TEACHER

THE LAW

Inside...

Remember the Water Buffalo........................... 1

Book Review: David Nadvorney and Deborah

Zalesne, Teaching to Every Student:

Explicitly Integrating Skills and Theory

in the Contracts Class.................................. 3

Old Professor Tricks............................................. 4

The Supreme Court Conference Room:

Legal Writing as Legal Process.......................... 5

Infusing Ethics into the Legal Writing

Curriculum—and Beyond.............................. 7

Book Review: How Children Succeed:

Grit, Curiosity, and the Hidden Power of

Character............................................................ 8

It’s OK to Leave Law School............................. 10

Crossword Puzzle................................................ 11

Eliminating the Blackacre Opportunity Cost:

Using Real-World “Targeted Fact

Environments” in First-Year

LR&W Courses.................................................... 13

Reflection, Reality, and a Real Audience: Ideas

from the Clinic..................................................... 15

Beyond the Legal Classroom: Leveraging

Major Local Events to Engage Students and

Further an Interdisciplinary Approach to the

Study of Law................................................... 17

Teaching Statute Reading Basics in a First Year

Doctrinal Course: A Handout and Suggested

Classroom Exercises....................................... 18

Law School Communities “Saving Social

Security”— Imparting the Intangibles of

Practice Readiness.......................................... 21

Report from South Korea: My Experience

Teaching Law Students at Seoul National

University......................................................... 23

Passion is Necessary, Compassion is Priceless:

A Message to the Clinical Law Student..... 25

Introducing Students to Free On-line Legal

Research Resources: An Interactive Class..... 26

Happily Ever After: Providing Students With

Epilogues for Cautionary Tales................... 28

Developing Classroom Authenticity: “Big

Talk” Format.................................................... 29

Adding a Standardized Assessment Exercise to

the Legal Writing Toolbox............................ 31

On the Importance of Subtle Distinctions: A

Short Exercise in Close Reading and Critical

Thinking........................................................... 33

Blogging: Reflection Spurs

Students Forward........................................... 34

Classroom Justice: Beyond Paper-Chase

Pedagogy.......................................................... 35

Volume XIX, Number 2

SPRING 2013

Remember the Water Buffalo

By Katherine Silver Kelly

M

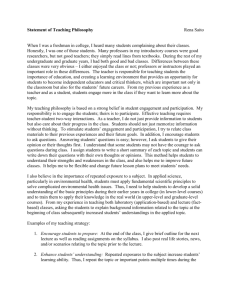

ost of us keep personal

mementos in our offices

and on our desks: a mug

emblazoned with our alma mater, a

plant or two, a photo of our spouse,

children, pets. These items serve several

purposes: they remind us why we

work and they also

provide a snapshot of

our personalities and

let others (students)

see that we are more

than just the professor

behind the podium.

As for my desk, right

next to the photo of

my husband stands a

photo of me — my 8th

grade school picture.

My family calls it the

“water buffalo picture,”

and for good reason. I

tried to straighten my very curly hair

and parted it down the middle. I look

like a water buffalo. Add a chipped front

tooth, out of control eyebrows and an

outfit that was meant to epitomize the

prepster I thought I was (it was the 80s,

so I refuse to take full responsibility)

and the resulting photo is pretty awful.

Eighth grade was not a good year for

me. I had a heightened sense of selfawareness thanks to the onset (or not)

of puberty, and I desperately wanted to

fit in. I thought I was the only one who

felt like this and wished I could be as

cool as everyone else. My mother told

me that things would get better and that

everyone was going through the same

thing. Although true, it did not make me

feel any better.

So, why do I keep such

an unflattering photo of

myself front and center

on my desk? Why would

I want to remind myself

of such an awkward,

confusing, and difficult

time in my life? Because

the student sitting across

from me might very well

be a water buffalo.

Law students are smart,

confident, and selfassured. And then they

start law school. Suddenly

everyone around you is a high achiever

and used to being the best and now

you are in competition with each other

for grades, jobs, leadership positions.

Rarely, if ever has a law student actually

failed at anything. In fact, most don’t

even consider failing (i.e., not being in

the top 10%) a possibility. When reality

hits, it can be very disconcerting and we

see lots of water buffaloes around exam

time and when grades are released.

— continued on page 2

THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013 | 1

SPRING 2013

Promoting the science

and art of teaching

The Law Teacher, Volume XIX,

Number 2

The Law Teacher is published twice a

year by the Institute for Law Teaching and

Learning. It provides a forum for ideas

to improve teaching and learning in law

schools and informs law teachers of the

activities of the Institute.

Opinions expressed in The Law Teacher

are those of the individual authors. They

are not necessarily the opinions of the

editors or of the Institute.

Co-Editors:

Tonya Kowalski, Michael Hunter

Schwartz, and Sandra Simpson

Co-Directors:

Gerald Hess and Michael Hunter

Schwartz

Consultant:

Sophie Sparrow

Advisory Committee:

Megan Ballard (Gonzaga)

R. Lawrence Dessem (MissouriColumbia)

Olympia Duhart (Nova

Southeastern)

Keith A. Findley (Wisconsin)

Steve Friedland (Elon)

Barbara Glesner Fines (UMKC)

Dennis Honabach (Northern

Kentucky)

Tonya Kowalski (Washburn)

Paula Manning (Western State)

Margaret Sova McCabe (New

Hampshire)

Nelson Miller (Thomas Cooley)

Lu-in Wang (Pittsburgh)

©2013 Institute for Law Teaching and

Learning. Gonzaga University School of

Law and Washburn University School of

Law. All rights reserved.

ISSN: 1072-0499

| SPRING

20092013

2 | THE LAW

LAWTEACHER

TEACHER

| SPRING

Remember the Water Buffalo

— continued from page 1

Law professors are very proficient at

spotting all species of water buffaloes.

Some species are easy to spot. Those

are the students who once exhibited

an enthusiasm for learning but now

sit in your class shoulders slumped,

fearful of contributing to discussions.

You know what is going through that

student’s mind: “I worked so hard and

for what? My grades are awful and I’m

never going to get a job.” The bar exam

water buffaloes are also obvious. They

tend to shuffle around the law school

looking unkempt with rather wild eyes

and mumbling to themselves. There

are also some species of water buffaloes

that are less obvious. For example, the

student who acts confident but happens

to stop by to say hello. What that student

is really saying is, “Yes, I did well last

semester but it must have been a fluke,

and I don’t know how I’m going to do

it again,” or “I know I’m going to fail

because I did not understand hearsay/

habeas corpus/future interests, etc.

but there is no way I am going to say

anything because everyone else gets

it.” What all these species have in

common is that they have always been

very successful, and the

emotions they are

now experiencing

are completely

unfamiliar. It is

uncomfortable,

uncertain, and very

disconcerting.

law professor do when she encounters

a water buffalo? Unfortunately, just like

the law, there is no perfect answer.

Some professors

react to the herds by

ignoring them because

those animals just

need to “suck it up and

deal with it.” Others

attempt to domesticate these wild beasts

with excessive treats and coos like, “It

will be fine. Trust me.” Both approaches

have their benefits but neither really

addresses the issue, which is that law

school is about getting comfortable

being uncomfortable. So what should a

So dig through your old

school photos, find the worst

of the worst, and display it

proudly on your desk.

