Enforcement of Promi..

advertisement

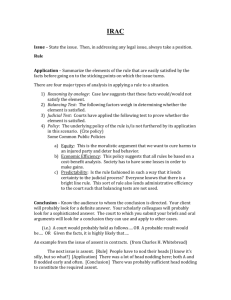

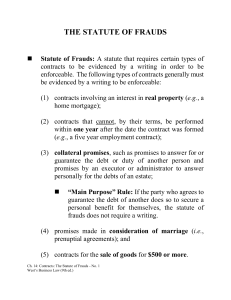

Contracts (O'Byrne) The Requirement of Writing (Introduction) TOPICS: A. B. C. D. E. F. G. Why do certain kinds of contracts have to be reduced to writing or evidenced by writing? What are the rationales for the writing requirement? What kinds of contracts have to be reduced to writing or evidenced in writing? What counts as ‘some memorandum or note…in writing…signed by the party to be charged therewith’? What is the effect of non-compliance with the Statute of Frauds?; What is part performance? When can one seek a quantum meruit and why? ____________________________________________________________________________________ A. Why do certain kinds of contracts have to be reduced to writing or evidenced by writing? • Due to S/F, Sale of Goods Act, Guarantees Acknowledgment Act B. Rationales for the writing requirement C. What kinds of contracts have to be reduced to writing or evidenced by writing? • s. 4 of the Statute of Frauds. From a commercial perspective, note especially: 1. contracts for the sale of land or any interest concerning them (Deglman v. Guaranty Trust; Thompson v. Guaranty Trust) 2. contracts not to be performed within a year 2 *Rule in Adams v. Union Cinema: contract only has to be in writing if its performance of necessity must last longer than 1 year. *Rule in Hanau v. Ehrlich: If there is no mention of time and time is uncertain or indefinite, the agreement is not within the statute. Example #1: Alexi Yashin enters into an oral, 3 year, no-cut contract with the Edmonton Oilers in March. The next month, the Oilers cut him. Query: What is Yashin’s legal position now? Example #2: What about a lifetime oral contract of employment? It is enforceable? Example #3: Ms. X is hired by ABC law firm as a junior lawyer under an oral contract for an indefinite period at $8,000 a month. Both parties anticipate that the contract will last at least two years. After 3 months, Ms. X is fired without cause and without notice. Can she successfully sue? 3. A contract for the sale of any goods of the value of $50 or upwards Sale of Goods Act, R.S.A 2000,c. S-2, s. 6 Enforcement of contract over $50 6(1) A contract for the sale of any goods of the value of $50 or more is not enforceable by action (a) unless the buyer accepts part of the goods so sold and actually receives that part, or gives something in earnest to bind the contract or in part payment, or (b) unless some note or memorandum in writing of the contract is made and signed by the party to be charged or the party’s agent in that behalf. (2) This section applies to every contract referred to in subsection (1) notwithstanding that the goods may be intended to be delivered at some future time, or may not, at the time of the contract, be actually made, procured or provided or fit or ready for delivery or that some act may be requisite for the making or completing the goods or rendering the goods fit for delivery. (3) There is an acceptance of goods within the meaning of this section when the buyer does any act, in relation to the goods, that recognizes a pre-existing contract of sale whether there is an acceptance in performance of the contract or not. (note evidentiary substitutes that are not found in the original SF s. 4) 4. Contracts of Guarantee Guarantees Acknowledgement Act R.S.A. 2000, c. G-11 3 Requirements 3 No guarantee has any effect unless the person entering into the obligation (a) appears before a notary public, (b) acknowledges to the notary public that the person executed the guarantee, and (c) in the presence of the notary public signs a statement at the foot of the certificate of the notary public in the prescribed form. D. What counts as "some memorandum or note...in writing...signed by the party to be charged therewith"? 