-neutral” (an idea contested by many feminist scholars of science and technology), the question we must ask is to what extent is it possible to reflect the concerns and interests of an audience and yet construct texts that are gender-neutral in a society that has historically divided labor—and correspondingly, the technologies used—according to the worker’s sex? 180 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 . . . to what extent is it possible to reflect the concerns and interests of an audience and yet construct texts that are gender-neutral in a society that has historically divided labor— and correspondingly, the technologies used—according to the worker’s sex? We may presume that the fact-based, often impersonal, “corporate” voice employed in many technical documents obtains some level of “objectivity,” but as Sauer (1993) and others have demonstrated, both impersonal style and standardized formats can mask culpability in disaster reports, simultaneously serving the needs of powerful groups and silencing the concerns of others (see also Herndl 1991). It is easy to believe that texts associated with controversial events, despite poses of objectivity, may become implicated in efforts to lay blame or conceal accountability. But what of those documents whose purpose is merely to instruct someone in the use of everyday technology—a Manuscript received 7 November 1997; revised 14 January 1998; accepted 16 January 1998. APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals Durack Figure 1. Sewing machine manufacture increased significantly during the 1850s (data from Bourne [1895], p. 530). blender or perhaps an electric screwdriver? Is it possible to write nonsexist prose for an audience defined (in large part) by gender? Even though many of us subscribe to the notion that technology itself is “neutral” and that it is the purposes to which technologies are applied that reveal biases, this supposed neutrality has been questioned by the work of scholars of technology (see Postman 1993; among feminist scholars, Kramarae 1988a; Cowan 1983; Cockburn 1988; and Wajcman 1991 are significant). Understanding how technologies and writings about them reflect and reinforce cultural values and beliefs has recently emerged as an area of interest in the study of technical communication (for discussion of feminism and technical communication, see Allen 1991 and Lay 1994; for broader treatment of social theory and technical communication, see Duin and Hansen 1996). In this article, I investigate questions of authority and sexism in technical writing from the mid-nineteenth century. I chose the historical focus to attempt to overcome the difficulty Bernhardt notes with detecting sexism in contemporary documents, namely that “for those immersed in the culture, sexism can simply be difficult or impossible to see” (1992, p. 218). My goal is to determine what, if any, textual strategies writers used to accommodate the new, “mascu- line” technology, the sewing machine, to its female users. In particular, I am interested in whether authors acknowledged women’s authority and sought to bridge gaps between their knowledge about sewing and men’s knowledge of machines, gaps that resulted from the separation of spheres and division of labor based on sex. My assumption was that the burden for such accomodation would be greatest in the earliest days of market penetration and expansion (see Figure 1), and might be revealed by audience-centered writing strategies similar to those advocated by current technical writing theory (by the use of situated cases, examples, or scenarios). My efforts are focused on early sewing machine manuals and the extent to which content and textual characteristics meet two general recommendations: 1. Good technical writing involves readers and anticipates their goals. 2. Good technical writing forges connections between new and existing knowledge. Schriver (1997) observes that “the first decision people make when confronted with a document is whether or not to read” (p. 164). To encourage readers, documents should be visually appealing and should help the reader accomplish real goals (Schriver 1997; Duin 1988). Good technical Second Quarter 1998 • TechnicalCOMMUNICATION 181 APPLIED RESEARCH Durack Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals prose is “structured around a human agent performing actions in a particularized situation” (Flower, Hayes, and My goal is to determine what, if any, textual strategies writers used to accommodate the new, “masculine” technology . . . to its female users. Swarts 1983, p. 42); technical writing should provide “questions, examples, illustrations, and metaphors” to involve readers in the text (Duin 1988, p. 192). Current theory also advises writers to forge connections between existing and new knowledge (Duin 1988, 1989; Huckin 1983). It seems likely that before the introduction of the sewing machine, texts were seldom used in teaching home sewing, as the requisite skills were most typically learned by girls from their mothers in apprenticeship fashion, starting with easier tasks—plain sewing on short, straight edges—and working up to greater challenges such as cutting, fitting, or “turning” clothing (Strasser 1982; Beecher and Stowe 1869). Instruction in technique was rewarded through emotional means (for young girls, with toy dolls and housekeeping play; for older girls and women, through the admiration of others combined with the opportunity for feminine companionship). But the invention of the home sewing machine greatly changed the nature of the task, requiring of its users a different sort of mechanical skill than previously needed for household sewing. Did early technical writers employ knowledge of the products of women’s household sewing (linens and clothing) and its emotional rewards, and claim an increase in these results with the use of the machine? Did they use textual strategies such as examples to “situate” the machine in the household? To what extent were these early technical writers cognizant of the differences in knowledge needed to sew by machine versus that necessary for sewing by hand? Did they seek to bridge these gaps in knowledge within the text? To answer these questions, I examined selected texts for the following elements: 䉬 Use of metaphors or examples to situate the machine in the household 䉬 Recognition of the goals of women’s household sewing, indicated by references to its products (linens and articles of clothing) 䉬 Recognition of sewing as a collaborative task reflected in tone, word choice, and metaphors that personify the machine, casting it as a feminine collaborator 182 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 䉬 Recognition of sewing as a “labor of love” by promises of emotional reward (improved relationships, elevated social status, admiration of others), as yielded by machine sewing 䉬 Explication (prose or illustration) of technical mechanical terms (my assumption being that such terminology would be unfamiliar to most 19thcentury female readers, unschooled in the mechanical arts) To determine the extent to which notions of audience and audience needs are reflected in early sewing machine instructions, I examined publications from the Warshaw Collection in the Archives Center at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. I established three criteria for the instructions selected for analysis: 䉬 They should be published near or during the first expansion of the industry (1858 –1860), when manufacturers were beginning a new focus on reaching the household market (Hounshell 1984; see also Figure 1). 䉬 They should be published prior to the beginning of the Civil War. The Civil War changed the rhetoric of the sale— characterizing sewing by machine as women’s patriotic duty (Brandon 1977)—as well as the dynamics of competition among the major sewing machine manufacturers (At the start of the war, Wheeler and Wilson, the leading manufacturer, suffered a dramatic decline in production, while the globally diversified Singer continued steady growth throughout.) 