A population Health Primer[1].

![A population Health Primer[1].](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008316909_1-cf1c23d1a8566cc8f234d7a707743ccb-768x994.png)

the northern way of caring

Visit us online: www.northernhealth.ca

IMAGINE that!

You

can

use a population health approach in your planning, programs and practice!

A Population Health Primer for Northern Health

By Theresa Healy & Julie Kerr, Population Health

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER…

Investing upstream and for the long haul

Multiple, strength based strategies

Addressing the determinants of health

Grassroots engagement

Intersectoral collaboration

Nurturing healthy public policy

Evidence based decision making

“We are members of a great body.

We must consider that we were born for the

good of the whole.” Seneca. 4BC—65AD

Produced by:

©Population Health, Northern Health

Centre for Healthy Living

1788 Diefenbaker Drive

Prince George, BC V2N 4V7

Phone 250.565.7390• Fax 250.565.2144

Theresa Healy and Julie Kerr

Contact us at: theresa.healy@northernhealth.ca julie.kerr@northernhealth.ca

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

IMAGINE: An Introduction to Population Health Principles......3

The determinants of health ..................................5

Investing upstream and for the long haul .........................7

Tools for thought: Ripple in the Pond ......................8

Multiple, strength based strategies ................................9

Tools for thought: Selecting the right tools .............. 1

0

Addressing the determinants of health .......................... 11

Tools for thought: DOH Review............................. 12

Grassroots Engagement ............................................ 13

Tools for thought: Sociogram ............................... 14

Intersectoral collaboration ........................................ 15

Tools for thought: Understanding Partnership ........... 16

Nurturing healthy public policy ................................... 17

Tools for thought: Identifying Policy Opportunities ..... 18

Evidence based decision making .................................. 19

Tools for thought: Literature review ...................... 20

Weaving it all together ............................................. 21

Tools for thought:

Population Health Check List ........ 22

Resources consulted ................................................ 23

Back page - Contact information ................................ 25

Acknowledgements

We want to acknowledge that we stand on the shoulders of giants in producing this work. Dr

Lorna Medd, Dr. David

Bowering, and Ms. Joanne

Bays were all involved in the brainstorming sessions that developed the IMAGINE acronym. Many other colleagues and friends have contributed insights, work and ideas to this primer.

Many community activists and champions have lived and breathed this work in the practical laboratory of everyday life. To all of these supporters we offer our

sincere thanks.

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 3

U

C

O

D

T

R

I

N

T

I

O

N

IMAGINE: An Introduction to Population Health

Principles

A challenge to think and act differently in how we approach health care issues and services

We use the word IMAGINE to remind us of the seven major principled activities of population health:

Invest upstream and for the long haul; use

Multiple, strength-based strategies;

Address the determinants of health; garner

Grassroots engagement; lead

Intersectoral collaboration;

Nurture healthy public policy; employ

Evidence based decision making.

We also view it as a call to action for all of us who envision a healthier future to articulate and work for the healthy communities that are the foundation of a well society.

Northern Health is leading a new edge of thinking and practice in adopting a population health approach as one of the four pillars in its strategic plan looking to 2015. This primer is designed to introduce NH practitioners to the basic concepts of population health as our Population Health and

Healthy Community Development programs conceive and apply them. Currently under development are two sequels.

The next primer will introduce stories of success from NH practice as examples of IMAGINE in action, or IMAGINE-

action, so to speak. The third primer will seek to demystify the use of research and evaluation as we purpose to continuously improve the effectiveness of our service delivery from a population health perspective, using the IMAGINE principles.

Canada has long been a world leader in the field of population health beginning with Jake Epp’s work, the Ottawa Charter, and Alma Alta. There is a long standing and honorable history of involvement in the improvement of living conditions that directly impact the health and wellbeing of members of

Population health is the theory and practice of improving the health of groups of people rather than of individuals. society. This longstanding concern with uncovering the links between poverty and disease sees a need for health organizations to champion social justice efforts and to have an impact on the broader determinants of health. This has led to improved health and well being for a wide segment of the population. In fact, it has been argued that more lives have been saved because of advances in this area than in any other branch of medicine.

Dr. David Butler Jones, Canada’s first National Public Health

Officer, has identified an “aligning of a constellation of factors that promises a brighter future for those working in population health. Reports and discussion papers from the

World Health Organization, the Conference Board of Canada and the Health Officers Council of BC, related to the underlying determinants of health, were released within weeks of each other in the fall of 2008 and have received broad media and political attention.

This growing interest in the broader determinants of health is an opportunity to embrace population health and integrate it into the core activities of the health care sector. The challenge is for front line health care providers, community health activists and policy makers to understand and champion population health principles and practices as preferred practice. This primer is a beginner tool to set you on this exciting journey.

Population health is a relatively new term that has not yet been precisely defined. Is it a concept of health or a field of study of health determinants? We propose that the definition be “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group,” and we argue that the field of population health includes health outcomes, patterns of health determinants, and policies and interventions that link these two. We present a rationale for this definition and note its differentiation from public health, health promotion, and social epidemiology. We invite critiques and discussion that may lead to some consensus on this emerging concept. (American Journal of Public Health.

2003;93: 380–383)

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 4

Figure 1: Nancy Hamilton and Tariq Bhatti, Health Promotion

Development Division, Health Canada, Feb. 1996

Key questions to ask: What are the causes of poor health? How do we address those causes before they lead to health problems?

The issues that population health addresses are critical in BC.

While averages suggest that the BC population, in general, is enjoying improving health status, the averages conceal - as the

Provincial Health Officer’s report states - some very dangerous inequities:

While on the whole, British Columbians are among the healthiest people in the world, there is a relatively large number of disadvantaged people in the province – the unemployed and working poor, children and families living in poverty, people with addictions and/or mental illness,

Aboriginal people, new immigrants, the homeless, and others – all of whom experience significantly lower levels of health than the average British Columbian. In fact, BC has the highest rates of poverty (particularly child poverty) in Canada. This presents a paradox: despite having, by some measures, the best overall health outcomes in

Canada, BC also has the highest rates of socioeconomic disadvantage in the country.

Since the 1990s, British Columbia has employed the innovative and well tested Healthy Communities methodology as a way to redress health inequities, and the province has recently revived the model.

Provincially, there are multiple networks, councils, initiatives and programs aimed at reducing health inequities and improving health outcomes for all. The province’s decision to include public health as a core program has been matched in Northern Health by the inclusion of population health as one of the four pillars of Northern

Health's strategic plan looking to 2015.

