Predicting early career research productivity: the case of

advertisement

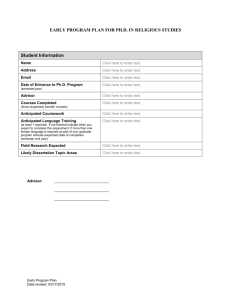

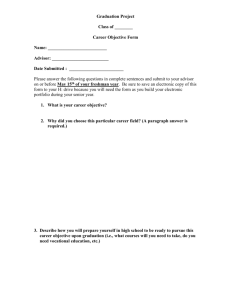

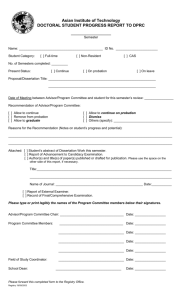

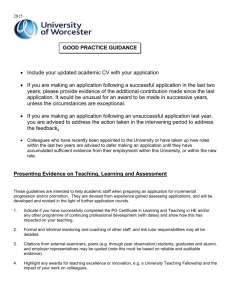

Journal of Organizational Behavior J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/job.178 Predicting early career research productivity: the case of management faculty IAN O. WILLIAMSON1* AND DANIEL M. CABLE2 1 University of Maryland, Robert H. Smith School of Business, College Park, MD 20742-1815, U.S.A. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, The Kenan-Flagler Business School, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3490, U.S.A. 2 Summary We used a longitudinal design to examine the predictors of early career research productivity for 152 management professors over the first six years of their career. Results revealed early career research productivity to be a function of dissertation advisor research productivity, preappointment research productivity, and the research output of a faculty member’s academic origin and academic placement. However, the effects of these predictors varied over time in terms of strength. The findings are discussed in terms of guiding the evaluation and hiring of new researchers in knowledge-based industries. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Introduction There is growing agreement between scholars that the acquisition of high performing human assets can provide firms with sustainable competitive advantages (Coff, 1997). To realize the competitive advantages provided by human assets, organizational decision makers must first identify accurate predictors of employee performance that can be utilized to screen applicants (Wayne, Liden, Kraimer, & Graf, 1999). However, in most cases employers lack full information about job applicants’ abilities, making it difficult to evaluate the probability that an applicant will be a productive employee (Coff, 1997). Nowhere is the problem of talent identification more acute than in settings where the primary concern is knowledge creation, including such industries as biotechnology, information technology, management consulting, and academic universities. In these knowledge-based industries, the ability of employees to create and disseminate high-quality original research reports has direct implications for firms’ competitiveness, reputational capital, and ultimately their survival. For example, biotechnology, information technology and management consulting firms use research reports, commonly referred to as ‘white papers,’ to promote their expertise, attract potential customers, and develop intra-firm knowledge management centers (Hagel & Brown, 2001, Watson, 1998). Indeed, many organizations adopt formal human resource programmes designed to encourage employees to generate * Correspondence to: Ian O. Williamson, University of Maryland, Robert H. Smith School of Business, College Park, MD 207421815, U.S.A. E-mail: iwilliam@rhsmith.umd.edu Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Received 3 December 2001 Revised 15 July 2002 Accepted 27 September 2002 26 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE original research. For example, American Management Systems, Inc (AMS), an international business and information technology consulting firm, uses an associates programme to encourage consultants to publish at least one white paper a year (Watson, 1998). Therefore, hiring employees who are more motivated and able to publish research papers clearly would be valuable to these firms. Unfortunately, the irregular and lagged nature of research innovation makes it difficult to predict which new employees have the greatest probability of making research breakthroughs. The purpose of this paper is to identify predictors that can reduce uncertainty in the selection of researchers. To accomplish this goal, we focused on the research productivity of a specific category of knowledge workers: new business professors in management. We examined this labor segment for several reasons. First, while some academic manuscript outlets differ from commercial white paper outlets, many are quite parallel (e.g., both consultants and management professors publish in Harvard Business Review and Personnel Psychology). Moreover, the analytical and theoretical skills needed to examine research questions in both settings are very similar. Thus, understanding the predictors of faculty research productivity may be informative to firms in other industries that value the creation and dissemination of new research. Second, like many other knowledge-intensive industries, business schools face intense pressures for new hires to quickly become prolific researchers. Intense public scrutiny due to popular press rankings, as well as competition from corporate universities, has increased competition between business schools. A key component of a business school’s competitiveness in this environment is its ability to acquire new faculty members who are capable of creating and disseminating original research (Trieschmann, Dennis, Northcraft, & Niemi, 2000). Of course, many types of academic departments and industries face similar levels of competition and demand for early research contributions, but an advantage of focusing on one type of research is that it ensures comparability in terms of research outlets (i.e., a set journals that publish management research). Finally, a nascent research literature has developed around management research productivity (Long, Bowers, Barnett, & White, 1998; Park & Gordan, 1996), allowing us to integrate and extend past findings. Examining the two prior studies (Long et al., 1998; Park & Gordan, 1996) that have examined the predictors of management faculty research productivity reveals that existing knowledge about research success can be enhanced in three ways. First, both studies have predicted research productivity using few variables in a piecemeal fashion without considering the relative effects of several theoretically relevant variables. For example, Long and colleagues (1998) did not examine individual level factors (e.g., past research performance), while Park and Gordon (1996) did not examine organizational factors (e.g., department quality). As a result, we have limited empirical information to draw upon when deciding how to weight information about researchers during the selection process. Recognizing this limitation, both Long and colleagues (1998) and Park and Gordon (1996) suggest examining a more comprehensive set of variables to delineate the relative importance of research productivity predictors, thus providing more accurate information about research productivity. Second, past research on career success suggests that individuals’ productivity is directly related to the qualifications and abilities of their mentors (Kram, 1985). However, past studies have not examined the relationship between mentor qualifications and early career research productivity. Given the importance of the student-dissertation advisor relationship in the context of academia (Green & Bauer, 1995), an examination of dissertation advisor qualifications should enhance our understanding of the predictors of research productivity. Finally, no research has examined how the predictors of research productivity may evolve over time, highlighting the need for longitudinal research. Although Park and Gordon (1996) reported that strategy faculty research productivity varied widely over the course of their careers, research is needed to examine whether some factors are more predictive immediately after entering an organization while other factors gradually gain predictive validity. