POINT OF VIEW Stories are told through someone called a narrator

advertisement

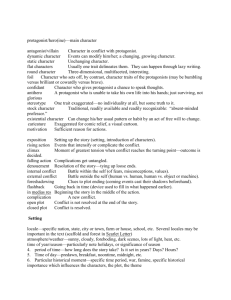

POINT OF VIEW i Stories are told through someone called a narrator. The narrator is different from the author, as confusing as that sounds. Since most of the action in fiction is made up in the author's mind, it is not possible for the author to be the person telling you what happened. So, the author picks a narrator who will describe the action, setting, etc., to you. There is usually only one point of view in a story, especially in short stories. It is very difficult to have several narrators trying to tell one story, although not impossible. However, it is not practical within a single story. There are three basic points of view: First person, Third person limited and Omniscient. First Person The first person narrator is a character in the story who tells the story. You can easily recognize this narrator because he must use the personal pronoun "I." The first person narrator is generally the protagonist in the story. This is a very limited point of view. When there is a first person narrator, the reader can only know what that characters sees, hears, and thinks. It is not possible to know what other characters in the story are doing unless they are within the sight or hearing of the narrator, nor is it possible to know what other characters are thinking. It is very important that the reader understand the this narrator is not the same person as the author. In non-fiction that would be the case. But in fiction, the two are completely separate. The benefit to this type of point of view is that the narrator can heighten suspense because he cannot tell the reader what is going on behind that closed door. This narrator can also make the reader feel more comfortable, more able to identify with him. One of the more interesting things about this type of narrator is that, realistically, the reader knows that the narrator will survive the story. It's just trying to discover how that makes the narration so interesting. Third Person Limited Exactly as it sounds, this narrator is limited in what he can tell you. The term "third person" tells you that the narrator is separate from the author. This narrator is not a character in the story. Rather, he is an observer outside of the influence of the story. Picture him as hovering above the action somewhere, following the protagonist around, unseen. Generally, the limited narrator only follows the protagonist through the story. Like the first person narrator, we usually do not know what the other characters are up to unless they are within sight or hearing of the protagonist. We might know the protagonist's thoughts, though not always. The benefits are many to this narrator. Suspense can increase because we only know what the protagonist knows. Our attention is not distracted by trying to follow several different characters through their lives within the confines of the story. We only have to worry about one or two. This is the most popular narrator used in fiction, probably because of the difficulty in tying all of the threads of several characters together. It is also a very effective type of narration. Omniscient The word "omniscient" means, literally, ''all-knowing." So, an omniscient narrator knows everything. He knows what every character is doing at any given moment. He knows what all of the characters are thinking. He knows the past, the present, and the future of every character. He is sometimes thought of as a god who is watching from above. This narration can often show the reader several different things that area happening at one time. The stereotypical "Meanwhile, back at the ranch" idea suggests an omniscient narrator. This narrator often makes judgments for us about the action or the characters. This narrator can be very effective in fiction. We know that the killer is behind that closed door but our poor protagonist does not. It heightens our sympathy for the protagonist and increases our mistrust of the antagonist. This is an excellent narrator to use for action-packed adventure stories. It is also easy to use. People often confuse the point of view with perspective. Point of view, remember, is the person who narrates the story. Perspective, on the other hand, simply keeps the reader focused on one character at a time. A first person narrator, for example is limited to a single perspective: his own. The limited narrator is also limited to that single perspective. The omniscient narrator is the one who can show the reader multiple perspectives of the events of the story, which he does by taking the reader into the minds of more than one character, by describing action that is separate from the other action but still related to it. :n is displayed in the development of the proiy that the protagonist experiences. But in e than one focal character, and the theme I b, .amining the different experiences of more trate the validity of this statement by examin:ters in one of die following: Snow" (page 86). • " (page 166). six-Bits" (page 564). Point of View •I Primitive storytellers, unbothered by considerations of form, simply spun their tales. "Once upon a time," they began, and proceeded to narrate the story to their listeners, describing the characters when necessary, telling what the characters thought and felt as well as what they did, and interjecting comments and ideas of their own. Modern fiction writers are artistically more self-conscious. They realize that there are - many ways of telling a story; they decide upon