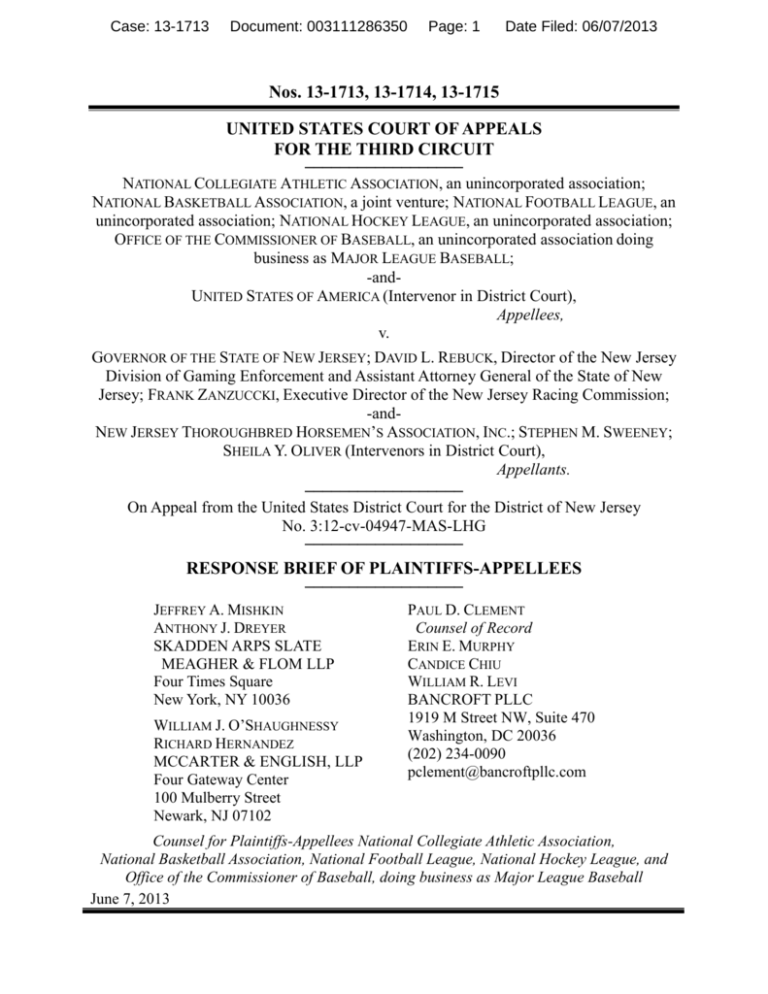

Response Brief - The Sports Esquires

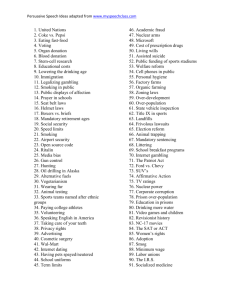

advertisement