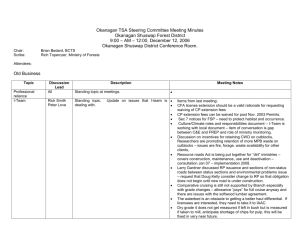

Report 407 - Professional Planner

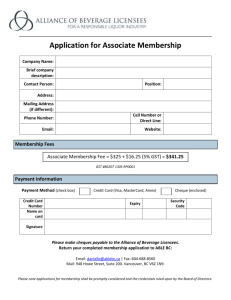

advertisement