a method before they begin, or discover one while in the act of writing, and may even set up rules for themselves. Instead of telling the story themselves, they may let one of the characters tell it; they may tell it by means of letters or diaries; they may confine themselves to recording the thoughts of one of the characters. With the growth of artistic consciousness, the question of point of view—of who tells the story, and, therefore, of how it gets told—has assumed special importance. To determine the point of view of a story, we ask, "Who tells the story?" and "How much is this person allowed to know?" and, especially, "To what extent does the narrator look inside the characters and report their thoughts and feelings?" •S 1. Omniscient 2. Third-person limited 3. First person 4. Objective (a) Major character (b) Minor character (a) Major character (b) Minor character cnapter Nve / roint ot View Though many variations and combinations are possible, the basic points of view are four, as follows: 1. In the omniscient point of view, the story is told in the third person by a narrator whose knowledge and prerogatives are unlimited. Such narrators are free to go wherever they wish, to peer inside the minds and hearts of characters at will and tell us what they are thinking or feeling. These narrators can interpret behavior and can comment, if they wish, on the significance of their stories. They know all. They can tell us as much or as little as they please. The following version of Aesop's fable "The Ant and the Grasshopper" is told from the omniscient point of view. Notice that in it we are told not only what both characters do and say, but also what they think and feel; notice also that the narrator comments at the end on the significance of the story. (The phrases in which the narrator enters into the thoughts or feelings of the ant and the grasshopper have been italicized; the comment by the author is printed in small capitals.) Weary in every limb, the ant tugged over the snow a piece of corn he had stored up last summer. It would taste mighty good at dinner tonight. A grasshopper, cold and hungry, looked on. Finally he could bear it no longer. "Please, friend ant, may I have a bite of corn?" "What were you doing all last summer?" asked the ant. He looked the grasshopper up and down. He knew its kind. "I sang from dawn till dark," replied the grasshopper, happily unaware of what was coming next. "Well," said the ant, hardly bothering to conceal his contempt, "since you sang all summer, you can dance all winter." HE WHO IDLES WHEN HE'S YOUNG WILL HAVE NOTHING WHEN HE'S OLD Stories told from the omniscient point of view may vary widely in the amount of omniscience the narrator is allowed. In "Hunters in the Snow," we are frequently allowed into the mind of Tub, but near the end of the story the omniscient narrator takes over and gives us information none of the characters could know. In "The Destructors," though we are taken into the minds of Blackie, Mike, the gang as a group, Old Misery, and the lorry driver, we are not taken into the mind of Trevor—the most important character. In "The Most Dangerous Game," we are confined to the thoughts and feelings of Rainsford, except for the brief passage between Rainsford's leap into the sea and his waking in Zaroff 's bed, during • which the point of view shifts to General Zaroff. Chapter Five / Point of View 229 The omniscient is the most flexible point of view and permits the widest scope. It is also the most subject to abuse. It offers constant danger that the narrator may come between the readers and the story, or that the continual shifting of viewpoint from character to character may cause a breakdown in coherence or unity. Used skillfully, it enables 'the author to achieve simultaneous breadth and depth. Unskillfully used, it can destroy the illusion of reality that the story attempts to create. 2. In the third-person limited point of view, the story is told in the third person, but from the viewpoint of one character in the story. Such point'of-view characters are filters through whose eyes and minds writers look at the events. Authors employing this perspective may move both inside and outside these characters but never leave their sides. They tell us what these characters see and hear and what they think and feel; they possibly interpret the characters' thoughts and behavior. They know everything about their point-of-view characters—often more than the characters know about themselves. But they limit themselves to these characters' perceptions and show no direct knowledge of what other characters are thinking or feeling or doing, except for what the point-of-view character knows or can infer about them. The chosen character may be either a major or a minor character, a participant or an observer, and this choice also will be a very important one for the story. "Interpreter of Maladies," "Miss Brill," and "A Worn Path" are told from the third-person limited point of view, from the perspective of the main character. The use of this viewpoint with a minor character is rare in the short story, and is not illustrated in this book. Here is "The Ant and the Grasshopper" told, in the third person, from the point of view of the ant. Notice that this time we are told nothing of what the grasshopper thinks or feels. We see and hear and know of him only what the ant sees and hears and knows. Weary in every limb, the ant tugged over the snow a piece of corn he had stored up last summer. It would taste mighty good at dinner tonight. It was then that