“I am in public health because I am an optimist. And I think there are reasons for that optimism. We have never had such a constellation coming together as we have right now in recognizing the interconnectivity of these (social determinants of health) issues and that we can’t do it alone… Given the economic challenges we are facing, that spirit of cooperation and collaboration, the skills we have in those areas, are even more necessary.” Dr, David Butler-

Jones, Dec 2nd presentation to the Public Health Association of BC (PHABC), Dec 2, 2008

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 5

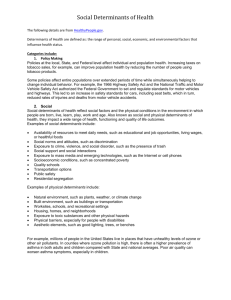

The determinants of health

The determinants of health are those factors in our daily lives that directly and indirectly impact the state of health we can enjoy. Dennis Rapheal argues that the determinants of health are, “in a nutshell, about how a society chooses to distribute resources.” (from a lecture for Nursing 5190, The Politics of

Population Health http://msl.stream.yorku.ca/mediasite/ viewer/?peid=ac604170-9ccc-4268-a1af-9a9e04b28e1d ). While we need to address ill health, we also have to address the underlying causes of ill health. It makes more sense, morally, physically, financially and emotionally to prevent disease than to struggle to cope with the effects of disease and sickness upon individuals, families and communities. Figure 2, below, illustrates the interconnected nature of these influencing factors.

In essence, the determinants of health lay out the range of possible factors that influence how healthy we will be: genetic predispositions, lifestyle choices, opportunities and

Figure 2: Factors that influence our health, as found in The Report on the

State of Public Health In Canada, 2008. Dahlgreen & Whitehead, European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: Leveling up Part 2, World

Health Organization, 2006 challenges that enhance or limit quality of life and ultimately impact on health outcomes. Some, particularly the genetic or biological ones, are limits that we have little control over, for better or for worse. Others we can—and should—try to reverse. But research clearly demonstrates that individual behaviour change is difficult to achieve unless a combination of education, legislation and enforcement is mobilized in the society at large to make healthy choices possible, socially acceptable, and easy. It requires political will and a collective commitment to addressing the needs of the most disadvantaged, to improving early childhood development opportunities and education for all, to facilitating stronger networks of support and creating a truly inclusive society.

Health inequities are differences in health status experienced by various individuals or groups in society. These can be the result of genetic and biological factors, choices made, or by chance; but often they are because of unequal access to key factors that influence health, like income, education, employment and social supports. The State of Public Health

in Canada 2008. p3

Exercise

Diet

Tobacco

Poverty

Isolation

Housing

Literacy

Racism

Addictions

Mental Health

Colonization

Abuse

What lies beneath

The tip of the iceberg, we can see and measure and direct people to change; individual focus

Beneath the surface are the things that impact and influence lifestyle, choices and capacities of change we can see and measure and direct people to change; needs a collective focus. Higher levels are barriers to be addressed. The deeper we go, the more complex and difficult the issues

Adapted from R.A. Dovell,

Population Health

Confernece 2002

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 6

Inequities are killing people on a "grand

scale" reports WHO's Commission:

"(The) toxic combination of bad policies, economics, and politics is, in large measure, responsible for the fact that a majority of people in the world do not enjoy the good health that is biologically possible," the Commissioners write in Closing the Gap in a

Generation: Health Equity through Action on the

Social Determinants of Health, 2008.

The impacts of the determinants of health demonstrate that there are two types of health status. One is acquired through hereditary means – including class and status, while the other derives from environmental conditions. As

Romanow’s advice famously states, there is a sure fire recipe to acquire and sustain good health. (see figure 3 below)

In summary

• Canada has a commitment to and is a leader in recognizing the complex interdependencies of the determinants of health on the potential well being and health of populations.

• British Columbia has been making important changes at the policy level which support the work of population health.

• Northern Health has adopted population health as one of four pillars in its strategic plan.

• Taken together, the signs point to a need to be familiar with and actively apply the principles of population health as a way to redress health inequity and ensure scarce resources are put to their best use.

“The Minister of Finance can choose what level of poverty we will live with.”

M.Marmot, 2008

Figure 5: Text and illustration from Social Determinants of Health in Canada, presentation by Elizabeth Gyorfi-Dyke, CHPA, 2005

I

Investing upstream, for the long haul

“ Ultimately, health is political; it is the allocation of resources that has the greatest impact on health.” Helena Bryant

Investing upstream and for the long haul refers to the necessity of looking beyond the immediate acute care focused model of health care service. While there is no denying the importance of providing a system of care to those who are sick, the reality is that “if we build it they will come.”

Planning for and resourcing thousands of acute care beds assumes and prepares for an ailing population, while investing significant time, energy, expertise and money into preventative health would decrease the need for those beds substantially.

Population health is a key approach for building a more sustainable health care system that proactively supports wellness while maintaining a contingency plan to treat illnesses. The BC Public Health Association has proposed that the provincial government adopt a “6% solution,” which would mean a doubling of the current investment of 3% of the total health care budget currently being spent on health promotion and disease prevention. This would require all health authorities to reallocate a small portion of their budgets and make a deliberate increased investment in public health initiatives. It would force us to ask ourselves some challenging questions about our existing practices. What could we stop doing? What could we take a break from doing?

How can we deliver needed downstream services more efficiently to free up resources for prevention efforts? As we experience financial savings that result from more effective prevention work, where should those dollars be reinvested?

What will give us the biggest population health outcome bang for our limited bucks?

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 7

Northern Health’s mission, vision, values and principles overtly support us in asking these questions. Furthermore, there are people within Northern Health that have been trained as internal experts to assist us in reviewing our services and programs in this way. There are processes that have been developed within the business sector that are now being applied to health care settings as population health planning tools. PBMA and Lean are two such methodologies that have been adopted within

Northern Health and there are people and practical tools available to assist managers, leaders and teams in applying these methods to their service planning and evaluation (See next page for more detail). Albert Einstein said that the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result. The time has come for us to think and act in a radically different manner as we plan and deliver our services.

The most challenging part about allocating more resources upstream is proving that the reallocation has had a significant positive outcome on health. It is much easier to count numbers of people with illnesses and report on service utilization than it is to demonstrate that fewer services were required and people did not get an injury or disease.

Evidence of population health outcomes takes upwards of 20-

30 years to accumulate, especially since the preventive measures taken in early childhood have the largest impact on health in the adult years.

