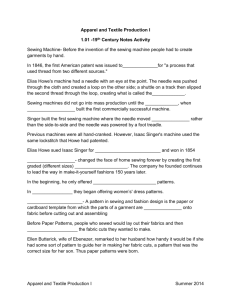

a stitch in time: the rise and fall of the sewing machine patent thicket

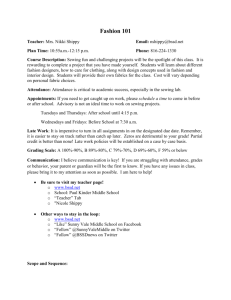

advertisement