Litigation over the Rights of "Natural Lords"

advertisement

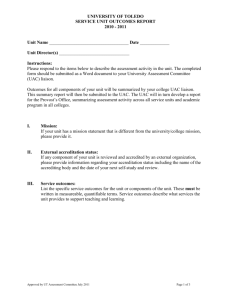

This is an extract from: Native Traditions in the Postconquest World Elizabeth Hill Boone and Tom Cummins, Editors Published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 1998 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html Litigation over the Rights of “Natural Lords” Litigation over the Rights of “Natural Lords” in Early Colonial Courts in the Andes JOHN V. MURRA INSTITUTE OF ANDEAN RESEARCH I N THE EARLIEST DAYS OF THE EUROPEAN INVASION, when Inka resistance, potentially so threatening, turned out to be virtually absent (Lockhart 1972), the Pizarros acquired a steadfast ally, the Wanka lords. It was in their territory, Xauxa, that the Europeans established their first capital. Along with thousands of soldiers and bearers, the Wanka provided the newcomers with strategic information, plus the food and weapons stored in hundreds of warehouses built by the Inka and filled locally (Polo de Ondegardo 1940 [1561]). In one region where the Inka had managed to cobble together some resistance, as at Huánuco, the Europeans had to call on Wanka troops to help them put down “the rebellion.”1 All this assistance provided the Europeans was recorded with care on a khipu kept by the Wanka lords. This record was first described by Cieza de León, some fifteen years after the invasion. Such bookkeeping later became the subject of litigation initiated at the viceregal court, at Lima, by one of the lords who in 1532 had opened the country to the troops of Charles V (Murra 1975). This man, don Francisco Cusichac, felt betrayed by the ill-treatment of his people and the neglect of his own privileges. The notion that his Wanka, and he along with them, were to be granted in encomienda to some European newcomer was shocking; Cusichac reasoned that if there were to be any encomenderos about, he, Cusichac, was the most appropriate candidate (Espinoza Soriano 1972). By 1560 the Wanka had made many adjustments to European rule. The most notable was the intensive training of their sons in the new language and beliefs. Several of these bilingual young men, accompanied by their own, European-style notaries, traveled to Spain to petition at court for reward of 1 An Inka “general,” Ylla Thupa, withdrew to the Huánuco region and managed to hold out there for almost ten years. He was smoked out by Wanka auxiliary troops (Ortiz de Zúñiga 1967). 55 John V. Murra past services from the emperor or his son (Espinoza Soriano 1972).2 Some of these “natural lords” were received by the monarch; some were granted coats of arms Spanish style. One of the petitioners requested that the crown grant him the right to sell and buy land, a privilege unknown in the Andes. By 1570, when the new viceroy, Francisco de Toledo, decided to conduct an inspection of the crown’s highland provinces, don Francisco Cusichac and his whole generation was dead. Their sons were now in charge, some of them very young men who some fifteen years earlier had met Charles V or his son, Philip, in Europe. The new viceroy called on all native authorities to display their European credentials and many did. Toledo ordered that the assembled parchments be burned. This was the beginning of a campaign against those lineages in the Andean elite that had collaborated with the invaders, an effort to destroy the European evidence of what the Spanish crown had once bestowed.3 The only other group to be treated so harshly by Toledo were the descendants of another wing of the Andean elite who also sided from the earliest days with the invaders. These were the “sons” and heirs of Pawllu Thupa, the one Inka “prince” to make peace, early and openly, with the Europeans. Pawllu had helped them through extreme difficulties, particularly Almagro’s invasion of Chile. The efficiency of that thrust south was attributed by many to Pawllu Thupa’s ability to mobilize the lords of Charcas, the region known today as Bolivia.4 For his services, Pawllu had been allowed to keep “his Indians,” coca-leaf terraces, food-producing fields, and much other Inka wealth. A test came in 1550 at Pawllu’s death: various Europeans attempted to deprive the “Indian’s” heirs of these lands and people, but the emperor’s representative, Bishop LaGasca, resisted such claims. For the next two decades, Pawllu’s many sons were a distinguished and rich lineage in Cuzco. They spoke Spanish, invested in the long-distance coca-leaf trade to the mines at Potosí, and employed Europeans in their various enterprises. The main heir, don Carlos, was married to a European woman.Thirty-five years after the invasion, Pawllu Thupa’s heirs were the one group of Inkas at Cuzco who had managed to hang on to both status and wealth (Glave 1991). When Toledo reached Cuzco on his way to the mines at Potosí, he selected Pawllu’s lineage for special attention. As at Xauxa, the lords were ordered to 2 These grants are transcribed from the originals in the Archivo General de Indias, Seville: section Lima, legajo 567, lib. 8, fols. 107v–108r; see also other grants cited by Espinoza Soriano (1972). 