An example of this was encountered in a First Nation in the northeast recently, when a Spectra Energy employee pointed out that a Head Start early childhood development program started on a reserve 30 years ago has resulted in a thriving young workforce in that community today. Because youth in this community have completed high school, avoided addictions and remained healthy into young adulthood, they are now able to earn a good, secure income, provide an increasingly high quality of life for their families and break the cycle of poverty. The positive impacts are being felt within the First Nation, the energy sector, in reduced unemployment rates, and in decreased negative outcomes for the entire area.

Marc Lalonde’s work in New Perspectives on the Health of

Canadians envisioned a balance between investing in the

"upstream" of public

"downstream" health and illness prevention as well as in the of health care delivery.

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 8

PBM-what?!?!?!

Due to resource scarcity, health organizations worldwide must decide what services to fund and, conversely, what services been not to fund. One approach to priority setting, which has widely used in Britain, Australia, New Zealand and Canada, is program budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) .

To date, such activity has primarily been based at a micro level, within programs of care.

Health Serv Manage Res 2005;18:100-108 doi:10.1258/0951484053723117

© 2005 Royal Society of Medicine Press

Lean - it might not be what you think!

Lean isn’t about being skinny; lean is not “mean.”

Lean does not mean cutting staff in the name of cutting costs (see “lean is not mean”). “Lean” is the set of management principles based on the

Toyota Production System (TPS). Lean has been applied in manufacturing, as well as in service industries. Lean has 2 essential components:

1. Eliminate waste and non-value-added (NVA) activity

2. Have respect for people

Tools for thought: Ripple in the Pond

Imagine an intervention of your program as a pebble tossed in a pond. Visualise where the ripples have the potential to reach.

Describe the intervention

Who (or what) will be impacted first?

What are the secondary impacts?

Identify more remote impacts or “trickle down” effects

If

you want to learn more about these and other quality improvement tools that may help you to plan upstream interventions, contact NH’s Corporate Planning team.

Now, with an objective, constructively critical eye, consider whether the impacts of the intervention you are analyzing are more upstream/preventative in nature or more downstream/ reactive. Is your intervention decreasing the likelihood of health problems, or is it treating an injury or illness after the fact? Is there another intervention you could be undertaking that would have more upstream impacts? Should this be done instead of what you’re doing, or in addition to it?

M

Multiple, strength based strategies

Looking for more than one tool and method and focusing on strengths increases the for intervention.

Working with communities is not easy.

The human factor means work always takes longer than planned and that process issues are as important as content. Neglecting process almost always guarantees problems. Thus, having an array of tools in your toolbox for population health work is a necessity.

This section of the primer is a brief orientation to some of the most effective tools in the world of community development and organizational change. They lend themselves very well to the community capacity building work that is the heart and spirit of population health. There is also a list of hyperlinks that will take you to a major resource for each one.

Appreciative Enquiry

Appreciative Enquiry is a foundational approach that asks how we can enter the worlds of other people with our desire to support positive change. Appreciative Enquiry argues that change begins the moment we start asking questions. There is a vast difference between “What’s wrong with your community?”, which is likely to elicit a litany of complaints and negative feelings about one’s home town and “What do you like about your community?”, which allows people to focus on those positive attributes that contribute to resiliency and commitment. In terms of respect and engagement, entering communities and asking what they value, rather than arriving armed with data about what’s wrong and what must be changed, will receive a warmer reception. Appreciative

Enquiry provides a respectful and strength focused platform on which to open the dialogues that communities need to undertake to identify for themselves the issues they deem important. Interestingly, Appreciative Enquiry requires the

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 9 major shift to come first from within the practitioner, not the community. For more in depth discussion, see http://www.appreciativeinquiry.org/

World Café

World Café is a community consultation method that encourages groups of people to engage in deep and meaningful conversation. It spells out a process and format that supports exploration and discovery. In light of the speed at which the world is changing and the intrusion of technology into human communication, World Café lays out what we need to communicate face to face more effectively. It relies on our innate human desire to relate, learn and understand and the universal familiarity of a café table. Skilled facilitators engage minds while table top toys and art supplies engage hands and creatively ensure that the outcomes of

World Café discussions are fruitful and inspiring, even among strangers.

Visit: www.theworldcafe.com and see also The World Café: Shaping

Our Futures Through Conversations That Matter by Juanita Brown and

David Isaacs with the World Café Community; Forward by Meg

Wheatley, Afterword by Peter Senge

Open Space

Created by Harrison Owen, who observed that his most meaningful education at conferences and workshops happened during coffee and meal times, this process calls on people to be self organizing. The agenda for the work is created from the passions and interests of those present in the room. Experienced initially by some participants as uncomfortable, the Open Space quickly becomes an energizing and dynamic process that can be highly productive. It requires a skilled facilitator and non-traditional facilitation techniques. The process asks participants to nominate topics for discussion; the nominator then becomes the host for that discussion. The underlying principle is that personal passion implies responsibility and may often provoke conflict.

An important tenet is to see conflict not as something to be avoided but something to be welcomed and handled well as a companion of passion. With only four principles and one rule, Open Space supports individual initiative and collective creation. See: http:// www.openspaceworld.org/

“Turn your face to the sun and the shadows fall behind you.”

Maori proverb

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 10

Community Development; Community Capacity Building;

Capability Approaches; Integral Capacity Building Framework

These terms refer to a broad range of methods and approaches that conceive of communities and their members as vital participants in the successful working of population health. The Quick Links resource section on page 25 of this primer includes a list of reliable sources to check out for more information and new developments in each of these dynamic approaches.

Briefing workshop

An amazingly simple way to get a group to cycle through the major stages of a research project in a short time with immediate and useful data and feedback.

Word clouds

Wordle is an easy to use web based tool. You enter a list of words generated by a group on a topic or pick words out of a website or article. The resulting artistic presentation is also a visual representation of what is important. See www.wordle.net

A word cloud generated from the IMAGINE acronym and principles using the tool found at www.wordle.net

Tools for thought: Selecting the right tools from your tool box

The methods that you can choose from as tools to help develop multiple, strength based approaches are many. Each will contribute different supports in different ways. You need to be aware of limiting and facilitative factors that can determine which tool is the best for your task at hand. The following check list should help you determine what will work best for you.

1. What sort of process are you looking at? Do you want to gather information or develop a team? If you are gathering information, what sort of data are you after?

Some methods can multitask and contribute to more than one outcome.

2. Who are you working with? If it is a group struggling with literacy issues or a group that is suspicious of your organization, you will need to adopt non-written approaches for the first group and devote time to relationship building with the second.

3. Who is the intended audience for the results? The validity and credibility of the tools you choose will be assessed differently by different audiences. A community group may value the stories and hearing their own voices and concerns resonating in the data. A funding body may want more numerical and statistical information.