he noticed the grasshopper, looking cold and pinched. "Please, friend ant, may I have a bite of your com?" asked the grasshopper. He looked the grasshopper up and down. "What were you doing all last summer?" he asked. He knew its kind. "I sang from dawn till dark," replied the grasshopper. "Well," said the ant, hardly bothering to conceal his contempt, "since you sang all summer, you can dance all winter." Chapter Five / Point of View The third-person limited point of view, since it acquaints us with the world through the mind and senses of only one character, approximates more closely than the omniscient the conditions of real life; it also offers a ready-made unifying element, since all details of the story are the experience of one character. And it affords an additional device of characterization, since what a point-of-view character does or does ' not find noteworthy, and the inferences that such a character draws about other characters' actions and motives, may reveal biases or limitations in the observer. At the same time it offers a limited field of observation, for the readers can go nowhere except where the chosen character goes, and there may be difficulty in having the character naturally cognizant of all important events. Clumsy writers will constantly have the focal character listening at keyholes, accidentally overhearing important conversations, or coincidentally being present when important events occur. A variant of third-person limited point of view, illustrated in this chapter by Porter's "The Jilting of Granny Weatherall," is called stream of consciousness. Stream of consciousness presents the apparently random thoughts going through a character's head within a certain period of time, mingling memory and present experiences, and employing transitional links that are psychological rather than strictly logical. (Firstperson narrators might also tell their stories through stream of consciousness, though first-person use of this technique is relatively rare.) 3. In the first-person point of view, the author disappears into one of the characters, who tells the story in the first person. This character, again, may be either a major or a minor character, protagonist or observer, and it will make considerable difference whether the protagonist tells the story or someone else tells it. In "How I Met My Husband" and "The Lesson," the protagonist tells the story in the first person. In "A Rose for Emily," presented in Part 4, the story is told in the unusual first-person plural, from the vantage point of the townspeople observing Emily's life through the years. Our fable is retold below in the first person from the point of view of the grasshopper. (The whole story is italicized because it all comes out of the grasshopper's mind.) Cold and hungry, 1 watched the ant tugging over the snow a piece of corn he had stored up last summer. My feelers twitched, and I was conscious of a tic in my left hind leg. Finally I could bear it no longer. "Please, friend ant," 1 asked, "may I have a bite of your com?" He looked me up and down. "What were you doing all last sum' • mer?" he asked, rather too smugly it seemed to me. Chapter Five / Point o( 231 "I sang from dawn till dark," I said innocently, remembering the happy times. "Well," he said, with a priggish sneer, "since you sang all summer, you can dance all winter." t f**1 I '' The first-person point of view shares the virtues and limitations of the third-person limited. It offers, sometimes, a gain in immediacy and reality, since we get the story directly from a participant, the author as intermediary being eliminated. It offers no opportunity, however, for direct interpretation by the author, and there is constant danger that narrators may be made to transcend their own sensitivity, their knowledge, or their powers of language in telling a story. Talented authors, however, can make tremendous literary capital out of the very limitations of their narrators. The first-person point of view offers excellent opportunities for dramatic irony and for studies in limited or blunted human perceptiveness. In "How I Met My Husband," for instance, there is an increasingly clear difference between what the narrator perceives and what the reader perceives as the story proceeds. Even though Edie is clearly narrating her story from the vantage point of maturity— ultimately we know this from the ending and from the title itself—she rarely allows her mature voice to intrude or to make judgments on Edie's thoughts and feelings as a fifteen-year-old girl infatuated with a handsome pilot. The story gains in emotional power because of the poignancy of youthful romanticism that Edie's hopes and wishes represent, and because of the inevitable disillusionment she must suffer. By choosing this point of view, Munro offers an interpretation of the material indirectly, through her dramatization of Edie's experiences. In other stories, like "A Rose for Emily," the author intends the firstperson viewpoint to suggest a conventional set of perceptions and attitudes, perhaps including those of the author and the reader. Identifications of a narrator's attitudes with the author's, however, must always be undertaken with extreme caution; they are justified only if the total material of the story supports them, or if outside evidence (for example, a statement by the author) supports such an identification. In "A Rose for Emily" the narrative detachment does reflect the author's own; nevertheless, much of the interest of the story arises from the limited viewpoint of the townspeople and the cloak of mystery surrounding Emily and her life inside the house. 