I nt roduction to Weather Derivatives

advertisement

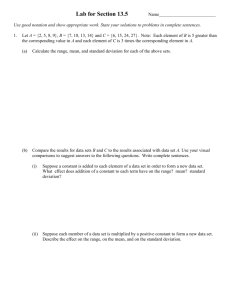

Introduction to

Weather Derivatives

by Geoffrey Considine, Ph.D., Weather Derivatives Group, Aquila Energy

Introduction

The first transaction in the weather derivatives market took place in 19971.

Since that time, the market has expanded rapidly into a flourishing over the

counter (OTC) market. Further growth in the end-user sector is somewhat limited by the credit issues associated with an OTC market (i.e., satisfying the

International Securities and Derivatives Association Master Swap Agreement).

To increase the size of the market and to remove credit risk from the trading of

weather contracts, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) is introducing

weather derivatives to be traded electronically on the CME’s GLOBEX®2

system. The individual contracts are calendar-month futures (swap) contracts on

heating degree days (HDD) and cooling degree days (CDD) as well as options

on futures2. This document discusses some of the fundamentals of pricing and

analyzing weather contracts.

Birth Of A New Market

There are a number of drivers behind the growth of the weather derivative market. Primary among these is the convergence of capital markets with insurance

markets. This process is evidenced by the growth in the number of catastrophe

bonds issued in recent years as well as the introduction of the catastrophe

options that are traded on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT). Weather derivatives are the logical extension of this convergence. The overall growth in the

‘securitization’of risk in the weather and catastrophe markets shows no signs of

slowing. The weather derivative market was jump started during the El Niño

winter of 1997-98, one of the strongest such events on record. This event was

unique in terms of the publicity that it received in the American press. Many

companies, faced with the possibility of significant earnings declines because of

an unusually mild winter, decided to hedge their seasonal weather risk. Weather

derivative contracts are particularly attractive to businesses that have experience

with financial options and futures. The insurance industry was facing a cyclical

period of low premiums in traditional underwriting businesses in this same period and was in a position to make available sufficient amounts of risk capital to

hedge weather risk. The large base of written options from insurance companies

provided the liquidity for the development of a monthly and seasonal swap

market in weather.

1

2

The first weather transaction was executed by Aquila Energy as a weather option embedded in a power contract.

For specifics on the weather contracts, visit the Chicago Mercantile Exchange’s Web site http://www.cme.com/weather/index.html

1

Hedging Weather Risk

A company has a number of alternatives in structuring a weather deal. The first

alternative is most similar to an insurance product — to buy a cooling degree

day option (CDD) in the case of summer, or a heating degree day option

(HDD) for winter. The number of cooling degree days on a single day is the difference of the daily average temperature from 65 degrees Fahrenheit. Cooling

degree days and heating degree days are never negative. If the daily average

temperature is less than 65 F, then the difference of the daily average temperature and 65 F is the number of HDDs. Over the course of a month, one might

accumulate both CDDs and HDDs. Weather options are written on the cumulative HDDs or CDDs over a specified period. The CME contracts therefore are

based on the total number of HDDs or CDDs in the month.

Beyond the insurance-like purchase of a call or put option, a business with

weather exposure may choose to buy or sell a futures contract, which is equivalent to a swap such that one counter party gets paid if the degree days over a

specified period are greater than the strike level, and the other party gets paid if

the degree days over that period are less than the strike. A business may also

choose to write an option. A heating oil retailer may feel that if the winter is

very cold they will have high revenues — so they might sell an HDD call. If

the winter is not particularly cold, the heating oil retailer keeps the premium on

the call. If the winter is very cold, the retailer can afford to finance the option

pay out with higher-than-normal revenues.