Some key questions to think about:

What do I want to get from the strategies I use?

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

Who will I be working with?

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

Who is the audience?

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

What are some facilitators I can rely on? What are some potential barriers I can anticipate and prepare for?

_____________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________

A

Addressing health determinants

Addressing the determinants of health requires a shift in thinking for many of us in the health care field.

Rather than focusing on the person in front of us, their symptoms and needs, we step back to consider the context within which the person lives, demographic trends and clusters of health concerns emerging in our region.

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 11

The factors and elements in a person’s life influence or determine how healthy they can be. If we improve these factors, we can improve health status and health care outcomes. The Canadian Population Health Initiative estimated that personal lifestyle factors have a very strong or strong impact on the health of Canadians: a person’s eating habits (72%), amount of exercise a person gets (65%), whether a person smokes (80%). At the same time, the broader

determinants affect one in three Canadians, who report social and economic conditions (a person’s level of income –

33%; availability of quality housing –34%; a person’s level of education—33%; safety of communities—35%) influenced the health of Canadians (CPHI, 2005).

The World Health Organization argues that prevention of the chronic diseases that are increasing globally is best achieved by acknowledging misconceptions, such as that chronic diseases affect only the wealthy and the aged and are expensive and problematic to address. As Dr. Butler-Jones notes in the Chief Public Health Officer’s Report for 2008

CPHO report:

As we strive to achieve good health for as long as possible, it is important to note that, while some health challenges can be related to our genetic make-up, evidence shows that Canadians with adequate shelter, a safe and secure food supply, access to education, employment and sufficient income for basic needs adopt healthier behaviours and have better health. (The Chief Public

Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in

Canada 2008: Helping Canadians achieve the best health

possible p.3)

Addressing the determinants of health requires understanding:

1) How these determinants impact the potential of individuals, families and communities to understand the implications of issues to their health, 2) The constraints and limitations that inhibit participation or involvement in health promotion activities, and 3) The ingenuity required to develop alternatives to reduce the impact of those constraints.

The necessary creativity and innovation is grounded in the vital expertise of front line practitioners. However, to move innovative and promising initiatives developed by frontline practitioners into sustainable and broad ranging practice, beyond the working life span of particular individuals, requires the development of policies and enforcement structures that ensure organizational commitment to emerging best practices. Policies can and should be developed within the health authority for each of the social and environmental determinants (omitting biology and genetics).

Many examples of such policies and practices operate in ad hoc or issue specific ways (such as social support initiatives within mental health, for example, or peer support groups for those struggling with addictions). Such program initiatives have direct and meaningful lessons for program policies. The challenge for practitioners is to broaden the impact of such innovations beyond specific program areas and make them foundational to all the services we deliver.

We know what makes us ill.

When we are ill we are told

That it’s you who will heal us.

When we come to you

Our rags are torn off us

And you listen all over our naked body.

As to the cause of our illness

One glance at our rags would

Tell you more.

It is the same cause that wears out

Our bodies and our clothes.

Bertolt Brecht, A Worker’s Speech to a Doctor, 1938.

Quoted by Dennis Raphael, Social Determinants of Health:

Why is There Such a Gap Between Our Knowledge and Its

Implementation?

Ryerson, Toronto, 2002

Examples of policies that address income and social status might include income support; incentive and subsidy commitments; partnerships in developing safe, affordable housing alternatives; including provision of healthy snacks and refreshments at programs such as immunization clinics or educational workshops; alternative communication and outreach strategies that address trust and social alienation issues; readiness assessments and support to ensure cultural and social respect. Improving social support networks might include peer support and family support training network development. It is clear that such initiatives toward addressing the determinants of health and reducing inequities could have quite direct health impacts, for example, by reducing youth suicide rates in a community. A multitude of indirect impacts may also occur, as depicted in the complexity model below.

Social

Structures

Work

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 12

Material

Conditions

Social

Environment

Psychological

Brain

Neuroendocrinal and immune response

Health

Behaviours

Early life

Pathophysiological and organ impairment

Genetics

Culture

Well being and mortality

Mortality

Morbidity

F igure 3: Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Pamuk ER, et al. (1998) Income inequality and mortality in metropolitan areas of the United States.Am J Public Health. 88: 1074-1080 .

Tools for Thought: Your Health

Determinants Review

Consider the population you serve. Which of the health determinants can you identify as key in their lives?

Prioritize them and then consider in what ways your program and services can address them. For example, if your first determinant was poverty, you may be able to advocate for free entry to programs, offer nutritious snacks with programs, develop income supplement options, transportation, etc.

Determinant #1: ___________________________________

Ways to impact this: ________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Determinant #2:____________________________________

Ways to impact this: ________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Determinant #3: ___________________________________

Ways to impact this: ________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

Determinant #4: __________________________________

Ways to impact this: ________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

__________________________________________________

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 13

G

Grassroots engagement

Grassroots engagement is the most critical component of a

successful

Research consistently shows us that,

across time and place, where people have a hand in shaping solutions, they are more committed to and involved in the success of those solutions.

Community engagement, for Northern Health, is the active mobilization of organized groups around the common goal of improving health. Engaged communities can support and sustain reforms, and disengaged communities can jeopardize them. Engagement is defined as:

...the mobilization of constituencies organized as groups and the meshing of constituency groups into an active relationship around a common mission, goal, or purpose… Such engagement, ultimately, results in a shared culture of action and mobilization in which participating groups are evaluated by what they do rather than by what they say. (Adapted from “ Engaging Communities”,

VUE Number 13, Fall 2006).

Community organizing

Grassroots community organizing has been long used as a civic engagement tool, particularly for disadvantaged or marginalized people, to gain influence over the social and political institutions and agencies that impact their lives. It has a longstanding and diverse history, from neighborhood based groups (e.g. Saul Alinksy) to the broader political activities of the civil rights movement. Community organizing is a process whereby people are brought together, acting in a common self-interest to achieve common aims. It is one of the basic tools for grassroots engagement.

Mobilizing populations

If we subscribe to Paulo Frieire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed concepts, we believe that people hold the keys, the solutions, to the challenging situations in their own lives. What they lack are the means to share their knowledge in constructive ways.

Lack of education, lack of self esteem, a sense of powerlessness, alienation from social and political supports all combine to convince people that they are not qualified or competent to act on their own behalf. Only experts, the highly educated, or governments are seen as the authorities who can and should act on issues. When the experts do act, however, and regardless of the best of their intentions and the high level of knowledge and expertise they bring, their efforts are ridiculed, fail or miss the mark, and no one is happy.

