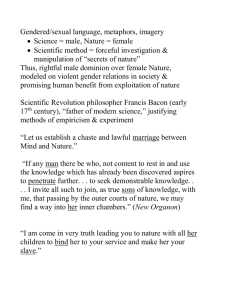

I. INTRODUCTION A. Clever opening B. Facts of Ford v. Lane C

advertisement

OUTLINE: FORD V. LANE by Franklin Goldberg I. INTRODUCTION A. Clever opening B. Facts of Ford v. Lane C. Procedural History D. District Court's Decision and Analysis LEGAL BACKGROUND II. TRADE SECRET LAW A. JUSTIFICATIONS/POLICY BEHIND 1. Provides protection for sensitive information, which in-turn gives incentives to innovate 2. Promotes good-faith transactions in business relations B. HISTORICAL APPROACH TO TRADE SECRET LAW 1. Restatement (First) of Torts §757 C. MODERN STATUTES 1. Unified Trade Secrets Act 2. Michigan Uniform Trade Secrets Act 3. Economic Espionage Act of 1996 a. Broader protections than latter statutes, and stricter penalties b. I am still not sure if I will add this in, but it may round out the discussion III. FIRST AMENDMENT AND PRIOR RESTRAINT A. HISTORY AND POLICY 1. First (and Fourteenth) Amendments 2. Freedom to speak one's mind is essential in discovering truth, enriching intellectual vitality of society, and fulfilling potential of individual B. CASE LAW OFFERS STRONG WEIGHT AGAINST CONSTITUTIONALITY OF PRIOR RESTRAINTS 1. Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931) a. Facts: MN law provided it could restrict, as public nuisance, malicious, scandalous, and defamatory stuff in press. County attorney brought action against "Saturday Press". b. Holding: MN law violates liberty of the press c. Reasoning: freedom of press is essential to nature of free state 2. New York Times v. United States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971) a. Facts: US sought to enjoin NYT from publishing study on Vietnam policy b. Holding: government did not meet its burden necessary for prior restraint c. Reasoning: heavy burden against validity; freedom of press is essential to nature of free state 3. In the matter of Providence Journal Co., 820 F.2d 1342 (1st Cir. 1986) a. Facts: FBI had done surveillance of crime-lord without warrant and in violation of 4th Amendment. FBI destroyed tapes, but kept logs of everything, which Journal requested under FOIA. FBI refused to give over, but after guy 1 died, gave over to Journal. Man's son sought to restrain dissemination. Injunction granted, but Journal published anyway. b. Holding: "A party subject to an order that constitutes a transparently invalid prior restraint on pure speech may challenge the order by violating it." (1342) c. Reasoning: I have a bunch of quotes 4. Several more cases C. IS THERE ANY CASE LAW THAT ALLOWS PRIOR RESTRAINTS? IV. FIRST AMENDMENT (PRIOR RESTRAINT) CONFLICTS WITH TRADE SECRET LAWS A. 1st Amendment encourages free speech and disclosure of information, while trade secret laws restrict people's rights to speak B. How Courts have interpreted Trade Secret Laws 1. Preliminary injunctive relief is common in trade secret cases a. SI Handling Sys. Inc. v. Hesiley, 753 F.2d 1244, 1263-64 (3d Cir. 1985) b. Merck & Co. v. Lyon, 941 F. Supp. 1443, 1455-62 (M.D.N.C. 1996) c. KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, N.V. v. deWit, 415 N.Y.S.2d 190, 191 (Sup.Ct. 1979) 2. But, the trend is that this can only happen when there is a fiduciary relationship between trade secret holder and misappropriator a. Cherne Industrial Inc. v. Grounds & Assoc., Inc., 278 N.W.2d 81 (1981) b. Kewanee Oil Co. v. Bicron Corp., 416 U.S. 470 (1974) c. Ford v. Lane (sic) 3. This interpretation may run afoul of language of trade secret laws a. this section will offer a close reading of the UTSA, Mich. Ann., and perhaps Economic Espionage Act (i.e., I will demonstrate that these statutes, if read strictly, allow injunctive relief if a trade secret is misappropriated.) b. BUT, Trade Secret Statutes are Poorly Written and therefore Leave Room for Varying--and often Contradictory--Interpretations 1) Reiterate Reasoning in Lane 2) Why is it that absent fiduciary relationship, prior restraints are not allowed a) although Lane may be liable under MI statute, 1A provides affirmative defense to Ford's trade secret misappropriation claims. b) Delve into §§ 2-3 of UTSA (1) §2 (a) actual or threatened misappropriation may be enjoined (b) affirmative acts to protect trade secret may be compelled by court order (c) POINT: seems like Lane could have been restrained under this (2) §3 (a) "in addition to or in lieu of injunctive relief," π can get damages (b) If willful and malicious misappropriation exists, court may award exemplary damages (c) POINT: how should a court interpret "in addition to or in lieu of" in light of §2? 