EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

available at www.sciencedirect.com

journal homepage: www.europeanurology.com

Platinum Priority – Prostate Cancer

Editorial by Brian F. Chapin, Sean E. McGuire and Ana Aparicio on pp. 1067–1068 of this issue

Might Men Diagnosed with Metastatic Prostate Cancer

Benefit from Definitive Treatment of the Primary Tumor?

A SEER-Based Study

Stephen H. Culp a,*, Paul F. Schellhammer b, Michael B. Williams b

a

Department of Urology, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA; b Department of Urology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, VA, USA

Article info

Abstract

Article history:

Accepted November 8, 2013

Published online ahead of

print on November 20, 2013

Background: Few data exist regarding the impact on survival of definitive treatment of

the prostate in men diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer (mPCa).

Objective: To evaluate the survival of men diagnosed with mPCa based on definitive

treatment of the prostate.

Design, setting, and participants: Men with documented stage IV (M1a–c) PCa

at diagnosis identified using Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)

(2004–2010) and divided based on definitive treatment of the prostate (radical prostatectomy [RP] or brachytherapy [BT]) or no surgery or radiation therapy (NSR).

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis: Kaplan-Meier methods were used to

calculate overall survival (OS). Multivariable competing risks regression analysis was

used to calculate disease-specific survival (DSS) probability and identify factors associated with cause-specific mortality (CSM).

Results and limitations: A total of 8185 patients were identified: NSR (n = 7811), RP

(n = 245), and BT (n = 129). The 5-yr OS and predicted DSS were each significantly higher

in patients undergoing RP (67.4% and 75.8%, respectively) or BT (52.6 and 61.3%,

respectively) compared with NSR patients (22.5% and 48.7%, respectively)

( p < 0.001). Undergoing RP or BT was each independently associated with decreased

CSM ( p < 0.01). Similar results were noted regardless of the American Joint Committee

on Cancer (AJCC) M stage. Factors associated with increased CSM in patients undergoing

local therapy included AJCC T4 stage, high-grade disease, prostate-specific antigen

20 ng/ml, age 70 yr, and pelvic lymphadenopathy ( p < 0.05). The major limitation

of this study was the lack of variables from SEER known to influence survival of patients

with mPCa, including treatment with systemic therapy.

Conclusions: Definitive treatment of the prostate in men diagnosed with mPCa suggests

a survival benefit in this large population-based study. These results should serve as a

foundation for future prospective trials.

Patient summary: We used a large population-based cancer database to examine

survival in men diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer (mPCa) undergoing definitive

therapy for the prostate. Local therapy (LT) appeared to confer a survival benefit.

Therefore, we conclude that prospective trials are needed to further evaluate the role

of LT in mPCa.

# 2013 European Association of Urology. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Metastatic prostate cancer

Radical prostatectomy

Brachytherapy

Outcomes assessment

* Corresponding author. Box 800422, Charlottesville, VA 22908, USA. Tel. +1 434 243 9325;

Fax: +1 434 982 3652.

E-mail address: shc5e@virginia.edu (S.H. Culp).

0302-2838/$ – see back matter # 2013 European Association of Urology. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2013.11.012

1059

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

1.

prostate—either surgical removal or radiotherapy—on

survival in men diagnosed with mPCa using a large

population-based cancer database.

Introduction

Surgery or radiation therapy are standard treatment

options for men diagnosed with organ-confined prostate

cancer (PCa) and a life expectancy 10 yr [1]. For locally

advanced disease, radiation therapy with androgendeprivation therapy (ADT) is more commonly used.

However, for patients with metastatic disease at the

time of diagnosis, ADT remains the initial management

choice [2]. Despite data demonstrating improved survival

with tumor burden reduction in other malignancies [3–5],

including treatment of the primary tumor itself [6–9],

little data exist for men diagnosed with metastatic PCa

(mPCa). The purpose of this study, therefore, was to

examine the impact of definitive local therapy (LT) of the

2.

Methods

Cases were identified from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End

Results (SEER) database. SEER encompasses population-based cancer

registries covering approximately 28% of the US population and records

basic demographics, tumor site, histology, stage, grade, and treatments

performed. Because the mortality status of most all cases is known,

survival time can be accurately determined [10].

Cases were identified as any man 35 yr diagnosed with malignant

adenocarcinoma (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology,

third edition, code 8140) of the prostate (site code 61.9) between 2004

Table 1 – Patient characteristics

Characteristic

Median age, yr (IQR)^

Race, no. (%)

White

African American

Other

Year of diagnosis, no. (%)

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Marital status, no. (%)^

Single/widowed/divorced

Married

Unknown

PSA, ng/ml, no. (%)^

<10

10–19

20–29

30

Unknown

Tumor grade^

Low to moderate

High

Unknown

AJCC T stage, no. (%)^

T1/T2

T3/T4

Unknown

AJCC N stage, no. (%)^

N0

N1

Unknown

AJCC M stage, no. (%)^

M1a

M1b

M1c

EBRT received, no. (%)

No surgery or radiation therapy

(n = 7811)