Although there may not be an answer,

there is certainly a response, and it is

why I keep that awful picture of myself

on my desk. That photo reminds me that

the student will probably get through

this but pretending not to see it or telling

them the conclusion (“you’ll be fine”)

without the analysis is not the solution.

It reminds me that we all experience

failure, uncertainty, and self-doubt

throughout our lives, and it’s not so

much the experience itself that matters

but how you deal with it. It reminds me

that even though I’m not in eighth grade

(thank goodness), I still feel like a water

buffalo on occasion, and if I’m feeling

that way, chances are other people are

too.

Students invariably see the photo and

some of them ask, ”who is that boy?”

I tell them it’s me (the polite ones act

shocked) and explain why it’s there. I

keep it on my desk to remind me where

I came from and that life is not always

easy, but if I could make it through

that awful time, then I can

get through anything. Does

it immediately solve their

problem? Of course not, but

it does help them realize that

understanding, accepting, and

learning from an experience is

what defines you.

____________

Katherine Silver Kelly is an Assistant

Clinical Professor of Law and Director

of Academic Support at The Ohio State

University Moritz College of Law.

Contact her at kelly.864@osu.edu.

Book Review:

Teaching to Every Student: Explicitly Integrating Skills and Theory in

the Contracts Class by David Nadvorney and Deborah Zalesne

By Gerry Hess

M

ost law professors who

teach first-year courses want

their students to learn some

combination of doctrine, theory, and

analytical skills. In Teaching to Every

Student: Explicitly Integrating Skills and

Theory in the Contracts Class, David

Nanvorney and Deborah Zalesne

provide a valuable resource to help

teachers and their students achieve those

goals.

Zalesne and Nadvorney designed their

book to help teachers integrate three

types of skills in first-year courses: (1)

academic, (2) legal reasoning, and (3)

and theoretical perspective. The book is

divided into three sections accordingly.

Each chapter addresses a specific subskill.

The co-authors’ main goal is to provide

teachers of first-year law students with

practical methods to help student learn

core skills essential to their success in

law school and beyond. Consequently,

each chapter begins with a background

about the skill and its importance for

students’ success in law school, on the

bar exam, and in practice. The heart

of each chapter is detailed exercises

teachers can employ to explicitly teach

the skill along with legal doctrine. The

exercises can be assigned as homework,

used in class, made part of an on-line

supplement to the course, or become part

of an academic support complement to

the course.

Teach to Every Student is directly

applicable to teachers of Contracts

Section I – Academic Skills

Chapter 1 – Preparing for Class (Case Briefing and Beyond)

Chapter 2 – Close Case Reading

Chapter 3 – Note Taking and Active Listening

Chapter 4 – Outlining

Chapter 5 – Exams

Section II – Legal Reasoning and Analysis Skills

Chapter 6 – Working with Facts

Chapter 7 – Working with Rules

Chapter 8 – Issue Spotting

courses. The exercises are built around

Contracts cases and appendices include

a sample Contracts syllabus and edited

version of each case addressed in the

exercises.

Nadvorney and Zalesne have lots to

offer teachers of any first-year course.

Most of the exercises are easy to

adapt to another course, although the

applicable cases would be different, of

course. For example, in the Academic

Skills section, exercises address briefing

(including “margin briefs”), note

taking guides, outline flow charts, and

practice exams. Likewise, the Legal

Analysis and Reasoning section contains

exercises dealing with fact analysis,

rule synthesis, the role of policy,

and issue spotting. The Theoretical

Perspectives section describes exercises

in recognizing theoretical perspectives

in judicial opinions and effectively using

theoretical perspectives in advocacy.

Finally, the sample syllabus, although

in the context of a Contracts course, is

an outstanding illustration of how to

make doctrine, skills, and theory equal

partners in a first-year course.

____________

Gerry Hess is the Co-Director of the

Institute for Law Teaching and Learning

and a Professor of Law at Gonzaga

University School of Law. He is available

at ghess@lawschool.gonzaga.edu.

Section III – Theoretical Perspective

Chapter 9 – Recognizing Theoretical Perspectives in Judicial

Opinions

Chapter 10 – Portrayal of Parties

Chapter 11 – Understanding and Critiquing the Role of Race, Class,

Gender, and Sexual Orientation in Judicial Decision Making

Chapter 12 – Integrating Issues of Race, Class, Gender, and Sexual

Orientation Throughout the Course

THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013 | 3

Old Professor Tricks

By Sharon Keller

O

ccasionally I sit in on classes

taught by my colleagues and

I’ve noticed certain practices

and characteristics among those who

have grown gray in the service of

their subject. I share some of these

observations below.

Teach more, assign less. As you become

more conversant with a subject, you can

glean much more from cases than just

what the casebook authors intended.

You can assign fewer cases and use

fewer fact patterns to cover more points.

I remember reading a claim, hopefully

apocryphal, that an old professor said he

could cover the whole of Contracts I just

using Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff-Gordon.

Even were this true I’m sure no one

should try it. The trade-off for using

fewer cases is confusion for students,

especially first years, who fervently want

to believe that each case stands for only

one rule. The balance I see old professors

striking is to go through slightly fewer

cases slower while reminding students

of similarities with past cases and even

with cases to come, which is my next

point.

Presaging. If a professor were a spotlight,

some subject matter would be in bright

relief in the center and some other

material, past and future, would be in

the penumbra. Old professors know

what issue of the past they want to

reiterate and what issue in the future

they want to hint at. One must be careful

to choose these issues wisely and seize

upon them frugally. While it creates

interest and excitement to anticipate

coming developments, nothing will

unfocus a discussion faster than too

much wandering down the byways of

side issues.

The bones of a subject. After one has

taught a subject for a while one gets

a sense of an internal structure for a

course. This is a skeleton hidden in the

body of the material that gives form to

the subject. We professors, being very

bright, are sure that we can analyze

4 | THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013

a subject and identify this structure

in the abstract, but the truth of the

matter is that you discover by practice

what is effective for the purposes of

teaching. That is, it is not only an abstract

structure of the subject that you must

divine; you must be attentive to the way

that an abstract structure resonates

with your experience, professional and

pedagogical, of what sounds in that area

of the law. There are points where you

sense, somehow, that something just

came together. This can be idiosyncratic

– one old professor told me that for him

one such epiphany was the mailbox

rule. Can’t say that was true for me. One

should make a note of such moments

anyway. Your students are exploring a

subject through your eyes while you are

teaching. Where you had your personal

breakthroughs well may be where you

teach most clearly.

Observation of the students is also

a place to determine the teaching

structure of a subject. Try different

approaches and look for the relieved

look of comprehension in the faces of

your listeners. Make a note of that and

develop it more deliberately in your

teaching. I even found useful hints upon

rereading my class notes from my law

school days for classes that I now teach;

I made a special note of the graphs and

models I devised for myself to try to get

the penny to drop before the exam.