2 V. ANALYSIS A. REGARDLESS OF THE REASON (I.E., A POORLY CONSTRUCTED STATUTE OR FLAWED LEGAL REASONING), THE HOLDING IN FORD V. LANE IS IMPROPER. 1. Intro a. Result very much consistent with narrowly tailored precedent as currently interpreted b. Subsequent contentions will offer reasons to veer from this precedent 2. Precedential Reason: analogize to other areas of law a. Favorable Precedent under TRADE SECRET law 1) Protective Orders in TRADE SECRET trials 2) Prior restraints on not only speech, but action, are sometimes permissible in inevitable disclosure cases a) this is inconsistent with general prohibition on prior restraints b) broadens TS laws when courts, as we have seen, seek to limit it c) See PepsiCo., Inc. v. Redmond, 54 F.3d 1262, 1269-72 (7th Cir. 1995) (holding that a former general manager for PepsiCo could not accept a position with Redmond because he would inevitably be forced to use PepsiCo trade secrets for his new employer) d) But, some case law to the contrary (1) See Cambell Soup Co. v. Giles, 47 F.3d 467, 471-72 (1st Cir. 1995) (refusing to grant injunction because employer failed to show that former employee would inevitably disclose trade secrets) (2) FMC Corp. v. Cyprus Foote Mineral Co., 899 F.Supp. 1477 (W.D.N.C. 1995) (holding that inevitable disclosure cannot be a basis for an injunction against employment.) (3) Point: if some courts are willing to restrict actions AND speech, then it makes logical sense to allow for the restraint on ONLY speech b. Favorable Precedent under OTHER areas of law 1) Copyright Cases a) Preliminary injunctions are par for the course (see Lemley and Volokh, Freedom of Speech and Injunctions in Intellectual Property Cases, 48 Duke L.J. 147, 150 (1998) b) Supreme Court has held copyright law to be constitutionally permissible speech restriction 2) Defamation/libel cases: a) General rules (See Vondran v. McLinn, 1995 WL 415153 N.D.Cal. 1995) 1) An injunction that enjoins speech implicates the First Amendment, which generally prohibits any prior restraint on expression. See Organization for a Better Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S.415, 419 (1971); Near v. MN, 283 U.S. 697, 716 (1931). 3 2) Not only are such remedies "extraordinary," they are presumptively invalid. See Nebraska Press Ass'n v. Stuart, 427 U.S. 539, 562 (1976); Keefe, 402 U.S. at 419. 3) Although defamatory speech is not protected by the First Amendment, Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250, 255 (1952), many courts have held that injunctive relief is foreclosed by the availability of an adequate remedy at law. See, e.g., Community for Create Non Violence v. Pierce, 814 F.2d 663, 672 (D.C.Cir. 1987); Alberti v. Cruise, 383 F.2d 268, 272 (4th Cit. 1967); McLaughlin v. New York, 784 F.Supp. 961, 978 (N.D.N.Y. 1992). b) BUT: This is not to say that injunctive relief is never allowed; handful of courts have suggested that defamatory speech can be enjoined, particularly where it injures business-related interests. 1) See, e.g., Lothscheutz v. Carpenter, 898 F.2d. 1200, 1208-09 (6th Cir. 1990) (approving narrow injunction prohibiting defendant from making libelous statements about attorney who represented another party in litigation involving defendant) 2) System Operations v. Scientific Games Dev. Corp., 555 F.2d 1131, 1141-1144 (3rd Cir. 1997) (suggesting that statements by defendant's chairman disparaging plaintiff's products may be enjoined if plaintiff satisfies other requirements for injunctive relief); 3) Martin v. Reynolds Metals Co., 224 F.Supp. 978, 984 (D.Ore. 1963) (defendant required to remove billboard defaming plaintiff's factory); 4) Karamachandani v. Grand Tech, Inc., 678 S.W.2d 580, 582 (Tex.Ct.App. 1984) (upholding injunction barring plaintiff from sending letters urging others to discontinue doing business with defendant). c) An injunction enjoining speech cannot issue, however, unless (1) the nonmoving party is given an opportunity to respond, Carroll v. President and Comm'rs of Princess Anne, 393 U.S. 175, 183 (1968); and (2) the trier of fact has made a finding that the statements sought to be enjoined are libelous or the statements were found to be libelous in a prior proceeding. See, e.g., Lothscheutz, 898 F.2d at 1208-09; Martin, 224 F.Supp. at 982. 