72 (63–80)

5670 (72.6)

1570 (20.1)

571 (7.3)

Radical prostatectomy

(n = 245)

62 (58–67)

p valuea

Brachytherapy

(n = 129)

p valueb

p valuec

<0.001

0.514

68 (61–74)

<0.001

0.633

<0.001

0.756

0.004

0.007

0.086

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

0.002

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

0.002

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

186 (75.9)

43 (17.6)

16 (6.5)

91 (70.5)

30 (23.3)

8 (6.2)

0.129

938

957

943

1129

1262

1276

1306

(95.2)

(96.2)

(93.7)

(95.5)

(94.5)

(95.4)

(97.0)

29

23

33

33

51

47

29

(3.0)

(2.3)

(3.3)

(2.8)

(3.8)

(3.5)

(2.2)

15

15

30

20

22

15

12

(1.5)

(1.5)

(3.0)

(1.7)

(1.7)

(1.1)

(0.9)

<0.001

1673 (25.2)

4375 (66.0)

584 (8.8)

26 (11.7)

184 (82.5)

13 (5.8)

632

871

558

4815

935

115

50

17

32

31

19 (16.7)

86 (75.4)

9 (7.9)

<0.001

(8.1)

(11.2)

(7.1)

(61.6)

(12.0)

(46.9)

(20.4)

(6.9)

(13.1)

(12.7)

45

19

11

44

10

(34.9)

(14.7)

(8.5)

(34.1)

(7.8)

<0.001

439 (5.6)

5673 (72.6)

1699 (21.8)

51 (20.8)

187 (76.3)

7 (2.9)

4318 (55.3)

1562 (20.0)

1931 (24.7)

130 (53.1)

113 (46.1)

2 (0.8)

3807 (48.7)

1514 (19.4)

2490 (31.9)

165 (67.4)

68 (27.8)

12 (4.9)

463

5469

1879

0

24

150

71

41

24 (18.6)

94 (72.9)

11 (8.5)

<0.001

91 (70.5)

20 (15.5)

18 (14.0)

<0.001

89 (69.9)

17 (13.2)

23 (17.8)

0.004

(5.9)

(70.0)

(24.1)

(0)

(9.8)

(61.2)

(29.0)

(16.7)

<0.001

16

75

38

54

(12.4)

(58.1)

(29.5)

(41.9)

IQR = interquartile range; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; M1a = nonregional lymph nodes; M1b = bone

metastasis with or without lymph nodes; M1c = distant metastasis with or without bone and/or lymph node involvement; EBRT = external-beam radiation

therapy; NSR = no surgery or radiation therapy; RP = radical prostatectomy; BT = brachytherapy.

^

At the time of diagnosis.

a

Comparing NSR with RP patients.

b

Comparing NSR with BT patients.

c

Comparing NSR with the entire local therapy cohort.

1060

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

[(Fig._1)TD$IG]

and 2010 using all 18 SEER-based registries. Only patients with

documented stage IV (M1a–c) disease at the time of diagnosis based

on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging

Manual, sixth edition, with either radiographic or pathologic confirmation of metastatic disease through the Collaborative Staging System,

were included [11]. Per SEER coding guidelines, age, marital status,

disease grade (low–moderate [Gleason score 7] or high [Gleason 8]),

and clinical AJCC T, N, and M stages were based on data obtained at the

time of diagnosis. Furthermore, the prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

measurement for each patient corresponded to the highest PSA value

recorded prior to diagnostic prostate biopsy and treatment. For each

subject, race was defined as white, African American, or other, and cause

of death (PCa or non-PCa) was based on the SEER cause-of-death

classification.

Cases were grouped based on no surgery or radiation therapy (NSR)

or definitive LT to the prostate (either radical prostatectomy [RP]

[surgery site codes 50 or 70] or brachytherapy [BT] [radiation-specific

codes 2, 3, or 4]). Within the LT group, men were not excluded if they

received adjuvant external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Cases

diagnosed by autopsy or death certificate only or with unknown

radiation therapy, surgery, or metastatic site were excluded. Patients

treated with endoscopic therapy (eg, cryotherapy, transurethral

resection) (n = 1312) or EBRT only (n = 2628) were excluded, since

these treatments did not coincide with the a priori definition of definitive

LT, the latter based on the lack of EBRT organ site–specific codes within

SEER. Incidentally, on initial analyses, survival in these patient groups

was inferior to NSR patients, possibly suggesting that these treatments

were used in a more palliative setting (eg, bone pain, urinary

obstruction).

