Philippines: US 'rebalance' brings prosperity, security to the region

advertisement

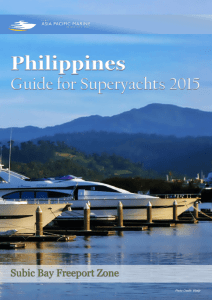

O C About this project ← Tilting the balance of power: Oil flows to the East The Team Conclusions about U.S. energy security → Philippines: US ‘rebalance’ brings prosperity, security to the region By David Kashi and Kevin Wang | No Comments SUBIC BAY, PHILIPPINES – Twenty years after the U.S. Navy closed one of its largest overseas bases here, Vic Vizcocho watched the USNS Charles Drew pull into the busy shipyard and marveled at the return of American maritime traffic. The longtime local resident hopes the ships will bring a return to “good jobs, good pay, great work ethics and business opportunities everywhere.” But he and other residents also hope the bulked-up American naval presence will ensure peace in the hotly South China Sea with its rich energy resources. The steady increase in U.S. Navy ship visits accompanied by joint military ex ercises hosted in the area signal a major shift in resources as the United States winds down wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and aims to secure its national security interests in the Pacific. In Subic Bay, on the west coast of the Philippines’ largest island, the U.S. military is trying to protect a vast store of largely untapped energy reserves from being monopolized by China or any other country. National security and energy ex perts say that though the South China Sea is not a significant energy ex porting region fore the U.S., it has vital strategic importance for America’s energy security, especially the freedom of energy shipping routes. Tensions in the South China Sea The South China Sea is the site of frequent territorial disputes as nations battle for the oil and gas resources hidden beneath its calm waters. Backed by a stronger military and a more confident regime, CNOOC – China’s third largest national oil company – is aggressively claiming ex ploration rights in the South China Sea, some of which are also claimed by neighboring countries. According to a report from the RAND Corporation, China’s recent assertiveness in the South China Seas pose a potential military threat to the U.S. and its allies, who have a big stake in maintaining open sea lanes to receive a continuous flow of oil from the Persian Gulf. open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Asia’s rapid economic growth, driven primarily by the region’s leading emerging economies like India and China, is creating a surge in demand for energy resources. A report released by the National Bureau of Asian Research in September called Asia “ground zero” for growth in global energy and commodity markets, indicating that the region will account for more than 85 percent of the world’s increase in demand for oil over the nex t 20 years. Almost all claimants of the South China Sea depend heavily on imported oil due to lack of domestic production capacity, and the unstable oil-producing regimes in the Persian Gulf have forced them to look elsewhere for future supplies. The South China Sea, stretching from the Strait of Malacca to the Strait of Taiwan, is a perfect alternative. Energy ex perts in the region say it contains rich hydrocarbons, especially oil and natural gas. W hile natural gas may be the most abundant resource in the South China Sea, the oil reserves are estimated as high as 213 billion barrels, equivalent of about 80 percent of those of the Saudi Arabia. Countries in the region such as China, Vietnam and the Philippines are competitively bidding for ex ploration rights, but most of their national oil companies lack necessary drilling capacities to reach the deep-sea reserves. But where there is opportunity, there is also conflict. Ever since the 1970s, when oil and gas reserves were first discovered, the South China Sea has been a simmering point of contention. And in recent years, it has erupted into a full-fledged conflict. Neighboring countries including China, Vietnam and the Philippines have laid claim to these waters and their resources. W ithin the area, the Spratly and Paracel islands are among the most disputed spots, leading to major armed clashes in recent decades that show no signs of stopping. The U.S. Energy Information Administration estimates that as Asia’s demand for oil continues to rise rapidly, these conflicts will intensify. The conflicts provide a complicated challenge to the United States, a Pacific power for 70 years. W hile many allies and partners are relying on the U.S. to protect their rights to ex plore the oil and gas, America also has an interest in maintaining regional stability and freedom of navigation without directly antagonizing China. Complicating matters are the facts that there is no collective code of conduct and that China claims the entire South China Sea based on its historic records. Meanwhile China is increasing its military spending, modernizing its Navy and acquiring advanced maritime capabilities. In recent years, China has developed new strategies