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 27 To address these limitations, the present paper builds on the work of Long and colleagues (1998) and Park and Gordon (1996) by simultaneously examining the theory-based predictors of early career research productivity, including dissertation advisor qualifications. By utilizing a longitudinal design, we provide insight into how the predictors of research productivity evolve during the first six years of a career. The results of this study should hold interest for employers who seek to hire individuals capable of producing original research, for doctoral programmes attempting to develop effective researchers, and for job seekers evaluating academic employment opportunities. Theory and Hypotheses Figure 1 provides a graphic overview of the variables and the relationships that comprise our model. Drawing on sociology, psychology, and management theories, we hypothesize that four sets of predictors can be used to predict early career research productivity: (1) advisor qualifications, (2) preappointment productivity, (3) academic placement, and (4) academic origin. In general, Figure 1 suggests that these four sets of predictors can affect a new hire’s research productivity both directly and indirectly. Thus, an individual’s academic advisor is important because he or she imparts research values and knowledge that directly aid the student’s post-appointment research productivity. However, as shown in Figure 1, an advisor also indirectly affects the individual’s early career productivity by helping conduct research projects during graduate school and by helping place the individual into a job, both of which in turn facilitate post-appointment productivity. Likewise, the quality of the university where an individual acquires his or her PhD can lead to greater pre-appointment productivity and job placement, which in turn affect post-appointment productivity. Below we discuss the hypothesized direct effects of these predictors on research productivity, followed by the indirect effects. Figure 1. Hypothesized model of early career research productivity Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 28 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE Direct influences Advisor qualifications Studies of professionals’ careers suggest that an important predictor of early career productivity is the mentoring that individuals receive from their supervisors and advisors (e.g., Scandura, 1992; Scandura & Schrieshem, 1994). Specifically, advisors are thought to enhance the productivity of protégés by providing a variety of career-enhancing functions, such as coaching and assigning challenging work assignments (Kram, 1983). Theoretically, the degree to which an advisor can successfully provide these career-enhancing functions to a protégé is largely dependent on the advisor’s own ability level and accomplishments (Kram, 1985). In the context of academia, the student–dissertation advisor relationship represents a formal mentoring relationship, such that dissertation advisors pass expertise to doctoral students through direct training, providing feedback on manuscript drafts, counselling on research agenda development, or helping protégés select appropriate research outlets for their work (Green & Bauer, 1995). The more skilled and productive a dissertation advisor is, the more likely he or she will imbue students with the research skills and values needed to be productive researchers during the early portions of their careers. As shown in the Figure, this logic leads to Hypothesis 1: Hypothesis 1: The research productivity of individuals’ dissertation advisors is positively related to their post-appointment research productivity. Pre-appointment productivity According to behavioral consistency theory, the best predictor of employees’ future task productivity is their past productivity at that specific task (Wernimont & Campbell, 1968). A person’s previous success at performing a task enhances his or her skill level and self-efficacy in that realm, increasing both the desirability of pursing and the probability of competently repeating that behavior (Mael, 1991). Thus, pre-appointment research productivity (i.e., graduate student publishing record) may be construed as a signal about research ability levels and goals, such that individuals who successfully publish journal articles or have conference papers accepted for presentations during their doctoral programme should continue to be productive at these tasks over the first six years of their faculty career (Park & Gordon, 1996; Rodgers & Maranto, 1989). Thus, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 2: Pre-appointment research productivity will be positively related to post-appointment research productivity. Academic placement Past studies of faculty research productivity have shown that faculty placement, or where individuals obtain a job, may influence their research productivity (Long et al., 1998; Rodgers & Maranto, 1989). One explanation for this finding is that various contextual attributes of an employing school provide faculty members with ‘accumulated advantages’ that make it easier for them to be productive researchers (Long et al., 1998). Thus, when individuals join departments with productive faculty, their personal productivity is likely to increase because an individual’s behavior is influenced by the colleagues that make up his or her social setting (Salancik & Pfeffer, 1978). Specifically, newcomers who obtain positions in departments of active researchers should experience increased research productivity resulting from colleagues who provide expectations, rewards, and ideas that stimulate productivity. Holding departmental productivity constant, new faculty may also derive research advantages by obtaining appointments in departments that have strong public reputations (Pfeffer, Leong, & Strehl, 1977). Public reputation refers to the evaluation of a department’s overall excellence and effectiveness Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 29 by external constituents (Rodgers & Maranto, 1989). Theoretically, journal or conference acceptance decisions may be influenced by a school’s public reputation because editors ascribe positive attributes to individuals’ manuscripts based on their organizational affiliation (Pfeffer et al., 1977). For example, the public reputation of a faculty member’s department might influence editors’ choices of reviewers, interpretations of reviewer comments, and judgments about manuscript acceptance. Thus we hypothesize: Hypothesis 3: The departmental scholarly output of individuals’ academic placements will have a positive relationship with post-appointment research productivity. Hypothesis 4: The public reputation of individuals’ academic placements will have a positive relationship with post-appointment research productivity. Indirect influences Advisor qualifications As shown in Figure 1, in addition to directly influencing faculty research productivity, advisors may also indirectly affect faculty productivity by influencing the pre-appointment research productivity of their protégés. To the extent that advisors enhance technical skills and inculcate research values in their protégés, it is logical that the protégés of prolific dissertation advisors will be productive while under their direct tutelage (Kram, 1985). Therefore, we hypothesize: Hypothesis 5: The research productivity of individuals’ dissertation advisors will be positively related to pre-appointment research productivity. We also expect dissertation advisor productivity to indirectly affect faculty productivity by influencing the quality of protégés’ academic placements. An important element of supervisor mentoring is the sponsoring of protégés for desirable jobs (Kram, 1985). Since dissertation advisors write letters of recommendation and contact universities concerning employment opportunities on behalf of their students, having a prolific advisor can influence the placement of a doctoral student (Cable & Murray, 1999). Therefore, we predict: Hypothesis 6: The research productivity of individuals’ dissertation advisors will be positively related to the quality of their academic placements, both in terms of (a) departmental scholarly output and (b) public reputation. Pre-appointment productivity We also expect pre-appointment productivity to indirectly affect post-appointment productivity by influencing the type of jobs that individuals receive. According to Merton’s (1973, p. 293) examination of universalism, institutions of science work best when ‘recognition and esteem accrue . . . to those who have made original contributions to the body of scientific knowledge.’ Because the most direct measure of a researcher’s contribution to scientific knowledge is their research productivity, we expect that faculty who develop strong research records during graduate school will be more likely to receive job opportunities at prolific research departments with positive public reputations (Cable & Murray, 1999). Hypothesis 7: Individuals’ pre-appointment research productivity will be positively related to the quality of their academic placements, both in terms of (a) departmental scholarly output and (b) public reputation. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 30 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE Academic origin The graduate programme that an individual attended may also provide accumulated advantages that indirectly enhance research productivity. First, graduate programmes with high departmental scholarly output and public reputations may provide research advantages that increase the pre-appointment publication and presentation success of their students, which in turn will impact post-appointment research productivity. Compared with individuals from departments with low levels of scholarly output, individuals from graduate programmes with high levels of scholarly output may be more likely to receive advanced research training and have a greater opportunity to join fruitful research projects by virtue of being around scholars who are actively engaged in research (Long et al., 1998). This, in turn, may increase individuals’ pre-appointment publications and presentations. In addition, individuals from graduate programmes with high public reputations, as opposed to low public reputations, may have a greater opportunity to meet and develop relationships with influential members of the professions (e.g., frequently published researchers and editors) via research presentations and conferences hosted by their school (Long et al., 1998). As a result, doctoral students at high public reputation schools are likely to gain knowledge of and develop ties to the various gatekeepers of the profession, which may influence the acceptance rates of their initial publication and presentation submissions. Therefore, we predict that: Hypothesis 8: The departmental scholarly output of an individual’s graduate programme will be positively related to (a) pre-appointment publications and (b) pre-appointment presentations. Hypothesis 9: The public reputation of an individual’s graduate programme will be positively related to (a) pre-appointment publications and (b) pre-appointment presentations. Second, we propose that individuals’ graduate programmes, both in terms of departmental scholarly output and public reputation, will affect their academic placement and will therefore have an indirect affect on their post-appointment research productivity. As noted by Long, Allison, and McGinnis (1979: p. 816), ‘One of the most persistent findings in the study of stratification in science is the substantial correlation between the prestige of the university department which currently employs a scientist and the prestige of his (or her) doctoral department.’ One explanation for this finding is that universities rely on the departmental productivity or public reputation of an individual’s graduate programme as a signal of his or her research ability (Long et al., 1979). Hypothesis 10: The departmental scholarly output of individuals’ graduate programmes is positively related to individuals’ academic placements in terms of (a) departmental scholarly output and (b) public reputation. Hypothesis 11: The public reputation of individuals’ graduate programmes is positively related to individuals’ academic placements in terms of (a) departmental scholarly output and (b) public reputation. Gender differences The research productivity literature indicates consistent differences between male and female faculty, such that men tend to produce greater quantities of publications then women (e.g., Over, 1982; Zuckerman & Cole, 1975). Various factors have been offered to explain this finding, such as sex discrimination in the allocation of resources, career interruptions, and mentorship (Park & Gordon, 1996; Rodgers & Maranto, 1989). To control for possible gender effects in our model, we examined the effect of protégé gender on post-appointment research productivity. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 31 Organizational Context The data used for this study consisted of information on 152 management faculty accepting their first academic jobs upon completion of their PhD programme from 1987–1995. During this period of time the job market for management doctoral students was fairly strong, thus qualified graduates typically had options in terms of picking their academic affiliation. Data were limited to faculty accepting positions at domestic universities with AACSB accredited doctoral programmes in management. During the time frame of the study 95 schools fit this description. Data collection was limited to individuals hired by one of these 95 schools to account for research productivity differences between non-PhD programme and PhD programme institutions during this time frame (see Park & Gordon, 1996 for more information). In total, faculty in our sample were employed by 67 different colleges and universities in 35 different states. Method The target sample for our study consisted of management faculty in their first jobs after finishing graduate school. Specifically, we studied faculty who in 1995 were working at management departments in domestic American Assembly of Collegiate School of Business (AACSB) accredited business schools, and who started their jobs during the period of 1987–1992. Past research has found that faculty hired by institutions with doctoral programmes in management have significant higher levels of research productivity than faculty hired by institutions without management doctoral programmes (Park & Gordon, 1996). Thus, to control for doctoral programme effects, in our study we limited our sample to those departments with doctoral programmes in management. According to the AACSB Guide to Doctoral Programs in Business and Management (Soete, 1995), a total of 95 American business schools offered doctoral degrees in management in 1995. The McGrawHill Directory of Management Faculty 1995–1996 (Hasselback, 1996) was used to ascertain which individuals at each of the 95 schools fit the specifications of the target sample. The McGraw-Hill Directory, while not exhaustive, is one of the best available lists of US management faculty and has been used in past research to identify management faculty (e.g., Park & Gordon, 1996). The directory identified 211 first-time assistant faculty members who accepted jobs between 1987 and 1992. However, missing or unavailable data across all variables (e.g., advisor, graduate programme) resulted in a working sample size of 152, 72 per cent of the faculty members with job start years between 1987 and 1992. For faculty members that were not included in our study we collected data on their journal publication productivity during the first six years of their career. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) results revealed that nonsampled faculty members did not differ significantly from sampled faculty members in terms of the number of early career journal publications ( p > 0.18), suggesting that our sample was representative of the target sample. The 152 faculty in our sample represented several areas of the management discipline, with 31 per cent identifying organizational behavior/organizational theory as their primary research area, 25 per cent identifying themselves as strategy researchers, 15 per cent working in the area of quantitative methods/management science, 10 per cent identifying themselves as human resource management researchers, and the remaining 19 per cent conducting management research across the areas of ethics, entrepreneurship, international management, and management information systems. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 32 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE Measures Research productivity Two measures of research productivity were used: (1) number of academic journal publications, and (2) number of national Academy of Management (AOM) conference presentations. Following the procedures used by Park and Gordon (1996) and Long and colleagues (1998), the number of academic journal publications for each faculty member was obtained by recording the total number of facultyauthored publications appearing in the premier management journals from 1983 to 1998. Consistent with Cable and Murray (1999) our list of premier management publications consisted of the top 21 management journals identified by Gomez-Mejia and Balkin (1992). The Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) and ABI/Inform (ProQuest Direct) databases were used to obtain the publication counts for each faculty member by year. Only articles and research notes were counted as publications. Comments, book reviews, and editorials were not included. Each faculty publication was weighted for quality using the journal quality ratings provided by Gomez-Mejia and Balkin (1992). Gomez-Mejia and Balkin (1992) reported that their ratings were strongly correlated to the 1990 Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) impact factor (r ¼ 0.78) and Extejt and Smith’s (1990) subjective journal rankings (r ¼ 0.86), suggesting that their ratings are valid measures of journal quality. The weights assigned to each journal article along with the 1990 SSCI impact factors for each journal are provided in Table 1. Table 1 also includes the 2001 SSCI impact factors for each journal, which are strongly correlated (r ¼ 0.88) with the 1990 SSCI impact factors. This suggests that the relative impact of the selected management journals has not change much in the last decade. Table 1. Set of management journals and publications Journal name Journal quality ratinga Academy of Management Journal Strategic Management Journal Journal of Management Journal of Applied Psychology Academy of Management Review Management Science Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes Journal of International Business Studies Administrative Science Quarterly Personnel Psychology Journal of Organizational Behavior Industrial and Labor Relations Review Human Relations Decision Science Journal of Management Studies Journal of Applied Behavioral Science Industrial Relations Harvard Business Review Journal of Vocational Behavior Psychological Bulletin Journal of Occupational Psychology 1990 SSCI 2001 SSCI impact factor impact factor Number of publications in journal by faculty in sample 4.52 4.06 3.60 4.45 3.83 3.37 4.14 1.56 1.79 0.43 1.78 1.54 1.00 1.31 2.83 2.68 1.31 1.98 3.16 1.50 1.27 47 39 28 25 21 14 13 3.26 4.60 3.81 2.85 3.79 3.36 3.50 3.43 3.45 3.62 3.19 3.21 2.85 3.48 0.43 2.85 1.03 0.58 2.06 0.50 0.61 0.98 0.40 1.44 1.24 1.19 3.72 0.96 0.87 3.98 2.11 1.16 1.65 0.86 0.72 0.63 13 11 10 10 7 8 6 5 5 3 2 2 1 1 1.11 2.47 1.70 6.81 0.86 Total ¼ 271 a Ratings taken from Gomez-Mejia and Balkin (1992). Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 33 The annual national AOM meeting is the premier academic conference within the management discipline. While not as prestigious as journal publications, AOM conference presentations represent a viable means of disseminating original research and have been shown to affect the academic placement of management doctoral students (Cable & Murray, 1999). Presentation counts were obtained by counting the number of faculty-authored papers presented at the national AOM conference from 1983–1998. For both journal publications and conference presentations, we were interested in faculty performance (a) prior to starting their first job and (b) after they started their first job. Pre-appointment publication productivity and pre-appointment presentation productivity were measured as the journal publications and conference presentations by a faculty member prior to and including the year they began working their first job. The job start year of each faculty member was obtained from the McGraw-Hill Management Directory (Hasselback, 1996) or from schools’ web page documentation. Post-appointment publication productivity and post-appointment presentation productivity were measured by counting the number of journal publications and conference presentations by a faculty member in the six years after the year they accepted their first academic job. We created measures of both the first three years (years 1–3) and the second three years (years 4–6) of a faculty member’s research productivity to examine the effect of the predictors over the course of a faculty member’s career. The three- and six-year marks were adopted because most new faculty members face a critical three-year review when their research trajectory is evaluated and a six-year tenure review when their research productivity is an important factor in their tenure decisions. Due to skewness in the distributions of the pre- and post-appointment publication counts and pre- and post-appointment presentation counts, a natural log transformation was performed on these measures for model testing. Dissertation advisor research productivity The Dissertation Abstracts Online (DAO) database was used to obtain the name of each faculty member’s dissertation advisor. The SSCI and ABI/Inform (ProQuest Direct) were then used to obtain counts of the total number of advisor-authored publications that appeared in the top 21 management journals (as identified by Gomez-Mejia & Balkin, 1992) during the 10 years prior to the year an advisor’s protégé started their job. Similar to the faculty publication variable, each of the advisors’ journal publication was weighted for quality using the journal quality ratings provided by Gomez-Mejia and Balkin (1992). If a faculty had two advisors we computed the average of the publication counts for both advisors. In those cases where a dissertation advisor co-authored a publication with a faculty member, the publication was included in the dissertation advisor’s productivity count if they had the higher authorship position (i.e. first author), otherwise the publication was included in our measure of faculty research productivity. Skewness in the distribution of advisor publication counts necessitated the use of a natural log transformation for model testing. Academic placement Two attributes of faculty’s academic placement were measured: departmental scholarly output and department public reputation. Our measure of departmental scholarly output consisted of the average cumulative number of journal articles published by a management department’s faculty over the 1987– 1995 period. Using the McGraw Directory of Management Faculty (Hasselback, 1996), the names of each assistant, associate, and full professor who was employed in the management department of each graduate school in 1995 was obtained. The SSCI and ABI/Inform Global were then used to gather information about the cumulative number of publications each department’s faculty member had in the 21 journals identified by Gomez-Mejia and Balkin (1992) during the period of 1987–1995. Consistent with past research (Howard, Cole, & Maxwell, 1987), the average number of departmental faculty publications was determined by summing the total number of faculty publications and dividing by the total number of faculty in a department. To avoid confounding the variable we did not include Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 34 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE the focal faculty member’s publication productivity (including any articles co-authored with department faculty) when compiling his or her department’s total faculty publications, nor was the faculty member included in the total faculty count. The Gourman Report (Gourman, 1996) rating was used to measure the public reputation of a faculty member’s academic placement. The Gourman Report has been used to measure academic programme reputation in past research (Cable & Murray, 1999; Gomez-Mejia & Balkin, 1992), and is presumably the only numerical rating of virtually every graduate programme in the United States. Each school receives a continuous overall rating from 1.0 to 5.0. Whenever possible, we used the Gourman Report ratings for the degree granting institution’s business doctoral programme; if the business doctoral programme rating was not provided we used the Gourman rating of the overall graduate school. Although Gourman ratings have been validated in past research (Cable & Murray, 1999), we provided additional validation by examining the relationship between Gourman Report ratings, the three-year mean GMAT scores of a school’s business PhD students (Soete, 1995), and the management department rankings developed by Long and colleagues (1998) for each of the 95 AACSB accredited business schools with doctoral programmes in management. The correlations between the Gourman Report ratings and these two indexes were 0.63 ( p < 0.001) and 