Outcomes of interest included overall survival (OS) and diseasespecific survival (DSS), as well as factors independently associated with

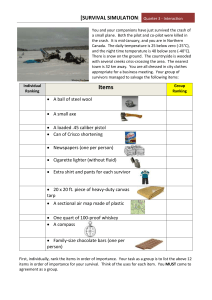

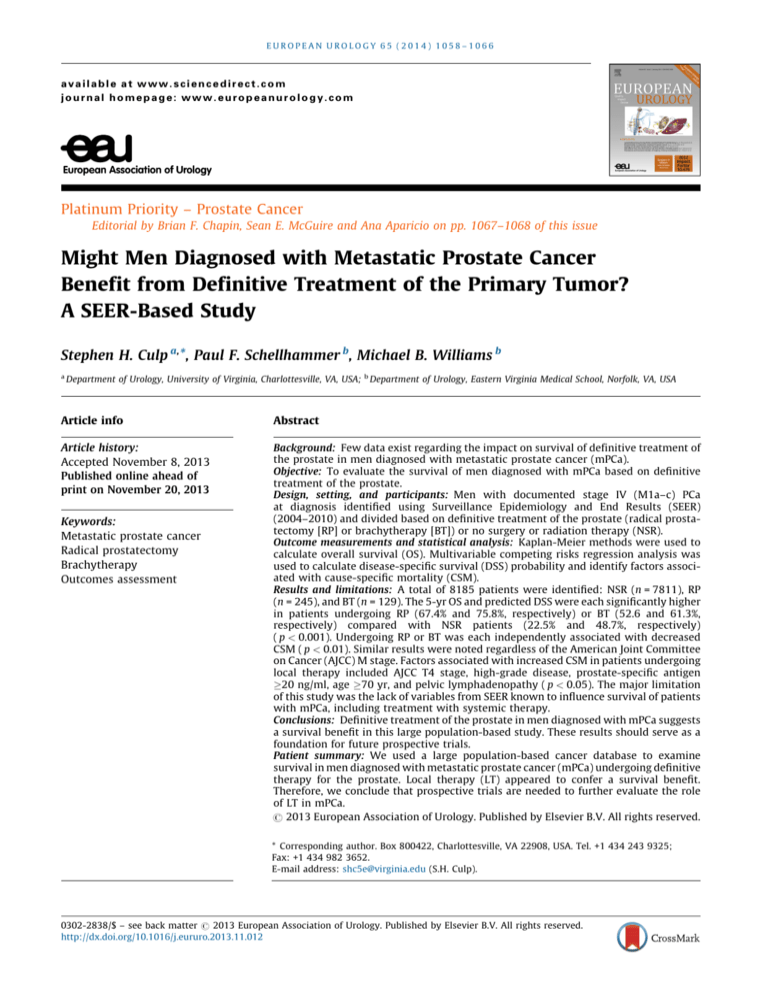

Fig. 1 – (A) Overall survival and (B) cumulative incidence of prostate

cancer (PCa)-specific mortality in patients with metastatic PCa at

diagnosis based on treatment received. For cumulative incidence of

cancer-specific mortality, analyses are adjusted for age at diagnosis;

race; initial prostate-specific antigen; tumor grade; American Joint

Committee on Cancer T, N, and M stages; year of diagnosis; and registry,

and account for the competing risk of non-PCa death. NSR = no surgery

or radiation therapy; RP = radical prostatectomy; BT = brachytherapy.

cause-specific mortality (CSM). Kaplan-Meier methods were used to

determine OS. Even with mPCa, patients can live many years after

diagnosis and may die from non-PCa causes. To account for this situation,

competing risks regression analysis, according to the model of Fine and

Gray [12], was used to calculate the cumulative incidence of PCa-specific

death and DSS probabilities using death from non-PCa as the competing

variable. Stepwise multivariable competing risks regression analysis was

used to identify factors independently associated with CSM using

backward elimination of variables based on the Wald test and a p value

0.20. Variables differing among patient groups were determined using

Pearson chi-square analysis. STATA v.12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX,

USA) was used for all analyses, with a p value 0.05 considered

significant.

3.

Results

A total of 8185 eligible cases were identified, with a median

follow-up of 16 mo (interquartile range [IQR]: 7–31): NSR

(n = 7811), RP (n = 245), and BT (n = 129). Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. A total of 3115 patients

(38.1%) died of PCa: 3048 NSR patients (40.7%), 33 RP

patients (13.5%), and 34 BT patients (26.4%). The 5-yr OS

was significantly higher in patients undergoing either RP

(67.4%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 58.7–74.7) or BT

(52.6%; 95% CI, 39.8–63.9) compared with NSR patients

(22.5%; 95% CI, 21.1–23.9) ( p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). In addition,

undergoing RP or BT was each independently associated

with decreased CSM, with predicted 5-yr DSS probabilities

of 75.8% and 61.3%, respectively, compared with 48.7% for

NSR patients (Fig. 1 and Table 2). In patients dying of nonPCa causes (1284 patients [15.7%]), no significant differences in survival were noted among groups. Although OS

was higher in RP patients compared with BT patients, there

was no significant difference in CSM between the two

groups (Fig. 1).

To account for patients who might benefit least from

LT—either because of progressive disease, significant

comorbidity, or a history of other primary malignancies

that might bias outcomes—analyses were repeated, but this

time excluding patients dying 12 mo from diagnosis

(n = 1813) or with multiple malignant primaries (n = 618).