A customer may wish to buy a strip of CDD or HDD contracts spanning the

entire cooling season of April through October. Each contract has a specified

strike for each month. Each option is listed with a price for each range of

strikes. In the OTC market, it is common for options to be written on a multimonth period with a single strike over the entire period. The benefit of buying a

strip of monthly contracts is that the strip can be broken apart more readily than

a single, longer-term contract. The simplest approach is to purchase a strip of

call or put options over the range of months that are of interest to the user. As

one intuitively expects, the further out of the money (i.e., away from normal

conditions) the strike is set, the lower the price of the option (the premium).

The strike is set relative to the normal climatological values. The normal value

is a matter of debate. The market currently seems to be converging on the average over the past 10-15 years. Clearly there are many cases in which the 15year average may not be ideal. Miami, for example, has shown a substantial

warming trend over the past 30 years, such that 15-year average CDDs in summer are less than one may expect. Of course, the market will have factored the

trend into the pricing of the option. A CDD call option will thus appear quite

expensive if the option is simply priced at the 15-year average. Conversely, a

CDD put option will appear to be inexpensive in this scenario.

To date, utilities have been the largest end-users of weather derivatives.

However, there are many other businesses in which weather has a major impact

on revenues. It is anticipated, for example, that positions in agricultural commodities will be hedged with weather contracts more extensively than power

and gas positions because of the long series of historical data available in the

2

agricultural markets. Because growing degree days and cooling degree days are

very similar, standard weather contracts could be used to hedge commodity

price risk. One of the CME-listed cities is Des Moines, and we present some

calculations that demonstrate how a considerable fraction of the volatility of

corn prices in Iowa could be hedged using weather options. The challenge in

such cross-commodity hedges is the development of appropriate weather pricing models.

Simple Option Pricing

Simple pricing models can be constructed using a probability distribution fitted

to an historical data set of monthly CDDs or HDDs, and integrating the product

of the probability distribution with the payoff of the option. The expected payoff of a CDD option, or its theoretical value, is simply determined by:

E=M

P(CDD)Q(CDD)d(CDD)

where P(CDD) is the probability distribution of CDDs, Q(CDD) is the payoff of

the option in units of CDDs, M is the number of dollars specified in the contract per CDD, and d(CDD) is the differential. The expected value changes as a

function of the strike, the probability distribution of CDDs, and the number of

dollars per CDD.

We begin with an example for an HDD put option for Las Vegas for the period

from Nov. - March. With a mean value of 1,933 HDDs for this period (detrended), we choose a strike of 1,833 to yield the following structure:

3

We have drawn this option (see figure on the preceding page) with $5,000 per

HDD and a premium of $200,000 for demonstration purposes. At this level, the

buyer owns an option with an expected value (expected payoff minus premium)

of about $24,000. The price of this option was derived from a simple pricing

model that is discussed below. We discuss a number of the key problems associated with arriving at such a price.

Pricing weather options requires an historical temperature database and application of statistical methods for fitting distribution functions to data. Historical

data is available from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA), and many inexpensive statistical packages can be used to examine the

statistical distributions in a dataset. The Chi-square and Kolmogorov-Smirnoff

tests are two of the most common methods for evaluating a good fit in this type

of problem. In many cases, the probability distribution of CDDs and HDDs can

be fitted using a Gaussian (normal) distribution. The Midwestern Climate

Center (MCC) has an online subscriber database that provides monthly-total

CDDs and HDDs for all U.S. cities and provides a useful resource for those

participating in the market. Be aware, however, that the standard used to calculate CDDs and HDDs is different in the weather market than what is used by

the atmospheric community such as the National Weather Service (NWS) and

NOAA. The NWS rounds the average daily temperature to the nearest degree

for each day, whereas the weather market does not round temperature and keeps

one decimal place in the daily CDDs or HDDs.

There are a number of complications in the pricing process. First, a simple distribution should not be fitted directly to the historical data. Many measurement

sites in the U.S. exhibit significant long-term (multi-decade) trends and other

variability. This variability must be accounted for in a pricing model. The

Center for Climate Prediction provides data on long-term trends across the

United States at fairly coarse resolution. These trends cannot be used directly,

however, because weather derivatives are struck based on a single NWS measurement site — and a site at the end of an airport runway may exhibit different

long-term trends from the region surrounding it. In short, there is a need to

carefully analyze the history of the specific station in question. The station data

may be poor, the tower may have been moved, or the instrumentation may have

changed.