Repetition and repeating thematics. Nothing

is taught by saying it once. Despite our

remembrance of being deeply affected

by something someone said to us once,

things are learned because the seed fell

where the ground was cultivated. Old

professors repeat themselves during

the lesson, and also during the week,

the month, the semester, and their next

course. Eventually one catches a look

on the students’ faces that seems to say

“I know that – get on with it you old

warhorse!” when one has hit the nth

repetition of a favorite premise. This is

promising because it suggests that the

students think they know what you

mean. A few more repetitions and they

actually will know what you mean.

You do not have to repeat yourself in

the same words – you can repeat a

concept by looking at it from different

angles. However, there is something

to be said about actual repetition. At

regular intervals in my contracts class

I would reproduce a particular simple

diagram that was intended to show

some aspects of the contracting process.

I would start by slashing a straight line

on the blackboard and always saying

as I did so “This is a timeline …” With

some satisfaction I could hear a few

students reciting the next few lines of the

description with me.

Another contracts professor I know

balls up a sheet of paper from time

to time and throws it to a student

when returning to issues of offer and

acceptance. It is an effective symbolic

statement of common law formation,

showing the accepting party accepting

exactly and only what the offeror is

pitching. These mini-lesson repetitions,

which I’ll call for convenience

“thematics,” can be very effective. I

suspect they arise most often as the

inspiration of a moment in some class

one taught. Do not forget them as they

arise – make a note of them. Often they

embody your own, personal grasp of

the subject and, because of that, your

explanations using your own thematics

will be particularly forceful. A small

arsenal of these can be put to great use.

Predictability – when rhythm replicates

dynamism. When I was little my great

grandfather used to go out at ten a.m.,

sit by the grape arbor in his Adirondack

chair and feed the birds. Although,

or because, I was an antsy little child,

I would like to go out with him and

play in my sandbox at the same time

because it was peaceful around him.

Dynamism is good for classes but there

is also something to be said for peaceful

predictability.

— continued on page 5

Old Professor Tricks

— continued from page 4

Starting classes with a predictable

routine helps students settle into the

learning groove. Ironically it also creates

a sense of movement in the class because

students feel they know how this will go

and that they are now on their way. A

review at the beginning of class putting

the lecture of the day in a context is a

good routine. Old professors seem to

take their time with such reviews – they

do not speed through them. Often they

script their closings as well by including

a tantalizing preview of things to come

and/or some customary ending like

announcements. I’ve seen other endings,

for instance following a developing story

in the news that implicates the subject.

Such news stories are rarely first page

news so there is little worry of repeating

something already in the students’

awareness.

Regrettably, you usually cannot use an

Adirondack chair at the podium. But a

steady, recognizable rhythm can gather

the students’ attention, lend the class

a sense of movement and encourage a

feeling of engagement that rivals that of

the dynamic speaker.

Enjoy your job. On the down side, I recall

an old professor from my first year of law

school whom I cannot endorse. Although

he managed some of the techniques

I have described, his class was not a

good one because of his constant bitter

mutterings and his regarding us, his

class, as though he were gazing into a

bowl of hatching insect larvae. Where

people hate their lives, or humanity

generally, teaching is not such a good

job for them. It will take an effort to be

open enough to learn from such teachers

no matter how many tricks they know.

So, the last point I want to make is that

for your own sake, whether or not your

school rewards the development of skill

in teaching, experiment until you find

some joy in teaching. That seems to

be a key attribute of the venerable old

professor.

____________

Sharon Keller is a Visiting Associate

Professor and the Director of the Academic

Success Program at the David A. Clarke

School of Law of the University of the

District of Columbia. Contact her at

sharon.keller@udc.edu.

The Supreme Court Conference Room:

Legal Writing as Legal Process

By Andrew Jensen Kerr

I

teach at the Peking University School

of Transnational Law in Shenzhen,

China—our two-year Transnational

Legal Practice curriculum is centered

at the intersection of legal writing,

common law method, and US legal

discourse. The international posture

of the course sequence thus fosters the

student’s acculturation to the norms

and traditions

of the American

legal system.

Simulated

networking

events and notes

on email etiquette

share intellectual

space with contract drafting and

appellate mooting.

to Walter Bagehot’s analysis that politics

requires pageantry and symbolism if it

is to have resonance. Law students also

share this zeitgeisty appetite for gossip

and myth. What could be more symbolic

of the unmatched secrecy of the

Supreme Court than its fabled Supreme

Court Conference Room? Only the robed

may cross its threshold while conference

The tactile elegance and ritual of the

Justices’ descriptions only add to the

students’ eagerness to debate.

But if there is an ambition in educational

psychology to contextualize learning,

then I position the Supreme Court to be

an ideal setting in which to explore the

dramaturgy of the law. I suppose I tend

is in session. Indeed, my students guffaw

at the corollary—that Justices themselves

are expected to perform the custodial

work. You mean, Justice Kagan has to

fetch the coffee?!

But I think the Conference Room as

an intellectual construct has unique

pedagogical value as well—how does

Court deliberation and diplomacy

inform how opinions are written? A

major assignment for my students is to

draft a judicial opinion in response to

a hypothetical fact pattern. I frame our

Supreme Court Conference as sort of an

intermediate point in their legal research

on the topic. They’re familiar with the

relevant precedent

and have an instinct

for how the case

may turn. Still, they

are to approach the

conference with a

humble sensibility

and open mind—be

ready to be persuaded by your peers’

arguments. I link them to the Court’s

own web narrative of what happens

behind closed doors. The tactile

elegance and ritual of the Justices’

descriptions only add to the students’

eagerness to debate. I also provide a

— continued on page 6

THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013 | 5

The Supreme Court Conference Room: Legal Writing as Legal Process

— continued from page 5

scholarly article from political science

that questions how things like median

justices and concurrences shift the axial

tilt of a majority opinion (Lupu and

Fowler, “The Strategic Content Model

of Supreme Court Opinion Writing”).

The article relays the usual process of

the Conference Room – we mirror the

procedure. First, each student meditates

aloud for five minutes on law or facts

they consider dispositive (I have the

fortune of teaching small sections;

if there is an even number I appoint

myself the tiebreaker and feign Justice

Kennedy’s wishy-washy tendencies).

Questions or interruptions of any sort

are not permitted during these opening

statements. We then take a tentative vote

as to who should win and intermission

for a quick respite.

The second half of class generally tracks

two forms of debate—close votes mean

having to convince the median justice

to join your side’s cause; less symmetric

balances mean figuring out how to craft

the opinion. In either event there will be

discussion of which party deserves to

win, and more importantly, why. What

is the reasoning the court will use? A

textual argument? Policy-based? By

reference to the Constitution? A broad

holding or narrowed to the idiosyncratic

facts of the present context? I’ve found

my students to be unusually voluble

and perhaps even more profound in this

student-centric classroom environment.

It is understandable that shy or selfaware students may fear questions from

an authority figure such as a professor.

But as hierarchies are flattened in this

peer-driven space these same students

are able to express their ideas with

sophistication and panache.

There are also structural pedagogical

benefits to the conferences. First,

students cannot engage in the facile

“black-white” distinction-making

common to the Socratic Method.