At a median follow-up of 27 mo (IQR: 18–42), 5-yr OS

continued to be higher in patients undergoing RP (76.5%;

95% CI, 67.0–83.7) or BT (58.2%; 95% CI, 44.5–69.7)

compared with NSR patients (30.6%; 95% CI, 28.9–32.4)

( p < 0.001). Additionally, undergoing RP (subhazard ratio

[SHR]: 0.37; 95% CI, 0.26–0.54; p < 0.001) or BT (SHR: 0.57;

95% CI, 0.37–0.87; p = 0.01) was still each independently

associated with decreased CSM compared with NSR

patients, with 5-yr DSS probabilities of 75.1%, 64.5%, and

46.9%, respectively.

Factors independently associated with increased CSM in

LT patients included age 70 yr, cT4 disease, PSA 20 ng/ml,

high-grade disease, and pelvic lymphadenopathy (Table 3).

Five-year OS (77.3%; 95% CI, 67.4–84.5) and DSS probability

(89.9%) were highest in patients with one or fewer factors

(n = 181 [48.4%]). Although patients with two factors

(n = 116 [31.0%]) exhibited lower 5-yr OS (53.1%; 95% CI,

38.9–65.4) and lower DSS probability (68.7%), survival was

still better than for NSR patients. However, patients with

three or more factors (n = 77 [20.6%]) demonstrated a 5-yr

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

[(Fig._2)TD$IG]

1061

Table 2 – Stepwise multivariable competing risks regression

analysis of patients with metastatic prostate cancer at diagnosis*

Characteristic

Adjusted

SHR

Type of treatment

No surgery or radiation

therapy

Radical prostatectomy

Brachytherapy

High-grade disease^

T4 disease^

(vs <T4 disease)

PSA 20 ng/ml^

(vs PSA <20 ng/ml)

AJCC N stage^

N0

N1

AJCC M stage^

M1a

M1b

M1c

Year of diagnosis

95% confidence

interval

p value

0.38

0.68

1.70

1.25

0.27–0.53

0.49–0.93

1.42–2.04

1.12–1.40

<0.001

0.018

<0.001

<0.001

1.29

1.20–1.40

<0.001

Ref

1.21

1.09–1.33

<0.001

Ref

1.86

2.35

0.93

1.55–2.24

1.94–2.85

0.91–0.95

<0.001

<0.001

<0.001

Ref

SHR = subhazard ratio; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; AJCC = American

Joint Committee on Cancer; Ref = reference; M1a = nonregional lymph

nodes; M1b = bone metastasis with or without lymph nodes; M1c =

distant metastasis with or without bone and lymph node involvement.

*

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results, 2004–2010.

^

At the time of diagnosis.

Table 3 – Stepwise multivariable competing risks regression

analysis of patients with metastatic prostate cancer at diagnosis

undergoing definitive local therapy of the prostate*

Characteristic

Age, yr^

<70

70

AJCC T stage^

T1–T3

T4

Grade of disease^

Low

High

PSA, ng/ml^

<20

20

AJCC N stage^

N0

N1

AJCC M stage^

M1a

M1b

M1c

Adjusted

SHR

95% confidence

interval

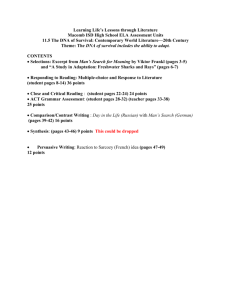

Fig. 2 – Survival of patients with metastatic prostate cancer (PCa) at

diagnosis undergoing local therapy (LT) based on the number of factors

independently associated with an increase in PCa-specific mortality: T4

or high-grade disease, age I70 yr, PSA I20 ng/ml, and pelvic

lymphadenopathy. (A) Kaplan-Meier analysis demonstrating overall

survival; (B) cumulative incidence of PCa-specific mortality, accounting

for the competing risk of non-PCa and adjusted for race, American Joint

Committee on Cancer M stage, year of diagnosis, and registry. Patients

undergoing no surgery or radiation therapy (NSR) are listed as a

reference.

p value

Ref

2.31

1.44–3.72

0.001

Ref

2.09

1.05–4.18

0.037

Ref

3.79

1.30–11.07

0.015

Ref

2.24

1.37–3.66

0.001

Ref

3.13

1.60–6.12

0.001

Ref

3.32

3.66

1.23–9.01

1.23–10.84

0.018

0.019

SHR = subhazard ratio; Ref = reference; AJCC = American Joint Committee

on Cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results, 2004–2010.

^

At the time of diagnosis.

*

OS survival (38.2%; 95% CI, 24.4–51.9) and a DSS probability

(50.1%) similar to NSR patients (Fig. 2).

Subset analyses were performed to determine if survival

differed among groups based on age (<70 vs 70 yr) or

PSA (<20 vs 20 ng/ml), since previous studies have

demonstrated poorer survival in metastatic disease in

older patients (75 yr) [13,14] and in patients with PSA

20 ng/ml [15]. Although both OS and DSS probabilities

were significantly higher in patients <70 yr, only OS was

significantly better in patients 70 yr undergoing LT

compared with NSR patients (Fig. 3 and Table 4). OS and

DSS probability were significantly higher in RP or BT

patients with PSA <20 ng/ml. However, although both RP

and BT demonstrated a significantly higher OS in patients

with PSA 20 ng/ml, only RP patients demonstrated

significantly decreased CSM compared with NSR patients

(Fig. 4 and Table 4).