䉬 The manual should be for a home rather than industrial model machine. Figure 2 shows documentation from the three major 19thcentury sewing machine manufacturers available to researchers in the Warshaw Collection. Many of the documents are undated; dates of publication for undated documents were estimated based on information about the manufacturing dates of the sewing machines they describe To determine the extent to which notions of audience and audience needs are reflected in early sewing machine instructions, I examined publications from . . . the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals Durack Figure 2. Selected 19th-century sewing machine instructions. Washaw Collection of Business Americana, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. and expert opinion on the clothing styles worn by women shown at the machines. All but two of the documents—a manual published by Grover and Baker in 1859, and an undated leaflet published by Singer—were estimated to have been published after the Civil War and were therefore eliminated from my analysis. The first document, for the Grover and Baker machine, is a 38-page booklet (approximately 4 ⫻ 6 inches), which, by its contents, appears to have two purposes: both to support the sale of the machine and to instruct the user in its use. Its contents and the pages devoted to each are listed below: 䉬 “A Home Scene” (pp. 1– 6) 䉬 “Directions for Using the Family Sewing Machine” (pp. 7– 8) 䉬 “How to Prepare for Work, and Directions for Sewing” (pp. 9 –13) 䉬 “Relative Merits of the Sewing Machine Stitches” (pp. 14 –20) 䉬 Sewing machine models and prices (pp. 20 –26) 䉬 “A Few Names of Purchasers” (pp. 27–28) 䉬 Testimonials (pp. 28 –37, plus inside front cover) The document includes a number of illustrations, none of which appear in the two sections titled “Directions.” Figure 3 shows a two-page spread from the Grover and Baker manual. The second document, directions for using the Singer machine, is a leaflet of four 81⁄2 ⫻ 11 inch pages (see Figure 4). It also is multi-purpose, including both sales and instructional material; additionally, the document identifes two purposes for the machine (“For Family and Light Manufacturing Purposes”). Enumerated directions appear on the first three pages, and the final (back) page of the leaflet is an advertisement proclaiming the merits of the machine, as well as listing Second Quarter 1998 • TechnicalCOMMUNICATION 183 APPLIED RESEARCH Durack Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals Figure 3. A two-page spread from the 1859 Grover and Baker sewing machine manual. The left-hand page (p. 8) shows portions of the “Directions for Using the Family Sewing Machine”; a new section, “How to Prepare for Work, and Directions for Sewing,” begins on the opposite page. Washaw Collection of Business Americana, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. available supplies and information for correspondence with the company. The only illustration (of a woman seated at the machine) appears on the front of the leaflet. Before turning to the analysis, it would be useful to understand these documents and the machines they describe in their historical context; for that reason I turn now to a short history of the sewing machine and its introduction into the household. A BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE EARLY HISTORY OF SEWING MACHINES The sewing machine, when first commercially introduced in the early 1850s, was as “awe-inspiring” and extraordinary then as it is ordinary now (Cooper 1976, p. vii). A completely new technology, it revolutionized an ordinary task—sewing—and in doing so provided impetus not only to the burgeoning retail clothing industry but to numerous manufacturing concerns ranging from bookbinding to the production of flags and sails (Bourne 1895). Because of the machine’s complexity and the ownership of key patents by competitors, the early industry was plagued by patent disputes and litigation. A solution came in 1856 when Orlando Potter, president of Grover and Baker, suggested that Elias Howe, I. M. Singer and Co., and Wheeler and Wilson join forces to form a “Combination,” 184 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 Figure 4. The front page of a leaflet describing the use of an early Singer Family Sewing Machine. Washaw Collection of Business Americana, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. the first patent pool (Cooper 1976, p. 41). This action served both to compensate the patent-holders and to limit competition outside the membership of the Combination to 20 additional licensees until its conclusion in 1876 with the expiration of the last of the patents. Although the first machines were developed for the manufacturing market, in 1851 Wheeler and Wilson led the industry in introducing sewing machines for private ownership in the home (Cooper 1976, Hounshell 1984). Grover and Baker soon followed, as did I. M. Singer in 1858 (Cooper 1976). Once the problem of patent litigation had been addressed, two other impediments had to be overcome for the machine to penetrate the household market: its high cost and the cultural belief that women and machines were fundamentally incompatible. In 1859, a household sewing machine was a luxury. At $75 to $100 per machine (Cooper 1976; A home scene 1859), its cost was nearly equivalent to the annual U.S. per APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals Once the problem of patent litigation had been addressed, two other impediments had to be overcome for the machine to penetrate the household market: its high cost and the cultural belief that women and machines were fundamentally incompatible. capita income of $115 in 1860 (Norris 1990, p. 12). The problem of cost was met on two fronts. First, through the innovative “hire-purchase” plan conceived in 1856 by Edward Clark of I. M. Singer and Co. (Bourne 1895), consumers were extended credit and permitted to “pay a dollar or two a month until the full amount of the sale was paid” (Cooper 1976, p. 58). Second, manufacturers sought to reduce the cost of production. The early sewing machines were painstakingly made in small batches, then finished and assembled by hand, one by one (Hounshell 1984). To meet increasing demand for machines, several sewing machine companies (first Willcox and Gibbs, then Wheeler and Wilson) pioneered more sophisticated techniques, building on and improving practices from armory manufacture (Hounshell 1984). The new manufacturing technology involved building special-purpose machines (such as milling machines and lathes) designed for manufacturing particular parts. Such machines, combined with measures and gauges for evaluating whether the resulting parts met established criteria, produced standardized parts that were claimed by the manufacturers to be interchangeable and that required less hand-fitting by individual craftsmen, resulting in greater similarity among machines of the same model as well as less costly repairs for consumers. Though slow to accept this “American System” of interchangeable manufacturing, I. M. Singer and Co. was the first to innovate sales strategies for overcoming “the public’s suspicion of sewing machines” (Cooper 1976, p. 34). Brandon (1977) reports that manufacturers had to confront the widely held view that “women do not use machines” (p. 70). In addition, the introduction of domestic laborsaving devices was both novel and threatening during this era when fewer than 15% of women worked in the wage labor force (Kessler-Harris 1982) and many women were noisily agitating for the rights to own property and to vote (Schneir 1972). Singer and the other manufacturers had to Durack counter concerns