including plans to ex pand its naval presence to the Indian Ocean, an area where U.S. Navy currently dominates. Historically, China’s military priority has been defending territorial rights with a special focus on Taiwan. However, the Pentagon said its investment in platforms such as nuclear-powered submarines and its first aircraft carrier suggest China seeking to support additional military missions beyond its borders. America’s Pivot to the Pacific, and a potential Dragon-Eagle fight In his trip to Australia in November 2011, President Barack Obama announced a major new security initiative aimed at shifting the open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com focus of U.S. attention—military and otherwise —to the Asia-Pacific region. “As we end today’s wars, I have directed my national security team to make our presence and mission in the Asia Pacific a top priority,” Obama said in a speech before the Australian parliament. “The United States will play a larger and longterm role in shaping this region (Asia-Pacific) and its future.” The so-called “Asia pivot’” aims to promote U.S. interests by helping to shape the norms and rules among regional players so no single country poses a threat to the stability and freedom of navigation, and to ensure that international laws are respected and that no country is under the coercion of another, said Thomas Donilon, Obama’s national security Picture 1 of 20 ◄ Back Next ► Blessed by its sheltered harbor and proximity to major shipping routes, the Philippine’s Subic Bay is key to regional economic activities and energy security. David Kashi/MNSJI adviser, in a speech at the Center for Strategic and International Studies on Nov. 15, 2012. Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said 60 percent of U.S. naval assets will be based in the Pacific by 2020 – a historic high. That includes a net increase of one aircraft carrier, four destroyers, three Zumwalt destroyers, 10t littoral combat ships and two submarines. That, Panetta said at last June’s Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, “will provide our forces with freedom of maneuver in areas in which our access and freedom of action may be threatened.” Already, the Pentagon has announced new Marine rotational deployments to Australia, new littoral combat ships, and the possibility of closer military cooperation with the Philippines. “I think our interest is purely driven by our economic security,” said retired Marine Corps Lt. Gen. Richard Zilmer, “and we must have a strong economy in order to have a strong national security posture.” Zilmer said the “Asia Pivot” can help by securing regional sea lanes for oil and commerce. open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Freedom of navigation in the W estern Pacific is also a big concern for China. According to the Pentagon, in 2010 more than 80 percent of China’s oil imports transited the South China Sea and the Strait of Malacca. “The sheer volume of oil and liquefied natural gas imports to China from the Middle East will make strategic sea lines of communication increasingly important to Beijing,” the Pentagon said in its annual report to Congress in 2011. W ith China already importing 60 percent of its oil and gas and predicted to import almost 75 percent by 2030, Liu Feng, a research fellow at China’s National Institute for South China Sea Studies, said access to reserves in the South China Sea is crucial in fueling the country’s rapid growth in the nex t 50 years. “America thinks that with its intervention, the current power imbalance between China and the rest can be resolved,” Liu said, “Instead, it will only make the situation worse.” Although the U.S. has downplayed potential conflicts with China in the region, many see a rivalry inevitable between the world’s only superpower and an emerging power. Some analysts and military officials in Beijing call the shifting American military posture a clear threat to China’s internal affairs and territorial sovereignty. “China now faces a whole pack of aggressive neighbors headed by Vietnam and the Philippines and also a set of menacing challengers headed by the United States, forming their encirclement (a military term describing a situation when a force is surrounded by enemies) from outside the region,” wrote Xu Zhirong, a deputy chief captain with China Marine Surveillance, in the June-2012 edition of China Eye, a publication of the Hong Kong-based China Energy Fund Committee. “And, such a band of eager lackeys is ex actly what the U.S. needs for its strategic return to Asia,” he wrote. An increase in U.S. military activities Vizcocho, a local newspaper publisher who used to work for the U.S. Navy, said that he has seen lots of military activity around the Freeport Zone and nearby air station across the harbor lately, and that the tempo is picking up fast. Subic Bay has been a major strategic site for U.S. Navy’s logistical support and repair facilities since W orld W ar II, but the base was forced to close in 1992 due to rising Philippine nationalism and the eruption of the nearby Mt. Pinatubo volcano. The Subic Bay Freeport Zone, a massive hub of $8.8 billion in foreign investments, more than 90,000 jobs and some 1,500 businesses now is a key regional gateway. Located in the W estern Pacific near important water crossroad Strait of Malacca, Subic Bay usually serves as the place for U.S. logistics ships to repair and refuel. W hen U.S. aircraft carriers move between bases on the U.S. W est Coast, and the Persian Gulf, they sometimes visit Subic Bay or nearby Manila Bay, which has larger capacity. On Oct. 5, 2012, thousands of sailors and U.S. marines aboard amphibious assault ship USS Bonhomme Richard arrived in Subic Bay just days before the annual U.S.