Finding the key: Personal Passion

Principles for meaningful engagement:

•

People must be able to share what they know about an issue in an atmosphere of respect

•

They must be encouraged to learn and grow and acquire new skills

•

They must be encouraged to translate their knowledge into effective actions to improve their own lives and health and the lives and health of their community

•

Opportunities to engage with tools for change, with each other and with the system must be regular and ongoing

•

Address assumptions: consultation does not necessarily mean agreement. Be frank about what is negotiable and what is not.

Teachers working with the youngest students know that, if you use the things that matter to them as content, you can encourage them to learn. Grassroots engagement starts from that same basic premise: speak to people’s passions and they will want to be involved. A lecture on the personal dangers of smoking, accompanied by statistics on the poor health outcomes in a community, is more likely to depress and alienate the audience from a community than encourage them to tackle the problem of tobacco. Understanding the issues that worry the community most—such as access to affordable and healthy food, or closing down the crack houses in a neighborhood—and helping people to find resources to respond to those issues, builds a relationship of reciprocity and mutual respect. This may create opportunities at a later date to help the community collectively mobilize against tobacco use. The simple fact is that community members are likely to make better choices and have more successful programs if you find ways to motivate and inspire involvement.

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 14

There are many guides to assist you in determining how to encourage the involvement of “ordinary people” in your programs. Check the resource guide at the end of this primer for some ideas. A basic plan would include the following steps:

1. Define your aims and goals for involving grassroots community members

2. Identify tools for engaging citizens (see tools for

thought box on page 11, on consultation methods)

3. Identify the groups or individuals that need to be involved (see tools for thought on this page)

4. Develop your plan for recruiting and retaining participants

5. Create a positive and supportive environment for ongoing engagement

6. Identify evaluation criteria and decide on next steps

7. Maintain open lines of communication

Tools for thought: Sociogram

The mental mind map, shown on the right, helps you visualize links and connections you already have or might need to build for grassroots engagement. Your connections can be organizations or individuals. They may be paid service providers or volunteer community activists. They may include people who use your services and who are invested in helping you to improve them. They may include First Nations governments, city planners, researchers, youth, and elders. If you’re a manager, they may be your front line staff or contracted service providers. The more people you can engage from the grassroots, the less resistance you may experience and the more successful your initiative is likely to be. Inclusion, finding ways to engage people, may sometimes look very different from the traditional gathering in a room around a table. Be prepared to be innovative and go to where the people are gathered already and ask permission to visit their space.

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 15

I

Intersectoral collaboration

Intersectoral

people working, with the best of intentions,

within their own particular disciplines and fields . collaboration calls for new work

in breaking down the silos that separate many

Largely through the work of the World Health Organization, it is now widely accepted that the definition of health includes more than not being sick. Health is a resource for everyday life—the ability to realize hopes, satisfy needs, change or cope with life experiences, and participate fully in society. Health has physical, mental, social and spiritual dimensions and, therefore, achieving the vision of improved health in northern

BC requires commitment beyond our systems of public health and health care alone. All individuals, sectors, systems, agencies, political structures and institutions in the community share responsibility for—and reap the rewards of—improved health.

If we accept this premise, then we have to accept that we cannot do this work alone. Embracing the determinants of health and a population health approach requires a new concept: intersectoral collaboration. Increasingly, health care service providers need to look to external, and perhaps unexpected, partners to help promote health and influence public policy, making healthy choices easier for people and more widely supported in the society at large. For example, early childhood educators and schools play a pivotal role in the healthy development of children and can also be a support to help families to live in healthier ways. Faith organizations can play a pivotal role in promoting social justice and can be a point of entry in accessing populations, such as new i m m i g r a n t s , t o encourage proactive e n g a g e m e n t w i t h health services. In fact, once we embrace the determinants of health, we can see many potential partners doing really good work that aligns very well with a population health approach. The challenge is, how do we as health care providers find opportunities to work in new and mutually supportive ways with others, who may or may not have a health care background, but who do share our goals and objectives?

Intersectoral collaboration is, in a nutshell:

“A recognized relationship between part or parts of the health sector with part or parts of another sector which has been formed to take action on an issue to achieve health outcomes …in a way that is more effective, efficient or sustainable than could

be achieved by the health sector acting alone.” WHO

International Conference on Intersectoral Action for Health, 1997.

The tool on the page opposite lays out some simple first steps. If we remember that the first and logical place to start is to focus on respectful and equitable relationships, believing that everyone brings something to the table, the odds of successful intersectoral collaboration improve in our favour.

Dr. Trevor Hancock, a consultant for the BC Ministry of Health, tells the story of the Welsh hospital that sent their carpenter out into the community to retrofit seniors’ homes: “It doesn’t look like health care but the rate of falls requiring seniors to be hospitalized fell dramatically.”

Managing partnerships is important for effective health services delivery. Partners or stakeholders might include the community, civil society organizations, other sectors, district, regional and national authorities, donors, private providers, and others. WHO

(World Health Organization), Managing partnerships.

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 16

Intersectoral collaboration can take many forms—we have identified four in our Healthy Community development work :

Sponsorship—A commitment to provide some material support in return for acknowledgment, verbal and written, in the proceedings.

Cooperation—An agreement to work together to carry out a task, initiative or project, dividing labour and delegating responsibilities.

Collaboration—This is a more formal understanding and usually involves shared power and decision making. It is often short term.

Partnership - This is a full-fledged, long term and ongoing agreement to work together, equitably sharing resources, decisions and work.

I ntersectoral collaboration opportunities. Adapted from Jim Frankish, and Glenn Moulton, “Intersectoral Collaboration on the Non-Medical

Determinants of Health: The Role of Health Regions in Canada”

Tools for thought: Understanding partnership

This tool helps you determine current and potential levels of collaboration.

Approaching and Opening Intersectoral Collaboration Opportunities

Level of partnership Strategies for connecting

Currently no existing partnerships

•

Identify local events or activities and approach, offering concrete support.

•

Initiate conversations about repeating the offer in other venues.

Some informal contacts •

Ask for opportunity to discuss progress of informal work with a view to increasing levels of involvement.

Formal agreements and structures

Jointly developed action plan

• Memorandum of understanding or similar document has been drafted and signed by all parties; usually spells out agreed upon expectations and deliverables.

•

Ongoing team work and joint planning are agreed upon.

•

Meeting agendas created jointly and tasks such as chairing and minute taking are rotated.

Approaching and opening intersectoral collaboration opportunities.