about how women would use the newfound free time promised by the machine (Brandon 1977) as well as attacks on the machine that . . . often took the form . . . of trying to prove that there were certain things for which women as a sex were fundamentally unsuited. Women, for example, could not and should not try to work on complex machinery. It would be beyond them and would end in tears. (Brandon 1977, p. 122) In seeking a middle-class household market for their machines, manufacturers also had to be concerned about their association with the widely publicized plight of the sewing woman and the unsavory reputations of employers in the retail clothing industry. Sewing women suffered abject poverty, a fact that had become a “national scandal” in the early part of the 19th century (Kessler-Harris 1982, p. 30). Attention to the poverty of the sewing woman continued throughout the century, with interest revived by works such as Thomas Hood’s “Song of the shirt,” first published in England in 1843 and an immediate sensation when printed in the U.S. in 1851 (Schneir 1972, p. 58). WOMEN AND HOUSEHOLD SEWING For generations prior to industrialization, sewing was an essential skill passed down from mothers to daughters; according to a popular etiquette book of the mid-19th century, “A woman who does not sew is as deficient in her education as a man who cannot write” (from The young lady’s friend, quoted by Strasser 1982, p. 132). Beecher and Stowe (1869) describe how a child might learn the craft, beginning with the promise of a doll’s bed and pillow once she had made a tiny bed quilt and the associated linens, then moving on to undergarments and clothing with the promise of a doll. By this strategy, “the task of learning to sew will become a pleasure; and every new toy will be earned by useful exertion” (p. 298). Furthermore, this strategy ensured that young girls were enculturated into the “never-ending productive labor that was compensated in part by a mission of love, a sense of craft satisfaction, and the sharing of a community of women” The new manufacturing technology involved building special-purpose machines (such as milling machines and lathes) designed for manufacturing particular parts. Second Quarter 1998 • TechnicalCOMMUNICATION 185 APPLIED RESEARCH Durack Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals (Strasser 1982, p. 126). Transforming yard goods into clothing was a task accomplished by housewives “with the help of their daughters and other female relatives” (Strasser 1982, p. 130). Sewing “provided [women] an approved way of talking and relaxing with family or friends while still working” (Kramarae 1988b, p. 149). Families with the income to do so hired seamstresses and dressmakers who might live with their employers for a period of time (Strasser 1982), and even women wealthy enough to hire seamstresses to complete all their household sewing “left their homes in the afternoons to join their charitable sewing circles” (p. 133). . . . there was little correspondence between the knowledge and skills a girl learned from her mother and those required to run the machine. Before 1860, the dressmaker employed by such a wealthy woman might also act as a personal companion, consulted by her mistress not just for her needlework skills, but for advice on fashion and etiquette (Baron and Klepp 1984). Feminine collaboration eased the drudgery of what must have seemed miles of plain sewing required to equip a household with all the necessary household linens, and collaboration was a necessity for constructing the day’s close-fitting fashionable clothing. During the time in question, a fashionable dress required several lengthy fitting sessions (Kidwell 1979). One of the significant challenges to the sewing machine’s development was that a successful mechanism could not mimic the hand; one consequence was that there was little correspondence between the knowledge and skills a girl learned from her mother and those required to run the machine. Sewing by hand and sewing by machine are very different tasks requiring different knowledge and skills. The hand stitcher uses very simple tools, and with these, she produces a wide variety of stitches: Beecher and Stowe (1869) ennumerate “overstitch, hemming, running, felling, stitching, backstitch and run, buttonhole stitch, chain-stitch, whipping, darning, gathering, and cross-stitch” (p. 353). The seamstress knew not just how to execute these stitches but when to employ them for different uses and what adjustments were required when working with different types of fabrics. In contrast, a machine of this era could make only a single type of stitch among the several necessary to complete a garment, and users had to determine when to employ the machine and how to incorporate its comparatively limited utility into the overall production process. Additionally, the early machines were fairly complicated (certainly much more 186 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 complex than simple needle and thread), and even machines of the same model varied greatly as a result of manufacturing processes and could be quite temperamental (Bourne 1895; “The modern seamstress” 1869). SEWING MACHINES, AUDIENCE, AND PERSUASION From the preceding, we can see that manufacturers faced several persuasive tasks: 䉬 To establish the household “necessity” of the laborsaving device 䉬 To overcome prejudice about women’s mechanical ability 䉬 To “sanitize” the household sewing machine in contrast to its use in industry 䉬 To displace or redefine women’s authority in the context of sewing Additionally, they had to educate women about differences between machine sewing and hand sewing; Parton (circa 1872) reports that the “purchaser had to take lessons as on the piano” (p. 14). Early on, knowledge of one brand or model of sewing machine was not necessarily transferable to others, as during this period three very different types of stitching mechanisms (producing a “lock-stitch,” a “chain-stitch,” and a “double-chain stitch”) competed for market share. Manufacturers responded to these needs in their sales and marketing strategies, and Isaac Singer is credited with pioneering new methods for selling sewing machines to Victorian customers. According to Hounshell (1984), by 1851 the company had initiated a “vigorous marketing program which involved using trained women to demonstrate to potential customers the capabilities of the Singer machine” (p. 84). At the same time, the company built “lavishly decorated show rooms . . . rich with carved walnut furniture, gilded ornaments, and carpeted floors, [which were] places in which Victorian women were not ashamed to be seen” (Cooper 1976, p. 34; another description appears in Parton circa 1872). Other companies adopted the same strategy, building luxurious showrooms and hiring pretty young women to serve as “instructresses” and to demonstrate the machines in storefront windows These marketing strategies clearly demonstrate that manufacturers were sensitive to the attitudes and needs of the consumer, but was this information used to develop sewing machine instructions? APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals (no doubt attracting the attention of both male and female passers-by). These marketing strategies clearly demonstrate that manufacturers were sensitive to the attitudes and needs of the consumer, but was this information used to develop sewing machine instructions? The Singer manual’s only attempt to attract and respond to the specific needs of a female audience is its initial illustration; it is a document that exemplifies “machine-centered” technical writing. TEXT ANALYSIS The two pre-Civil War manuals, published by Grover and Baker and I. M. Singer and Co., stand in marked contrast to each other. The Singer manual’s only attempt to attract and respond to the specific needs of a female audience