-Philippines amphibious landing ex ercise, in which U.S. and Philippine marines had a combined training with the Armed Forces of the Philippines focusing on humanitarian assistance and natural disaster response drills. open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Philippines focusing on humanitarian assistance and natural disaster response drills. Three weeks later, the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS George W ashington visited Manila Bay for a five-day goodwill visit.. On Nov. 26, the Charles Drew pulled into Subic Bay for a two-day stop. Future: rotational places, not permanent bases American forces are indeed coming back, but in a different fashion this time. In the future, the Pentagon will add rotation deployments to Asia Pacific instead of having long-tern installations. Both Air Force and Navy are looking at increased presence in northern Australia, while the Marine Corps is planning to deploy 2,500 troops on a rotational training basis. Pentagon officials say, in the future, U.S. may use Subic Bay for port visits instead of long-term bases. U.S. Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Jonathan Greenert ex plained last November at an event in W ashington DC, the Navy will have rotational deployments to the Asia-Pacific region, rather than permanent bases. The U.S. is in talks with allies and partners that will allow US forces to access places in the region so it can continue to operate there and remain a Pacific power. “Additional bases in the Pacific are not being sought by the U.S., but the Philippines has offered increased port visits to Subic Bay,” said Bernard Cole, a retired U.S. Navy captain who teaches at the National W ar College. Cole ex pected more Navy visits and the possible establishment of a repair facility manned by civilians. U.S. officials are now in talks with Philippine defense and diplomatic officials to increase the frequency of joint military ex ercises, ship and aircraft visits and other types of cooperation. Panetta’s visit to the naval and air base at Cam Ranh Bay in Vietnam in early June opened the talks about allowing the U.S. Navy to reuse the country’s deep-water port. Local voice: U.S. comeback is necessary Twenty years ago, as a result of surging nationalism, lawmakers in the Philippines Senate voted to terminate the lease on U.S. military bases in the country. Today, many see the U.S. rebalance to the region as a positive move. For local Filipinos in Subic Bay, the comeback of U.S. and its military presence means more economic opportunities. But more importantly, it brings a sense of security. “It’s only right to maintain a balance of power,” said Edgar G. Geniza, president of Mondriaan Aura College in the Freeport Zone. “The U.S. presence will remind big countries to go slow and not forget about the responsibilities to their fellows.” “Personally, I think it’s better for us. W e feel a little more secure when Americans are around,” Geniza added. “W e realize we are not as strong as some other powers in the region. In terms of our Air Force, we have more air than force.” open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Added Renato De Castro, an international studies professor at De La Salle University in Manila, “W e are faced with what we perceive as China growing more powerful, more assertive, [so] we simply have no choice but to rely on the offshore balancing role of the United States. This is a situation that we don’t like, but have to do, simply because we are faced with an emergent and certainly confident great power.” Olongapo City Mayor James “Bong” Gordon, a strong supporter of more U.S. military presence, has been to countries like Singapore and Guam to lobby for stronger regional alliances with the U.S. He linked the region’s economic security to national security. “W e want a secured region,” said Gordon, “To secure the region, we want to host our military allies. W e need the U.S. military to be the deterrent for the Southeast Asia region, and to patrol the waters. The Philippines cannot do it alone.” ← Tilting the balance of power: Oil flows to the East Conclusions about U.S. energy security → Copyright © 2014 Medill National Security Journalism Initiative open in browser PRO version Are you a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com