The Gaussian Pricing Model

A very simple, and quite often sufficient, formula for pricing individual options

can been derived for the case of a Gaussian distribution of CDDs or HDDs.

Assuming that one knows the mean (average) and standard deviation of CDDs

or HDDs in a location, it is simple to approximate the price of an option. The

algebraic expression in the figure on the following page relates the price of an

option to three factors:

1. The standard deviation of the distribution;

2. The distance of the strike from the mean value;

3. The number of dollars per degree day specified in the contract.

4

If we define a normalized strike in terms of the number of standard deviations

of the strike away from the mean value, the cost of the option is easily calculated from the relationship below:

Consider an option over a period for which the standard deviation of CDDs is

100 CDDs, with a mean value of 1,000 CDDs, and we define the strike for the

option to be at 1,080 (i.e., this is a CDD call), with a specification of $5,000 per

degree day. The strike is 0.8 standard deviations out from the mean. Using the

equation above, we determine that the value on the vertical axis corresponds to

0.125. To obtain the expected value of the option, we simply compute the

product:

Option Value ($) = $5,000 x 0.125 x 100 = $62,500

Note that this expected value does not include the “risk premium” that the

writer of the option charges for carrying the risk. Nevertheless, this simple formulation provides a baseline from which to price an option.

Clearly the largest challenge facing the options market participant is

determining the mean and standard deviation to use as the model input.

For many contracts, we have found that a Gaussian distribution is quite

sufficient. Assuming that a Gaussian is acceptable, where do we get the

mean and standard deviation?

5

Obtaining The Inputs To The Pricing Model

Defining an appropriate mean and standard deviation is the key challenge in

simple-option pricing. Do we use the last 10 years? The last 20 years? How

about 50 years? The problem is that climate is non-stationary, which is to say

that the relevant mean and standard deviation evolve with time. This problem is

well known among climate researchers who have struggled to determine the

Optimal Climate Normal (OCN), or the optimal average time scale of previous

years for determining the expected value for this year. The National Center for

Environmental Prediction (NCEP) runs an operational tool that is a simplified

OCN calculation. This product examines whether the previous 10 years are a

better climate predictor than the defined “climate normal period” of 1961-1990.

Where the historical data indicates that the previous 10 years provides an

improved estimate, this 10-year average is used. One of the primary drivers that

makes the previous 10 years a better predictor than the period from 1961-1990

is large trends in urbanization. Any city that has a strong warming trend will be

better approximated using the most recent 10 years than using NCEP’s 30-year

normal. An interesting issue is that the concept of OCN has not been defined

for determining the standard deviation of the degree days in different regions.

The simplest source for tackling the problem of “normal” climate conditions is

the National Climate Data Center (NCDC). The Midwest Climate Center

(MCC) has an online service where one may download daily average temperatures for specific stations, as well as a range of other climate data, using the

NWS standard for degree days. With regard to this issue, the traded contracts

are referenced to a specific measurement station of the National Weather

Service. Each station has a unique NCDC number used to identify it in databases such as MCC. NCDC also publishes archives of historical temperature

and precipitation data at US stations on CD ROM.

OCNs are not necessarily ideal in determining expected values in pricing

options. There are many ways to correct for non-stationary climate data. The

first step is to correct for trends, but the climate record contains variability on

many time scales: from a few years to decades and longer. During an El Niño

year, for example, it would be very important to understand how El Niño skews

the climate statistics in the region of interest. For many seasonal contracts, the

Gaussian model will be sufficient if one can obtain a good estimate of the mean

and standard deviation of degree days.

The current long-range forecasts have quite limited accuracy. NCEP provides

seasonal forecasts using a range of tools. The market makers in the weather

market have proprietary long-range forecasts of varying levels of sophistication.