They aren’t challenging a singular

6 | THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013

prompt, but must articulate a more

nuanced, uncertain and “grey” position

contrasting the dozen other students

in the classroom. This spectrum of

variation often requires the student

to form arguments at higher orders

of thinking—“maybe it’s wrong to

frame the debate as a black-white

issue, perhaps the question itself is

misdirected.” Second, the arithmetic

of the Supreme Court becomes more

palpable in this classroom experience.

The sum of how many justices are

part of the majority or concurring or

dissenting opinions can often make the

governing holding obscure or ethereal

for the first year student (especially

in the kaleidoscopic fragmentation of

the contemporary court). This math

becomes more obvious in the drama and

vote counting of the session.

Connected to this Supreme Court

modeling is an initiation to the work

of court clerks. I introduce their job

description and ask the student to

play the role of clerk in the process

of accepting petitions for certiorari.

After they have drafted their judicial

opinion writing assignment, I invite

them to my office to question them on

more ontological matters – I ask them

if this is a case that the Supreme Court

should bother to accept for review.

Alexander Bickel praised the “passive

virtues” of the Court and its sensitivity

to political timeliness (see Sanford

Levinson’s article, “Assessing the

Supreme Court’s Caseload: A Question

of Law or Politics?”). Should the Court

devote its scarce resources to more

pressing issues? Maybe the common

law can evolve at the trial or appellate

level to find the most efficient solution?

As Justice Brandeis famously enjoined

in New State Ice Co v. Liebmann, let the

states be the laboratories of democracy.

This play on judicial process allows the

student to consider opinion writing at

first principles – should I write this and,

if so, how?

I attempt to structure my curriculum so

that legal process tracks the discourse

of legal writing. The opinion writing

assignment is taught within the universe

of the Supreme Court; appellate brief

writing and mooting are taught as an

introduction to the adversarial system

(vis-à-vis the inquisitorial nature of

the civil law). However, I think this

general “conferencing” exercise is fairly

fungible and can be applied to different

parts of a legal writing curriculum;

for example, as part of a section on

memo writing and litigation strategy

within a law firm. The conference is

translated into an office setting where

students posit different strategies and

their likely traction for a judge or jury.

Again, the forgotten element of math

in law is surfaced – students learn to

think probabilistically. “Well, a statutory

argument has a 60% chance of success;

are these adequate odds to go to trial?”

This kind of discussion also lends itself

to another topic too absent from the 1L

curriculum – the ubiquity of settlement

in the American legal system.

Role playing should be regarded as a

uniquely experiential tool available

to law teachers. Indeed, front-rank

programs such as the NYU Lawyering

curriculum already make use of

simulated instruction in negotiation

and counseling exercises. I argue

that the Supreme Court Conference

is of similar value – the student

becomes familiar with the institutional

processes of opinion writing and

becomes empowered to speak with an

authoritative voice on the law.

____________

Andrew Jensen Kerr is a Senior Lecturer

at the Peking University School of

Transnational Law. He can be reached at

kerra@stl.pku.edu.cn. He thanks Eric Mao

for his inspiration.

Infusing Ethics into the Legal Writing Curriculum—and Beyond

By Almas Khan

A

s teachers of sequential courses

that are increasingly spanning

from the first year of law

school into the second and third years,

legal writing professors are uniquely

positioned to underscore a component

of the law school curriculum that until

recent times shared legal writing’s

subsidiary status—legal ethics.

Before 1974, when the American Bar

Association responded to the Watergate

scandal by enacting Standard 303(a)

(ii), which requires all ABA-accredited

institutions to

offer a mandatory

course in

professional

responsibility,

professional

responsibility

classes were

a “cipher” in

the curriculum of the law schools

that offered them. In a story that may

resonate with legal writing faculty,

professional responsibility courses

continued to languish after the

standard’s adoption, often allocated

minimal credits and assigned to

adjunct faculty or new law professors

as a rite-of-passage. To enhance the

course’s reputation and entice student

interest, professional responsibility

teachers became curricular innovators,

incorporating visual aids, role-play and

problem-solving exercises, and literature

into their classes while coalescing into a

scholarly community.

ethics for impressionable law students.

During orientation, legal writing faculty

can collaborate with the Honor Council

to emphasize the importance of seeking

counsel when confronted with ethically

challenging situations, reserving a more

detailed discussion of professional

responsibility in the legal writing

context for class.

Legal writing professors can employ

variegated methods to incorporate

ethical instruction in their courses

from the first day of class (which may

into problems analyzed for assignments

can fulfill course objectives and instill

appreciation for rules of professional

conduct that will guide students’ legal

careers.

Coordinating ethics instruction with

clinical and doctrinal faculty can ensure

that legal writing students receive

a relatively comprehensive (but not

unduly repetitive) introduction to the

subject, and partnering with the career

services center to sponsor a guest

speaker series centered on professional

responsibility can

complement class

instruction. For

example, during

the fall semester,

interactive panels

with upper-division

students and

attorneys can focus

on ethical objective legal writing. In

the spring semester, when most firstyear legal writing courses transition

to persuasive writing and 1Ls seek

summer employment, panels with

judges, trial and appellate attorneys, and

upper-division students with summer

internship experience may be apposite.

Requiring students to prepare questions

for the panelists and reflect on ethical

insights gleaned from the presentations

can generate a virtuous circle between

legal writing courses and legal practice

while inculcating the four values

identified by the seminal MacCrate

Report—competent representation;

striving to promote justice, fairness,

and morality; striving to improve

the profession; and professional selfdevelopment—endemic to upstanding

lawyers.

To enhance the course’s reputation

and entice student interest, professional

responsibility teachers became

curricular innovators­…

Professional responsibility instruction

now increasingly pervades clinical,

doctrinal, and legal writing courses,

and legal writing professors are

optimally situated to introduce and

reinforce ethical rules governing

attorney conduct before first-year law

students commence studies, during

legal writing classes, and outside of

class. Many law schools disseminate

suggested summer reading lists for 1Ls,

and books implicating an attorney’s

professional responsibilities can readily

be included in these lists; alternatively

(or in addition), legal writing professors

can assign these texts near the outset of

the first semester, foregrounding legal

coincide with orientation) onward. Scott

Fruehwald covers three legal ethics

topics in his first session with students:

“the role of the lawyer, the duties of a

lawyer to both the client and society,

and how easy it is for an attorney to

get into trouble.” Plagiarism is another

imperative subject to introduce in this

preliminary class and revisit as students

develop familiarity with the distinction

between legal writing conventions

and attributions to authority in their

undergraduate or graduate disciplines.

Requiring students to read and attest

to understanding the law school’s and

the legal writing course’s plagiarism

policy, and demonstrating how the

policy applies through progressively

challenging exercises, can be effective.

Also, beginning class with memorable

ethical anecdotes related to the topics

under discussion for the day (e.g.,

accurately representing authority in a

brief) can stimulate students’ interest

in the subjects while highlighting how

ethical considerations permeate legal

writing. Assigned readings, such as

Melissa Weresh’s book Legal Writing:

Ethical and Professional Considerations,

which includes case excerpts on ethical

issues arising in legal writing, can

instigate perceptive class discussions.

Finally, integrating ethical concerns

____________

Almas Khan formerly taught legal writing

at the University of Miami School of Law

and the University of La Verne College of

Law and is currently a doctoral candidate in

English concentrating on law and literature

at the University of Virginia. Contact her at

bak4pr@virginia.edu.