1. General comments based on CB it must adduce the existence of the contract and not fail for uncertainty. See McKenzie: need the 3 essential P's, namely parties, property, and price. But, per Tweddell, other essential terms might exist, as here, that payment of the purchase price was to be in stages. the document need not be intended as a memo of the contract. it is sufficient if the memo comes into existence anytime before the action is commenced. it can be constituted by several pieces of paper. it must be signed by the party against whom the contract is being alleged. E. mere initialing is sufficient hand-printed name is sufficient printed name of the contracting party on top of a standard form is sufficient (per McCamus) What is the effect of non-compliance with the S/F? 1. At common law Per Treitel: this failure does not make the contract void but only unenforceable. Per Riddell J.A.: “it must never be forgotten that the Statute of Frauds does not deal with the validity of the transaction, but only with the evidence to prove an agreement.” this means plaintiff has only a procedural problem wrt enforcement of the contract but the contract itself does exist. hence, per CB, the contract can be used by way of defence as in Barber and can also be used as consideration for a new contract and the like. 4 2. In equity Per Fridman: “it was decided quite early after the passage of the Statute, by courts of equity, that defendants would not be allowed to plead and rely upon the Statute if to permit them to do so would be to allow the Statute `to be used as an engine of fraud.'” Per Coyne J.A.: “Equitable principles which hold that the Statute of Frauds does not apply where there has been performance or part performance of the oral contract by, or where otherwise the result would be fraud against, or injustice to, the other party….” See F. below F. What is P/P? 1. Equity's desire to ensure S/F is not used as an engine of fraud is the foundation for the doctrine of P/P. 2. What counts as part performance? a. Lord Selbourne in Maddison v. Alderson seems to posit two views, per Fridman i. per Lord Selborne: the acts relied on “must be referred to the contract” [emphasis added] ACTUAL o This is the narrower view, per Fridman **Part performance must be ‘referable to the oral agreement that is relied on’, per court in McMillen v. Chapman. o This narrow view appears to have been followed in Deglman (S.C.C. 1954) by Rand J. while the broader view appears to have been followed by Cartwright J., according to the analysis offered by Erie Sand and Gravel Ltd. v. Seres’ Farms Ltd., 2009 ONCA 709 ii. per Lord Selborne: the acts relied on ‘must be unequivocally, and in their own nature, referable to SOME such agreement as that alleged.’ [emphasis added] o This is broader view, per Fridman 5 o See related analysis by MacDonald J. in Toombs v. Mueller: The broader doctrine is stated in Spry's Equitable Remedies, 1st ed. (1971), at pp. 244-5, where it is said: ... if the possession of land is delivered up in circumstances which are consistent, not only with the existence of a contract of sale, but also with the existence of a contract of lease, or of assignment, or of settlement, or indeed any other contract relating to the obtaining of a proprietary, possessory or other interest in that land, it will ordinarily be open to the plaintiff to establish any contract which falls within this wide general class. Accordingly, if once a contract of the general class of that actually entered into is sufficiently pointed to, the actual terms of the contract may be proved ... [emphasis added] o Per Upjohn L.J.: “acts need not be referable to no other title than the one alleged. They need only ‘prove the existence of some contract, and are consistent with the contract alleged.’” o This broader view appears to be the one followed in Thompson (SCC 1974). SCC in Thompson says that its decision in Brownscombe stands for the proposition that the performance has to be plainly referable to an agreement as to the very land. o Sask C.A. in Lensen discusses the theoretical foundation of the doctrine of P/P: i. orthodox account: “alternative evidence” – acts of P/P are seen as evidence sufficiently cogent of the contract to permit equity to enforce it. Leads to a more narrow test of P/P ii. modern account: “raising equities” - acts of P/P raise equities in the plaintiff’s favour which render it unjust not to enforce the contract, per Steadman. Leads to a broader test of P/P. o Test in Canada is not yet clear. G. When can one seek a quantum meruit and why? *see Deglman 6 f:\formalities statute of frauds intro1..docx