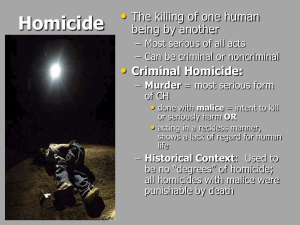

homicide: murder and involuntary manslaughter

advertisement