is its initial illustration; it is a document that exemplifies “machine-centered” technical writing. Human agents are rarely named because the majority of sentences are passive or imperative; it is the machine or one of its parts that serves as the subject of most sentences. In very few cases is the user of the machine even identified. When this does occur, she is referred to impersonally as the operator (six times) or as you (four times). Of these instances, four occurrences indicate positional relationship to the machine (something should be turned toward or away from the user, something can be found on the machine just opposite the user) and two pertain to subsequent action (“when you thus have the needle in its proper position” [p. 1] and “when you wish to take goods from the Machine” [p. 3]). In one instance, it is the machine that “enables the operator” (p. 1) to perform a task; in only two instances is the user indicated as acting on the machine: “there is a spring which can be removed . . . and substituted by the operator” (p. 2) and “fix the draw or tension . . . as you want it” (p. 3). The tone adopted by the writer is commanding and demands that the reader cater to the needs of the machine; the reader is expected to respond to numerous musts and shoulds (often italicized or printed in capital letters): “The Machine . . . MUST BE OILED . . .” (p. 1); “the center of the foot must be placed directly over the cross-piece [of the treadle]” (p. 1); “this spring . . . must be pressed down” (p. 3); “THE BEST Durack SPERM OIL, AND NOTHING ELSE, SHOULD BE USED” (p. 1). And while the author states that there are “twenty-one places about the Machine and stand to be oiled” (p. 1), these places are neither listed nor illustrated, with the consequence that the user must determine these locations by inspection. The 14 enumerated sections (most of them single paragraphs) do not describe a sequence of tasks pertaining to sewing itself, but rather to information describing the machine or tasks pertaining to its set up, proper adjustment, and maintenance (see Table 1). The vocabulary employed is heavily technical (using terms such as friction, crank, shaft, driving belt, and inclined plane) with the necessary inclusion of sewing terms such as spools, thread, seam, and hem (in reference to the proper set up and functioning of the hemming guide attachment). In a very few instances, some effort has been made to explain the terminology, usually by comparison (five times) to a more common term: “hinge or fulcrum” (p. 2); “turned to the left or unscrewed” (p. 3). And there are a few implicit definitions: a reference to friction is followed, a few lines later, by a requirement to oil the machine “on every place where one part rubs against another” (p. 1), and the driving belt is described as the “belt which communicates motion to the machine” (p. 3). No reference is made to any article produced by use of the machine except in the most abstract sense, as goods, cloth, ordinary light work, and heavy work. There are no examples given, nor is there any recognition of the emotional rewards many women associated with sewing. Even in the final page of the document (a full-page advertisement), the value of the machine to the household user is phrased primarily in economic terms: The purchasers of Machines, whose daily bread it may concern, will find that those having the above qualities not only work well at rapid as well as slow rates of speed, but last long in the finest possible working order. Our Machines . . . will earn more money with less labor than any others, whether in imitation of ours or not. In fact they are cheaper than any other machine as a gift. (Emphasis in original; p. 4) Those rare instances of personification occur within the advertisement only, wherein the machine is described as being finished in “chaste and exquisite style” (emphasis added p. 4). There are no examples given, nor is there any recognition of the emotional rewards many women associated with sewing. Second Quarter 1998 • TechnicalCOMMUNICATION 187 APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals Durack TABLE 1: TOPIC SEQUENCE OF SINGER DIRECTIONS AND “A HOME SCENE” FROM THE GROVER AND BAKER MANUAL Singer Directions Grover and Baker “A Home Scene” Oiling the machine [maintenance] Operating the treadle [operation] Oiling the shuttle spooler [maintenance] Feeding fabric through the machine [operation] Operating the treadle [operation] Adjusting thread tension [operation] Setting the Needle [set-up] Setting the vertical needle [set-up] Threading the Shuttle [set-up] Threading the machine [set-up] Threading the Needle [set-up] Threading the circular needle [set-up] The Check-Spring Lever [problem-solving] Removing work from the machine [operation] Changing foot-bar pressure [set-up] Removing a seam [problem-solving] Feed Motion [operation] Oiling the machine [maintenance] Removing goods from the machine [operation] Tension of the Two Threads [problem-solving] The Driving Belt [problem-solving] Oil the machine if it runs hard [problem-solving] Hemming-Gauges [operation] 䉬 Bracketed text denotes type of topic. The instruction booklet for the Grover and Baker sewing machine is greatly different. Although at first glance this document appears to include fewer pages of instruction for users than does the Singer document (just two short pages of “Directions for Using the Family Sewing Machine”), in fact three different sections of the booklet are devoted to instructing the user. The “Home Scene” at the beginning of the document describes in narrative form the circumstances leading to the purchase of the machine, introduces the machine into the household, establishes feminine competence with the technology, and claims long-term benefits of introducing the machine into the household. This short vignette is more than sales propaganda: the central portion of the story is essentially an extended “scenario” that revolves around a 188 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 series of problems posed by Mr. Aston, who attempts unsuccessfully to operate the device and whose difficulties are repeatedly solved by Mrs. Aston: Mr. A., after tea, jocosely remarked: “I think I will make a good operator, Mary;” and seating himself at the machine, said: “See me; I take hold of the lower part of the wheel with my right hand, and pull it in a downward direction. What now? it does not run in the same manner in which I started it.” “Well,” answered Mrs. Aston; “you do not keep up a regular motion on the treadle with your foot. While interested in watching the needle, the motion of your foot is arrested, and the wheel runs the contrary way before you are aware. To avoid this, keep as good time as APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals if you were playing a melodeon: press first on the heel, then on the forepart of the foot, without raising the toes.” (Emphasis in original; p. 3) The instruction booklet for the Grover and Baker sewing machine is greatly different. Through this playful dialogue, many of the difficulties the novice user might experience arise and are solved by Mrs. Aston: 䉬 Why the fabric doesn’t feed properly through the machine 䉬 How to determine and correct the five possible causes of breaking thread 䉬 When and how to change the thread 䉬 How to remove work from the machine 䉬 How to remove a seam 䉬 How to maintain the machine In many cases, Mrs. Aston considers more than one possible cause and correction for the problems Mr. Aston presents: for instance, breaking thread can be caused by tension that is too tight, by the absence of a cloth washer on the upper spindle, by crowding the thread against the needle-hole, by thread too large to lie in the groove of the needle, or by a rough circular needle, all possibilities that Mrs. Aston considers and many of which she describes. Most of these same topics