3 Letters from Francisco de Toledo to Philip II, found in the Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid. 4 See Pawllu Thupa’s testament published in Revista del Archivo Histórico del Cuzco (1950: 275, 286). 56 Litigation over the Rights of “Natural Lords” display the credentials testifying to their services to the Spanish crown. The papers were publicly burned. Don Carlos and his kin were accused of maintaining illicit contacts with those Inka who had taken refuge at Vilcabamba, in the eastern lowlands (Kubler 1946). Some twenty of Pawllu Thupa’s heirs were put on trial for subversion; during the proceedings, which lasted many months, the princes were kept in animal corrals, exposed to the elements.The testimony was conducted in Quechua even though many of the accused spoke Spanish; a mestizo, one Gonzalo Gómez Ximénez, “interpreted” for the only record kept of the proceedings, despite continuous protests by the accused. Ximénez’s version of what they had “confessed” became the official transcript. The “natural lords” were sentenced by Gabriel de Loarte to the loss of “their” Indians and of their coca-leaf fields, which were granted by Toledo to Loarte. Some twenty Inka, including aged princes, don Carlos, and several children, were deported on foot to Lima. From there they were supposed to be shipped into exile to Mexico.5 Of the twenty, seven survived.They were able to rally support from some of the judges at the Audiencia who were hostile to the viceroy. Toledo remained in the highlands for almost another decade, the only viceroy to devote such personal attention to the Andean population. He sponsored many institutional innovations; some of them were consistent with ideas to end the Las Casas “benevolent” approach to Indian affairs, which he brought with him from court. He tried to put an end to the influence of Bishops Gerónimo de Loaysa of Lima and Domingo de Santo Tomás in Charcas, men from another era, who spoke Quechua and had earlier corresponded with Las Casas (Las Casas 1892). Of the people Toledo consulted, the best informed were two Salamancatrained lawyers—Juan de Matienzo and Juan Polo de Ondegardo—who gave him diametrically opposed advice. Matienzo, a crown justice at the Audiencia of Charcas, was frequently active away from his court. Even before Toledo’s arrival in 1569, Matienzo had argued for the “extirpation” of the Inka lineage that had taken refuge in the forest at Vilcabamba. The high court in Lima was betting on a reduction policy, resulting in the conversion of the refugee princes and their resettlement at Cuzco. Matienzo thought such a policy was dangerous. Resettlement expanded the number of “natural lords” at Cuzco—a loss of revenues for the Spanish crown and the threat implicit in an additional focus of traditional loyalty (Matienzo 1967). After Toledo’s arrival, he and Matienzo formed an intimate alliance broken only by the judge’s death in 1579. 5 Most of this material comes from the Justicia legajo 465, a three-volume manuscript record of the litigation in Mexico, Archivo General de Indias, Seville. Some of it is quoted by Roberto Levillier (1921–26). 57 John V. Murra Matienzo had provided Toledo with a working understanding of the Andean system; it was Matienzo who designed the rotative mita system for recruiting the Andean labor force for the silver mines at Potosí, which was based on the Inka mit’a set up for the state cultivation of maize (Wachtel 1982). All efforts now were directed to improve the revenues of King Philip’s armies—be these active in Flanders or facing Constantinople by sea. Though trained at the same law school as Matienzo and proceeding from much the same social background, lawyer Polo de Ondegardo had a very different vision of the Andean world. One dimension of this perception was his much longer service in the region: he had arrived in 1540, some twenty years before Matienzo, at a time when Andean society was much closer to its aboriginal condition. He also never joined the court system, but held a variety of posts that brought him into daily contact with Andean realities: soldiering in the infantry, administering the newly discovered mines at Potosí, tracing the royal lineages at Cuzco, facing the dangers of lowland coca-leaf cultivation for highlanders, recognizing that ethnic groups resident at 3,800 m up in the Andes would also control people and fields at sea level. He noted the remarkable warehouse system continuously filled along the Inka highway; in pre-Toledo times he was frequently consulted by viceroys and settlers