— continued on page 8

THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013 | 7

Infusing Ethics into

the Legal Writing

Curriculum—and

Beyond

— continued from page 7

Mary C. Daly, Bruce A. Green & Russell

G. Pearce, Contextualizing Professional

Responsibility: A New Curriculum for a New

Century, 58 Law & Contemp. Probs. 193, 194

(1995).

1

2

Id. at 194-97.

See, e.g., Scott J. Burnham, Teaching

Legal Ethics in Contracts, 41 J. Legal Educ.

105 (1991); Margaret Z. Johns, Teaching

Professional Responsibility and Professionalism

in Legal Writing, 40 J. Legal Educ. 501 (1990);

Introduction to Lawyering: Teaching First-Year

Students to Think Like Professionals, 44 J. Legal

Educ. 96 (1994).

3

See generally Jamison Wilcox, Borrowing

Experience: Using Reflective Lawyer Narratives

in Teaching, 50 J. Legal Educ. 213 (2000).

4

Edwin S. Fruehwald, Legal Writing,

Professionalism, and Legal Ethics 2 (Hofstra

Univ. Sch. of Law Legal Studies Res. Paper

Series, Res. Paper No. 0820, 2008), available

at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.

cfm?abstract_id=1238484.

5

See generally Terri LeClercq, Failure

to Teaching: Due Process and Law School

Plagiarism, 49 J. Legal Educ. 236 (1999).

6

See Judith D. Fischer, The Role of Ethics in

Legal Writing: The Forensic Embroiderer, the

Minimalist Wizard, and Other Stories, 9 Scribes

J. of Legal Writing 77 (2003-04) (classifying

anecdotes).

7

Melissa H. Weresh, Legal Writing: Ethical and

Professional Considerations (2d ed. 2009).

8

See Philip M. Frost, Using Ethical Problems

in First-Year Skills Courses, 14 Perspectives:

Teaching Legal Res. & Writing 7 (2005).

10

See John M. Speca, Panel Discussions as a

Device for Introduction to Law, 3 J. Legal Educ.

124 (1950-51).

11

See Am. Bar Ass’n Section on Legal Educ.

and Admissions to the Bar, Legal Education

and Professional Development – An Educational

Continuum, Report of the Task Force on Law

Schools and the Profession: Narrowing the Gap

135-36 (1992) (deemed the MacCrate Report in

honor of Robert MacCrate, chair of the blueribbon task force that issued the report).

9

Book Review:

How Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and

the Hidden Power of Character By Paul Tough

By Devin Kinyon

I

heard Paul Tough in an interview

on This American Life, relaying one

of the stories from his book, How

Children Succeed: Grit, Curiosity, and the

Hidden Power of Character. It’s the story

of the marshmallow test, an experiment

conducted in the 1960s at Stanford on

willpower. The test was administered

to four-year-olds in a preschool. Each

child was placed in a room with a desk,

and on that desk was a plate with one

marshmallow. The child was told that

he or she could have the marshmallow

now by ringing a bell to call in the

experimenter, but, if the child could wait

until the experimenter returned on his

or her own, the child would receive two

marshmallows.

The radio show played an audio clip of

a boy being subjected to the experiment

by his parents at home. I was sold on

Tough’s book when I heard that sound

clip; in it you hear a child named

Theo saying over and over to himself,

“ten minutes… ten minutes… TEN

MINUTES!” There are pangs of want in

Theo’s voice, doing anything he can to

cope with waiting for the opportunity

to get two “sweeties” instead of just

one. You can watch the clip on YouTube.

Spoiler alert: Theo did last ten minutes

and got two sweeties. And the reason

Theo could hold out seems to be his

learned ability to control and distract

himself, to be patient and cope.

On the surface, the radio show seemed to

imply that Tough’s book was a discussion

of the character attributes of those who

persevere in school and in life, kind of a

Seven Habits of Highly Effective People for

the educational reformer. What made

Tough’s book more interesting to me,

however, was how he put together so

much research by doctors, psychologists,

economists, and educators, experimental

research in labs and observational

projects in schools and communities.

And that research seems to point in the

direction that success in school and in

life is tied to a child’s character. (Tough

switches terminology throughout the

book, using the terms “noncognitive

behaviors” and “soft skills”)

The book begins by introducing James

Heckman, an economist at the University

of Chicago who has done extensive

research on the GED. Heckman’s

research looked at those people who

have passed the GED to see if their longterm outcomes are similar to people

who graduate high school. They are

not. He had believed that the process

of learning material to take and pass

the GED, which tests basic math and

science, reading and writing, and social

studies, was indicative of future success;

that the cognitive development tested

on the GED was the key to employment,

family stability, and prosperity. But his

research showed that those who passed

the GED have the same future outcomes

as high school drop-outs. This discovery

took his work on a new path, raising the

question of why some students can bear

the tedium of high school and others

can’t.

Tough connects Heckman’s research

to the earlier mentioned marshmallow

experiment. About twelve years after

the initial marshmallow tests, a different

researcher tracked down the original

study participants. Those who had been

able to wait for the researcher to return,

thereby receiving two marshmallows

instead of one, had SAT scores that

averaged 210 points higher than the

subjects who’d gone for the single

marshmallow. Like students who can

survive high school, those who could

wait to earn the second marshmallow

— continued on page 9

8 | THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013

Book Review:

How Children Succeed

— continued from page 8

had some strength of character that

propelled them forward with lasting

effects. This is the core question explored

in How Children Succeed: why do some

kids make it while others don’t?

Poverty tends to be the default answer,

and the research in Tough’s book points

in that direction, but not for the obvious

reason. He discusses a thread of public

health studies regarding the stress

that comes from “adverse childhood

experiences,” a clinically-detached

term for poverty, violence in the home,

neglect, single- or no-parent families,

and coping with addiction, mental

illness, and incarceration. Living in this

type of environment impacts the body’s

internal hormonal balance. Humans’

stress hormones came out in short bursts

in pre-modern times, as in the need for

a shot of adrenalin to outrun a charging

beast. But modern humans live under a

continuous stream of stress hormones

caused by the ongoing daily stressors

in their lives. For children growingup in homes under continuous stress,

their hormonal system is in overdrive.

The researchers use the metaphor of a

fire hose: effectively these children are

flooded with stress hormones all day,

every day. The principal impact of this

stress hormone flood is the reduced

ability to manage emotional behaviors

leading to poor academic performance,

and a likelihood of adult health problems

ranging from heart disease and obesity,

to smoking, depression, and risky sexual

behaviors. Subsequent experiments

show that when all other factors are held

constant, weak learning outcomes by

students who grew up in poverty are

closely aligned with hormonal stress

load. The researchers found that it isn’t

poverty itself that is defeating these

children; it’s the stress that goes along

with it.

To illustrate this distinction between

poverty and stress, Tough interviews

teachers at an elite private high school

in New York State. Their wealthy

students are not subject to the same

types of stressors as poor students.

Notwithstanding, the teachers still see

similar gaps in the students’ character

development. These students, with

extreme pressure to achieve and

succeed, display many of the same

unhealthy outcomes as poor students.