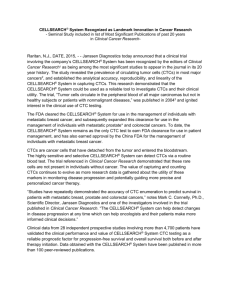

To determine if the extent of metastatic disease affected

survival among groups, subset analyses were performed

based on AJCC M stage (M1a–c) (Fig. 5 and Table 4).

Compared with NSR patients, men undergoing RP exhibited

decreased CSM regardless of M stage and a higher OS in M1b

and M1c disease. In BT patients, OS was higher regardless of

M stage, and CSM was decreased in men with M1c disease.

There were no significant differences in survival among

groups based on individual AJCC M stage in patients dying of

non-PCa causes.

4.

Discussion

PCa is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second

leading cause of death from cancer in American men.

Historically, approximately 25% of men presented with

1062

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

Table 4 – Subset analyses of survival of patients with metastatic prostate cancer at diagnosis based on age, prostate-specific antigen, or

American Joint Committee on Cancer M stage and treatment received*

Age, yr

<70

NSR

RP

BT

70

NSR

RP

BT

PSA, ng/ml

<20

NSR

RP

BT

20

NSR

RP

BT

AJCC M stage*

M1a

NSR

RP

BT

M1b

NSR

RP

BT

M1c

NSR

RP

BT

No. (%)

Adjusted

SHR

95% CI

p value

5-yr

OS, %

95% CI

DSS, yra

p value

1

3

5

3324 (42.6)

202 (82.4)

74 (57.4)

Ref

0.26

0.55

0.17–0.39

0.34–0.88

<0.001

0.014

28.9

71.2

57.4

26.6–31.3

61.6–78.9

22.6–66.6

<0.001

<0.001

86.1

96.7

92.2

57.7

86.9

73.9

45.8

82.0

65.2

5047 (57.6)

46 (17.3)

63 (43.5)

Ref

0.65

0.67

0.37–1.12

0.43–1.03

0.120

0.070

18.1

50.3

48.5

16.5–19.8

30.1–67.5

30.0–64.7

<0.001

<0.001

80.1

86.7

86.2

58.6

70.8

69.9

49.5

63.5

62.5

No. (%)

Adjusted

SHR^

5-yr

OS, %

95% CI

p value

95% CI

p value

DSS, yrb

1

3

5

1503 (21.9)

165 (77.1)

64 (53.8)

Ref

0.26

0.36

0.15–0.45

0.18–0.72

<0.001

0.004

33.7

77.1

71.2

30.4–37.1

66.1–85.0

46.8–85.9

<0.001

<0.001

87.3

96.5

95.3

66.6

89.9

86.5

57.9

86.7

82.3

5373 (78.1)

49 (22.9)

55 (46.2)

Ref

0.58

0.91

0.34–0.97

0.63–1.33

0.039

0.633

19.8

55.7

37.3

18.2–21.5

37.1–70.9

21.4–53.2

<0.001

0.027

81.4

88.8

82.9

55.6

71.3

58.5

44.8

63.0

48.1

No. (%)

Adjusted

SHR^

5-yr

OS, %

95% CI

p value

95% CI

p value

DSS, yrc

1

3

5

463 (5.9)

24 (9.8)

16 (12.4)

Ref

0.24

0.56

0.06–0.95

0.20–1.58

0.043

0.272

35.1

64.3

54.7

28.0–42.3

38.7–81.4

8.6–86.2

0.064

0.014

93.4

98.4

96.3

73.3

92.9

84.1

61.4

89.1

76.2

5469 (70.0)

150 (61.2)

75 (58.1)

Ref

0.35

0.74

0.22–0.55

0.42–1.05

<0.001

0.078

22.9

70.1

55.0

21.2–24.6

58.1–79.2

31.1–64.5

<0.001

<0.001

84.1

94.1

89.2

59.6

83.4

71.0

48.4

77.6

61.9

1879 (24.1)

71 (29.0)

38 (29.5)

Ref

0.33

0.56

0.19–0.57

0.34–0.94

<0.001

0.027

18.6

60.7

53.4

16.1–21.2

42.7–74.6

34.4–69.2

<0.001

<0.001

75.6

91.1

85.4

50.4

80.0

68.3

43.0

75.6

62.1

SHR = subhazard ratio; M1a = nonregional lymph nodes; M1b = bone metastasis with or without lymph nodes; M1c = distant metastasis with or without bone

and lymph node involvement; OS = overall survival; CI = confidence interval; DSS = disease-specific survival; NSR = no surgery or radiation therapy; RP = radical

prostatectomy; BT = brachytherapy; PSA = prostate-specific antigen; AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; Ref = reference.