0.70 ( p < 0.001) respectively, suggesting that the Gourman Report is a reasonable indicator of a department’s public reputation. Academic origin Similar to academic placement, we measured both the scholarly output and the public reputation of a faculty member’s academic origin (i.e., their graduate school). The identical methodology described above to measure scholarly output of academic placement was also employed to measure the departmental scholarly output of a faculty member’s academic origin, and the 1996 Gourman Report (Gourman, 1996) was used to measure the public reputation of a university’s management department. Results The 152 faculty members comprising the sample published 285 papers in the premier management journal set during the first six years of their academic job, for an average of 0.31 articles per year. Several faculty coauthored papers with other members of the sample, thus only 271 distinct papers were produced overall. Table 1 presents the number of articles published in each of the 21 journals comprising the set of premier management journals. To test the proposed relationships we estimated a covariance structural equations model using LISREL 8.3 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1999). The hypothesized model depicted in Figure 1 consisted of nine latent endogenous variables and three latent exogenous variables each with one indicator assumed to contain no measurement error. The means, standard deviations, and correlations among all variables appear in Table 2. We assessed the overall fit of the model to the data with chi-square, the goodness-offit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI), the comparative fit index (CFI), the incremental fit index (IFI), the parsimony ratio (PRATIO), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Chi-square statistics that are not statistically significant suggest that a model adequately fits the data, while GFI, AGFI, CFI, and IFI scores at or above 0.90 are believed to indicate acceptable fit (Medsker, Williams, & Holahan, 19941). For the RMSEA index, values below 0.08 1 Medsker and colleagues (1994) recommend evaluating a hypothesized model relative to plausible alternative models. We tested three alternative models which did not significantly improve upon the hypothesized model. Due to space constraints only the results of the hypothesized model are presented. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) Mean Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2 3 4 (0.46) 0.09 (19.62) 0.02 0.09 (1.10) 0.05 0.01 0.27 (0.64) 0.02 0.19 0.09 0.03 0.01 0.37 0.25 0.05 0.10 0.07 0.10 0.52 0.01 0.03 0.09 0.24 0.09 0.20 0.03 0.05 0.03 0.26 0.07 0.15 0.03 0.25 0.00 0.02 0.05 0.27 0.11 0.10 1 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 (2.52) 0.24 (1.32) 0.03 0.08 (0.83) 0.23 0.16 0.48 (1.02) 0.37 0.35 0.06 0.26 (3.69) 0.32 0.39 0.17 0.34 0.18 (1.51) 0.21 0.28 0.08 0.23 0.25 0.43 (5.88) 0.19 0.40 0.07 0.29 0.23 0.53 0.50 (1.80) 5 Note: n ¼ 152. The numbers in parentheses on the diagonal are standard deviations. Correlations greater than 0.16 are significant at that 0.05 level. a Means and standard deviations calculated using untransformed data; natural log was used to determine correlations. 1. Gender (1 ¼ male) 0.69 2. Dissertation advisor productivitya 16.37 3. Academic origin departmental scholarly output 2.40 4. Academic origin public reputation (1–5) 4.46 5. Pre-appointment publicationsa 1.12 6. Pre-appointment presentationsa 0.99 7. Academic placement public reputation (1–5) 4.03 8. Academic placement departmental scholarly output 1.71 9. Post-appointment publications (years 1–3)a 2.30 10. Post-appointment presentations (years 1–3)a 1.33 11. Post-appointment publications (years 4–6)a 4.63 12. Post-appointment presentations (years 4–6)a 1.66 Variable Table 2. Means, standard deviations and correlations between variables EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 35 J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 36 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE are considered indicative of good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). A definitive cut-off point does not exist for the PRATIO, however, the higher the score the greater the parsimony of the model (Mulaik, James, VanAlstive, Bennett, Lind, & Stilwell, 1989). The chi-square for the hypothesized model was significant (2 ¼ [17, n ¼ 152] ¼ 35.35, p < 0.001), the AGFI was 0.84, and the PRATIO was 0.26; however, the GFI was 0.97, the CFI was 0.96, the IFI was 0.96, and the RMSEA was 0.07 (90 per cent confidence interval ¼ 0.04 to 0.12). All four of the latter values suggest that the hypothesized model adequately fit the data. In addition, the chi-square difference test between the chi-square of the hypothesized model and the null model was significant (2 ¼ 46, n ¼ 152) ¼ 354.80, p < 0.001), suggesting that the hypothesized model provided a significantly better fit to the data than the null model. Table 3 contains the maximum-likelihood parameter estimates, significance levels, and R2s for the hypothesized model. First, we will present the results for the hypothesized direct relationships. Hypothesis 1 predicted that dissertation advisor research productivity would be positively related to both faculty post-appointment publication and presentation productivity. However, advisor research productivity did not share a significant direct relationship with either faculty post-appointment publication or presentation productivity during years 1–3 or 4–6. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was not supported. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, faculty pre-appointment presentations significantly predicted postappointment presentations in years 1–3 and 4–6 ( ¼ 0.27 and ¼ 0.17, respectively). Preappointment publication productivity shared a significant direct effect on post-appointment publication productivity in years 1–3 ( ¼ 0.27) but not years 4–6, providing partial support for Hypothesis 2. In addition, pre-appointment publication productivity also significantly predicted post-appointment presentations in years 1–3 ( ¼ 0.18) and pre-appointment presentations significantly predicted post-appointment publications in years 1–3 ( ¼ 0.23). The departmental scholarly output of a faculty member’s academic placement had a significant direct effect on post-appointment presentation productivity in years 1–3 ( ¼ 0.20). However, department scholarly output did not significantly predict post-appointment publication productivity in years 1–3, nor did it predict post-appointment publication or presentation productivity in years 4–6. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported. The public reputation of faculty’s academic placement did not share a significant relationship with post-appointment presentations or publications. Thus, Hypothesis 4 was not supported. Next, we present the results of the hypothesized indirect relationships. Hypothesis 5, which predicted that dissertation advisor research productivity would be positively related to faculty preappointment publications and presentations, was supported ( ¼ 0.19 and ¼ 0.35, respectfully). Advisor research productivity, however, was not significantly related to either the departmental scholarly output or the public reputation of faculty’s academic placement. Therefore, Hypotheses 6a and b were not supported. Pre-appointment publications were significantly related to the departmental scholarly output of an individual’s academic placement ( ¼ 0.20), but pre-appointment presentations did not predict departmental scholarly output. Thus, Hypothesis 7a was partially supported. Pre-appointment publications and presentations did not significantly predict the public reputation of an individual’s academic placement; therefore, Hypothesis 7b was not supported. Hypotheses 8a and b predicted that departmental scholarly output of an individual’s graduate programme would be positively related to pre-appointment (a) publications and (b) presentations. Hypothesis 8a was not supported; however, graduate program scholarly output was significantly related to preappointment presentations ( ¼ 0.25), providing support for Hypothesis 8b. The public reputation of an individual’s graduate programme was not significantly related to pre-appointment publications or presentations. Thus, Hypotheses 9a and 9b were