Tough reports on research showing that

wealthy white suburban youth have

comparatively higher rates of substance

use and abuse, depression, and other

mental health issues. The difference

between the wealthy students and poor

students is often a parent advocating

on the wealthy student’s behalf, making

demands on the school and ratcheting up

the expectations of the student, further

increasing the stressors in the student’s

life. Instead of helping their children

manage their stress, they paper over it,

which further exacerbates it in the long

run.

The silver lining to Tough’s oftendepressing book is that high stress levels

can be mitigated through intentional

character-building activities. By helping

students and children build their

portfolio of noncognitive skills, teachers

and parents can decrease the likelihood

of the long-term negative outcomes. This

is a lesson that shouldn’t be surprising

to anyone who teaches, parents, or

works with young people—it’s strong,

supportive relationships that counteract

much of the stress-caused character

deficits. How Children Succeed highlights

many such successful relationship-based

interventions, primarily in schools and

youth programs. There are lots of good

ideas for teaching children how to wait

to earn a second marshmallow.

I know who The Law Teacher’s target

audience is, and don’t imagine many

of you torture your students with

marshmallow experiments. But the entire

time I was reading How Children Succeed,

I was thinking about the law students I

work with every day. I’m an academic

support professor, so my work deals

with students who aren’t performing

well for one reason or another. Very

often the students who come through

my door or sit in my classroom reflect

many of the problematic outcomes that

Tough’s researchers observe. There

are those who have been so pushed to

achieve by their families and own selfdrive that the slightest stumble reduces

them to tears. And there are the students

who overcame significant obstacles to

make it to college and into law school,

struggling to balance the old world they

came from with the new professional

class they are about to enter. I see in most

of my students the impacts of the stress

in their lives before they arrived on our

campus, and the stress that is piled on

each day. And while most of them will

survive to join our profession, their stress

will continue to intensify, leading many

to substance abuse, mental health issues,

and questioning why they chose to study

the law in the first place.

Tough’s book is an important reminder

that helping a student lay out a

thoughtful hearsay analysis, for example,

isn’t likely to help him or her succeed

in the long run if we don’t have other

supports in place to nurture their soft

skills. The students I’ve seen turn

around from initial weak law school

performance universally exhibit the

noncognitive abilities that How Children

Succeed explores. They’ve learned to

bounce back from defeat and to place

their trust in supportive relationships

with faculty and advisors. This book was

a welcome reminder of how essential

this work is, and that the development

of character and interpersonal skills can’t

be an afterthought in legal education.

Successful law students and lawyers

need soft skills.

Paul Tough’s How Children Succeed

certainly isn’t a roadmap for law schools

(or schools and colleges, in general), and

leaves many questions to be researched.

But for law teachers interested in

thinking about how to support students

and why they might be struggling, this

book is a good place to start.

____________

Devin Kinyon is Assistant Clinical Professor

of Law and Assistant Director of Academic

Development at Santa Clara University

School of Law. He can be reached at

dkinyon@scu.edu.

THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013 | 9

It’s OK to Leave Law School

A Note from an Anonymous Former Student, Sent to Professor Jan M. Levine

I

began law school teaching in 1980 as

an adjunct, and I have been a fulltime professor since 1986. Because I

teach legal writing, a course that is built

upon much individualized interaction

with my students, I get to know those

students very well. The five law schools

where I have taught have been unique

institutions, located in diverse places,

and with quite different types of

students. Despite those variations one

common event has been the discussion

held with a first-year student who is

considering departing from law school.

Although there are many reasons for

a student to consider such a departure

before the end of the first year, the most

common include unhappiness with the

study of law, growing dissatisfaction

with new insights into law practice,

and receipt of weak interim or mid-year

grades.

These discussions are not easy ones for

either student or teacher, but I have been

flattered and touched that these students

have come to me in an effort to seek

advice or unburden themselves. It is not

common to hear from such students after

they leave, but recently I did receive a

note from one of my former students

who left school in mid-year. His note

was articulate and came straight from

the heart, and he gave me permission

to share his thoughts with others in the

hope that it would be helpful to anyone

struggling with the same circumstances

he faced.

Here is that note, edited slightly for

clarity from the original e-mail, and with

the student’s identifying information

removed. We both hope you share it as

you see fit.

I’m not sure if you will remember this,

but I was a 21-year-old student in your

legal writing class many years ago.

About two-thirds of the way through the

fall semester, I had a bit of an existential

crisis, and came to you looking for

advice. It was pretty apparent that if I

sat for exams, I would not do very well; I

knew I would perform well below what

I was capable of. I ultimately decided to

10 | THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013

withdraw from school, knowing that I

could start over the following year with a

clean slate, if I was so inclined.

Anyway, the reason I’m writing to

you is because I remembered recently

something you had said, that you rarely

knew what happened to your students

who were like me and decided to leave

law school. I had wanted to write to

you sooner, but honestly, I didn’t have

much perspective to really say anything

worthwhile.

Honestly, talking to you made me feel

like it was OK to leave law school, that

it wouldn’t be the end of the world, and

that it was not a matter of life or death.

I really needed to hear that. So I thank

you. The school had graciously offered

to let me re-matriculate the next year, but

honestly, once I took a step back and let

out a sigh of relief, I knew pretty much

immediately that I would never go back,

that I did not want to go back, and that I

had absolutely no desire to be a lawyer.

I didn’t rush to any decisions, but over

the next few months it became more and

more undeniable.

So I never went back to law school, a

decision I never regretted for a second.

I can’t say that my career was easy once

I made that decision. I still didn’t have

a clue what I actually wanted to do, and

spent several years working mediocre

jobs I didn’t care about and made no

money at, but didn’t really have to

put much effort into. I actually got out

there and saw what my options were,

and figured out what I actually was

interested in and cared about. I made

an abortive attempt at graduate school

soon after that, which didn’t pan out,

but I did end up going back to graduate

school again about a year and a half ago.

I studied computer science, enjoyed it

immensely, did awesome in my classes,

graduated, and recently started a new

job I am really excited about.

I don’t know how helpful this e-mail

will be, to anyone. My circumstances

are somewhat unique, but most peoples’

are. The prospects for legal jobs have

changed enormously (I may have

actually dodged a bullet, but that’s

neither here nor there.) To those of

you who are upset and agitated about

their decision to go to law school,

who are freaking out because they’ve

based all these insane expectations

on having brilliant legal careers, who

are completely miserable and beat

themselves up constantly, this is my

advice: it will be OK. If you decide to

leave law school, it’s not the end of

the world. Putting all that pressure

on yourself is just going to dig you an

early grave. You can’t make yourself be

passionate about something you don’t

like. If you are really that miserable, it’s

OK to take a step back and let yourself

breathe; there is absolutely no reason to

be embarrassed or self-conscious about

it.

There is an awful tendency in humans

to be terrified of failure, and to avoid it

like the plague, above all else. The idiotic

notion that if something doesn’t work

you should just keep bashing your head

against the wall, and the feeling of being

so embarrassed over the quintessentially

human act of making an honest mistake,

just destroys people. Being realistic and

adaptable is one of the most important

human qualities, not a dark secret to

hide in shame.