are discussed in the Singer instructions, but in the Grover and Baker manual, the sequence is determined by the likely order in which a user of the machine would encounter each task (see Table 1 for a comparison of topics and sequences) and presented in the context of user action. While modeling problem-solving techniques, this dialog also establishes the female user as expert and likens use of the machine to activities a properly educated middleclass woman might be familiar with (for example, through comparing the appropriate treadle action to that required for playing the melodeon). Rewards for using the machine are portrayed as emotional and involve relationships: the cover proclaims that “A good sewing machine lightens the labor and promotes the health and happiness of those at home,” a statement seemingly verified by the peace it brings to the household, quieting the older children who become “silent with curiosity” and lulling the baby into “sweet slumber” with its “gentle murmuring sound” (p. 3). At the end of the story (some 2 years after the machine’s purchase), the sewing machine has helped Mrs. Aston provide the family with an “elegant and stylish wardrobe” admired “on the promenade, at the church, or other public Durack places” (p. 6). To the delight of her husband, Mrs. Aston again has time for music-making and merry evening pastimes. The congenial tone established in the story/scenario is reinforced throughout the rest of the document, even in the less personal “Directions for Using the Family Sewing Machine.” Consider, for instance, the explanation pertaining to the machine’s driving belt from the Singer instructions: The Driving Belt.—The belt which communicates motion to the Machine should always be tight enough to move the Machine without slipping, and no tighter than is requisite to perform that office. Should it become too loose, it may be tightened to a certain extent by unscrewing the nut that holds the stud on which the large wheel revolves. When the nut is thus loosened, pull the large wheel backward, so as to make the belt tighter; hold it fast until the nut is screwed back so as to hold the wheel firmly. Should the belt happen to stretch beyond the capacity of the adjustment last described to tighten it, then the belt must be shortened. (p. 3) . . . this dialogue . . . establishes the female user as expert and likens use of the machine to activities a properly educated middle-class woman might be familiar with . . . . Similar instructions appear in the Grover and Baker manual: THE BELT OF THE BALANCE WHEEL Sometimes stretches, and the wheel will then fail to move the working part of the machinery. It may be tightened by first unscrewing the thumb-screw under the crossbar, shoving the wheel to the right, and then screwing tight again. Some of the machines have the wheel placed within a frame, fastened to the side of the cross-bar with screws, which may be treated in the same manner. (p. 8) While the Singer instructions begin by describing a state that should always be maintained (“The belt . . . should always be tight enough” [p. 3]), the Grover and Baker discussion begins with a statement of the problem as the user would experience it: the machine doesn’t work because the belt sometimes stretches (p. 8). Word choice also affects the tone: The Singer belt “perform[s] that office” of “communicat[ing] motion to the Machine” (p. 3) while the Grover and Baker belt simply “move[s] the working part of the machinery” (p. 8). Second Quarter 1998 • TechnicalCOMMUNICATION 189 APPLIED RESEARCH Durack Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals This congenial tone is reinforced in the next section of the Grover and Baker manual, “How to Prepare for Work and Directions for Sewing,” a section devoted to bridging hand sewing and machine sewing knowledge and technique. Here, the presumably female author identifies herself with the reader by use of “we”: No fear need be entertained that these sizes [of thread] will be too fine, when we take into consideration that the thread is crossed several times. (p. 9) This statement bridges the difference in thread choice appropriate for hand compared with machine sewing (the hand sewer would use heavier thread) but also explicitly reassures the reader (“No fear need be entertained”) and explains why the lighter thread is appropriate. The feminine identity of the author is further suggested by the use of “us” and a reference to “our grandmothers” in a section on “selvedges or overhand seams”: Instead of sewing the seam over and over, in the manner taught us by our good grandmothers, before the advent of sewing machines, a better plan is to lap the selvedges, and stitch one or two rows of stitching. (Emphasis added; p. 10) The author includes herself as a seamstress, respectfully acknowledges the conventional method, then tactfully suggests a newer technique. This section is replete with such direct comparisons between hand and machine sewing, with tactful suggestions for replacing old knowledge with new technique, and with recognition of the specific tasks for which a woman would need to use the machine by naming those products: “shirt” (p. 12), “skirt” (p. 11), and “bed-quilt” (p. 12). The reader is also given choices (on hemming with and without the hemming attachment) and friendly advice as in the following from the section on “crossing a seam”: . . . the crossing will be facilitated by pressing the seam flat, and rubbing a little white soap on the thick part. A small piece of soap kept in the work-basket will be found useful for softening the tough places which often occur in sewing. Many ladies follow this practice in hand sewing, where goods are hard to sew. (p. 12) Taken together, these three sections (“A Home Scene,” “Directions for Using the Family Sewing Machine,” and “Directions for Sewing”) are intended to equip the reader with all the information she needs to put the machine to work: The preceding directions for the use of the machines, and the preparation of work will materially aid the 190 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 The document seeks not to establish rapport with the reader, but rather dictates the terms and conditions of use. learner, and should be preserved for reference, when the memory requires assistance, which will occasionally be the case, when the machine has not been used for some length of time. (p. 13) The topics covered in the three sections are more or less redundant (each covering some aspect of the basic functions of the machine; see Table 2), but different purposes affect both presentation and exact content. Tension, for example, is discussed in all three sections. In the vignette, tension is discussed and its adjustment explained in the context of solving a problem (it is one possible reason why the thread breaks when Mr. Aston begins to sew [p. 4]). The “machine” directions (as well as the “sewing” directions) are intended for reference and structured somewhat differently. Toward this end, in the “Directions for Using the Family Sewing Machine,” we find tension discussed in two single-topic paragraphs. These topics are presented without added contextual information. In the “Directions for Sewing,” the technique for adjusting tension is again described, but this time in the context of thread choice and fabric type (p. 9). In this extended discussion, we learn that there is generally no need to adjust tension even with different sizes of thread, but that wool fabrics require a tighter than usual tension, and that silk threads can tolerate much greater tension than cotton. Similarly, the directions for sewing address the many different types of sewing a woman might do: hemming, felling, gathering, tucking, quilting, and embroidering (pp. 11–12). Yet another section, “The Relative Merits of the Sewing Machine Stitches,” likewise makes reference to the larger context of