not supported. Hypotheses 10a and b, that the departmental scholarly output of an individual’s graduate programme would share a positive relationship with the (a) departmental scholarly output and (b) public reputation of an individual’s academic placement, were not supported. On the other hand, the public reputation of an individual’s graduate programme was significantly related to the departmental scholarly output and Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2 3 *p < 0.05. Outcomes 1. Pre-appointment publications 2. Pre-appointment presentations 3. Academic placement public reputation 0.05 0.09 4. Academic placement departmental 0.20* 0.15 scholarly output 5. Post-appointment publications (years 1–3) 0.27* 0.23* 0.01 6. Post-appointment presentations (years 1–3) 0.18* 0.27* 0.11 7. Post-appointment publications (years 4–6) 0.01 0.06 0.01 8. Post-appointment presentations (years 4–6) 0.05 0.17* 0.05 9. Academic origin public reputation R2 0.04 0.20 0.43 1 0.27 0.22 0.12 6 0.33* 0.40* 5 0.16 0.20* 0.09 0.12 0.14 0.06 0.41* 4 Endogenous variables Beta matrix () 0.23 7 0.01 0.12 0.43* 0.25* 9 0.35 0.08 8 Antecedents Table 3. Maximum-likelihood parameter estimates for the hypothesized model of research productivity 0.01 0.06 0.02 0.03 Gender 0.07 0.13 0.12 0.09 0.19* 0.35* 0.04 0.06 Dissertation advisor productivity 0.27* 0.07 0.25* 0.02 0.03 Academic origin scholarly output Exogenous variables Gamma matrix () EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 37 J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 38 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE Figure 2. Significant path coefficients of hypothesized model public reputation of an individual’s academic placement ( ¼ 0.25 and ¼ 0.43, respectively). Therefore, Hypotheses 11a and b were supported. Finally, in terms of an individual’s gender, there was no significant relationship between gender and post-appointment publications or conference presentations over years 1–3 or 4–6. In summary, results suggest that advisor qualifications, pre-appointment productivity, academic placement, and academic origin all directly and/or indirectly influence faculty early career research productivity. Figure 2 provides a clear overview of the findings by depicting all of the statistically significant path coefficients of the hypothesized model. Because the ultimate outcome of interest in this study is post-appointment productivity, it is informative to examine the total (i.e., direct þ indirect) effects of each predictor on publications and presentations. Accordingly, Table 4 shows the standardized total effects of each predictor provided by LISREL. It is interesting to note that the total effects of the predictors vary over the course of an individual’s early career. For example, pre-appointment publications and presentations had the largest total effects on post appointment publications in years 1–3; however, advisor research productivity had the largest total effect on publication productivity in years 4–6. Similarly, pre-appointment publications had large significant total effects on post-appointment publication and conference presentation productive in years 1–3, but insignificant total effects in years 4–6. Given that a unique contribution of our study is examining the system of relationships regarding new faculty productivity, it is interesting to examine the total effects of the predictors on academic placement, both in terms of public reputation and departmental scholarly output. Thus, Table 5 presents the standardized total effects of the predictors of academic placement. Interestingly, the public reputation of an individual’s academic origin was the only variable with a significant total effect on academic placement public reputation. The public reputation of an individual’s academic origin also had strong total effects on the departmental scholarly output of their academic placement. Pre-appointment publications had a Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 39 Table 4. Total effects of variables on post-appointment publications and post-appointment conference presentations Variables Dissertation advisor research productivity Pre-appointment publications Pre-appointment presentations Academic placement departmental scholarly output Academic placement public reputation Academic origin departmental scholarly output Academic origin public reputation Gender Post-appointment publications Post-appointment conference presentations Years 1–3 Years 4–6 0.21* 0.30* 0.26* 0.16* 0.01 0.08* 0.01 0.01 0.25* 0.13 0.20* 0.18* 0.02 0.06* 0.03 0.06 Years 1–3 0.26* 0.23* 0.30* 0.24* 0.11 0.10* 0.07 0.06 Years 4–6 0.27* 0.09 0.33* 0.23* 0.01 0.09* 0.02 0.06 *p < 0.05. Table 5. Total effects of variables on faculty academic placement Variables Dissertation advisor research productivity Pre-appointment publications Pre-appointment presentations Academic origin departmental scholarly output Academic origin public reputation Academic placement public reputation 0.07 0.03 0.03 0.11 0.53* Academic placement departmental scholarly output 0.03 0.20* 0.15 0.09 0.23* *p < 0.05. significant effect on academic placement scholarly output, but not on the public reputation of an individual’s placement. Advisor research productivity, pre-appointment presentations, and academic origin scholarly output did not have significant total effects on an individual’s academic placement. Discussion In industries where competitiveness is linked to developing new knowledge, organizations must locate and hire individuals who generate high research productivity. Although this selection process is difficult due to the subtle, unobservable traits that make individuals into great researchers, the present study demonstrates that research productivity can be predicted with four theoretical sets of variables. Specifically, results revealed that future research output can be predicted using: (1) dissertation advisor qualifications, (2) graduate school productivity, (3), academic placement, and (4) academic origin. By examining this set of predictors in the context of newly hired management professors, we were able to extend a developing but limited literature on this topic. Thus, one key contribution of this study is revealing the relative importance of advisor qualifications when predicting research productivity. Results indicated that advisor productivity influenced faculty productivity indirectly, primarily through greater publication records as a doctoral student. To illustrate the overall importance of advisor productivity on research productivity during the first six years of their employment, we divided our sample into upper and lower halves based on advisors’ research productivity and compared the average Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 40 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE post-appointment research output of new hires in the resulting groups. Individuals who had an advisor in the lower half of the sample had on average 2.49 presentations and a weighted publication score of 5.38. This was 1.32 fewer presentations and a weighted publication score 4.14 points lower than faculty who were in the upper half of our sample in terms of advisor productivity ( p < 0.01 for both differences). This represents a substantial difference in research output, given that the overall six-year averages for the sample are 2.99 post-appointment presentations and a weighted publication score of 6.96. Thus, our results indicate that early career research productivity was greatly enhanced by studying under advisors who were prolific researchers. Interestingly, previous theoretical models of mentoring and research productivity have tended to not consider advisor qualifications. The findings of this study suggest that the inclusion of this variable when developing models of professionals’ early career productivity may enhance both literatures. The scholarly output of individuals’ academic origin and academic placement were both important predictors of research productivity, supporting the accumulated advantage explanation for why academic affiliation influences research productivity, and showing that management faculty benefit from working in environments that allow them to interact with other successful researchers (Long et al., 1998). We assume that these results generalize to non-academic research settings, such