The University of Newcastle

Faculty of Education and Arts

School of Humanities and Social Science

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/school/hss/

Callaghan Campus

University Drive,

Callaghan 2308

NSW Australia

Office hours: 9am-5pm

Room: MC127 McMullin Building

Phone: +61 2 4921 5175/5172/5155

Fax: +61 2 4921 6933

Email: Humanities-SocialScience@newcastle.edu.au

Web: http://www.newcastle.edu.au/school/hss/

HIST 3670

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION AND NAPOLEON

COURSE OUTLINE

Course Co-ordinator:

Room:

Ph:

Fax:

Email:

Consultation hours:

Dr. Philip Dwyer

MCLG22b

49215211

49216933

Philip.Dwyer@newcastle.edu.au

Monday, 9am-12am

Semester

Unit Weighting

Teaching Methods

Semester 1, 2007

20

Lectures and Tutorial

Background

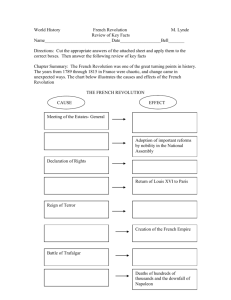

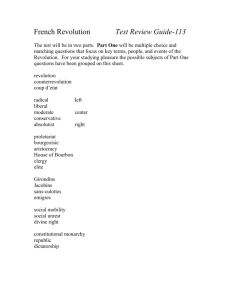

This course provides a comprehensive overview of the origins and development of

the French Revolution and Napoleon, from the end of the Ancien Regime (1788) to

the fall of Napoleon and the battle of Waterloo (1815).

The Revolutionary era is one of the most exciting periods in Modern European

History. It is also one of the most controversial and most written about. Unlike the

revolutions that took place in England and America, the French Revolution had

enormous political and social consequences outside of the country in which it took

place. Europe and the world still reverberate to the sounds of the “Marseillaise” and

the Declaration of the Rights of Man, and they still talk about Napoleon Bonaparte.

This course focuses not only on the political and social changes which took place in

France during the revolutionary period, but also the changes that occurred as a result

of the Revolution being taken abroad, first by the revolutionaries then by Napoleon.

As a side issue, this course also examines “revolutions” in a more general sense —

why do they take place, who takes part in them, do they always degenerate into

violence and how do they end?

A twenty unit course has four contact hours per week. There are two, one hour

lectures, and one two-hour seminar.

Course Outline Issued and Correct as at: Week 1, Semester 1 - 2007

CTS Download Date: 30 January 2007

1

Lectures

Monday, 1.00-3.00 pm, Mc132

Seminars

Tuesday, 9-11 am, Mc110

OR

Tuesday 11 am-1 pm, Mc110

Seminars and group work form the most important part of the course. They look at a

selection of themes and problems, and are the equivalent of practical work in

chemistry. They are your chance to experiment, to work out your ideas, to put

different elements of a problem together — who knows, you may even cause some

explosions. You must, therefore, come to seminars armed with your notes, having

already thought about what you’re going to say. You may change your mind — or you

may convince others of your point of view.

Seminars are centred on group work and adopt a problem based learning

approach, that is, students are required to find the answers to key questions

that the course co-ordinator will help you formulate. The manner in which these

sessions will be run will be discussed in detail in the first seminar.

Twenty percent of your overall mark is based on seminar participation of one sort or

another. You should take this into consideration when calculating your workload.

Students must attend on a regular basis in order to complete the requirements of the

course. Absences from tutorials should be accompanied by evidence of illness or

misadventure. A minimum of 80% tutorial attendance is expected. Students who

miss more than three tutorials will be required to submit an extra essay. A

student whose attendance record in less than 50% is considered not to have

fulfilled the course requirements.

You are expected to come to seminars prepared to discuss the issues involved. The

mark for seminar participation is based upon the student’s ability to take part

in class discussions. No mark is given for class attendance.

In the following pages you will find that each seminar is centred around a theme. A

list of readings is provided that will help you find the answers to those themes. You

will find the books and articles in the short loans section of the Auchmuty Library. You

are encouraged to read something that is of interest to you and to come to class

prepared to share your findings with the other students.

How much reading should you do?

A lot. It is vital that you should read a variety of works, otherwise you will get a onesided view of the topic. You must be able to join in a discussion on the questions

given, and you should do enough reading to give you the necessary information and

confidence.

Method of Assessment

The assessment has been divided along the following lines:

Research essay (4000 words)

40%

Minor essay (2000 words)

20%

Trial (equivalent of 2000 words)

20%

Group participation

20%

Total

100%

School of Humanities and Social Science

2

1.

All students are required to submit a minor essay based on one of the

Seminar topics, one week after that particular seminar.

2.

All students are required to submit a major essay chosen from the list at the

back of the course guide.

3.

All students are required to take part in the Trial.

The Trial

At the end of the course we will put the French Revolution and Napoleon on trial. The

purpose of the re-enactment is to deepen our understanding of the issues involved.

Each class member will be assigned a role as an historical personage involved in

these events whose reactions to the debate would typify those of an important group

at the time.

Each class member will research his/her role and be prepared to perform “in

character” during the re-enactment.

Plagiarism

University policy prohibits students plagiarising any material under any

circumstances. A student plagiarises if he or she presents the thoughts or works of

another as one's own. Without limiting the generality of this definition, it may include:

·

copying or paraphrasing material from any source without due

acknowledgment;

·

using another's ideas without due acknowledgment;

·

working with others without permission and presenting the resulting work as

though it was completed independently.

Plagiarism is not only related to written works, but also to material such as data,

images, music, formulae, websites and computer programs.

Aiding another student to plagiarise is also a violation of the Plagiarism Policy and

may invoke a penalty.

For further information on the University policy on plagiarism, please refer to the

Policy on Student Academic Integrity at the following link http://www.newcastle.edu.au/policy/academic/general/academic_integrity_polic

y_new.pdf

The University has established a software plagiarism detection system called

Turnitin. When you submit assessment items please be aware that for the purpose of

assessing any assessment item the University may ·

Reproduce this assessment item and provide a copy to another member of

the University; and/or

·

Communicate a copy of this assessment item to a plagiarism checking

service (which may then retain a copy of the item on its database for the

purpose of future plagiarism checking).

·

Submit the assessment item to other forms of plagiarism checking

School of Humanities and Social Science

3

Written Assessment Items

Students may be required to provide written assessment items in electronic form as

well as hard copy.

Extension of Time for Assessment Items, Deferred Assessment and Special

Consideration for Assessment Items or Formal Written Examinations

Students are required to submit assessment items by the due date, as advised in the

Course Outline, unless the Course Coordinator approves an extension of time for

submission of the item. University policy is that an assessment item submitted after

the due date, without an approved extension, will be penalised.

Any student:

1. who is applying for an extension of time for submission of an assessment item on

the basis of medical, compassionate, hardship/trauma or unavoidable commitment;

or

2. whose attendance at or performance in an assessment item or formal written

examination has been or will be affected by medical, compassionate,

hardship/trauma or unavoidable commitment;

must report the circumstances, with supporting documentation, to the appropriate

officer on the prescribed form.

Please go to the Policy and the on-line form for further information, particularly for

information on the options available to you, at:

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/policy/academic/adm_prog/adverse_circumstanc

es.pdf

Students should be aware of the following important deadlines:

·

Requests for Special Consideration must be lodged no later than 3 working

days after the date of submission or examination.