Adapted from Jim Frankish, and Glenn Moulton, “Intersectoral

Collaboration on the Non-Medical Determinants of Health: The Role of

Health Regions in Canada”

Key points:

Setting the Context : Understand the impetus for the partnership

Players : Know who should be involved and how

Process : Identify steps you can take and ways to connect parallel processes and activities.

Value Added : Stress how the partnerships can help ensure sustainability and extend to other mutual interest areas.

Impacting Multiple Planning & Policy Processes : The outcome may be more integrated community capacity to respond (engaging both elected officials and senior administration).

Model Replication : Remember the model can help build cohesion, reduce friction, and look at issues from a “how could we” appreciative perspective.

N

Nurturing healthy public policy

Lasting change lies in our capacity to make sure the community has a memory for what works. Healthy public policy is one way of ensuring that the legacy of good work builds

Canada beyond what Monique Begin called “a nation of pilot projects.”

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 17

The role of policy within any institution, organization or government is to document and ensure adherence to corporate values, philosophies, ideologies and priorities by prescribing how the representatives of that corporate body will behave in practice. It commits the members of that corporate body to allocating resources to make adherence to policy possible, and it calls for attention to be paid to ensuring people have the training, skills, structural support and capacity to uphold a standard. It allows the people who interface with or depend on an organization to predict what to expect and how to effectively engage with its structures.

Policy is the vehicle that enables organizations and governments to “put their money where their mouth is.” If a government claims to value its children, but does not pass legislation and allocate resources to ensure children are safe, well-educated, appropriately fed and given access to early developmental opportunities, if it does not ensure parents a living income and does not plan for affordable housing for families, then it is reasonable to conclude that, in fact, the government does not value its children. If an employer claims to value its workers, but does not implement policy to ensure safe working conditions and provide a healthy workplace, the workers will likely not feel valued and will experience higher rates of illness, stress, accidental injury and lack of engagement. As a result, the employer will deserve a reputation for not valuing its people.

Evidence suggests that the alignment of policies that address the health inequities generated by the determinants of health can result in a multiplication effect; the impact of policies can be increased and the time for such improvements to be visible can be reduced because the determinants of health are so closely connected and build on each other (Evidence

into Action, Saskatoon Health Authority 2008). Therefore, advocating for policy changes that address underlying determinants of health, such as child poverty, becomes an important component of population health and healthy community development work.

Consider, as an example, the achievements that have been made in addressing the negative impacts of tobacco use.

Without legislation and policy, we would still be subjected to second hand smoke in restaurants and on airplanes and advertising would still be promoting tobacco use as a pathway to success. There still is a tobacco use health problem in

Canada, but not to the extent seen in countries that have not created legislation and enforcement to curtail public smoking.

Revisit: Build in a policy Review

Take some time to review your program Policy manual.

Does it reflect the values, philosophical underpinnings and priorities of your program area and team? Do your policies reflect a health inequities lens or pay attention to underlying determinants of health, either for your staff or for the population you serve? Have there been shifts in NH policy or in the legislative landscape that are not reflected in your existing policy manual?

Sustainability of community driven efforts and service providers’ best practices requires a matching level of understanding and action within the institutions and agencies responsible for population health measures. Healthy public policy is the key to ensuring that good ideas and effective practices live on.

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 18

Tools for thought: Identifying policy opportunities

One way of thinking about opportunities for policy development is to think about populations by their place on the life stage continuum. For example, what polices could be developed that would improve the long-term health odds for children in their early years, or that would improve health outcomes for seniors approaching later stages of life? Alternatively, it can be useful to look for transition points on the life course when people, by virtue of being at a critical developmental juncture, are open to learning and making lifestyle changes. Graduation from high school, becoming a new parent, retiring and empty nesting are all good examples of transition points where policy intervention may be particularly well-received and effective.

E

Evidence based decision making

Allocation of resources and decisions about strategies and direction will only ever be as good as the evidence provided for their rationale. As Arthur C.

Clarke wrote in 2001: A Space Odyssey:

“The only hard decision is what to do next.”

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 19

Evidence based decision making is the process of systematically reviewing, appraising and applying the best research findings to ensure optimal decisions. Evidence is defined as any data or information used to identify problems, to assess their magnitude, to explain them and to make decisions, based on the evidence, for their resolution. This

“evidence based” approach was articulated in the 1990s, but the concept dates back to the 1980s, when the focus within health care shifted from trust, conviction and authority to the use of the best available research and practice. (Robust

Decision Making, “Evidence based practice in decision making”)

The assumption underlying evidence based decision making is that assessing the results from a multitude of sources allows decisions to be based on a foundation of research that has been reviewed and considered statistically significant. This review, conducted to specific standards, allows busy practitioners to rely on up to date and relevant research findings, without having to carry out the necessary review work themselves. As a result, better value for the money invested in health care can be expected and better health care means better health outcomes for individuals. There have, however, been some drawbacks. While advances in

“We need to commit to ongoing evaluation and monitoring of interventions undertaken to reduce health inequity. Some can affect change quite quickly. Others will take more time. But we need to have the ongoing measures to show the commitment is still there and the inequities are not going away. And we need more frequent reports than every five years to show those changes.” Dr. Cory

Neudorf, Board of the Canadian Public Health Association and

Medical Health Officer, Saskatoon. Presentation to Responding to

Health Inequities: The Role of Public Health, May, 2009 technology have increased access to a global data bank of research, findings must still be applied within a local context. Further, much of the necessary technological and financial infrastructure needed to ensure evidence banks are relevant and timely to quality improvements are still not in place. The necessary cooperation between government, academic and commercial interests is still lacking. As a consequence, while there is agreement about the need for quality information on which to base decisions, the governance and oversight to put evidence based materials in the hands of policy makers and practitioners is not yet fully developed. In spite of the very real potential contained in systematic, evidence-based approaches to practice and policy,

“(e)vidence alone will never resolve the numerous complex decisions involved in taking care of individuals or making health care decisions for diverse populations.” (Clancy and

Cronin)

Drawbacks aside, evidence based approaches are clearly important. For front line practitioners, clinicians and policy makers, the challenge lies in understanding the rules underlying evidence based material and applying some basic rules of literature review when reading the evidence case.

Cultural competency is also a key trait for developing evidence based decision making. The medical model is not the only source of information for our decision making processes.