I don’t know if any of this was as helpful

as what you told me. This has just

been my experience. But if it helps just

one student find their way, then I’ll be

ecstatic. I’m sorry if it’s a bit wordy and

rambling; my writing isn’t as disciplined

as it once was.

I hope everything is going well for you.

Thank you again.

____________

Jan M. Levine is an Associate Professor

of Law and the Director of the Legal

Research and Writing Program at

Duquesne Univ. School of Law.

Contact him at levinej@duq.edu.

JUDICIAL POWER

(C) 1995 Ashley S. Lipson, Esq.

Across

1.

This "international" company left a permanent

footprint on the law of interstate jurisdiction.

14. Vehicles for the exercise of judicial power.

4.

Advanced law degree.

7.

Criminal Prosecutions Limitations Act.

19. King's knight's pawn.

11. Actor Neuman, who played lawyer in several films

and television segments (Initials).

12. International Union of United Automobile,

Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of

America.

13. Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society.

18. One entitled to allegiance and service.

20. Impress.

22. Famous ancient judge.

24. Lower life form but very rule-oriented, nevertheless.

25. Set of tools.

27. Continuously variable transmission.

28. Environmental Impact Statement.

— continued on page 12

THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013 | 11

JUDICIAL POWER

Across — continued from page 11

29. Speech Association of America.

42. Form of money used in ancient Rome.

31. Law firm's venue.

44. A past perfect crunch.

32. Emergency equitable relief where there exists a

threat of immediate and irreparable harm, without

an adequate remedy at law.

45. Verified.

33. Guaranteed Student Loan.

49. Spanish pot for holding water.

50. Aborted fish eggs.

51. Iron.

35. Globe.

37. The right of the oldest member of a coparcenary to

have first choice of share of an inheritance (English

law).

40. Part of the Federated States of Micronesia.

52. Canadian revolutionary.

53. Standard Book Number.

54. One who exercises his or her right to enjoy

property.

Down

1.

Became associate justice of the Supreme Court in 1986.

23. Intimidate.

2.

Argumentative, leading, privileged, vague, and

speculative questions.

26. Mark evidence.

3.

City in Nigeria.

4.

Unlawful state for motor vehicle operator.

32. Frequently used by Einstein to transfer among

coordinate systems.

5.

Criminal slang for money.

34. Personification of fire.

6.

Oscillated.

36. New York based law book publisher.

7.

UCC term indicating a price of goods which includes

cost, freight, and insurance.

38. Feline.

8.

Weak states shielded by stronger one.

9.

Local area network.

41. Disorder.

10. Concur in an opinion.

30. Examine a witness.

39. Measure for most statutes of limitation.

43. Self-impressed connoisseur.

15. Meals.

46. Underwriters Laboratories, Inc. (Environmental

law acronym).

16. Legal furniture.

47. Male name, form of Salvatore.

17. Turns per inch.

48. Number of the "states' rights" amendment.

21. Environmental Impact Statement (Environmental law

acronym).

Crossword solution is on page 36

12 | THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013

Eliminating the Blackacre Opportunity Cost

Using Real-World “Targeted Fact Environments” in First-Year LR&W Courses

By Charles E. MacLean

G

enerations of law school

students have wrestled with law

school fact patterns regarding

Blackacre, or Dewey, Cheatem, & Howe,

and so on, as they learned to apply

the law in one law school course after

another. And first-year legal research

and writing (“LR&W”) students are

obliged to survive whatever more-orless vetted fact patterns the program

or professor or text has provided that

year. If a substantial portion of first-year

LR&W assignments grew instead out

of a single “targeted fact environment,”

with real-world value, those first-year

LR&W students would still learn the

same legal research and writing skills

and resources, but would also perforce

learn about the contours and depth of

the targeted fact environment. And

when that targeted fact environment

is relevant to achieving a key part of

the law school’s vision or mission, and

involves a real-world set of important

legal issues confronting real people

and institutions in our communities,

that provides a springboard for

teaching all the same legal research

and writing skills many have used

Blackacre-type scenarios to transmit

up to now, but also creates motivated

first-year LR&W students, informs an

entire cohort of students about critical

legal problems in our communities,

gives life to our law schools’ mission

statement pronouncements that we are

committed to diversity, pro bono service,

community outreach, etc., provides

important legal research to non-profit

agencies and needy people in our

communities, and fosters a student body

that values pro bono service as a natural

outgrowth of our profession rather than

a chore or afterthought.

To start on this critical path, a LR&W

professor or program only needs: (1) a

community constituency in need, (2) a

substantial legal problem or set of legal

problems confronting that constituency,

(3) a cooperative LR&W director and

academic dean, and (4) enough time to

craft or obtain a broad scenario on point

and weave it into the LR&W assignments

throughout the year. Failing to take this

path is a decision to continue to pay the

Blackacre opportunity cost.

Why in LR&W Classes?

Whatever pedagogical quest is realized

within an upper level elective benefits

only those few students who take the

elective. On the other hand, every

student in each cohort must take LR&W

in the first-year curriculum. Thus,

LR&W students are a captive audience.

Whatever pedagogical quest one realizes

in the first-year LR&W program benefits

every student in that entire cohort. There

is a clear opportunity cost when we fail

to achieve something a bit more grand

in those first-year LR&W courses. The

answer lies in simply using targeted

fact environments on which to base

a good share of the first-year LR&W

assignments instead of relying on the

Blackacre fare many now use.

Within a single “targeted fact

environment” lies the source material

for assignments useful in every LR&W

course module: (1) statutory, rule,

caselaw, and secondary research, (2)

Bluebook or ALWD citations for that

research, (3) predictive writing and oral

presentation, (4) persuasive writing and

oral argument, and (5) every other topic

and sub-topic in any LR&W course.

Using such a targeted fact environment

throughout the first-year LR&W

curriculum would create a cohort of

students, who, having taken that course

with that “targeted fact environment,”

will have developed all the same legal

research and writing skills that would

have been learned using the traditional

random “Blackacre” fact pattern

construct, but with a real and abiding

knowledge of issues involved in that

targeted fact environment. Sounds like a

win-win.

Sources for Targeted Fact

Environments

Once a program or professor chooses

to use the targeted fact environment

framework, the next task is to determine

the target. Possible sources for targeted

fact environments include: (1) the law

school’s mission and vision statements,

(2) the ABA Standards, (3) local

newspapers, and (4) area non-profit or

governmental organizations serving the

needs of area clients.

From School’s Vision/Mission

Statements:

Let’s say the law school’s mission

statement provides that the school is

committed to serving “humanity,” and

“underserved rural communities in the

Appalachian region.” In the light of the

highlighted portions of that law school’s

mission statement, the LR&W program

or professor may choose to devise a

targeted fact environment that focuses on

an assemblage of legal issues and legal

needs confronting rural communities

in Appalachia, such as utility shut-offs,

uninsured or underinsured medical

care, homelessness, alcoholism and

drug abuse, social security, Medicaid

and Medicare eligibility, SSI disability,

workers’ compensation, and the like. In

that way, in the first year, law students

are confronting and learning about issues

that may otherwise be covered in law

school, if at all, only through electives

touching only a small percentage of

each cohort. Placing those issues, via

the targeted fact environments, into

first-year LR&W courses guarantees

that every matriculant will be exposed

to and will develop an awareness of

those precise legal challenges the law

school felt were important enough to

incorporate into its vision or mission

statements. Any key quest identified

in any law school vision or mission

statement can serve as a rich source of

ideas for targeted fact environments.

