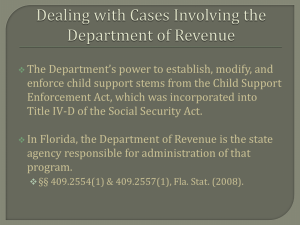

CONSTRUCTION LAW FOR ATTORNEYS IN FLORIDA SEMINAR

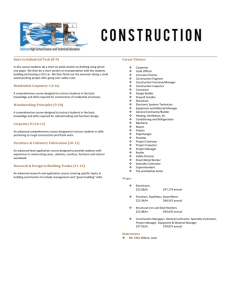

advertisement