·

Requests for Extensions of Time on Assessment Items must be lodged

no later than the due date of the item.

·

Requests for Rescheduling Exams must be lodged no later than 5 working

days before the date of the examination.

Your application may not be accepted if it is received after the deadline. Students

who are unable to meet the above deadlines due to extenuating circumstances

should speak to their Program Officer in the first instance.

Changing your Enrolment

The last dates to withdraw without financial or academic penalty (called the HECS

Census Dates) are:

For semester 1 courses: 31 March 2007

For semester 2 courses: 31 August 2007

For Trimester 1 courses: 17 February 2007

For Trimester 2 courses: 9 June 2007

For Trimester 3 courses: 22 September 2007.

School of Humanities and Social Science

4

Students may withdraw from a course without academic penalty on or before the last

day of semester and prior to the commencement of the formal exam period. Any

withdrawal from a course after the last day of semester will result in a fail grade.

Students cannot enrol in a new course after the second week of semester/trimester,

except under exceptional circumstances. Any application to add a course after the

second week of semester/trimester must be on the appropriate form, and should be

discussed with the Student Enquiry Centre.

To change your enrolment online, please refer to

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/study/enrolment/changingenrolment.html

Contact Details

Faculty Student Service Offices

The Faculty of Education and Arts

Room: Level 3, Shortland Union, Callaghan

Phone: 02 4921 5000

Ourimbah Focus

Room: AB1.01 (Administration Building)

Phone: 02 4348 4030

The Dean of Students

Dr Michael Hannaford

Phone: 02 4921 5806

Fax: 02 4921 7151

resolutionprecinct@newcastle.edu.au

Deputy Dean of Students (Ourimbah)

Dr Bill Gladstone

Phone: 02 4348 4123

Fax: 02 4348 4145

Various services are offered by the University Student Support Unit:

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/study/studentsupport/index.html

Alteration of this Course Outline

No change to this course outline will be permitted after the end of the second week of

the term except in exceptional circumstances and with Head of School approval.

Students will be notified in advance of any approved changes to this outline.

Web Address for Rules Governing Undergraduate Academic Awards

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/policy/academic/cw_ugrad/awards.pdf

Web Address for Rules Governing Postgraduate Academic Awards

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/policy/academic/cw_pgrad/cppcrule.pdf

Web Address for Rules Governing Professional Doctorate Awards

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/policy/academic/cw_pgrad/prof_doct.pdf

School of Humanities and Social Science

5

STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY OR CHRONIC ILLNESS

The University is committed to providing a range of support services for students with

a disability or chronic illness.

If you have a disability or chronic illness which you feel may impact on your studies,

please feel free to discuss your support needs with your lecturer or course

coordinator.

Disability Support may also be provided by the Student Support Service (Disability).

Students must be registered to receive this type of support. To register please

contact the Disability Liaison Officer on 02 4921 5766, or via email at: studentdisability@newcastle.edu.au

As some forms of support can take a few weeks to implement it is extremely

important that you discuss your needs with your lecturer, course coordinator or

Student Support Service staff at the beginning of each semester.

For more information related to confidentiality and documentation please visit the

Student Support Service (Disability) website at:

www.newcastle.edu.au/services/disability

------------------------------------------------ End of CTS Entry --------------------------------------Written Assignment Presentation and Submission Details

Students are required to submit assessment items by the due date. Late

assignments will be subject to the penalties described below.

Hard copy submission:

Type your assignments: All work must be typewritten in 12 point black font. Leave a

wide margin for marker’s comments, use double spacing, and include page numbers.

Word length: The word limit of all assessment items should be strictly followed –

10% above or below is acceptable, otherwise penalties may apply.

Proof read your work because spelling, grammatical and referencing mistakes will be

penalised.

Staple the pages of your assignment together (do not use pins or paper clips).

University Assessment Item Coversheet: All assignments must be submitted with

the University coversheet available at: http://www.newcastle.edu.au/study/forms/

By arrangement with the relevant lecturer, assignments may be submitted at any

Student Hub located at:

o

Level 3, Shortland Union, Callaghan

o

Level 2, Student Services Centre, Callaghan

o

Ground Floor, University House, City

o

Ground Floor, Administration Building, Ourimbah

Date-stamping assignments: All students must date-stamp their own assignments

using the machine provided at each Student Hub. If mailing an assignment, this should

be address to the relevant School. Mailed assignments are accepted from the date

posted, confirmed by a Post Office date-stamp; they are also date-stamped upon receipt

by Schools.

School of Humanities and Social Science

6

Do not fax or email assignments: Only hard copies of assignments will be considered

for assessment. Inability to physically submit a hard copy of an assignment by the

deadline due to other commitments or distance from campus is an unacceptable excuse.

Keep a copy of all assignments: It is the student’s responsibility to produce a copy of

their work if the assignment goes astray after submission. Students are advised to keep

updated back-ups in electronic and hard copy formats.

Penalties for Late Assignments

Assignments submitted after the due date, without an approved extension of time will

be penalised by the reduction of 5% of the possible maximum mark for the

assessment item for each day or part day that the item is late. Weekends count as

one day in determining the penalty. Assessment items submitted more than ten

days after the due date will be awarded zero marks.

Special Circumstances

Students wishing to apply for Special Circumstances or Extension of Time should

apply online @ http://www.newcastle.edu.au/policylibrary/000641.html

No Assignment Re-submission

Students who have failed an assignment are not permitted to revise and resubmit it in

this course. However, students are always welcome to contact their Tutor, Lecturer

or Course Coordinator to make a consultation time to receive individual feedback on

their assignments.

Remarks

Students can request to have their work re-marked by the Course Coordinator or

Discipline Convenor (or their delegate); three outcomes are possible: the same grade,

a lower grade, or a higher grade being awarded. Students may also appeal against

their final result for a course. Please consult the University policy at:

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/study/forms/

Return of Assignments

Students can collect assignments from a nominated Student Hub during office

hours. Students will be informed during class which Hub to go to and the earliest date

that assignments will be available for collection. Students must present their student

identification card to collect their assignment.

Preferred Referencing Style

In this course, it is recommended that you use the Chicago style referencing system

for sources used in assignments. Inadequate or incorrect reference to the work of

others may be viewed as plagiarism and result in reduced marks or failure.

Refer to the instructions at the back of this course guide.

Online Tutorial Registration:

Students are required to enrol in the Lecture and a specific Tutorial time for this

course via the Online Registration system:

http://studinfo1.newcastle.edu.au/rego/stud_choose_login.cfm

Registrations close at the end of week 2 of semester.

Studentmail and Blackboard: www.blackboard.newcastle.edu.au/

This course uses Blackboard and studentmail to contact students, so you are

advised to keep your email accounts within the quota to ensure you receive advised

messages. To receive an expedited response to queries, post questions on the

School of Humanities and Social Science

7

Blackboard discussion forum if there is one, or if emailing staff directly use the course

code in the subject line of your email. Students are advised to check their studentmail

and the course Blackboard site on a weekly basis.

Student Representatives

Student Representatives are a major channel of communication between students

and the School. Contact details of Student Representatives can be found on School

websites.