women’s sewing, with discussion of the durability of the different seams through successive washings and ironings. Finally, through the testimonials at the end of the document, we learn that by choosing a Grover and Baker sewing machine, a woman joins the company of ladies as opposed to “tailors and others” (p. 19) who prefer shuttle machines. The respected social status of that company is indicated by the quality and celebrity of those happy users in a list (pp. 27–28) that includes the wives or daughters of noted ministers (such as Henry Ward Beecher), politicians (including James Pollack, ex- APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals Durack TABLE 2: TOPICS IN SUCCESSIVE SECTIONS OF THE GROVER AND BAKER MANUAL “A Home Scene” “Directions for Using the Family Sewing Machine” “How to Prepare for Work, and Directions for Sewing” Operating the treadle Placing the upper spool Threads or silk Feeding fabric through the machine The under spool Tension Adjusting thread tension The vertical needle must be set Needles Setting the vertical needle To thread the vertical needle To regulate the length of the stitch Threading the machine To thread the circular needle To commence sewing Threading the circular needle To commence sewing Selvedges or overhand seams Removing work from the machine To regulate the length of the stitch To hem without the hemmer Removing a seam The tension upon the threads To adjust the Hemming-Gauge Oiling the machine The tension is regulated To hem with the hemmer To detach the cloth To fell When the machine is much used To gather The belt of the balance wheel To tuck To quilt To embroider To cross a seam To turn a corner To take the work out Governor of Pennsylvania), and the editors of the New York independent, the New York Christian advocate, the Home journal, the Brooklyn star, and the Jeffersonian. AUTHORITY AND SEXISM IN 19th-CENTURY SEWING MACHINE DOCUMENTATION In the preceding analysis, I have described how each of these very different documents responded to the needs of an audience comprised primarily of women. Now I will reconsider these documents in light of the question posed at the beginning of the article, whether it is possible for technical writing to be nonsexist in a world where technol- ogies are allocated for use according to the sex of the user. Of the two manuals, that published for the Singer sewing machine is more tightly focused on the knowledge and concerns of the 19th-century masculine sphere. It relies on a vocabulary more suited to the machine shop than to the sewing circle, and admires only the beauty of the invention itself rather than of the products it can produce or the stitch that it makes. It usurps female authority and denies by omission that women have valuable knowledge that they bring to the task at hand. This text ignores the larger question of applying the technology to the context of its use (the household) and to the Second Quarter 1998 • TechnicalCOMMUNICATION 191 APPLIED RESEARCH Durack Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals . . . this document clearly reinforces social hierarchies pertaining to masculine and feminine behavior and technological expertise. her patience in teaching him, attributing her success to the machine’s simplicity: I am more than convinced of its simplicity, and think, with a large majority of people, that the Grover and Baker is the best made and most easily managed machine, for family use, that can be purchased. (p. 6) If a woman should have difficulty in learning to use the machine, we are to understand that tasks (household linens and clothing) for which women would use the machine. The document seeks not to establish rapport with the reader, but rather dictates the terms and conditions of use. When problems occur, they do so because of the failure of the operator: “If at any time the Machine appears to run too hard, it may be presumed that some part which requires oiling has not been oiled”; “A strict observance of this rule will save the breaking of many needles” (p. 3). The voice of authority is that of the male machinist or inventor. The manual is sexist in the manner described by Treichler in its valuing of the “public over the private sphere” (such the machine’s economic versus personal/social value to the user) and its use of words that represent the “activities, interests, and concerns, associated primarily with men” (p. 53). But what of the Grover and Baker manual? This document is more clearly tuned in to the real needs and knowledge of the women users of the machine. In this small booklet, women are granted authority in at least two senses: through the implied female identity of the writer and by reference to and acknowledgment of women’s expertise in sewing. Women are also granted technological authority, demonstrated in “A Home Scene” by the analytical, problem-solving capabilities modeled by Mrs. Aston in contrast to her husband’s apparent incompetence. Yet even this document clearly reinforces social hierarchies pertaining to masculine and feminine behavior and technological expertise. Mr. Aston, it turns out, is not truly inept but is instead testing his wife; after she has guided him through solutions to numerous problems, he “confesses”: . . . I was incredulous that you had so good a knowledge of the machine, and to test it, felt desirous of seeing how far you could help me out of any difficulty I could get into. (p. 6) The whole thing has been a ruse. And, rather than congratulating her on acquiring expertise with a device so complex as the sewing machine (a fact established by the need for and existence of the patent pool), he admires instead 192 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 There is nothing in [the sewing machine’s] management that the simplest mind may not grasp. . . . Much depends on the natural capacity of the learner; but there is no person of ordinary intelligence who cannot become an expert operator by the exercise of a very little patience. (p. 13) If a woman has difficulty learning, any deficiency lies with her and not with the complexity (nor the temperamental nature) of the machine. Finally, in a reminder that it is Mr. Aston’s first evening with the sewing machine that we have been invited to observe (through the subtitle of the story), Mary’s pleasure with the device is interpreted through Mr. Aston’s eyes and valued for its effect on him. Aston congratulates himself thus: I feel that I have made a capital investment for saving time and labor, and gained with the Sewing Machine an assortment of sweet smiles, pleased and contented looks; and many pleasant evenings we will have on account of the freedom which the Sewing Machine will give you, Mary. (p. 6) Such statements grant priority to the machine’s value in economic terms, and of its rewards as enjoyed by the master of the house. Rather than granting Mary access to “masculine” attributes such as mechanical skill and analytical ability, the machine is “feminized” and characterized as simple enough for even a woman to use. The author includes herself as a seamstress, respectfully acknowledges the conventional method, then tactfully suggests a newer technique. APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals The documents I have analyzed are historic examples of two very different approaches to technical communication. CONTEMPORARY IMPLICATIONS: SEXIST, GENDER-NEUTRAL, AND NONSEXIST TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION The documents I have analyzed are historic examples of two very different approaches to technical communication. The Grover and Baker manual is rich with context and examples, even to the extent of providing a narrative which details the machine’s functions as well as its social and physical placement within the household. This narrative, like the case studies Stewart (1991) discusses, plays an important role: in addition