*

Based on multivariable competing risks regression analysis using death from non–prostate cancer as the competing variable.

a

Adjusted for race; registry; year of diagnosis; PSA; and AJCC T, N, and M stages.

b

Adjusted for age; race; registry; year of diagnosis; and AJCC T, N, and M stages.

c

Adjusted for age, race, registry, year of diagnosis, PSA, and AJCC T and N stages.

either metastatic or lymph node–positive disease. However,

because of PSA screening and associated stage migration,

<5% of men currently present with synchronous metastatic

disease [16]. Although RP and radiation therapy (BT,

conformal radiation therapy, and intensity-modulated

radiation therapy [IMRT]) are routinely used for the

treatment of organ-confined or locally advanced disease,

ADT remains the standard initial management for patients

diagnosed with metastatic disease. Despite the ability of

ADT to prolong survival and curtail disease-related symptoms, resistance to hormone therapy ultimately develops.

The introduction of newer, more novel agents, including

sipuleucel-T [17], abiraterone [18], cabazitaxel [19], and

enzalutamide [20], has shown improvement in survival.

However, 5-yr survival for men with metastatic disease is

only 28%, in stark contrast to nearly 100% for men diagnosed

without mPCa [21].

Decreasing tumor burden, through cytoreductive surgery, radiation, or both, improves survival in a number of

malignancies. In particular, studies demonstrate that

maximal cytoreduction improves survival in patients with

breast cancer [5], colon cancer [3], and ovarian cancer [4], in

addition to increasing tumor response to systemic chemotherapy. Furthermore, treatment of the primary tumor itself

has been associated with improved survival in patients

diagnosed with glioblastoma [8], colon cancer [9], and renal

cell carcinoma [6,7].

Although prospective data do not exist regarding a

survival benefit for patients with mPCa undergoing

treatment of the primary tumor, there are retrospective

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

[(Fig._3)TD$IG]

1063

Fig. 3 – Overall survival (left column) and cumulative incidence of prostate cancer (PCa)-specific mortality (right column) in patients with metastatic PCa

at diagnosis based on age ([A] <70 yr and [B] I70 yr) and treatment received. For cumulative incidence of cancer-specific mortality, analyses are adjusted

for race; prostate-specific antigen; tumor grade; American Joint Committee on Cancer T, N, and M stages; year of diagnosis; and registry, and account for

the competing risk of non–PCa death. NSR = no surgery or radiation therapy; RP = radical prostatectomy; BT = brachytherapy.

[(Fig._4)TD$IG]

Fig. 4 – Overall survival (left column) and cumulative incidence of prostate cancer (PCa)-specific mortality (right column) in patients with metastatic PCa

at diagnosis based on prostate-specific antigen level ([A] <20 ng/ml and [B] I20 ng/ml) and treatment received. For cumulative incidence of cancerspecific mortality, analyses are adjusted for race; age; tumor grade; American Joint Committee on Cancer T, N, and M stages; year of diagnosis; and

registry and account for the competing risk of non-PCa death. NSR = no surgery or radiation therapy; RP = radical prostatectomy; BT = brachytherapy (BT).

1064

[(Fig._5)TD$IG]

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

Fig. 5 – Overall survival (left column) and cumulative incidence of prostate cancer (PCa)–specific mortality (right column) in patients with metastatic PCa

at diagnosis based on American Joint Committee on Cancer M stage [M1a, M1b, or M1c] and treatment received. For cumulative incidence of cancerspecific mortality, analyses are adjusted for age, race, prostate-specific antigen, tumor grade, AJCC T and N stages, year of diagnosis, and registry, and

account for the competing risk of non-PCa death. NSR = no surgery or radiation therapy; RP = radical prostatectomy; BT = brachytherapy.

studies that do indicate improved outcome with prostate

tumor cytoreduction [22–24]. In particular, investigators at

the Mayo Clinic evaluated 79 matched pairs of patients with

pTxN+ PCa undergoing either RP with pelvic lymph node

dissection (PLND) plus orchiectomy within 3 mo of surgery

or PLND with orchiectomy only [23]. They found that

patients undergoing RP with orchiectomy demonstrated

both a higher OS (66% vs 28%; p < 0.001) and a higher DSS

(79% vs 39%; p < 0.001) compared with patients undergoing

orchiectomy alone [23]. In a population-based study using

the Munich Cancer Registry, Engel et al. examined the OS

and relative survival of patients with node-positive disease

undergoing RP (n = 688) in comparison with patients in

whom RP was aborted (n = 250) [24]. Recognizing that there

was a higher number of positive lymph nodes in the aborted

RP group, 10-yr OS (64% vs 28%) and relative survival

(86% vs 40%) were still higher in the RP group. In addition,

on multivariable analysis, not undergoing RP was an

independent predictor of decreased survival (hazard ratio:

2.04; 95% CI, 1.59–2.63; p < 0.0001) [24]. Finally, studies

have shown an increased response to ADT and newer agents

(eg, sipuleucel-T) in patients with metastatic disease who

had undergone prior RP [25–27].