Student Communication

Students should discuss any course related matters with their Tutor, Lecturer, or

Course Coordinator in the first instance and then the relevant Discipline or Program

Convenor. If this proves unsatisfactory, they should then contact the Head of School

if required. Contact details can be found on the School website.

Essential Online Information for Students

Information on Class and Exam Timetables, Tutorial Online Registration, Learning

Support, Campus Maps, Careers information, Counselling, the Health Service and a

range of free Student Support Services can be found at:

http://www.newcastle.edu.au/currentstudents/index.html

Grading guide

49% or less

Fail

(FF)

50% to 64%

Pass

(P)

65% to 74%

Credit

(C)

75% to 84%

Distinction

(D)

85% upwards

High

Distinction

(HD)

An unacceptable effort, including non-completion. The student has not

understood the basic principles of the subject matter and/or has been unable to

express their understanding in a comprehensible way. Deficient in terms of

answering the question, research, referencing and correct presentation

(spelling, grammar etc). May include extensive plagiarism.

The work demonstrates a reasonable attempt to answer the question,

shows some grasp of the basic principles of the subject matter and a basic

knowledge of the required readings, is comprehensible, accurate and

adequately referenced.

The work demonstrates a clear understanding of the question, a capacity to

integrate research into the discussion, and a critical appreciation of a

range of different theoretical perspectives. A deficiency in any of the

above may be compensated by evidence of independent thought.

The work is coherent and accurate.

Evidence of substantial additional reading and/or research, and evidence of

the ability to generalise from the theoretical content to develop an

argument in an informed and original manner. The work is well

organised, clearly expressed and shows a capacity for critical analysis.

All of the above, plus a thorough understanding of the subject matter based on

substantial additional reading and/or research. The work shows a high level

of independent thought, presents informed and insightful discussion of

the topic, particularly the theoretical issues involved, and demonstrates a

well-developed capacity for critical analysis.

School of Humanities and Social Science

8

OVERVIEW OF SEMINAR

AND LECTURE TIMETABLE

Date

Seminars

Lectures

Week 1

No seminars this week

Introductory Lecture

Week 2

Introductory seminar

A. Ancien Régime France

B. Ancien Régime France

Week 3

Ancien Régime France

A. The Decline of the Monarchy

B. The Calling of the Estates-General

Week 4

The Nobilty, the Parlements A. The Urban and Rural Revolt

and the Pre-revolution

B. The End of the Moderate Revolution

Rural and Urban Revolt

A. The Rise of the Republican Movement

Week 5

B. The War Against Europe

Week 6

Religion and the Church

Week 7

Radical Politics and the A. The Fall of the Girondins

People

B. The Dominance of the Sans-culottes

Mid-Semester Recess

Week 8

The Terror

A. The Fall of the Monarchy

B. The Struggle for Power

Friday, 6 April to Friday, 20 April

A. The Dictatorship of the Committee of

Public Safety

B. The Fall of Robespierre and the End

of the Terror

Week 9

The Rise of Napoleon

Week 10

Napoleonic France: Order A. The Fabrication of Power

and Stability

B. Founding an Empire: The Conquest of

Major Essay Due

Europe

Week 11

Napoleon’s

Europe

Week 12

The Fall of Napoleon

Trial preparation

Trial preparation

Week 13

Week 14

Conquest

A. The Bourgeois Republic

B. Brumaire: The Acquisition of Power

of A. The Peninsular War

B. The Invasion of Russia

A. Napoleon’s Fall from Power

B. The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism

A. The Impact of the Revolution and

Napoleon on France and Europe

The French Revolution

and Napoleon on Trial

School of Humanities and Social Science

9

READING LIST

You are expected to read extensively and to become acquainted with the works of

the major historians and with the major historiographical debates. The list below is

meant to serve as a guideline; there are fuller reading lists attached to the seminar

topics and, of course, you should take the initiative to delve into the library and read

whatever you find of interest there. All of the books and articles mentioned in the

seminar reading lists are held on short loan or on three-day loan.

Textbooks

are available for purchase at the University Bookshop.

D. M. G. Sutherland, The French Revolution and Empire: The Quest for a Civic

Order. London: Blackwell, 2003.

François Furet, The French Revolution, 1770-1814. London: Blackwell, 1996.

Peter McPhee, The French Revolution, 1789-1799. Oxford: OUP, 2002.

William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Oxford: OUP, 1989.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution.

London: Macmillan, 1994.

Highly recommended reading

T. C. W. Blanning. The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787-1802. London: Edward

Arnold, 1996.

Malcom Crook, Napoleon comes to power: Democracy and dictatorship in

revolutionary France, 1795-1804. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1998.

Jean Paul Kauffmann, The Black Room at Longwood: Napoleon’s Exile on St.

Helena. 1998.

Hugh Gough, The Terror in the French Revolution. London: Macmillan, 1998.

Peter McPhee, Living the French Revolution, 1789-1799. London: Palgrave

Macmillan, 2007.

Simon Schama, Citizens. A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York:

Vintage, 1989.

Other recommended texts

On the French Revolution

David Andress, French Society in Revolution, 1789-1799. Manchester: Manchester

University Press, 1999.

T. C. W. Blanning, The French Revolution: Aristocrats versus Bourgeois. Oxford:

OUP, 1987.

William Doyle, The French Revolution. Oxford: OUP, 2001.

William Doyle, Origins of the French Revolution. Oxford: OUP, 1988.

Alan Forrest, The French Revolution. Oxford: Blackwell, 1995.

Peter Jones (ed.), The French Revolution in Social and Political Perspective.

London: Arnold, 1996.

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution. New Jersey: Prentice

Hall, 1998.

Michel Vovelle, The Fall of the French Monarchy. Cambridge: CUP, 1984.

School of Humanities and Social Science

10

On Napoleon and the Empire

David A. Bell, The First Total War: Napoleon's Europe and the Birth of Warfare

as We Know It. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2007.

Michael Broers, Europe under Napoleon. London: Edward Arnold, 1996.

Philip Dwyer (ed.), Napoleon and Europe. London: Addison Wesley Longman,

2001.

Philip Dwyer and Alan Forrest (eds), Napoleon and His Empire: Europe, 18041814. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Geoffrey Ellis, Napoleon. London: Addison Wesley Longman, 1996.

Geoffrey Ellis, The Napoleonic Empire. London: Macmillan, 1991,

Charles Esdaile, The Wars of Napoleon. London: Addison Wesley Longman, 1995.

Charles Esdaile, French Wars, 1792-1815. London: Routledge, 2001.

David Gates, The Napoleonic Wars, 1803-1815. London: Arnold, 1997.

Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux (eds), Napoleon and His Times: Selected

Interpretations. Malabar: Krieger, 1989.

Laven, David and Riall, Lucy (eds), Napoleon’s Legacy: Problems of Government

in Restoration Europe. Berg: Oxford, 2000.

Biographies

For the Revolution

Philip Dwyer, Talleyrand. London: Longman, 2002.

Antonia Fraser, Marie Antoinette: The Journey. New York: Anchor Books, 2002.

N. Hampson, Danton. London: Duckworth, 1978.

N. Hampson, Saint-Just. Oxford: Blackwell, 1991.

John Hardman, Louis XVI. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1993.

John Hardman, Robespierre. London: Longman, 1999.

John Hardman, Louis XVI: The Silent King. London: Arnold, 2000.

Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France. New York: Farrar,

Straus and Giroux, 2000.

On Napoleon

Philip Dwyer, Napoleon Bonaparte: The Path to Power, 1769-1799. London:

Bloomsbury (June 2007).

Steven Englund, Napoleon: A Political Life. New York: Scribner, 2004.

George Lefebvre, Napoleon. London: Routledge, 1969.

Felix Markham, Napoleon. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1963.

Felix Markham, Napoleon and the Awakening of Europe. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1958.

Alan Schom, Napoleon Bonaparte. London: Harper Collins, 1998.

J. M. Thompson, Napoleon Bonaparte: His Rise and Fall. Oxford: Blackwell, 1952.

Primary Sources

Jack R. Censer and Lynn Hunt. Liberty, equality, fraternity: exploring the French Revolution.

University Park, Pa., Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001.

School of Humanities and Social Science

11

Richard Cobb and Colin Jones (eds), The French Revolution: voices from a momentous epoch, 17891795. London: Simon & Schuster, 1988.

Philip Dwyer and Peter McPhee (eds), The French Revolution and Napoleon: A Sourcebook. London:

Routledge, 2002.

J. Christopher Herold (ed.), The mind of Napoleon: a selection from his written and spoken words.

New York: Columbia University Press, 1961.

Jocelyn Hunt, The French Revolution (London ; New York, NY: Routledge, 1998).

J. Gilchrist and W. Murray, eds., The Press in the French Revolution; a selection of documents taken

from the press of the Revolution for the years 1789-1794 (London, 1971).

J. H. Stewart, A Documentary Survey of the French Revolution (New York, 1951).

J. M. Thompson (ed.), Napoleon’s Letters. London: Dent, 1954.

M. Walzer, Regicide and Revolution: speeches at the trial of Louis XVI (London, 1974).

Donald Wright, The French Revolution: introductory documents (St. Lucia, Queensland 1975).

Recommended Web Sites (containing documentary sources)

Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. Exploring the French Revolution — http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/

NapoleonSeries.Org — http://www.napoleonseries.com/index.cfm

Reference guides

There are a number of good dictionaries that you should consult whenever you are unsure about an

individual or an event that you are reading or researching.

David Chandler, Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. New York: Macmillan, 1979.

Owen Connelly, Harold T. Parker, et al. Historical dictionary of Napoleonic France, 1799-1815.

Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Clive Emsley, The Longman Companion to Napoleonic Europe. London: Addison Wesley Longman,

1993.

Francois Furet, and Mona Ozouf (eds.), A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Cambridge,

Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1989.

Colin Jones, The Longman Companion to the French Revolution. London: Longman, 1990.

S. Scott and B. Rothaus (eds), Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution. 2 vols. Westport,

Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1985.

Other useful general histories

George Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967.

Gwynne Lewis, The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate. London: Routledge, 1993.

Pieter Geyl, Napoleon: For and Against. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1982.

Furet, F. and Richet, D. The French Revolution. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1970.

George Rudé, The French Revolution. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1988.

Paul W. Schroeder, The Transformation of European Politics, 1763-1848. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

H. M. Scott, The Birth of a Great Power System, 1740-1815. Harlow: Pearson/Longman,

2006.

Stuart Woolf, Napoleon’s Integration of Europe. London: Routledge, 1991.

D. G. Wright, Napoleon and Europe. London: Addison Wesley Longman, 1984.

School of Humanities and Social Science

12

Seminar Programme

Week 1

19 February

There is an introductory lecture this week.

There are no seminars this week

School of Humanities and Social Science

13

Week 2

26 February

Introductory seminar this week

The first seminar will mainly be concerned with explaining what the course is about

and answering any questions you may have. This is the first time that you will meet

your tutor and the other people in the class with whom you will be working for the

next three months. So, we will take a little time out to find out what the tutor expects

of you, what the course is about and, just as importantly, what you expect from the

tutor and the course.

School of Humanities and Social Science

14

Week 3

5 March

The Ancien Régime:

Government and Society

The problem

An analysis of pre-revolutionary French society is necessary if we are to understand how the

Revolution came about and if we are to appreciate the extent of the changes which occurred after 1789.

This seminar will concentrate on the social and administrative structures of France under the Ancien

Régime and will look at some of the problems that it was faced with. By the end of your readings you

should be familiar with the monarchy and the manner in which the king ruled; the nature and structure

of French society, especially the parts played in it by the nobility and the bourgeoisie; and whether

France was any more or less stagnant than other European societies.

Seminar themes

Why was the French monarchy unable to impose badly needed reforms during the years leading up to

1789?

Do ideas make revolutions?

The Government

Peter Campbell, The Ancien Regime in France (Oxford, New York, 1988).

W. Doyle, The Ancien Regime (Basingstoke, Hampshire, 1986).

W. Doyle, Origins of the French Revolution (Oxford, New York, 1988), chs. 6 and 7.

W. Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (Oxford, 1989), ch. 1.

François Furet & Mona Ozouf, A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (Cambridge, Mass.,

1989), esp. the articles on Ancien Régime, Louis XVI, Marie-Antoinette, Necker, and the Constitution.

John Hardman, Louis XVI (New Haven and London, 1993).

John Hardman, French Politics, 1774-89 (London, 1995), esp. chs. 9 and 10 on the king and queen, and

11 and 12 on the monarchy and politics.

Peter Jones, The Peasantry in the French Revolution (Cambridge, 1988), ch. 1.

P. M. Jones, Reform and Revolution in France: The Politics of Transition, 1774-91 (Cambridge, 1995),

ch. 1.

Peter McPhee, A Social History of France, 1780-1880 (London, 1992), ch. 1.

Annie Moulin, Peasantry and Society in France since 1789 (Cambridge, 1991), pp. 4-23.

David Parker, The Making of French Absolutism (London, 1983), pp. 118-151.

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution (New Jersey, 1998), ch. 1.

Albert Soboul, The French Revolution, 1787-1799: from the storming of the Bastille to Napoleon

(London, 1974), ch. 2.

Michel Vovelle, The Fall of the French Monarchy (Cambridge, 1984), pp. 24-37.

Society and the Economy

David Andress, French Society in Revolution (Manchester, 1999), ch. 1.

School of Humanities and Social Science

15

P. M. Jones, Reform and Revolution in France: The Politics of Transition, 1774-91 (Cambridge, 1995),

ch. 2.

G. Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution (Princeton, N. J., 1967).

Peter McPhee, The French Revolution, 1789-1799 (Oxford, 2002), ch. 1.

The Enlightenment

Keith Baker, Inventing the French Revolution: essays on French political culture in the eighteenth

century (Cambridge, 1990), pp. 12-27.

Keith Baker, ed., The French Revolution and the Creation of Modern Political Culture, vol. 1 (Oxford,

1987), esp. the articles by Doyle and Baker.

Keith Baker, “Enlightenment and Revolution in France: Old Problems, Renewed Approaches,” Journal

of Modern History 53 (1981): 281-303.

T. C. W. Blanning, The French Revolution: aristocrats versus bourgeois? (Houndmills, Basingstoke,

Hampshire, 1987), pp. 18-32.

Maurice Cranston, “Ideas and Ideologies,” History Today 5 (1989): 10-14.

Roger Chartier, “Do Books Make Revolutions?,” in The French Revolution in social and political

perspective (London, 1996), ed. Peter Jones, pp. 166-188.

