04-2014

advertisement

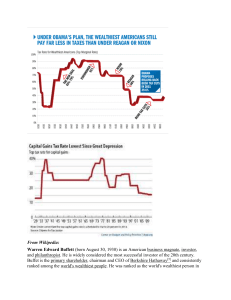

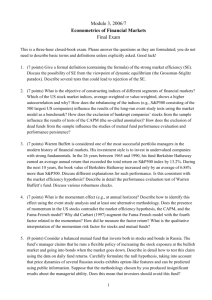

April 10, 2014 Dear Client, “Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose” Although it was French Novelist Alphonse Karr who wrote this phrase, it was in one of my Benjamin Graham readings where I came across the phrase. These words, in English mean, “The more things change, the more they are the same.” These simple words ring so true, and to me, are very powerful. Thinking about Karr’s words brings to mind several important lessons that I have learned from both great teachers and mentors and its applicability to investing. Yes, things change, but in many ways, not really. So many investment advisors try to make their investing so mysterious. They make it more complicated than it needs to be, or in some cases, they come up with some gimmick to wow prospective clients. When I was studying at the Doctoral Level, as a Visiting Scholar at UCLA, under Professors Moshe Rubinstein and Robert Andrews, I wrote Warren Buffett a letter, asking him if I could come to Omaha and see him to discuss investing methods, but specifically, Graham’s methods. He wrote a polite letter back, telling me “no” and that “Graham’s methods are clear and lucid.” Later, I did meet with the Oracle through the courtesy of John Anderson, the benefactor of the Anderson Graduate School of Management at UCLA, and we had a nice talk about Graham. What I learned from Mr. Buffett is this: investors, especially investment advisors, like to complicate things. He went on to tell me that it might be because of the intellectual challenge in trying to reinvent the wheel. There is a great Buffett story about him and his three pals going out to lunch in New York. They find a diner, and in Buffett style, he orders a ham sandwich and a Coke. The next day, the same three go out to lunch and try to decide where they want to go. Buffett says, “Let’s go to the diner where we ate yesterday.” One of his friends asked him, “Don’t you want to try something different?” Buffett replies, “Why take the risk? We already know this place.” Buffett applies this same idea to stocks and investments. If you analyze a company and you have spent some time learning about it and then owning it, why should you sell it? Do you sell because you think the stock price has topped out? Do you sell it because you think you like something else better? Do you sell it because some talking head on CNBC said so, or you read some newsletter that advocates selling it? Graham said, “You sell a stock when the operations of a company is severely impacted and that it is not temporary, or if the stock is grossly overvalued.” Phillip Fisher, another investment great, said “The time to sell a stock, if correctly chosen, is almost never.” Lately, the talking heads have asked the question, has Buffett lost his touch? Jim Cramer said, “Don’t bet against the Oracle.” I’m no big fan of Cramer, but the guy is super smart, and in my eyes, when he defended Buffett’s track record, I began to change my tune about him. Cramer, who is a trader, says that between the lines, Buffett’s simplistic approach has merit, even if it is in contrast to his approach. In the past, when Buffett faltered, people wrote him off as a has-been. Of course, that was in 1998, right before the tech crash of 2000. Buffett’s track record and reputation were restored shortly thereafter. Now, with Buffett being trashed again and the high-flying stocks such as LinkedIn, Facebook, and Twitter being thrashed, is this a sign of a major correction? Graham advocated a simple division of stocks and bonds in a diversified portfolio – a portfolio that stands the test of time. We don’t know with certainty what lies around the corner. We can’t see with a crystal ball. Professor Rubinstein taught me that concept and went on to explain to me that the only thing that is certain is uncertainty. Otherwise, everyone would be rich. That’s where diversification pays off. This is the major reason why we still have bonds in our portfolios and why we don’t have 100% stocks. Yes, at the current time, there is more risk in bonds than in stocks, but we don’t know with certainty that some event will reverse those odds. Bonds have a place in our portfolios, and I am willing to sacrifice some performance for a margin of safety. Over the long term, our track record speaks for itself. Sue Dopson, the Rhodes Trust Professor at Saïd Business School and my home college, Green-Templeton at Oxford University, told me to simplify the research methodology for my dissertation on Forest Investments. She said that the