that joining productive research laboratories/units encourages newcomers to be productive too, but future research is necessary to confirm the relationship in other contexts. Consistent with behavior consistency predictions, the research productivity of a graduate student was a significant predictor of his or her early career research productivity as a faculty member. Thus, graduate school productivity serves as a valid signal about individuals’ skills and motivation to continue their research productivity after acquiring a job. As with the accumulative advantage finding discussed above, it would be interesting for future research to examine the extent to which graduate school publications and presentations predicts post-hire research productivity in commercial research settings. Another novel finding of this study is that the predictors of research productivity vary over time. For example, the total effects of pre-appointment publications and presentations on future research productivity were greatly diminished between years 1–3 and years 4–6. This finding suggests that post-hire research behavior becomes less a function of initial success as individuals progress in their careers. Conversely, the total effects of dissertation advisor productivity on individuals’ productivity increased from years 1–3 to years 4–6. One logical explanation for this increased total effect is that the research skills and values that advisors imbued in faculty members increased their research identities as doctoral students, which in turn affected research productivity later in their careers. Thus, the benefits of having a skilled and productive advisor may continue to indirectly affect productivity even when the direct interaction between a protégé and the supervisor decreases. A final finding of interest is the insignificant affect of gender on the post-appointment productivity of faculty members. One explanation that has been used by past researchers to explain gender differences in the performance of professionals is that the mentors of females and males provide different levels of career functions. However, Ragins and McFarlin (1990), in their study of employees in research and development firms, did not find any differences in the roles fulfilled by mentors across male and female protégés. Consistent with their findings, we found an insignificant correlation between gender and dissertation chair advisor research productivity (see Table 2). Thus, it is possible that the early career productivity of male and female faculty did not differ because both groups had equal access to highly qualified dissertation advisors. Limitations and strengths This study has limitations that should be acknowledged. First, we only examined one type of mentoring relationship—the dissertation advisor–student relationship. However, it is likely that individuals Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 41 receive mentoring from people other than their advisor, including former instructors and colleagues within their new job setting, and these relationships also may affect research productivity. Moreover, while the degree to which an advisor can successfully provide career functions to a protégé is somewhat dependent on the advisor’s own qualifications (Kram, 1985), the nature of the interpersonal relationship shared by an advisor and a protégé may also influence the level of career-enhancement provided by an advisor. Previous research has shown that the type and quality of the doctoral student–dissertation advisor relationship varies across participants (Wade-Benzoni & Rousseau, 1998—working paper). Thus, it would be useful for future research to examine whether the nature of the interpersonal relationship between an advisor and their protégé moderates the relationship between dissertation advisor qualifications and early career research productivity. Next, our examination of the relationship between academic affiliation and research productivity considered two of the attributes that have been theorized to influence faculty research productivity: social context and public reputation. However, other aspects of management departments may also influence research productivity, including organizational reward structures and organizational resources (e.g., equipment, research funds). Future research could extend this study by examining the relationships between research productivity and a more comprehensive set of workplace attributes. Related to this point, future research could also examine additional predictors of academic placement. In particular, social network theory suggests that individuals’ job opportunities are in part shaped by their network ties and the ties of those with whom they associate (Granovetter, 1973). For example, protégé’s with dissertation advisors who have extensive connections in the academy may have better employment opportunities than protégés with poorly connected advisors, which in turn may influence early career research productivity. In this study we only examined research productivity in one industry (academia), and in one type of department (management). This focus is useful in that it allows us to study an objective index of research productivity through a common set of journals, and also allows us to build directly on past research (Long et al., 1998; Park & Gordan, 1996). However, it would be interesting to confirm that a similar set of theoretical variables predicts research productivity in other types of academic departments and schools (e.g., schools without doctoral programmes), as well as in commercialized research settings (e.g., software engineering firms, biotechnology research laboratories, management consulting firms). With regard to advisors’ research productivity, for example, on one hand we would expect similar pervasive effects in commercial settings because the advisor is so instrumental in developing a protégé’s ability to conceive and operationalized innovative research ideas. On the other hand, the ability to publish innovative results in academic journals may constitute a different set of skills than the more applied research productivity needed in industry. Thus, the four sets of theoretical predictors examined in this paper may have different weights in terms of predicting applied versus academic research productivity. It would also be valuable for future research to examine whether our theoretical model is applicable in interdisciplinary departments (e.g., Stanford’s programme in Work, Technology, and Organizations) and in international settings. Finally, we only examined one type of individual difference in this study—past research performance. Future research could also expand upon this study by examining other individual-level factors, such as aptitude, previous course work, and motivation. An understanding of how these factors influence early career research productivity could help organizations screen individuals during the recruitment process. Implications The finding that advisor qualifications significantly impact protégé productivity can be looked at in two ways. First, this result suggests that skilled advisors can enhance an individual’s ability to acquire Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 42 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE critical skills early in their careers, thereby increasing a protégé’s early career performance (Kram, 1995). In addition, given that advisors and protégés often possess a great deal of discretion when forming mentoring relationships, this finding can also be interpreted to suggest that highly productive researchers attract better apprentices or perhaps ward off low-quality apprentices. Both interpretations hold important implications for academic doctoral programmes. Given that the goal of many doctoral programmes is to develop effective researchers, universities should employ selective criteria in determining the pool of faculty members from which doctoral students can select dissertation advisors. This may increase the probability that doctoral candidates will receive high quality research training. Furthermore, if prolific researchers are more skilled at identifying highly talented students then less productive researchers, this practice will increase the likelihood that university resources are directed towards those doctoral students with the greatest research