Robert Darnton, “The Facts of Literary Life in Eighteenth Century France,” in The French Revolution

and the Creation of Modern Political Culture, ed. Keith Baker, vol. 1, pp. 261-291.

R. Darnton, The Literary Underground of the Old Régime (Cambridge, 1982).

François Furet & Ozouf, A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1989), esp.

contributions on the Ancien Regime, Enlightenment, Montesquieu, Rousseau, and Sovereignty.

N. Hampson, Will and Circumstance. Montesquieu. Rousseau and the French Revolution (London,

1983).

Margaret Jacob, “The Enlightenment Redefined,” in The French Revolution in social and political

perspective (London, 1996), ed. Peter Jones, pp. 203-13.

G. Lewis, The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate (London, 1993), ch. 1.

Dorinda Outram, The Enlightenment (Cambridge, New York, 1995), ch. 2.

William H. Sewell Jr., “Ideologies and Social Revolutions: Reflections on the French Case,” Journal of

Modern History 57 (1985): 57-85.

Timothy Tackett, Becoming a Revolutionary: the deputies of the French National Assembly and the

emergence of a revolutionary culture (Princeton, N. J., 1995), ch. 2.

Michel Vovelle, The Fall of the French monarchy, 1787-1792 (Cambridge, 1984), pp. 59-72.

School of Humanities and Social Science

16

Week 4

12 March

The Nobility, the Parlements and the Pre-Revolution

The problem

Supreme paradox, it was the privileged classes that instituted the chain of events leading to the

Revolution which saw their downfall. This at least was the commonly accepted interpretation amongst

Marxist historians up until the 1960s. But is this an adequate explanation? Certainly the members of the

Parlements, the courts of justice, were the first to speak publicly of fundamental rights and liberties and

it was they who clamoured for the convocation of the Estates-General when faced with what they

considered to be ‘ministerial despotism.’ But did they for all that cause the Revolution?

Seminar themes

Was the conflict between the nobility and the bourgeoisie before 1789 a class conflict?

How responsible were the personal failings of Marie-Antoinette and Louis XVI for the outbreak of revolution in 1789?

To what extent do the cahiers suggest that a revolution had occurred in the minds of the French people

before 1789?

The Nobility and the Parlements

David Andress, French Society in Revolution (Manchester, 1999), ch. 2.

Nigel Aston, The End of an Elite: The French Bishops and the Coming of the Revolution, 1786-90

(Oxford, 1992), ch. 1.

William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (Oxford, 1989), ch. 3.

William Doyle, The Origins of the French Revolution (Oxford, 1988), pp. 98-114.

William Doyle “Was there an aristocratic reaction in pre-revolutionary France,” Past and Present, 57

(1972), pp. 97-122.

Alan Forrest, The French Revolution (Oxford, 1995), pp. 13-39.

P. M. Jones, Reform and Revolution in France: The Politics of Transition, 1774-91 (Cambridge, 1995),

ch. 5.

George Lefebvre, The French Revolution from its Origins to 1793 (London, 1964), vol. 1, pp. 43-49

and 97-130.

Peter McPhee, The French Revolution, 1789-1799 (Oxford, 2002), ch. 2.

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution (New Jersey, 1998), pp. 21-6.

D. M. G. Sutherland, France 1789-1815: Revolution and Counter-Revolution (London, 1985), chs. 1

and 2.

Michel Vovelle, The Fall of the French Monarchy (Cambridge, 1984), pp. 73-98.

School of Humanities and Social Science

17

The Bourgeoisie

Robert Darnton, “A bourgeois puts his world in order: the city as text,” in The Great Cat Massacre and

Other Episodes in French Cultural History, pp. 105-140.

C. Jones, “Bourgeois Revolution revivified: 1789 and social change,” in Rewriting the French

Revolution, ed. C. Lucas (1991), pp. 69-118.

Colin Lucas, “Nobles, bourgeois and the origins of the French Revolution,” Past and Present 60

(1973): 84-126.

S. Scott & B. Rothaus, eds., Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution (Westport, Conn., 1984),

article on the “Bourgeoisie”.

Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette

Rory Browne, “The Diamond Necklace affair revisited,” Renaissance and Modern Studies 33 (1989):

21-39.

Terry Castle, “The Marie Antoinette Obessession,” in The Apparitional Lesbian (New York, 1993), pp.

107-149.

Antonia Fraser, Marie Antoinette (London, 2002).

Evelyne Lever, Marie Antoinette: The Last Queen of France (New York, 2001).

John Hardman, French politics, 1774-1789: from the accession of Louis XVI to the

fall of the Bastille (London, 1995), chs. 9 and 10.

John Hardman, Louis XVI (New Haven, Conn., 1993).

John Hardman, Louis XVI: the silent king (London, 2000).

Lynn Hunt, “The Many Bodies of Marie-Antoinette: Political Pornography and the Problem of the

Feminine in the French Revolution,” in id., Eroticism and the Body Politic (Baltimore, 1991), pp. 108130.

Sarah Maza, “The Diamond Necklace Affair Revisited (1785-1786): The Case of the Missing Queen,”

in Eroticism and the Body Politic, ed. Lynn Hunt (Baltimore, 1991), pp. 63-89.

Sarah Maza, Private Lives and Public Affairs: The Causes Célèbres of pre-Revolutionary France

(Berkeley, 1993), pp. 167-211.

School of Humanities and Social Science

18

Week 5

19 March

Urban and Rural France in Revolt:

Peasant and Worker Mentality in 1789

The problem

There is no doubt that the peasant revolts during summer of 1789 helped bring about the end of the

Ancien Régime but there is complete disagreement about why these revolts took place. According to the

French Marxist historian, Albert Soboul, the peasantry revolted in order to free themselves from a

repressive feudal society. The revisionist historian, François Furet, on the other hand, argues that this

interpretation is greatly exaggerated and asserts that the aristocracy served as a scapegoat for the

peasantry. Which interpretation is right, or do both contain an element of historical truth? How does

one explain the outbreak of peasant violence in 1789? The “popular revolt” also spread to Paris. Was

the storming of the Bastille part of a national uprising or simply a Parisian riot?

Seminar theme

Why did the Revolution become a popular movement by the summer of 1789?

The Peasantry

David Andress, French Society in Revolution (Manchester, 1999), ch. 3.

William Doyle, The Origins of the French Revolution (Oxford, 1988), ch. 12.

François Furet, Interpreting the French Revolution (Cambridge, 1981), pp. 92-100.

F. Furet and D. Richet, The French Revolution (London, 1970), pp. 82-84.

Peter Jones, The Peasantry in the French Revolution (Cambridge, 1988), pp. 30-34 and 60-85.

Peter Jones, “The Peasant revolt?,” History Today 5 (1989): 15-19.

Georges Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution (Princeton, N. J., 1967), pp. 127-130.

John Markoff, “Peasant Grievances and Peasant Insurrection: France in 1789,” Journal of Modern

History 62 (1990): 445-476.

J. Markoff, “Violence, emancipation and democracy: the countryside and the French Revolution,”

American Historical Review 100 (1995): 360-86.

Peter McPhee, The French Revolution, 1789-1799 (Oxford, 2002), ch. 3.

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution (New Jersey, 1998), pp. 26-34.