to illustrating content and involving the reader, it also “socializ[es] the neophyte” to the machine (p. 122). In doing so, it defines a then-new relationship between 19th-century women and machines, establishing the acceptability of mechanical expertise in women so long as that skill is circumscribed in support of women’s traditional tasks and domestic roles and such expertise does not challenge the socially sanctioned view of greater mechanical skill in men. Because it is explicit in its description of the sex-differentiated relationships between men, women, and the sewing machine, it presents, from a 20th-century vantage point, an easy example of sexism in technical writing. In contrast, we might admire the Singer leaflet, for all its apparent deficiencies, as a good example of genderneutral technical communication: writing that employs surface-level features that are not marked for gender (such as a preference for sewing machine operator over seamstress). After all, the only explicit indication that sewing machine users might be defined by sex appears in the illustration of a woman seated at the machine on the front of the leaflet. Otherwise, an impersonal tone, imperative style, and the use of nouns and pronouns that are not gender-marked (“operator,” “you”) would seem to equitably accommodate use of the machine by either men or women. I’ve sought to demonstrate, however, that this document can also be considered sexist, because of the masculine authority it invokes and its denial of feminine expertise. As Sauer (1993) has demonstrated, a text’s form can serve to silence women’s voices and women’s priorities in preference for the priorities of companies. In presenting procedures outside of their larger context and application, sewing machine manufacturers dismissed the knowledge and traditions of their audience, simultaneously denying Durack the complexity of the early machines and the value of a woman’s knowledge and skill. Women’s interests and responsibilities were not overlooked by manufacturers but were divorced from machine documentation, in essence reflecting and reinforcing the interests of separate spheres by separate publications: scenarios such as the “Home Scene” disappeared from manuals, which “objectively” reflected a masculine world of machines. Other publications distributed by the sewing machine companies— children’s booklets, poetry, short stories, condensed versions of Shakespeare’s works, and patterns for fancy work and garments—reflect a feminine world concerned with relationships and care for others. These separate genres reinforce 19th-century ideals of women’s silence when in the company of men (Spender 1983) by eliminating women’s authority in the context of machine sewing. Relating the machine to the practices and concerns of the private sphere were the women employed by the manufacturers to demonstrate the machines and to provide instruction to purchasers. In this fashion, women’s special knowledge of and strategies for sewing by machine were consigned to oral circulation, one of many means by which a literate patriarchal society subtly silences the voices of women in histories of technology and technical communication. Today, it seems we face something of a catch-22 whenever we are tasked with shaping communications for technologies targeted for use by populations defined by sex. If we provide social and contextual cues (situated examples, scenarios, and cases), we may make it easier for users to put new technologies to work, but we also explicitly participate in socializing users into roles and relationships with technology that may collaborate in reproducing the existing social order. Crafting instructions with gender-neutral surface features may be a step in the right direction in terms a feminist agenda, but such a tactic fails to guarantee that sexism in our writing is eliminated. As Frank and Treichler (1989) point out, nonsexist language is language with a political agenda: it “works against sexism in society. While many Today, it seems we face something of a catch-22 whenever we are tasked with shaping communications for technologies targeted for use by populations defined by sex. Second Quarter 1998 • TechnicalCOMMUNICATION 193 APPLIED RESEARCH Durack Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals gender-neutral terms are consistent with nonsexist usage, the two are not the same” (p. 18). Nonsexist language takes many forms—including a purposeful yet unexpected pairing of nouns and pronouns such as “home sewing” and “he”—and actively challenges sexism in society. In doing so, it may draw attention to the text and away from the task at hand. Is it possible to eliminate sexism from technical writing when the technology in question is associated by its use to men or to women? Cockburn and Ormrod (1993) assert that “technology relations are . . . inevitably, gender relations” (p. 155). With any technology, they continue, An identity is projected for the artifact by its positioning in the store and also by advertising, point-of-sale material, instruction booklets, the way it is spoken about, the sales pitch . . . . Gender is unavoidably at work in the whole life trajectory of a technology. (Emphasis added; p. 156) A writer—any writer, regardless of personal politics— can move only so far in the direction of change as long as the technologies we write about are gender-bound in their inception, production, and use, and men and women are defined in contrast to one another, as opposites. Try as we may (and wish as we might), eradicating sexism from technical writing is only possible to the extent that gender does not serve in our culture as a primary vehicle for demarcating its citizens, their capabilities, and the tools they use for work. TC ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express special thanks to the many professionals at the Smithsonian Institution who have helped in many ways with this research: Shelly Foote of the Costume Division, National Museum of American History, who kindly examined the clothing styles on the early sewing machine manuals to help determine approximate publication dates; Scott Schwartz, Susan Strange, and Wendy Shay of the Archives Center for helping me obtain complete copies of some of these documents; and Catherine Keen and Annie Kuebler (also of the Archives Center) and David C. Burgevin (of the Office of Photographic Services) who helped provide the photographs accompanying this article. The materials examined in this article were originally identified during a visit to the Smithsonian funded by an STC research grant; I am grateful to the Society for Technical Communication for its support. Thanks also to Dr. Stephen A. Bernhardt and to the anonymous reviewers and review coordinator of this manuscript for their helpful suggestions for revision. REFERENCES Allen, J. 1991. “Gender issues in technical communication studies: An overview of the implications for the profession, 194 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 research, and pedagogy.” Journal of business and technical communication 5:371–392. Baron, A., and S. E. Klepp. 1984. “‘If I didn’t have my sewing machine . . .’: Women and sewing machine technology.” In A needle, a bobbin, a strike: Women needleworkers in America, edited by J. M. Jensen and S. Davidson. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, pp. 20 –59. Beecher, C. E., and H. B. Stowe. [1869] 1975. The American woman’s home; Or principles of domestic science. Reprint. Hartford, CN: Stowe-Day Foundation. Bernhardt, S. A. 1992. “The design of sexism: The case of an army maintenance manual.” IEEE transactions on professional communication 35:217–221. Bourne, F. G. 1895. “American sewing machines.” In One hundred years of american commerce, Vol. 2., edited by C. M. Depew. New York, NY: D. O. Hains, pp. 525–539. Brandon, R. 1977. A capitalist romance: Singer and the sewing machine. Philadelphia, PA: J. B. Lippincott Company. Brockmann, R. J. 1986. Writing better computer user documentation: From paper to online. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. Carroll, J. M., P. L. Smith-Kerker, J. R. Ford, and S. A. MazurRimetz. 1987. -88. “The minimal manual.” Human-computer interaction 3, no. 2: 123–153. Cockburn, C. 1988. Machinery of dominance: Women, men, and technical know-how. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press. Cockburn, C. and S. Ormrod. 1993. Gender and technology in the making. London, England: Sage Publications. Cooper, G. R. 1976. The sewing machine: Its invention and development. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. Cowan, R. S. 1983. More work for mother: The ironies of household technology from the open hearth to the microwave. New York, NY: Basic Books. Dell, S. A. 1989. “Promoting equality of the sexes through technical writing.” Technical communication 36:248 –251. Directions for using Singer’s patent straight-needle, transverse shuttle sewing machines. Circa 1859 – 60. Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. APPLIED RESEARCH Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals Dobrin, D. 1983. “What’s technical about technical writing.” In New essays in technical and scientific communication: Research, theory, practice, edited by P. V. Anderson, R. J. Brockmann, and C. R. Miller. Farmingdale, NY: Baywood Publishing Company, Inc., pp. 227–50. Dobrin, D. 1989. “Know your audience.” Writing and technique. Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, pp. 93– 109. Duin, A. H. 1989. “Factors that influence how readers learn from text: Guidelines for structuring technical documents.” Technical communication 36:97–101. Duin, A. H. 1988. “How people read: Implications for writers.” Technical writing teacher 15.3:185–193. Duin, A. H., and C. J. Hansen, eds. 1996. Nonacademic writing: Social theory and technology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Flower, L., J. R. Hayes, and H. Swarts. 1983. “Revising functional documents: The scenario principle.” In New essays in technical and scientific communication: Research, theory, practice, edited by P. V. Anderson, R. J. Brockmann, and C. R. Miller. Farmingdale, NY: Baywood Publishing Company, Inc., pp. 41–58. Durack and C. R. Miller. Farmingdale, NY: Baywood Publishing Company, Inc., pp. 90 –108. Keller-Cohen, D. 1987. “Organizational contexts and texts: The redesign of the Midwest Bell telephone bill.” Discourse Processes 10:417– 428. Kessler-Harris, A. 1982. Out to work: A history of wage-earning women in the United States. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Kidwell, Claudia. 1979. Cutting a fashionable fit: Dressmakers’ drafting systems in the United States. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. Kramarae, C. 1988a. “Talk of sewing circles and sweatshops.” In Technology and women’s voices: Keeping in touch, edited by C. Kramarae. New York, NY: Routledge and Kegan Paul, pp. 147–160. Kramarae, C., ed. 1988b. Technology and women’s voices: Keeping in touch. New York, NY: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Lay, M. M. 1994. “The value of gender studies to professional communication research.” Journal of business and technical communication 8, no. 1:58 –90. Frank, F. W., and P. A. Treichler, eds. 1989. Language, gender, and professional writing. New York, NY: Modern Language Association. Mackin, J. 1989. “Surmounting the barrier between Japanese and English technical documents.” Technical communication 36:346 –351. Herndl, C. G. 1991. “Understanding failures in organizational discourse: The accident at Three Mile Island and the shuttle Challenger disaster.” In Textual dynamics of the professions: Historical and contemporary studies of writing in professional communities, edited by C. Bazerman and J. Paradis. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 279 –305. Matchett, M., and M. L. Ray. 1989. “Revising IRS publications: A case study.” Technical communication 36:332–340. A home scene; or Mr. Aston’s first evening with Grover and Baker’s celebrated family sewing machine, containing directions for using, and a discussion of the relative merits of stitches. 1859. NY, NY: T. Holman. Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Mirel, B., S. Feinberg, and L. Allmendinger. 1991. “Designing manuals for active learning styles.” Technical communication 38:75– 88. Hounshell, D. A. 1984. From the American system to mass production, 1800 –1932: The development of manufacturing technology in the United States. Baltimore, MD and London, England: The Johns Hopkins University Press. Huckin, T. N. 1983. “A cognitive approach to readability.” In New essays in technical and scientific communication: Research, theory, practice, edited by P. V. Anderson, R. J. Brockmann, Matsui, K. 1989. “Document design from a Japanese perspective: Improving relationships between clients and writers.” Technical communication 36:341–345. “The modern seamstress.” 1869. Willcox and Gibbs silent family sewing machine. New York, NY: Sanford, Cushing and Co. Printers. Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Norman, D. A. 1990. The design of everyday things. New York, NY: Doubleday. Norris, J. D. 1990. Advertising and the transformation of American society, 1865–1920. Contributions in economics and economic history 110. New York, NY: Greenwood Press. Second Quarter 1998 • TechnicalCOMMUNICATION 195 APPLIED RESEARCH Durack Sexism in 19th-century Sewing Machine Manuals Parton, J. Circa 1872. History of the sewing machine. New Haven, CT: Howe Machine Company. First published in Atlantic Monthly, May 1867. Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Postman, N. 1993. Technopoly: The surrender of culture to technology. 1992. New York, NY: Vintage Books. Quiepo, L. 1991. “Taking the mysticism out of usability test objectives.” Technical communication 38:185–189. Redish, J. C., R. M. Battison, and E. S. Gold. 1985. “Making information accessible to readers.” In Writing in nonacademic settings, edited by L. Odell and D. Goswami. New York, NY: The Guilford Press, pp. 129 –153. Rubens, P. M. 1986. “A reader’s view of text and graphics: Implications for transactional text.” Journal of technical writing and communication 16:73– 86. Sauer, B. A. 1993. “Sense and sensibility in technical documentation: How feminist interpretation strategies can save lives in the nation’s mines.” Journal of business and technical communication 7, no. 1:63– 83. Schneir, M., ed. 1972. , 1994. Feminism: The essential historical writings. New York, NY: Random House. Reprinted New York, NY: Vintage Books. 196 TechnicalCOMMUNICATION • Second Quarter 1998 Schriver, K. A. 1989. “Document design from 1980 to 1989: Challenges that remain.” Technical communication 36:316 – 331. Schriver, K. A. 1997. Dynamics in document design. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. Spender, D. 1983. Women of ideas and what men have done to them: From Aphra Behn to Adrienne Rich. London, England: AR Paperbacks. Stewart, A. H. 1991. “The role of narrative structure in the transfer of ideas: The case study and management theory.” In Textual dynamics of the professions: Historical and contemporary studies of writing in professional communities, ed. Charles Bazerman and James Paradis. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 120 –144. Strasser, S. 1982. Never done: A history of American housework. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. Treichler, P. A. 1989. “From discourse to dictionary: How sexist meanings are authorized.” In Language, gender, and professional writing, eds. Francine Wattman Frank and Paula A. Treichler. New York, NY: Modern Language Association, pp. 51–79. Wajcman, J. 1991. Feminism confronts technology. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press.