4. In the objective point of view, the narrator disappears into a kind of roving sound camera. This camera can go anywhere but can record only what is seen and heard. It cannot comment, interpret, or enter a character's mind. With this point of view (sometimes called also 232 ter Five/Point of View the dramatic point of view) readers are placed in the position of spectators at a movie or play. They see what the characters do and hear what they say but must infer what they think or feel and what they are like. Authors are not there to explain. The purest example of a story - told from the objective point of view would be one written entirely in dialogue, for as soon as authors add words of their own, they begin to interpret through their very choice of words. Actually, few stories using this point of view are antiseptically pure, for the limitations it imposes on the author are severe. Shirley Jackson's "The Lottery," presented in this chapter/is essentially objective in its narration. The following version of "The Ant and the Grasshopper" is also told from the objective point of view. (Since we are nowhere taken into the thoughts or feelings of the characters, none of this version is printed in italics.) The ant tugged over the snow a piece of corn he had stored up last summer, perspiring in spite of the cold. A grasshopper, his feelers twitching and with a tic in his left hind leg, looked on for some time. Finally he asked/ "Please, friend ant, may I have a bite of your corn?" The ant looked the grasshopper up and down. "What were you doing all last summer?" he snapped. "I sang from dawn till dark," replied the grasshopper, not changing his tone. "Well," said the ant, and a faint smile crept into his face, "since you sang all summer, you can dance all winter." The objective point of view requires readers to draw their own inferences. But it must rely heavily on external action and dialogue, and it offers no opportunities for direct interpretation by the author. Each of the points of view has its advantages, its limitations, and its peculiar uses. Ideally the choice of the author will depend upon the materials and the purpose of a story. Authors choose the point of view that enables them to present their particular materials most effectively in terms of their purposes. Writers of murder mysteries with suspense and thrills as the purpose will ordinarily avoid using the point of view of the murderer or the brilliant detective: otherwise they would have to reveal at the beginning the secrets they wish to conceal till the end. On the other hand, if they are interested in exploring criminal psychology, the murderer's point of view might be by far the most effective. In the Sherlock Holmes stories, A. Conan Doyle effectively uses the somewhat imperceptive Dr. Watson as his narrator, so that the reader may be kept in the dark as long as possible and then be as amazed as Wat- Chapter Five / Point of View /33 son is by Holmes's deductive powers. In Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment, however, the author is interested not in mystifying and surprising but in illuminating the moral and psychological operations of the human soul in the act of taking life; he therefore tells the story from the viewpoint of a sensitive and intelligent murderer. For readers, the examination of point of view may be important both for understanding and for evaluating the story. First, they should know whether the events of the story are being interpreted by a narrator or by one of the characters. If the latter, they must ask how this character's mind and personality affect the interpretation, whether the character is perceptive or imperceptive, and whether the interpretation can be accepted at face value or must be discounted because of ignorance, stupidity, or self-deception. Next, readers should ask whether the writer has chosen the point of view for maximum revelation of the material or for another reason. The author may choose the point of view mainly to conceal certain in' formation till the end of the story and thus maintain suspense and create surprise. The author may even deliberately mislead readers by presenting the events through a character who puts a false interpretation on them. Such a false interpretation may be justified if it leads eventually to more effective revelation of character and theme. If it is there merely to trick readers, it is obviously less justifiable. Finally, readers should ask whether the author has used the selected point of view fairly and consistently. Even in commercial fiction we have a right to demand fair treatment. If the person to whose thoughts and feelings we are admitted has pertinent information that is not revealed, we legitimately feel cheated. To have a chance to solve a murder mystery, we must know what the detective learns. A writer also should be consistent in the point of view; if it shifts, it should do so for a just artistic reason. Serious literary writers choose and use point of view so as to yield ultimately the greatest possible insight, either in fullness or in intensity. REVIEWING CHAPTER FIVE 1. 2. 3. 4. Explain how to determine the point of view in a story. Describe the characteristics of omniscient point of view. Review the definition of third-person limited point of view. Consider the virtues and limitations of first-person point of view. 5. Explore the use of objective point of view in Hemingway's "Hills Like White Elephants," presented in this chapter.