Further, many commercial forecast services produce long-range forecasts. It is

important to note that many long-range forecast products are of dubious quality.

In general, we have found that most commercial forecast providers cannot

quantify whether they have any forecast skill at all.

6

The Value Of A Strip Of Options

One obvious question at this point is how to relate the value of a strip of monthly options to the value of a single option for a multi-month period. Consider a

two-month HDD contract for January and February. Assume that we have a

location for which we know the following:

Average (Mean)

Standard Deviation

January HDDs

400

100

February HDDs

300

80

If we wish to protect ourselves against a Jan. - Feb. period with more than 790

HDDs, what do we do? We could buy one Jan. and one Feb. HDD call option.

The strike on the Jan. option would be 450 HDDs and the strike on the Feb.

option would be 340 HDDs (i.e., we have placed the strike at one-half a standard deviation out on each option). How about if we wanted to buy a single

option for the entire period? The average of the HDDs over the period is the

sum of the averages (i.e., 700 HDDs). The standard deviation over the Jan. Feb. period is not the sum of the standard deviations. If the standard deviation

of January is defined as SD(Jan.), and the standard deviation of February is

defined as SD(Feb.), the standard deviation of Jan. + Feb. is given by:

SD(Jan.+ Feb.) = {SD(Jan.) 2 + SD(Feb.)2 + 2rSD(Jan.)SD(Feb.)}1/2

where “r” is the correlation between the number of HDDs in January and the

number of HDDs in February.

If we assume that the number of HDDs in February is not correlated to the

number of HDDs in January (an issue that would be decided using historical

data), the standard deviation of the two-month period is 130 HDDs. Our twomonth option would thus have its strike at 0.7 standard deviations away from

the mean (i.e., our strike is at 790 HDDs and one standard deviation away from

normal is 830 HDDs). Let’s assume that we wish to be paid $5,000 per HDD

above the strike. The expected value of the two month option is:

Value of Jan. - Feb. HDD Call = 0.148 x 130 x $5,000 = $96,200

whereas the value of the option priced individually is:

Value of Jan. HDD Call = 0.201 x 100 x $5,000 = $100,500

Value of Feb. HDD Call = 0.201 x 80 x $5,000 = $80,400

The cost of buying the pair of options is $180,900.

The difference in price between buying two monthly options versus a strip that

includes both months reflects the probability of the associated anomaly occur-

7

ring in the entire two-month period and anomalies occurring in either one or

both of the individual months. The relationship between pricing at different

time scales can discover fundamental pricing disparities in weather contracts. A

major utility recently found that it was cheaper to cover their winter season by

buying a series of monthly contracts rather than buying a single contract for the

whole season. In this situation, the market had not efficiently priced the risk

associated with these options. A market participant who bought the individual

months and financed this purchase by selling a single contract for the entire

period should reap a significant profit in this situation.

This brief discussion of some of the challenges in pricing weather derivatives

suggests that care must be taken in the theoretical pricing of these options. As

the exchange-traded market gets underway, the market will increasingly provide

price discovery so that in-depth analysis is not required of all participants.

There are a number of market makers who have been working these issues

extensively in the OTC market — and the price-discovery function of these

large players is already evident in weather option prices.

Basis Risk

While the OTC weather market includes most U.S. cities, the CME market will

initially include only eight or ten cities. This means that participants wishing to

purchase weather coverage in cities not listed by the CME face basis risk,

which is the risk due to the contract being written in a different location than

the area which the user wishes to cover. The “basis” between cities is the difference in CDDs or HDDs between cities. Basis can be traded, such that a contract

might be written on the difference between CDDs in Birmingham and Atlanta

in a given period of time. For a variety of reasons, the relationship between

CDDs in Atlanta and CDDs in Birmingham changes over time, and this temporal variability must be accounted for.