Albert Soboul, “An Attack on Feudalism,” in The French Revolution. Conflicting Interpretations

(Malabar, Fl., 1989), eds. F. A. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 82-93.

D. M. G. Sutherland, France 1789-1815: Revolution and Counter-Revolution

(London, 1985), pp. 49-52, 68-80.

Arthur Young, Travels in France in the Years 1787, 1788 and 1789 (Cambridge, 1929).

The Palais Royal

Jules Michelet, History of the French Revolution (Chicago, 1967).

Arthur Young, Travels in France in the Years 1787, 1788 and 1789 (Cambridge, 1929).

Robert Isherwood, Farce and Fantasy. Popular Entertainment in Eighteenth-Century Paris (New

York, 1986), ch. 8.

School of Humanities and Social Science

19

D. M. McMahon, “The Birthplace of the Revolution: Politics and Political Community in the PalaisRoyal of Louis-Philippe d’Orléans, 1781-1789,” French History, 10 (1996): 1-29.

The Storming of the Bastille

R. Cobb, “The beginning of the Revolutionary crisis in Paris,” in A Second Identity, ed. R. Cobb

(London, 1969), pp. 145-58.

W. Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (Oxford, 1989), chs. 4, 5

Jacques Godechot, “The Uprising of July 14: Who Participated?” in The French Revolution.

Conflicting Interpretations (Malabar, Fl., 1989), eds. F. A. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 66-79.

G. Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution (Princeton, N. J., 1967), pp. 110-122.

Hans-Jurgen Lusebrink and Rolf Reichardt, The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and

Freedom (Durham, N. C., 1998), pp. 38-47.

S. Schama, Citizens: a chronicle of the French Revolution (London, 1989), pp. 369-469.

School of Humanities and Social Science

20

Week 6

26 March

The Catholic Church

and the Civil Constitution of the Clergy

The problem

Just as the revolutionaries attempted to transform the State’s administrative and financial apparatus, so

too did they attempt to transform the Church into a temporal institution. The Revolution’s answer to the

Church was the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, introduced in June 1790. This was the most

controversial of all the reforms introduced by the Constituent Assembly. The Revolution’s treatment of

the Church forced many of its members into the counter-revolution and linked republicanism with anticlericalism for more than a century to come. Where did the Assembly go wrong? Were the deputies

motivated by practical or ideological reasons?

Seminar theme

Was a clash between the Church and the Revolution inevitable?

The Church

N. Aston, The End of an Elite: The French Bishops and the Coming of the Revolution, 1786-1790

(Oxford, 1992), chs. 8-12.

William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (Oxford, 1989), pp. 139-46.

Philip Dwyer, Talleyrand (London, 2002), ch. 2.

F. Furet & M. Ozouf, Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1989), article

on Civil Constitution of Clergy.

Ralph Gibson, A Social History of French Catholicism, 1789-1914 (New York, 1989), chs. 1 and 2.

André Latreille, “Tragic Errors,’ in The French Revolution. Conflicting Interpretations (Malabar, Fl.,

1989), eds. F. A.. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 120-129.

George Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution (Princeton, N. J., 1967), pp. 39-41 and 166171.

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution (New Jersey, 1998), ch. 3.

D. M. G. Sutherland, France, 1789-1815: Revolution and Counter-Revolution (London, 1985), pp. 9399.

T. Tackett, Religion, Revolution and Regional Culture: the Ecclesiastical Oath of 1791: the

ecclesiastical oath of 1791 (Princeton, N. J., 1986), ch. 1.

M. Vovelle, The Revolution against the Church: from reason to the Supreme Being (Columbus, 1991),

pp. 12-24.

School of Humanities and Social Science

21

Week 7

2 April

Blood and Bread:

Radical Politics and the People

The problem

The year 1793 was the apogee of what some historians have called ‘The Great Revolution.’ It was the

year when the sans-culottes came into their own, the year when ‘St. Pike’ was venerated. It was also the

year when the Revolution had its back to the wall and when it looked as though things would go badly.

It is almost axiomatic to say that in such circumstances politicians become radical and politics becomes

extreme. Although the popular movement was incredibly violent and full of contradictions, it

nevertheless represented the social and political aspirations of the people, aspirations that inevitably

came into conflict with those of the bourgeoisie. The revolt of the people is one point on which

historians will not only diverge on ideological grounds but on relatively simple questions like whether it

was a good or bad thing, whether it was avoidable or inevitable, indeed whether one should have even

tried to avoid it.

Seminar theme

Who were the sans-culottes and what kind of Republic were they struggling for?

Paris and the Sans-culottes

David Andress, French Society in Revolution (Manchester, 1999), ch. 5.

Richard Cobb, “A Critique,” in The French Revolution. Conflicting Interpretations (Malabar, Fl.,

1989), eds. F. A. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 259-69.

Richard Cobb, “The revolutionary mentality in France,” History 42 (1957): 181-196.

Richard Cobb, “The People and the French Revolution,” Past and Present 15 (1959): 60-72.

Richard Cobb, The Police and the People: French popular protest, 1789-1820 (Oxford, 1970), pp. 172325.

F. Furet, C. Mazauric and L. Bergeron, “The Sans-Culottes and the French Revolution,” in New

Perspectives on the French Revolution (New York, 1965), ed. J. Kaplow, pp. 226-253.

Louis R. Gottschalk, Jean-Paul Marat: a study in radicalism (Chicago, 1967), ch. 4.

G. Lewis, The French Revolution: Rethinking the Debate (London, 1993), pp. 37-49.

C. Lucas, “The Crowd and Politics,” in The French Revolution and the Creation of Modern Political

Culture (Oxford, 1989), ed. C. Lucas, vol. 2, pp. 259-285.

C. Lucas, “The Crowd and Politics between Ancien Régime and Revolution in France,” Journal of

Modern History 60 (1988): 421-457.

C. Lucas, “Talking about Urban Popular Violence in 1789,” in Reshaping France: town, country, and

region during the French Revolution (New York, 1991), eds. Alan Forrest and Peter Jones, pp. 122136.

C. Lucas, “Revolutionary Violence, the People and the Terror,” in The French Revolution and the

Creation of Modern Political Culture (Oxford, 1989), ed. Keith Baker, vol. 4, pp. 57-79.

Lefebvre, G., “Revolutionary Crowds,” in New Perspectives on the French Revolution (New York,

1965), ed. J. Kaplow, pp. 183-190.

George Rudé, “The Rioters,” in The French Revolution. Conflicting Interpretations (Malabar, Fl.,

1989), eds. F. A. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 230-41.

School of Humanities and Social Science

22

George Rudé, The Crowd in the French Revolution (Oxford, 1959), pp. 1-45, 178-l91.

Simon Schama, Citizens: a chronicle of the French Revolution (London, 1989), pp. 710-714, 719-722,

731-742.

Albert Soboul, The Parisian Sans-culottes and the French Revolution (Oxford, 1964).

Albert Soboul, “The Sans-Culottes,” in The French Revolution. Conflicting Interpretations (Malabar,

Fl., 1989), eds. F. A. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 242-58.

Michael Sonenscher, “Artisans, sans-culottes and the French Revolution,” in Reshaping France: town,

country, and region during the French Revolution (New York, 1991), eds. Alan Forrest and Peter

Jones, pp. 105-121.