potential. Given the importance of research productivity to the competitiveness of firms in knowledge-intensive industries, the findings of this study also hold important implications for organizations attempting to hire productive researchers. In this study, we found that hiring decisions were heavily influenced by the public reputation of an individual’s academic origin, even though this factor was not predictive of future research productivity. Conversely, hiring decisions were not affected by advisor productivity, which had significant total effects on new hires’ research productivity in years 1–3 and years 4–6. Thus, it appears that departments currently are using flawed criteria to hire new faculty, to the extent that they desire research productivity, and results imply that departments should pay closer attention to information about the research productivity of job candidates’ dissertation advisors when evaluating candidate quality. Although additional research is needed to confirm the generalizability of these results, our study implies that non-academic industries also should place greater weight on applicants’ prior research productivity and advisor’s research productivity than the prestige of their university. Finally, our study provides important information to job seekers in the academic labour market. Despite the high correlation between academic placement scholarly output and public reputation (r ¼ 0.48), only the departmental scholarly output of an individual’s academic placement predicted their post-appointment productivity. These results suggest that job seekers should not undervalue employment opportunities in productive departments that may not have the highest external reputation ratings. In other words, job seekers who are motivated to be productive researchers should place more weight on the productivity of a department’s faculty rather than the external prestige rating of the department when making job choice decisions. Acknowledgements We thank Richard Blackburn, Ben Rosen, Ken Smith, and Marcus Stewart for helpful comments on earlier drafts of the paper and Pedro Akl, and Eliot Williamson for their help with data collection. An earlier version of this paper was presented in the Organizational Behavior Division of the 1999 Academy of Management Meeting in Chicago, IL, U.S.A. Authors biographies Ian O. Williamson (PhD, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill) is an Assistant Professor of Management at the Robert H. Smith School of Business at the University of Maryland—College Park. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) EARLY CAREER RESEARCH PRODUCTIVITY 43 His primary research interests include understanding how social network and institutional theories can be used to complement traditional HRM perspectives. He is also interested in examining the recruitment and selection issues faced by small businesses and the use of information technology in HRM. Daniel Cable (PhD, Cornell University) is an Associate Professor of Management at the KenanFlagler Business School at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He also likes to renovate old houses with his wife. His current research interests include talent acquisition and retention, person–organization fit, the organizational entry process, organizational selection systems, job choice decisions, and career success. References Cable, D. M., & Murray, B. (1999). Universalism and the norms of career mobility in science. Academy of Management Journal, 42, 439–449. Coff, R. W. (1997). Human assets and management dilemmas: coping with hazards on the road to resource-based theory. Academy of Management Review, 22, 374–402. Extejt, M., & Smith, J. E. (1990). The behavioral sciences and management: an evaluation of relevant journals. Journal of Management, 16, 539–551. Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Balkin, D. (1992). Determinants of faculty pay: an agency theory perspective. Academy of Management Journal, 35, 921–955. Gourman, J. (1996). The Gourman Report: A rating of graduate and professional programs in American and international universities. Los Angeles: National Education Standards. Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 81, 1287–1303. Green, S. G., & Bauer, T. N. (1995). Supervisory mentoring by advisers: relationships with doctoral student potential, productivity, and commitment. Personnel Psychology, 48, 537–551. Hagel, J., & Brown, J. S. (2001). Your next IT Strategy. Harvard Business Review, 79, 105–113. Hasselback, J. R. (1996). The McGraw-Hill directory of management faculty 1995–1996. New York: McGrawHill. Howard, G. S., Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (1987). Research productivity in psychology based on publication in the journals of the American Psychological Association. American Psychologist, 42, 975–986. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörboom, D. (1999). LISREL 8 user’s reference guide. Chicago: Scientific Software. Kram, K. E. (1983). Phases of the mentor relationship. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 608–625. Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work: developmental relationships in organizational life. Glenview, Il: Scott Foresman. Long, J. S., Allison, P. D., & McGinnis, R. (1979). Entrance into the academic career. American Sociological Review, 44, 816–830. Long, R. G., Bowers, W. P., Barnett, T., & White, M. C. (1998). Research productivity of graduates in management: effects of academic origin and academic affiliation. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 704– 714. Mael, F. A. (1991). A conceptual rationale for the domain and attributes of biodata items. Personnel Psychology, 44, 763–792. Medsker, G. J., Williams, L. J., & Holahan, P. J. (1994). A review of current practices for evaluating causal models in organizational behavior and human resource management research. Journal of Management, 20, 439–464. Merton, R. K. (1973). The sociology of science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Mulaik, S., James, L., Van Alstine, J. Bennet, N., Lind, S., & Stilwell, D. (1989). Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 430–445. Over, R. (1982). Research productivity and impact of male and female psychologists. American Psychologist, 37, 24–31. Park, S. H., & Gordon, M. E. (1996). Publication records and tenure decisions in the field of strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 17, 109–128. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003) 44 I. O. WILLIAMSON AND D. M. CABLE Pfeffer, J., Leong, A., & Strehl, K. (1977). Paradigm development and particularism: journal publication in three scientific disciplines. Social Forces, 55, 938–951. Ragins, B. R., & McFarlin, D. B. (1990). Perceptions of mentor roles in cross-gender mentoring relationships. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 37, 321–339. Rodgers, R. C., & Maranto, C. L. (1989). Causal models of publishing productivity in psychology. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 636–649. Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 224–253. Scandura, T. A. (1992). Mentorship and career mobility: an empirical investigation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 169–174. Scandura, T. A., & Schriesheim, C. A. (1994). Leader–member exchange and supervisor career mentoring as complementary constructs in leadership research. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1588–1602. Soete, C. J. (1995). Guide to doctoral programs in business & management. St. Louis, MO: AACSB. Trieschmann, J. S., Dennis, A. R., Northcraft, G. B., & Niemi, A. W. (2000). Serving multiple constituencies in business schools: MBA program versus research performance. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 1130– 1141. Watson, S. (1998). Getting to ‘Aha!’ Computerworld, 3, 5–10. Wayne, S. J., Liden, R. C., Kraimer, M. L., & Graf, I. K. (1999). The role of human capital, motivation, and supervisor sponsorship in predicting career success. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20, 577–595. Wernimont, P. R., & Campbell, J. P. (1968). Signs, samples, and criteria. Journal of Applied Psychology, 52, 372– 376. Zuckerman, H., & Cole, J. (1975). Women in American science. Minerva, 13, 82–102. Copyright # 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. J. Organiz. Behav. 24, 25–44 (2003)