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based

analysis to suggest a possible survival benefit of primary

treatment of the prostate in men diagnosed with mPCa. Our

results demonstrate that patients undergoing definitive

treatment of the prostate (either through RP or BT with or

without adjuvant pelvic radiotherapy) had a higher 5-yr OS

and DSS probability compared with patients not undergoing

LT. It is important to note that in men who died of non-PCa

causes, no survival differences were noted based on

treatment compared with no treatment.

We noted that features independently associated with

increased CSM in patients undergoing LT included age 70

yr, high-grade and high-stage (T4) disease, PSA 20 ng/ml,

and pelvic lymphadenopathy. Consistent with previous

reports demonstrating poorer survival in patients with

metastatic disease who were older or had a higher PSA,

subset analyses in our study demonstrated that patients

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

70 yr and patients with PSA 20 ng/ml were less likely to

benefit from LT [13–15]. In terms of AJCC T and N stages,

although resection of bulky tumor or lymph nodes is

certainly achievable, the potential for leaving disease

behind is greater, which might negate any beneficial effects

of primary tumor cytoreduction. Because of the small

sample size of patients undergoing LT in the current study,

questions regarding benefit with respect to modality

(surgery vs radiation therapy) based on the previously

described factors would be best answered in a prospective

trial.

Mechanisms underlying a survival benefit of cytoreductive treatment remain unknown. Possible explanations in

mPCa include removing tumor-promoting factors and

immunosuppressive cytokines; decreasing the total tumor

burden and thus allowing for an improved response to ADT

and/or chemotherapy; eliminating the primary source of

the dissemination of metastatic cells; and/or eliminating

the primary site, which data have indicated can also be a site

of metastasis through the ‘‘self-seeding’’ hypothesis [28].

Studies have shown that increased circulating tumor cells

are associated with tumor progression and reduced survival

[29]. Removal of the prostate may therefore reduce the

number of circulating tumor cells.

Finally, the most significant findings from this study

were that survival of patients undergoing LT was still

improved regardless of the extent of metastases and that

death from non-PCa causes did not differ among groups

on the whole or based on AJCC M stage. Although the

baseline expectation would be that the greatest benefit

would be seen only in patients with M1a disease, not only

was improved survival noted in patients with either M1b

or M1c disease, but also the difference was most

pronounced in patients with M1c disease. If true, this

finding would be critical for patient enrollment in

prospective clinical trials.

SEER is the only comprehensive population-based

database in the United States that includes disease stage

and grade at the time of diagnosis, initial treatments

performed, and accurate data regarding patient survival. As

such, SEER represents an ideal approach to studying the

survival of patients diagnosed with mPCa in the United

States, especially in recent time periods. We chose to

include only patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2010, as

this time period represented the most up-to-date and

comprehensive collection of validated data regarding PCa

based on the Collaborative Staging System (eg, sites of

metastasis, PSA, surgery-specific coding) and correlated

with the most recent standard of care for patients with

metastatic disease (eg, docetaxel-based chemotherapy and

ADT). In fact, we noted that a more recent year of diagnosis

was associated with decreased CSM in the entire cohort,

likely representing the positive impact of improved agents.

Nonetheless, variables unavailable from SEER undoubtedly

limited our analysis and precluded controlling for any

selection bias that might exist. These variables include

patient performance status, comorbidity, site-specific EBRT

codes, timing and dosage of chemotherapy and/or ADT, and

the use of ADT relative to surgery or BT. The lack of ADT

1065

information is especially important given the influence of

ADT on PCa progression and survival. Finally, SEER lacks

information regarding the extent of bony metastasis, an

entity that undoubtedly influences patient survival.

5.

Conclusions

Despite the inherent limitations of this SEER-based study,

our results suggest that LT for the primary tumor confers a

survival advantage in patients with mPCa at diagnosis.

Because of the lack of site-specific EBRT codes, it was not

possible to examine the effects of IMRT or other forms of

prostate-directed EBRT on patient survival. However, we

would hypothesize that dedicated treatment of the primary

tumor by EBRT would confer similar survival benefits, since

level 1 evidence has shown that ADT plus radiation therapy

compared with ADT alone confers a survival advantage

among patients with high-risk disease and an increased risk

of micrometastases [30]. Although our results are based on

data collected prospectively, our analyses are still retrospective, which limits our ability to fully conclude that

localized treatment of the primary tumor should be part of

the multidisciplinary management of patients with mPCa.

As such, we do not advocate LT based on these data alone

but instead in the context of organized prospective clinical

trials designed not only to demonstrate a survival benefit

with LT of the primary tumor but also to identify patients

most likely to benefit.

Author contributions: Stephen H. Culp had full access to all the data in

the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the

accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Culp, Schellhammer, Williams.

Acquisition of data: Culp.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Culp, Schellhammer, Williams.

Drafting of the manuscript: Culp, Schellhammer, Williams.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Culp,

Schellhammer, Williams.

Statistical analysis: Culp.

Obtaining funding: None.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Culp, Schellhammer,

Williams.

Supervision: Culp, Schellhammer, Williams.

Other (specify): None.