alike. He had no ideological difficulty in recognizing that the descendants of King Thupa or of Wayna Qhapaq were, according to European rights, “natural lords.”6 While the two Salamanca alumni avoided head-on collisions, Polo did turn down the nomination by Toledo to repeat as governor of Cuzco. Unhappy with many of the decrees issued by the viceroy, Polo composed a book-length memorandum addressed to Toledo: “a report about the premises which lead to the notable harm which follows when not respecting the fundamental rights of the Indians . . .” (Polo de Ondegardo 1916 [1571]). In it he also argued against the resettlement policy dictated by Matienzo and Toledo: when resettled into compact reducciones, the ethnic groups were impoverished since they lost access to their outliers located at many faraway resource bases. Even should one want to make Christians of them, argued Polo, it is best to proceed taking into account their own “order.” Further clarification of this transitional period in Andean history came through my recent, 1990–91, “discovery” in the Archive of the Indies in Sevilla of a large (3,000–plus pages) set of files recording in detail the minutes of the trial at Cuzco of the “natural lord” don Carlos Inca. While this source had been quoted in print as early as the 1920s by the Argentine scholar Roberto Levillier (1921–26, 7: 192–193), it had remained 6 58 See details in Murra 1991. Litigation over the Rights of “Natural Lords” underutilized by anthropologists. It greatly expands our understanding of Cuzco social structure a generation after the invasion. There is much detail about the kangaroo court run by Toledo and his chief aide, Judge Gabriel de Loarte. The doctor “inherited” the estates and subjects of the defendants. The later career of the interpreter, Gonzalo Ximénez,7 is also noted: a few years later he was burned at the stake in Charcas, accused of the pecado nefando, the abominable sin of homosexuality. The Inka princes had raised the issue unsuccessfully throughout their “trial.” While awaiting his fate in the Charcas jail, Ximénez is said to have expressed a desire to confess his perjury and to apologize for the harm done to don Carlos. Ximénez is alleged to have recorded this wish in writing. This confession has not been located in the Audiencia of Charcas papers; Dr. Barros de San Millán, a judge at that royal court, is said to have expressed a lively, if suspect, interest in locating this document, without success. Barros deserves the attention of anthropologists interested in Andean history. Trained at Salamanca, as were our two other lawyers, his American career spans close to thirty years, serving at the royal courts of Guatemala, Panamá, Charcas, and Quito. Our first notice of him in Andean scholarship reached us a few decades ago, when Waldemar Espinoza, a Peruvian colleague, published an Aviso, author unknown. It was a petition, signed by a dozen or so ethnic lords of Charcas (today Bolivia) (Espinoza Soriano 1969); addressed to the king, it seemed to be dated from a moment late in Toledo’s reign. In it the Andean lords trace their lineages four or five generations back, when the Inka were alleged to have granted their ancestors lavish textiles and wives from court: “we were the dukes and the marquesses of this realm.” They offered to assume additional duties at the Potosí mines but did not care to be assigned only labor-recruiting duties. The argument that they were “natural lords” was now restated away from Cuzco and under new colonial circumstances. The author of the memorandum remained unidentified for decades. It was clear that he was familiar with both administrative procedures at the mines and with the ethnic map of the southern Andes; he plainly enjoyed the trust of the Aymara lords.The memorandum has recently been the object of detailed study by a Franco-British team preparing a documentary collection to honor don Gunnar Mendoza, director of the National Archive of Bolivia.They eventually decided that the author was the very person disguised in the Aviso as the transmitter of the text to the court at Madrid. Between his service at Charcas and 7 Much of this material is to be found in legajo 844A of the branch Escribanía de Cámara, Archivo General de Indias, Seville. 