D. M. G. Sutherland, France, 1789-1815: Revolution and Counter-Revolution (London, 1985), pp. 4968; 82-88; 126-131.

M. J. Sydenham, The French Revolution (London, 1965), pp. 105-107, 114-115, 155-164, 170-181,

199-214.

Gwyn Williams, Artisans and Sans-culottes: popular movements in France and Britain during the

French Revolution (London, 1968), ch. 2.

School of Humanities and Social Science

23

Week 8

23 April

The Terror:

Defence or Paranoia?

The problem

The fall of the monarchy did not resolve the problems that the Revolutionary government was faced

with. On the contrary, the dangers emanating outside of France as well as within became even greater.

Unity, which could have been achieved using the monarchical principle as a rallying force, was now

impossible. Mirabeau was dead, Lafayette had deserted, Barnave had been relegated to the background

and the Girondins were no longer able to control the popular movement. The Revolution seemed to be

lost, all the more so since the Prussians were on French soil and were approaching Paris. This was the

backdrop to the beginning of the darkest chapter in the Revolution, but is it an adequate explanation of

why the Terror came about?

Seminar theme

Was the Terror an aberration or an emergency response to the threat of foreign invasion and counter-revolution?

The Terror

David Andress, French Society in Revolution (Manchester, 1999), ch. 7.

William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (Oxford, 1989), ch. 11.

D. D. Bien, “François Furet, the Terror and 1789,” French Historical Studies, 16 (1990): 777-784.

Crane Brinton, “A Kind of Religious Faith,” in The French Revolution. Conflicting Interpretations

(Malabar, Fl., 1989), eds. F. A. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 193-204.

Richard Cobb, Reactions to the French Revolution (London, 1972), pp. 75-94.

Richard Cobb, “Some Aspects of the Revolutionary Mentality,” in New Perspectives on the French

Revolution (New York, 1965), ed. Jeffrey Kaplow, pp. 310-37.

Alan Forrest, The French Revolution (Oxford, 1995), pp. 64-70.

F. Furet and D. Richet, French Revolution (London, 1970), ch. 7.

F. Furet and M. Ozouf, A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (Cambridge, Mass., 1989), esp.

the articles on the Terror, Danton, Robespierre, Sans-culottes, and the Committee of Public Safety.

Hugh Gough, The Terror in the French Revolution (New York, 1998).

Norman Hampson, The Terror in the French Revolution (London, 1981). Historical Association

pamphlet.

N. Hampson, Danton (London, 1978).

N. Hampson, Saint-Just (Oxford, 1991).

Georges Lefebvre, “A Synthesis,” in The French Revolution. Conflicting Interpretations (Malabar, Fl.,

1989), eds. F. A. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 220-28.

Georges Lefebvre, The Coming of the French Revolution (Princeton, N. J., 1967), ch. 2.

Albert Mathiez, “A Realistic Necessity,” in The French Revolution. Conflicting Interpretations

(Malabar, Fl., 1989), eds. F. A. Kafker and J. M. Laux, pp. 187-192.

Peter McPhee, The French Revolution, 1789-1799 (Oxford, 2002), ch.7.

R .R. Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution (Princeton, 1970).

School of Humanities and Social Science

24

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution (New Jersey, 1998), ch. 5.

D. M. G. Sutherland, France, 1789-1815: Revolution and Counter-Revolution (London, 1985), ch. 6.

M. J. Sydenham, The First French Republic (London, 1974), ch. 1.

Timothy Tackett, “The Constituent Assembly and the Terror,” in The French Revolution and the

Creation of Modern Political Culture (Oxford, 1989), ed. Keith Baker, vol. 4, pp. 39-54.

Robespierre

Norman Hampson, The life and opinions of Maximilien Robespierre (London, 1974).

John Hardman, Robespierre (London, 1999), esp. ch. 8.

Colin Haydon and William Doyle (eds), Robespierre (Cambridge, 1999).

David P. Jordan, The revolutionary career of Maximilien Robespierre (New York, 1985).

George Rude (ed.), Robespierre (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1967).

George Rude, Robespierre: portrait of a Revolutionary Democrat (London, 1975).

J. M. Thompson, Robespierre and the French revolution (London, 1952).

The 9 Thermidor

John Hardman, Robespierre (London, 1999), esp. ch. 11.

Martyn Lyons, France under the Directory (Cambridge, 1975), ch. 1.

M. Lyons, “The 9 Thermidor: Motives and Effects,” European Studies Review, (1975),

Richard Bienvenu (ed.), The ninth of Thermidor: the fall of Robespierre (New York, 1968),

Georges Lefebvre, The Thermidorians (London, 1965).

Denis Woronoff, The Thermidorean regime and the directory, 1794-1799 (Cambridge, 1984).

School of Humanities and Social Science

25

Week 9

30 April

The Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte

The problem

On 9-10 November 1799 (18-19 Brumaire, year VIII), the government of the Directory was overthrown

by a military coup and Napoleon became First Consul. He was thirty years of age and was poised to

become master of France. To some historians, this event represents a disaster for the French people since

it was the beginning of a military dictatorship that, it is argued, destroyed a budding democracy. To

others, he restored the French people’s confidence in the future and brought order to a chaotic, violent

and faction ridden country. The people of Paris, in any event, tired of so many political upheavals, did

not react. Was the coup of Brumaire simply another in a long line of coups, or was it a break from the

revolutionary tradition? How did the common people in France react to the rule of Napoleon?

Seminar themes

What kind of man was Napoleon? What were some of the cultural and political factors that influenced

the formation of his personality?

Was Napoleon’s rise to power an accident, the consequence of his own unique genius, or more the

consequence of deep-rooted forces in French history?

Napoleon’s Early Years

Philip Dwyer, ‘From Corsican Nationalist to French Revolutionary: Problems of Identity in the

Writings of the Young Napoleon, 1785-1793’, French History 16 (2002): 132-52.

Geoffrey Ellis, Napoleon (London, 1997), ch. 2.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), chs. 1-3.

Harold T. Parker, “Napoleon’s Youth and Rise to Power”, in Philip Dwyer (ed), Napoleon and Europe

(London, 2001), pp. 25-42.

Harold T. Parker, “The Roots of Personality,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux, Napoleon and

His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 2-21.

Alan Schom, Napoleon Bonaparte (London, 1998), ch. 1.

The First Italian Campaign, 1796-97

T. C. W. Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars (London, 1996), chs. 5 and 7.

Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s military campaigns (Wilmington, Del., 1987), ch. 1.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), chs. 2 and

3.

Felix Markham, Napoleon (London, 1963), chs. 1-3.

J. M. Thompson, Napoleon Bonaparte (Oxford, 1958), chs. 2-3.

Egypt

T. C. W. Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars, ch. 6.

David Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (London, 1966), part 4.

J. Christopher Herold, Bonaparte in Egypt (London, 1963).

School of Humanities and Social Science

26

J. Christopher Herold, “Napoleon in Action: The Egyptian Campaign,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M.

Laux, Napoleon and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 22-36.

Felix Markham, Napoleon (London, 1963), ch. 4.

Paul Schroeder, The Transformation of European Politics, 1763-1848, pp. 177-182.

The Road to Brumaire

David Andress, French Society in Revolution (Manchester, 1999), ch. 8.