3) 'Procedural' cases a) Seattle v. Rheinhart, 467 U.S. 20 (1984) (holding that a protective order restricting the dissemination of confidential information, because issued on good cause, did not violate the 1st Amendment). c. Unfavorable precedent from Constitutional Law is Distinguishable (and shouldn't apply here) 1) prior restraint cases all deal with publications in newspapers or other tangible media (including news broadcasts) a) Near v. Minnesota - "Saturday Press" b) New York Times v. U.S. - "Pentagon Papers" 4 c) CBS v. Davis - "48 Hours" episode d) In the Matter of Providence Journal - Newspaper as well e) Several other cases 2) BUT, Internet≠newspaper (Near, especially, refers to fears during time of Revolution about suppression of speech by English), although precedent does hold that 1st Amendment applies to the internet (see Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S. 844 (1997) 3) SO, here, we are dealing with a man who is posting raw information on the web (this is distinguishable from latter cases) a) there is no commentary along with documents (1) even if Lane wrote a paragraph for each trade secret posted, the court could still come up with a rule that requires the trier of fact to look at the intent of publication (2) i.e., if it is merely to disseminate hurtful information then there can be liability, whereas if it meaningfully adds to public discourse there is not 4) one might argue that Lane's acts were more akin to commercial speech, which receives less protection than non-commercial speech (e.g. print and news media) 3. Practical Reason: Trade secret protections prove illusory if we allow such a big loop-hole. a. reiterate justifications for trade secret law b. explain that there may not be strong justification for requiring fiduciary relationship based on language of statute c. parade of horribles if we allow stuff like this to happen 1) all we need is a 3rd party to feign ignorance as to the origin of documents to allow publication 2) we are then left with potentially judgment-proof defendants (Lane cannot afford Ford's damage award) 3) criminal statutes may be better, but still would allow misappropriators to reek havoc on trade secrets. 4. Policy Reasons - why based on competing policies of trade secret and 1st Amendment law the result in Ford is wrong VI. * POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS* A. WE SHOULD RECLASSIFY TRADE SECRETS: (ADD NOTES ON PROPERTY/PRIVACY) 1. If we classify them as being Property Like, we could rely on the favorable precedent in copyright, procedural, and favorable trade secrets cases listed above a. would allow injunctive relief b. Precedent 1) Ruckelshaus v. Monsato, 467 U.S. 986 (1984) (unanimously holding that trade secrets constitute property and cannot be taken from their owners without just compensation) I am still thinking about these, and may include C.2. in the Analysis section. 5 2) Carpenter v. United States, 484 U.S. 19 (1987) (holding that confidential business information gathered by a Wall Street Journal columnist regarding stock evaluations was the newspaper's property.) 3) See notes on property/privacy 2. Being Business related, it would fall under the favorable precedent in the defamation cases 3. Being commercial Speech, it would be removed from the precedential scope of the unfavorable constitutional cases on prior restraints a. Classify trade secrets as "commercial speech" (or create whole new class of speech for trade secrets) so that the speech can be restrained more than noncommercial speech (i.e., the status quo) 1) Point: Commercial speech is not afforded all the protections of noncommercial speech (Lane and other cases indicate that trade secrets are non-commercial in that they often may not be restrained) 2) Therefore, if we make trade secrets "commercial speech," or judicially classify it outside of its current boundaries, we may be able to restrain it without violating the 1st Amendment VII. CONCLUSION A. FORD V. LANE DECIDED INCORRECTLY, ALTHOUGH CONSISTENT WITH PRECEDENT (AS CURRENTLY INTERPRETTED) B. RAMIFICATIONS OF ADHERING TO THESE DOCTRINE COULD STIFLE INNOVATION OF SPECIFIC BUSINESSES/INDUSTRIES 6