“Research findings derived from a single study are rarely definitive, while replication of results in multiple studies offers assurance

Systematic reviews, based on quantitative techniques to evaluate and synthesize a body of incorporate science into clinical decisions, yet to transfer knowledge to the consumer and clinician at the point that the findings are reliable. research in a particular area, represent a core component of there is a recognized need to expedite this process to keep efforts to up with the continuously growing literature and the need of care.” Carol M. Clancy and Kelly Cronin, Health Affairs , 24, no. 1 (2005): 151-162

10.1377/hlthaff.24.1.151 (abstract at:

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 20

We must incorporate respect for other cultural bases of knowledge, such as traditional healing and medicines, in decision making and evidence gathering.

Clearly, objective evidence is an important tool. An evidence based decision making process provides a more rational, credible basis for the decisions we make. A case for our practice decisions must be built on objective evidence that is difficult to refute. Objective evidence can help make the case where competing interests may have undue influence.

Ultimately, a case built on credible, objective evidence strengthens our purpose and effectiveness. Note: some community development approaches, such as Capabilities

Approach “may provide a richer evaluative space enabling improved evaluation of many interventions.” This is an important consideration for evidence based development.

Tools for thought: Literature Review for an Evidence

Based Case—Basic guidelines

A basic literature review should tell you what is known about a topic, what is missing, new or unexplored and what questions need to be considered. You should also emerge with a strong sense of who are the leading researchers in the area and what controversies or consensus have developed. Then, following the cycle below, you can build the evidence case.

Phase Four: Feedback and Evaluation

What are the measures for your program?

What unintended consequences did your decision produce?

Are you satisfied with the results or do you need to change the decision?

P HASE

THE

Steps:

O NE : I DENTIFY

T OPIC

What is it that you want to know about?

What do you already know about the situation?

What local resources exist that can help?

P HASE T HREE :

I MPLEMENTATION

Steps:

Review the evidence.

What are the implications? How does the evidence impact your decision making?

Phase Two: Develop and Evaluate

Sources

Steps:

What credibility do the sources have?

What’s missing? What additional evidence do you need?

How and where can you get that?

Adapted from Voice: The SRC Tool box; Courtesy of the North Carolina Division of

Vocational Rehabilitation Services, George McCoy, Director

W

Weaving it all together

Change is never easy.

Finding the balance between t h e b e s t o f t h e scientific and corporate world of medicine and the emerging fields of organizational change and community development is going to be a challenge. The good news is that there are many practitioners who are seeking this balance as part of their own commitment to personal and professional excellence.

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 21

IMAGINE-action

(IMAGINE in action)

“In health promotion, a settings-based approach is seen as a more effective way to improve people’s health and health behaviour because the emphasis is on changing settings (e.g., workplace, schools) instead of individuals.” (Whitelaw, Baxendale, Bryce, Machardy, Young, & Witney, 2001).

The complexities of applying a population health approach lead some to argue that population health implementation challenges are too large and many to overcome. Change can be difficult and in a fast-paced, ever-shifting health care environment, where skilled human resource shortages are being felt and demand for service is increasing, it may seem like the requirement to shift to a population health approach is just one more impediment to productivity.

The current economic downturn may also lead many to argue that there are no resources and “now is not the time” to invest in upstream approaches to health. However, as Dr.

Marmot, head of the WHO commission on the determinants of health said in 2008, the “…largest gains in life expectancy in the United Kingdom came in the 2 decades of world war.” The reality is that economic crisis can actually kick start the implementation of this emerging approach, which is well-supported by evidence. There is an increased need to access the savings and improved health outcomes that can be realized through prevention and a population based approach to health service delivery, and methodologies supporting this approach are actually costeffective and reasonably easy to implement.

Some health practitioners, particularly those in more acute settings, have trouble seeing how the upstream thinking of population health fits with their work. But it doesn't matter where you deliver your services; there is always somewhere further upstream to look, even in palliative care. In Northern

Health we are fortunate to have a strong foundation to support every practitioner who wishes to apply a population health approach. In fact, by adopting this as one of the four strategic initiatives, Northern Health has given all staff and physicians delivering services in the region a mandate to employ this broader view in planning and providing services. It may feel uncomfortable, at first, given the depth and intensity of our various professional training programs, to devote time and effort to population health. In doing so, however, we achieve better results for a broader range of people than we do by focusing on individual points of professional care alone. We also benefit from the opportunity to work in more collaborative, interdisciplinary ways, and this can enhance the

Health care is a misnomer. Currently, our conception of health care is actually sick care. Population health issues the challenges to shift our thinking so that health care is truly about supporting, enhancing and restoring health. This will free up scare resources so that the services required when people are sick are available to them, reducing wait lists and the social and emotional burdens of disease.

Implementing the Population Health Approach: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/implement/indexeng.phpaspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/implement/index-eng.php

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 22 challenge and reward experienced at work, leading to greater job satisfaction.

Even with the most seemingly intractable issues, it is possible to make a difference. For example, Ireland set a measurable goal to reduce poverty from 15% to 10% within 10 years.

Within 4 years, the rate fell to 5%. The target was achieved and exceeded by the setting of clear goals, coupled with increases in social assistance payments, educational initiatives and employment programs. (Neudorf, Presentation to

Responding to Health Inequities: The Role of Public Health,

May, 2009 )

If you’re not sure where to start, the population health check list (this page) is an excellent jumping off point to help you think about population health and using the IMAGINE tools.

Programs within Northern Health have effectively used this to transform their services, as well as to envision new programs from the ground up. You will also find tools on i-Portal to assist you. And your Population Health Team is only a phone call away (250-649-7061). We hope this primer is useful to you and that you will enjoy the challenge of IMAGINE-action in your work. IMAGINE that: you can apply a population health approach in your planning, programs and practice!

Tools for thought: Population Health Check List

First steps

1. Identify the population of interest: Who is the group you are

working with or want to work with?

2. Describe this population of interest fully including:

Demographics

Health Status

Indicators

Impact of health determinants

Cultural characteristics and issues

3. Identify risks and predictors of disease: What are shared

ailments and issues that matter to this group?

4. Identify points of access: Where can you reach them? Who might be

gatekeepers?

5. Engage the community of interest: Where do they think the

issues lie? Where do they want to start?

Quick tips

• Choose an intervention with a high likelihood of success– involving people in designing the intervention increases the chance of its success

• Develop the intervention—look for the key facilitators in the group

• Implement and evaluate—make sure you are recording what is

working and what is not

• Document the process—Tell your story and share the lessons

Inclusion matters! Remember the old saying, “If you aren't at the table, you're likely on the menu!”

So make sure any efforts include the voices, insights or presence of those we are trying to help.