Financial disclosures: Stephen H. Culp certifies that all conflicts of

interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and

affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the

manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties,

or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

References

[1] Scardino P. Update: NCCN prostate cancer clinical practice guidelines. JNCCN 2005;3(Suppl 1):S29–33.

[2] Loblaw DA, Virgo KS, Nam R, et al. Initial hormonal management of

androgen-sensitive metastatic, recurrent, or progressive prostate

cancer: 2006 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology

practice guideline. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1596–605.

1066

EUROPEAN UROLOGY 65 (2014) 1058–1066

[3] Glehen O, Mohamed F, Gilly FN. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from

[17] Small EJ, Schellhammer PF, Higano CS, et al. Placebo-controlled

digestive tract cancer: new management by cytoreductive surgery

phase III trial of immunologic therapy with sipuleucel-T (APC8015)

and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia. Lancet Oncol 2004;5:

in patients with metastatic, asymptomatic hormone refractory

219–28.

prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3089–94.

[4] Bristow RE, Tomacruz RS, Armstrong DK, Trimble EL, Montz FJ.

[18] de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, et al. Abiraterone and increased

Survival effect of maximal cytoreductive surgery for advanced

survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2011;364:

ovarian carcinoma during the platinum era: a meta-analysis. J Clin

Oncol 2002;20:1248–59.

1995–2005.

[19] de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazi-

[5] Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: an overview of the

taxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate

randomised trials. Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative

cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-

Group. Lancet 1998;352:930–42.

label trial. Lancet 2010;376:1147–54.

[6] Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, et al. Nephrectomy fol-

[20] Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzaluta-

lowed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone

mide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2012;

for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1655–9.

[7] Mickisch GH, Garin A, van Poppel H, de Prijck L, Sylvester R. Radical

nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma:

a randomised trial. Lancet 2001;358:966–70.

[8] Nitta T, Sato K. Prognostic implications of the extent of surgical

resection in patients with intracranial malignant gliomas. Cancer

1995;75:2727–31.

367:1187–97.

[21] American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2013. Atlanta,

GA: American Cancer Society; 2013.

[22] Steuber T, Budaus L, Walz J, et al. Radical prostatectomy improves

progression-free and cancer-specific survival in men with lymph

node positive prostate cancer in the prostate-specific antigen era: a

confirmatory study. BJU Int 2011;107:1755–61.

[23] Ghavamian R, Bergstralh EJ, Blute ML, Slezak J, Zincke H. Radical

[9] Temple LK, Hsieh L, Wong WD, Saltz L, Schrag D. Use of surgery

retropubic prostatectomy plus orchiectomy versus orchiectomy

among elderly patients with stage IV colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol

alone for pTxN+ prostate cancer: a matched comparison. J Urol

2004;22:3475–84.

1999;161:1223–7, discussion 1227–8.

[10] Harlan LC, Hankey BF. The surveillance, epidemiology, and end-

[24] Engel J, Bastian PJ, Baur H, et al. Survival benefit of radical prosta-

results program database as a resource for conducting descriptive

tectomy in lymph node-positive patients with prostate cancer. Eur

epidemiologic and clinical studies. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2232–3.

Urol 2010;57:754–61.

[11] Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC cancer staging handbook:

[25] Swanson GP, Riggs M, Earle J. Failure after primary radiation or

TNM classification of malignant tumors. ed. 6. New York, NY: Springer-

surgery for prostate cancer: differences in response to androgen

Verlag; 2002.

[12] Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509.

[13] Humphreys MR, Fernandes KA, Sridhar SS. Impact of age at diagnosis on outcomes in men with castrate-resistant prostate cancer

(CRPC). J Cancer 2013;4:304–14.

[14] Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Mohile S, Golijanin D, Wu G. Prostate

cancer in the elderly: frequency of advanced disease at presentation and disease-specific mortality. Cancer 2012;118:3062–70.

ablation. J Urol 2004;172:525–8.

[26] Thompson IM, Tangen C, Basler J, Crawford ED. Impact of previous

local treatment of prostate cancer on subsequent metastatic disease. J Urol 2002;168:1008–12.

[27] Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:

411–22.

[28] Comen E, Norton L, Massague J. Clinical implications of cancer selfseeding. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011;8:369–77.

[15] Bertaglia V, Tucci M, Fiori C, et al. Effects of serum testosterone

[29] Resel Folkersma L, San Jose Manso L, Galante Romo I, Moreno Sierra

levels after 6 months of androgen deprivation therapy on the

J, Olivier Gomez C. Prognostic significance of circulating tumor cell

outcome of patients with prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer

count in patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate can-

2013;11:325–30.

cer. Urology 2012;80:1328–32.

[16] Ryan CJ, Elkin EP, Small EJ, Duchane J, Carroll P. Reduced incidence

[30] Warde P, Mason M, Ding K, et al. Combined androgen deprivation

of bony metastasis at initial prostate cancer diagnosis: data from

therapy and radiation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer:

PCaSURE. Urol Oncol 2006;24:396–402.

a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;378:2104–11.