One of the challenges of weather derivatives is that climatic variability occurs

on spatial and temporal scales that lead to a strong correlation between many

locations. The spatial and temporal relationship between sites occurs on a wide

range of scales such that two locations may be well correlated on a weekly time

scale but not so on a monthly time scale.

Hedging With Weather Options And Swaps

The great appeal of weather derivatives is that they can be used to hedge risks

in other components of an investment portfolio. Many businesses are exposed

to weather risk of some kind. The challenge in hedging is to cover these risks in

an effective manner. There is a great deal of discussion about using weather

options to hedge weather risk in energy markets, for example. Some care is necessary in building a net position containing a physical commodity, such as gas

or power, along with weather options. In this case, weather options are a hedge

on volume, not on price.

While there is obviously a relationship between consumption volume and price,

the relationship is not one-to-one. The capacity to store natural gas is such that

8

high demand may or may not lead to an increase in price in the near term. If

there is a large amount of gas in storage and the weather in winter turns cold, an

end user might draw from storage if the price of gas on the spot market is high.

In the electrical power market, there is no storage and price is much more sensitive to forecasts of unusually warm or cool weather. Still, the connection

between price and volume consumed involves some uncertainty, with production capacity being a key. If a nuclear reactor in a region is off line and

extremely warm weather appears in summer, the price of electricity in that

region may jump sharply. The ability to change net production is a key consideration that complicates the relationship between electricity price and weather.

The challenge in using weather options as a cross-commodity hedge is in deciding the model risk inherent in determining the fraction of risk that can be effectively hedged using a weather contract. This problem is not limited to power

and gas. In agricultural markets, common wisdom suggests that weather derivatives could be used to hedge yield, but not price. Statistical models can be

developed to couple weather risk to agricultural price risk. Great care must be

taken to determine the effectiveness and quality of the coupling model. As an

example of a possible hedge associated with corn price, we present an analysis

of the change in corn price from March to November in Iowa. Using multiple

linear regression, we have found that a large fraction of the variability in the

change in corn prices from March to November can be explained by cooling

degree days in Des Moines for two months.

The figure below shows the change in the price of Iowa corn from April to

December (black line) from 1958-1997. The grey line shows a model fitted to

9

these price changes in terms of four variables: a trend in time, April price, July

CDDs in Des Moines and August CDDs in Des Moines. All four of these variables are statistically significant in explaining the variability in corn price.

August is more significant as a predictor than July. From these results, it is

clearly possible to hedge changes in corn price using Des Moines CDD monthly contracts. This model is highly statistically robust. We note that there is also

a strong mean-reverting behavior in this model such that the correlation

between the Dec. - April price change is negatively correlated with April price.

If one were seeking to hedge against volatility in corn prices, weather derivatives may be an attractive avenue, depending upon the relative pricing of corn

futures and options, and weather swaps and options.

Conclusions

There are many challenges to the effective use and management of weather

options, and we have detailed a few of them. Pricing models for weather derivatives exist at many levels of sophistication and the simple analytical model

shown here is not necessarily what the market makers use. This said, a simple

model can give a rough idea of what an option should cost. Weather derivatives

can be very useful to risk managers who understand options and the risk profile

associated with buying and selling weather options relative to their business. It

is fairly straightforward to add weather options to a Value At Risk (VAR) calculation. There is a range of interesting complications, however, in adding weather options to a portfolio that already contains risks correlated to climatological

variability.

While the CME is listing only CDDs and HDDs, Aquila can structure OTC

contracts on rain, snowfall, wind, etc. For more information on such meteorological variables, please contact the Aquila Energy weather desk using the contact information below.

Potential participants in the weather market would be well advised to become

acquainted with the useful resources provided online by the National Weather

Service, and programs by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric

Administration such as the Climate Prediction Center (CPC) and the Climate

Diagnostics Center (CDC).

For more information about weather derivatives, please contact the

Aquila Energy weather desk at: 1-800-891-3687 or visit our Web site at

www.aquilaenergy.com/guaranteedweather.htm

10