— continued on page 14

THE LAW TEACHER | SPRING 2013 | 13

Eliminating the Blackacre Opportunity Cost

— continued from page 13

From ABA Standards:

One example will suffice to illustrate the

concept. ABA Standard 302 provides in

part that each law school “shall” offer

substantial opportunities for student

pro bono activities, which may be creditbearing or not. Thus, a targeted fact

environment in a credit-bearing LR&W

course could focus on the real needs

of persons and institutions in need in

our communities. For example, a local

social service agency serving homeless

veterans or crime victims could benefit

from legal research (even from first-year

law students) on matters confronting

their clients. The benefit to the outside

agency is clear, but the benefit to our

students is even clearer. Instead of

rolling their collective eyes at yet another

make-believe Blackacre scenario, those

first-year LR&W students would be

tasked to do what many of them came

to law school to do – help others. This

would energize and involve the LR&W

students, and improve student learning

outcomes. Another win-win.

From Today’s News:

As one recent example, a local explosion

of sorts arose of late from a particularly

egregious case of judicial misconduct

in the Knoxville area. That could have

yielded a number of real-world and

engaging targeted fact environments.

The scenario played out as follows

based on court findings. A trial judge

routinely consumed 10-20 Oxycodone

tablets on days when he was presiding

in a series of high-profile murder trials

over a period of several years. He had

obtained some of those pills from a

felony probationer he had himself

sentenced. The Judge also obtained

sexual favors from that probationer, at

times in his chambers. The Judge even

fell asleep during more than one of those

murder trials. Eventually, the Judge was

prosecuted for Misconduct in Office and

entered into a diversion agreement. The

successor judge, serving as thirteenth

juror in a number of those murder trials,

found structural error, and cast doubt

on all the murder convictions, since the

original Judge had not been competent

to preside.

The targeted fact environment could

have addressed chemical dependency,

right to fair trial, due process, structural

error, professional responsibility, and

the like. They would study the issues on

one day, and read the latest news and

developments the next. Another winwin.

From Collaborations with

Non-Profits:

Perhaps the most fool-proof way to

obtain nearly all the advantages of

using targeted fact environments in

first-year LR&W classes can be realized

by partnering with a non-profit agency

serving persons in need in the areas

around our law schools. Depending on

the collaboration, the agency chosen,

and the topics at issue, that approach

would help achieve law school vision

and mission statement goals, inculcate

pro bono energy in our LR&W cohorts,

serve our hinterlands, energize a cohort

of LR&W students by having them

help real neighbors with real problems,

respond to and achieve ABA Standards,

and ensure that entire cohorts (and not

just select students taking later electives)

will be informed about key issues and

constituencies selected by the school.

Conclusion

Using this targeted fact environment

approach would create a more relevant

first-year LR&W experience, inform

and energize an entire captive cohort

on issues of import to our communities,

provide a public service, help our

students make a difference in the

first year, and avoid or eliminate

the Blackacre opportunity cost. And

this path would further crystallize

some of the recent literature on ways

to incorporate LR&W into doctrinal

courses, meld LR&W and clinical

courses, create more practice-ready

graduates, improve our relevance and

footprint in our communities, help meet

enhanced ABA scrutiny, and enhance

pro bono service mindsets. What Dean

would oppose teaching the same skills in

LR&W, while simultaneously gaining so

many other benefits? Law schools cannot

afford the Blackacre opportunity cost

any longer, so as part of the shift toward

experiential learning and practice-ready

graduates, law schools should adopt

targeted fact environments for first-year

LR&W courses.

____________

Charles E. MacLean is an Assistant

Professor at Lincoln Memorial UniversityDuncan School of Law. Contact him at

Charles.MacLean@lmunet.edu.

Submit articles to The Law Teacher

The Law Teacher encourages

readers to submit brief articles

explaining interesting and

practical ideas to help law

professors become more effective

teachers.

THE

LAW

TEACHER

| SPRING

20132013

| 14

14

| THE

LAW

TEACHER

| SPRING

Articles should be 500 to 1,500 words

long. Footnotes are neither necessary nor

desired. We encourage you to include

Please e-mail manuscripts to Barb

Anderson at banderson2@lawschool.

gonzaga.edu. For more information

contact the co-editors: Tonya Kowalski

at tonya.kowalski@washburn.edu,

and Sandra Simpson at ssimpson2@

lawschool.gonzaga.edu.

Reflection, Reality, and a Real Audience: Ideas from the Clinic

By Dana M. Malkus

F

or a variety of reasons too

numerous and complex to recount

here, law teachers are increasingly

expected to provide law students with

more feedback and assessment. This

is especially true for those who teach

“doctrinal” courses. As a clinician,

frequent feedback and assessment are

common and essential parts of my

teacher-student relationships. I believe

the clinical model provides at least three

simple—but important—lessons that can

inform all law teaching.

First, law teachers should provide

students ample opportunities to

practice reflective self-assessment.

Clinical legal education—like many

other disciplines—places a high value on

reflective self-assessment. At their core,

lawyers are problem-solvers. In my view,

effective and creative problem-solvers

are those who admit to, and learn from,

mistakes (rather than being held captive

by the fear of making them). My goal is

to help students learn to self-assess so

that they can grow from each experience

and continue to improve their skills in

practice. I want self-reflection to become

a habit for my students because I believe

it will make them more competent

problem-solvers and better professionals

(whether they practice law or pursue

some other work).

Self-assessment is a useful tool that

law teachers can employ for a variety

of purposes, including (1) empowering

students to take an active role in their

own learning, (2) motivating students

to more fully engage with the course,

and (3) helping students develop into

more competent professionals able to

both tackle a variety of client problems

and manage the consequences of their

own (inevitable) mistakes. Reflective

self-assessment is a skill that should be

taught not only in the clinical setting,

but throughout the entire curriculum.

Here are three ideas for helping students

develop this skill:

1.In a course where written assignments

(of any kind) are used, ask students to

answer simple reflection questions as

part of the assignment. For example:

What do I like most about this work

product? What am I most concerned

about with respect to this work

product? How much time did I spend

on this assignment?

2.Ask students to answer simple

reflection questions when you hand

back any graded assignments. For

example: What is one thing I did

well on this assignment? What is one

mistake I made that I will correct in

future work product?

3.Ask students to reflect on their

experience with the course. For

example: What should I start doing

that I am not already doing? What

should I stop doing that I am currently

doing, but which is not working very

well? What should I continue doing

because it is working well?

Second, law teachers should bring

reality into the classroom whenever

possible. In the clinic, I generally enjoy

motivated students. Students are

motivated—at least in part—because

they are working on real matters

with real clients and have real ethical

responsibilities to those clients. In

addition, they are interacting with real

lawyers, making professionalism and

networking concrete realities. The “realness” factor also motivates me. I am

motivated to give students frequent and

concrete feedback, not only because it

is my professional duty to do so, but

because they are practicing under my

license.