59 John V. Murra his return to the Americas as chief judge at Quito, Barros spent some years in Spain. His activities there and his ideological connections have not been fully ascertained. The identification of Barros as the author of the Aviso is reinforced by events at the royal court of Charcas in the waning years of Toledo’s regime.8 A year or two before the judge’s return to Madrid, Barros was charged by his fellow judge at the Charcas royal court, Matienzo, with being a homosexual. At that point, in the late 1570s, the court was down to just two judges, Matienzo and Barros. If one of them became the accused, the tribunal would be down to only one justice. In a plainly illegal maneuver, Matienzo co-opted two residents of Charcas as assistants; Barros took refuge in one of the monasteries at La Plata, but if that charge had prevailed, the Franciscans could not have protected him. The testimony was sworn to by a pickup crew: none of the important encomenderos took part. Witnesses remembered that “the doctor” had freed the slaves he had brought with him from Panamá; one of the clerks testified that when he went to the judge’s quarters for a signature, he found el doctor entertaining unceremoniously in his kitchen a group of “Indian” chiefs. The freed Africans were also about. Another clerk thought the doctor talked too much and did not keep secret positions assumed about the court in camera. Other witnesses, from the mining center at Potosí, stressed his homosexuality and his careless approach to His Majesty’s interests at the mines. Barros is also reported to have searched for interpreter Ximénez’s confession to show that he had perjured himself during don Carlos’ interrogation at Cuzco. Barros is quoted as saying that the viceroy had not only appropriated the Inkas’ fields, but he was now ready to destroy their good name. While all this was going on, in 1579, Matienzo died. Barros emerged from hiding and, as sole justice in the region, assumed possession of the royal Audiencia. An attempt was made by the Potosí miners to continue the trial somehow, to reach a conviction. They petitioned the viceroy who was now in Lima, awaiting permission from the crown to return to the peninsula. Toledo answered that the Charcas court was down to a single justice, Barros. The proceedings against him were dropped. As soon as he reached the Charcas court, Barros took an important step. One of the most resented measures taken by Toledo, with Matienzo’s connivance, had prohibited forwarding on appeal to the peninsula of Andean cases heard at the Charcas court.Thousands of pages and transcripts of cases pending 8 Details in legajo 844A of Escribanía de Cámara, Archivo General de Indias, Seville. Also fol. 9r of Charcas 16, ramo 15, fol. 3v. 60 Litigation over the Rights of “Natural Lords” had not been forwarded to Madrid. All this was now dispatched to the crown. Soon after, Barros returned to Spain, for the first time in twenty or so years, presumably carrying with him the Aviso. 61 John V. Murra BIBLIOGRAPHY ESPINOZA SORIANO, WALDEMAR 1969 El memorial de Charcas: crónica inédita de 1582. In Cantuta. Revista de la Universidad Nacional de Educación, Chosica, Perú. 1972 Los Huancas, aliados de la conquista. Anales Científicos de la Universidad del Centro del Perú 1: 201–407. Huancayo. GLAVE, LUIS MIGUEL 1991 La hoja de coca y el mercado interno colonial. In Visita de los valles de Sonqo ( John Murra, ed.): 583–608. Instituto de Cooperación Iberoamerica, Madrid. KUBLER, GEORGE 1946 The Quechua in the Colonial World. In Handbook of South American Indians, vol. 2 ( Julian H. Steward, ed.): 331–410. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. LAS CASAS, BARTOLOMÉ DE 1892 Las antiguas gentes del Perú. In Colección de libros españoles raros o curios, vol. 21 (Marcos Jiménez de la Espada, ed.). Madrid. LEVILLIER, ROBERTO (ED.) 1921–26 Gobernantes del Perú. 14 vols. Vols. 1–3 published by Sucesores de Rivadeneyra, vols. 4–14 published by Imprenta de Juan Pueyo. Madrid. LOCKHART, JAMES 1972 The Men of Cajamarca: A Social and Biographical Study of the First Conquerers of Peru. University of Texas Press, Austin. MATIENZO, JUAN DE 1967 Gobierno del Perú [1567] (Guillermo Lohmann Villena, ed.). Institut Français d’Études Andines, Paris-Lima. MURRA, JOHN V. 1975 Las etnocategorías de un khipu estatal. In Formaciones económicas y políticas del mundo andino: 243–254. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Lima. 1991 Le débat sur l’avenir des Andes. In Culture et sociétés andes et méso-amérique, vol. 2 (Raquel Thiercelin, ed.): 625ff. ORTIZ DE ZÚÑIGA, IÑIGO 1967 Visíta de la provincia de León de Huánuco en 1562, vol. 1: 312. Facultad de Letras y Educación, Universidad Nacional Hermillo Valdizán, Huánuco, Peru. POLO DE ONDEGARDO, JUAN 1940 Informe al licenciado Briviesca de Muñatones . . . [1561] Revista Histórica 13: 120–196. Lima. 1916 Relación de los fundamentos acerca del notable daño que resulta de no guardar a los yndios sus fueros . . . [1571] In Coleccíon de libros y documentos referentes a la historia del Perú, ser. 1, vol. 3. Imprenta y Librería Sanmartí y Cia., Lima. REVISTA DEL ARCHIVO HISTÓRICO DEL CUZCO 1950 Revista del Archivo Histórico del Cuzco 1: 275, 286. WACHTEL, NATHAN 1982 The Mitimas of the Cochabamba Valley (George A. Collier, ed.). In The Inca and Aztec States, 1400 –1800: Anthropology and History: 199–236. Academic Press, New York. 62