Resources Consulted

Annenberg Institute, “Engaging Communities” VUE Number 13,

Fall 2006. found at: http://www.annenberginstitute.org/VUE/ fall06/Fruchter.php

Anne-Emanuelle Birn, & Kirby Randolph, PhD, Introduction:

History, public health, and social justice -- the Spirit of 1848 & reproductive health, APHA 15 th

2007

Annual Meeting, Scientific Session,

Bennet, Carolyn. Building a national health care system, CMAJ •

April 27, 2004; 170 (9). http://www.cmaj.ca/cgi/content/ full/170/9/1425?eaf

Butler- Jones, Dr. David. The State of Public Health in Canada

2008. Mohan and Patrick-Mohan “Throw the Money Upstream: An

Alternative Strategy to Improve Public Health.” Nonprofit and

Voluntary Sector Quarterly.2008; 37: 34S-43S

Carolyn M. Clancy and Kelly Cronin, Evidence-Based Decision

Making: Global Evidence, Local Decisions, Health Affairs, the

Policy Journal of the Health Sphere; 24, no. !(2005) 151-162

Coast et al. Editorial “Should the capability approach be applied in Health Economics?” Health Economics Vol 17, Issue 6, may

2008.

Delaney, Faith. Muddling through the middle ground: theoretical concerns in intersectoral collaboration and health promotion

Health Promot. Int. 9: 217-225.

The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public

Health in Canada 2008 Helping Canadians achieve the best health

possible found at: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2008/ cpho-aspc/index-eng.php

Evans, Barer, and Marmor, Why Are Some People Healthy and

Others Not? The Determinants of Health of Populations,

Population Health Program, Canadian Institute for Advanced

Research

Frankish, CJ et al. "Health Impact Assessment as a Tool for

Population Health Promotion and Public Policy." Vancouver:

Institute of Health Promotion Research, University of British

Columbia, 1996.

Hamelin, Christopher. Public Health and Social Justice in the Age

of Chadwick, Cambridge University Press, 1998. A Vision of Social

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 23

Justice as the Foundation of Public Health:

Mohamed Khalil, et al. “Upstream Investments in Health Care:

National and Regional perspectives. ABFM Journal of Family and

Community Medicine, 2005; 12(1)

Nancy Krieger, PhD, “A Vision of Social Justice as the Foundation of Public Commemorating 150 Years of the Spirit 0f 1848,

American Journal of Public Health

Horace Miner, Body Ritual among the Nacirema," American

Anthropologist 58 (1956): 503-507; as PDFat: < http:// www.aaanet.org/pubs/bodyrit.pdf

Dr. Cory Neudorf, Overcoming Health Disparities: What Policy

Analysts Can Do So That Political Leaders Can Act. May 2009

PHABC, Health Inequities in British Columbia: Discussion Paper,

November 2008

Provincial Council of Medical Health Officers, Health Inequities in

British Columbia Discussion Paper.. November 2008. found at: http://www.phabc.org/files/HOC_Inequities_Report.pdf?

NSNST_Flood=0c0578ae53354aa1af6b46607bfb3bbe

Dennis Raphael, ed. Social Determinants of Health: Canadian

Perspectives, 2nd edition, edited by Forewords by Carolyn

Bennett and Roy Romanow. http://tinyurl.com/5l6yh9

Dennis Raphael, Poverty and Policy in Canada: Implications for

H e a l t h a n d Q u a l i t y o f L i f e , f o u n d a t : http://tinyurl.com/2hg2df

Robust Decision Making, “Evidence based practice in decision making” found at: http://www.robustdecisions.com/decisionmaking-technology/evidence-based-practice.php

Dr. David Ullman. Making Robust Decisions: Decision Management

for Technical, Business, and Service Teams, 2006

World Health Organization. Commission on the Social Determinants of Health, Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity through

Action on the Social Determinants of Health, November 2008. found at : http://www.who.int/social_determinants/en/

IMAGINE POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER - 24

Social justice is a matter of life and death. It affects the way people live, their consequent chance of illness, and their risk of premature death. …. Within countries there are dramatic differences in health that are closely linked with degrees of social disadvantage. Differences of this magnitude, within and between countries, simply should never happen. These inequities in health, avoidable health inequalities, arise because of the circumstances in which people grow, live, work, and age, and the systems put in place to deal with illness. The conditions in which people live and die are, in turn, shaped by political, social, and economic forces.

Social and economic policies have a determining impact on whether a child can grow and develop to its full potential and live a flourishing life, or whether its life will be blighted. Increasingly the nature of the health problems rich and poor countries have to solve are converging. The development of a society, rich or poor, can be judged by the quality of its population’s health, how fairly health is distributed across the social spectrum, and the degree of protection provided from disadvantage as a result of illhealth. WHO Commission, WHO, CDSH Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on

Social Determinants of Health. 2008

Your feedback and contributions to this primer are always welcomed. Please send any ideas or suggestions to:

Population Health

Northern Health

Centre for Healthy Living

1788 Diefenbaker Drive

Prince George, BC V2N 4V7

Community Development Frameworks Quick Links

British Columbia Healthy Communities (Integral Capacity Building Framework): http://www.bchealthycommunities.ca/Images/PDFs/Capacity%20Building%20Framework%

20April%202006.pdf

The Scottish Government has an excellent set of resources for community capacity development at: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Education/Life-Long-Learning/

LearningConnections/policytopractice/ccb

A paper on the Capability Approach is found at: http://www.capabilityapproach.com/ pubs/323CAtraining20031209.pdf

UNESCO Capacity Building Framework, 2006: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/ images/0015/001511/151179eo.pdf

POPULATION HEALTH PRIMER… 25

IMAGINE

A CALL TO ENVISION THE FUTURE THROUGH OUR ACTIONS TODAY

We believe the IMAGINE acronym highlights the key activities and directions for improving health outcomes before acute and chronic conditions can take hold and impose their dreadful burdens of reduced quality life, increased pain and disease and premature death. We have found it really helpful as an aide to keeping our eye on the prize and not getting shaken from our path by competing agendas and external threats and pressures.

COMING SOON:

We will be producing sequels to the IMAGINE Primer. First up, a collection of stories from around the Northern Health region that will illustrate and exemplify each of the IMAGINE principles in action. The next publication will be an Evaluation primer that uses the IMAGINE principles to assist in developing measures and methods for more effective capture of the intangibles of successful health promotion and disease prevention work. Further ideas for the Healthy Community Development printing press are most welcome.

Read our other materials:

You can access other reports and documents produced by Northern Health’s Population Health and Healthy Community Development

Program at http://iportal.northernhealth.ca/ClinicalResources/pophealthdata/Pages/default.aspx

10-400-3190 Rev09/09