dissertation was too complicated and would be much better and understandable if I could put it in a simple manner. I thought that was a bit odd when a professor from one of the greatest universities in the world asked me to simplify my dissertation written at the doctoral level. Only later when I was in front of the examining board to defend my dissertation and one of the members told me that “we are here to have simple conversation with you so we can understand your important work” was I able to understand what she meant. The late professor, Marty Marshall of the Harvard Business School, also believed in simplicity. I loved him with all of my heart and soul because behind that gruff exterior, he preached the gospel of simplicity. He was a marketing professor and was also well paid as a consultant to companies like Coca Cola, AT&T, and other big corporations. Yet, instead of inventing the newest strategic model, he believed in simple research, which he coined “mother-in-law research.” What Marty meant by that term was instead of relying on fancy market research or complex goobly-gook, go and see for yourself what is going on. Marty was another advocate of simplicity. Now, does that mean you can buy a security without understanding the company and its financial data? No, you can’t skip these steps. Understanding this is critical and I spend the majority of my time doing just this. Benjamin Graham was a big advocate of fundamental analysis, which examines in detail a company’s operation, and that’s what we practice. For example, Coca Cola and Pepsi sales in the U.S. are declining. That affects operations, doesn’t it? However, in the case of Coca Cola, their international sales are growing, and in Pepsi’s case, it is Frito-Lay that is the crown jewel. No, we shouldn’t sell either one. Should we take into consideration some economic fundamentals? Yes, we should, but the proportion between fundamental analysis and economics should be approximately at what Peter Lynch advocated: 85% stock picking and 15% economics. We do engage in reading and understanding macroeconomics through our research collaborations with BCA Research of Montreal and the University of Oxford. We need to understand the global dynamics that affect our portfolios, but we are not obsessed with it. We do sell stocks from time to time, but our portfolio turnover is considered to be low. I feel if I have chosen the stock for the right reasons and the operations of the company have not changed, then why trigger capital gains and have to search for another one. Sort of like Buffett’s ham sandwich. So when I hear my colleagues tell their prospective clients they are all-knowing because they uncover socalled anomalies or discrepancies, or they are experts in forensic accounting, I shudder and think why they don’t keep it simple. We know of an investment advisor who defrauded his clients after telling them he was a forensic accountant. That didn’t keep him from wiping them out with poor stock selections. Last week, as many of you have heard, Michael Lewis was on 60 Minutes, and he stated that he thought the market was rigged because of flash trading. Of course, this was good publicity for his newly released book. I suppose in the very short run that flash trading is not good, but if you are long-term investor such as Buffett or myself, then it shouldn’t matter. Flash trading affects only day traders, large institutions, and other traders. As Alphonse Karr famously stated, “the more that things change, the more they are the same” is so true because flash trading is nothing more than an updated version of program trading that has been around for more 25 years. I do think it should be banned for the sake of market stability, but in the long run, it doesn’t affect me and you. Since I had told you we would be moving to Charles Schwab sometime this spring, I have had a change of mind. I have been in discussions with Fidelity about our move and they provided me with everything I need to make an intelligent decision about their stability and safety. They have also agreed to provide us support in terms of paying for part of our research and underwriting some of our client events. More importantly, they have agreed to lower the commissions that you pay directly to them. Therefore, you won’t be receiving any paperwork in the mail as I mentioned previously, because we are staying at Fidelity. Thank you for your confidence in me. I enjoy working with each and every one of you. You have given me the opportunity to do what I enjoy most, pick stocks and work with my clients. With kind regards, Steve Yamshon Investment Counsel