Malcom Crook, Napoleon comes to power: Democracy and dictatorship in revolutionary France,

1795-1804. (Cardiff, 1998), ch. 3.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), ch. 4.

Peter McPhee, The French Revolution, 1789-1799 (Oxford, 2002), ch. 8.

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution (New Jersey, 1998), ch. 6.

M. Rapport, “Napoleon’s Rise to Power,” History Today (1998), pp.

Reactions to the Coup of Brumaire

Albert Leon Guerard, “The Death of Liberty,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux, Napoleon and

His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 48-49.

Albert Vandal, “The Restoration of Order and National Unity,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux,

Napoleon and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 50-56.

School of Humanities and Social Science

27

Week 10

7 May

Napoleonic France:

Order and Stability

The problem

The Republican Consulate ended with the proclamation of the hereditary Empire in May 1804, and was

symbolically transformed into an empire with the crowning of Napoleon in December of that same

year. The First Empire, as it came to be known, was made up of French, but also of many non-French

speaking departments and was to reach its maximum point of expansion around 1811. In order to keep

the heterogeneous nature of the Empire together, it was necessary to introduce a uniform administration

and laws. It was these “tools of conquest”, as Stuart Woolf calls them, that enabled the Napoleonic

expansion to be carried out so effectively. This week we are going to look at a number of different

branches of this militaro-administrative complex and discuss what role each of these parts played in the

formation of the Empire.

Seminar themes

How did Napoleon consolidate his personal power in the years after Brumaire?

Why did Napoleon introduce the empire in 1804?

Napoleonic France

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution (New Jersey, 1998), ch. 7.

Geoffrey Ellis, Napoleon (London, 1997), ch. 3.

Isser Woloch, “The Napoleonic Regime and French Society,” in Philip Dwyer (ed), Napoleon and Europe

(London, 2001), pp. 60-78.

The Plebiscite

Claude Langlois, “The Voters,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux, Napoleon and His Times

(Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 57-65.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), ch. 9.

The Opposition

Geoffrey Ellis, Napoleon (London, 1997), pp. 53-59.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), ch. 10.

Eric A. Arnold, “Some Observations on the French Opposition to Napoleonic Conscription, 1804-1806,”

in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux, Napoleon and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 139-148.

Howard Brown, ‘From Organic Society to Security State: The war on brigandage in France, 1797-1802’,

Journal of Modern History 69 (1997), pp.

Gwynne Lewis, “Political brigandage and popular disaffection in the south-east of France 1795-1804,” in

G. Lewis and C. Lucas, eds, Beyond the Terror: Essays in French Regional and Social History, 17941815 (Cambridge, 1983), pp. 195-231.

Michael Sibalis, “The Napoleonic Police State,” in Philip Dwyer (ed), Napoleon and Europe (London,

2001), pp. 79-94.

School of Humanities and Social Science

28

Jean Vidalenc, “Opposition during the Consulate and the Empire,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M.

Laux, Napoleon and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 122-138.

The Concordat

Alphonse Aulard, ‘An Unnecessary Papal Victory,’ in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux, Napoleon

and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 86-90.

Geoffrey Ellis, Napoleon (London, 1997), pp. 59-66.

Jean-Marie Leflon, ‘A Compromise for Mutual Advantage,’ in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux,

Napoleon and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 72-85.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), ch. 7.

The Civil Code and the Administration

Geoffrey Ellis, The Napoleonic Empire (London, 1991), ch. 3.

Jacques Godechot, “Institutions,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux, Napoleon and His Times

(Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 278-295.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), chs. 6 and

8.

School of Humanities and Social Science

29

Week 11

14 May

Napoleon’s Conquest of Europe

The problem

Stuart Woolf argues that Michael Broers argues that it was Napoleon’s frustration with some of the

smaller European powers to implement the blockade against Britain that led him to expand the empire.

One could reasonably argue, therefore, that it was Britain’s refusal to accept French hegemony on the

Continent that caused the Napoleonic wars to go on for such a long period of time. I would argue, on

the other hand, that Napoleon was driven to conquer Europe for deep-seated psychological reasons that

we may never understand.

Seminar themes

Did Napoleon attempt to create a ‘united’ Europe?

Was he driven to conquer Europe for personal or for political-economic reasons?

Conquest

Jeremy Black, ‘Napoleon’s impact on international relations’, History Today, 48 (1998), pp. 45-51.

Michael Broers, Europe under Napoleon (London, 1996), ch. 1.

Philip Dwyer, “Napoleon and the Drive for Glory,” in Philip Dwyer (ed), Napoleon and Europe

(London, 2001), pp. 118-135.

Philip Dwyer, Talleyrand (London, 2002), ch. 4.

Geoffrey Ellis, Napoleon (London, 1997), ch. 4.

Charles Esdaile, The Wars of Napoleon (London, 1995), ch. 1.

David Gates, The Napoleonic Wars, 1803-1815 (London, 1997), ch. 3.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), chs 14 and

15.

Jeremy Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution (New Jersey, 1998), ch. 8.

The Continental Blockade

M. Anderson, “The Continental System and Russo-British Relations during the Napoleonic Wars,” in K.

Bourne and D. C. Watt, eds, Studies in International History (London, 1967), pp. 68-80.

Michael Broers, Europe under Napoleon (London, 1996), pp. 144-64.

François Crouzet, “A Serious Cause of Social and Economic Dislocation,” in Frank A. Kafker and James

M. Laux, Napoleon and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 179-191.

F. Crouzet, “Wars, Blockade and Economic Change in Europe, 1792-1815,” Journal of Economic History

24 (1964), pp. 567-588.

Geoffrey Ellis, The Napoleonic Empire (London, 1991), pp. 95-106.

Geoffrey Ellis, Napoleon (London, 1997), pp. 101-112.

Clive Emsley, British Society and the French Wars 1793-1815 (London, 1979), ch. 7.

Eli Heckscher, “A Challenge Easily Overcome,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux, Napoleon and

His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 170-178.

School of Humanities and Social Science

30

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994), pp. 214220.

Felix Markham, Napoleon (London, 1963), ch. 10.

J. Meyer and J. Bromley, “‘The Second Hundred Years’ War,’” in D. Johnson, F. Bédarida and F.

Crouzet, eds, Britain and France: ten centuries (Folkestone, 1980), pp. 168-171.

School of Humanities and Social Science

31

Week 12

21 May

The Fall of Napoleon

The problem

Although the empire continued to grow until about 1811, there was a marked decline in

Napoleon’s military success from about 1808 onwards. Among the causes are his two

greatest strategic mistakes — the Spanish and Russian campaigns. Both were brought about

by his obsession with enforcing the Continental Blockade. Also, by the time Napoleon had

reached the age of forty his physique and character had changed considerably. Although he

was still a hard worker, he had become tired and sick. He was still in possession of his

intellectual skills and had a prodigious memory, but power had transformed him. As First

Consul he had listened to people and taken their advice, but as the Empire progressed and as

some of the more capable men in his entourage were either killed or left him, his egoism and

an over exaggerated confidence in his own abilities led him to make some disastrous

decisions. He tolerated criticism less and less, believed that he was always right.

Seminar theme

How significant was the role played by guerrillas in bringing about the defeat of the French in

Spain?

What possessed Napoleon to take on Russia and think that he could win? The only other

person to have invaded Russia was Hitler. Can a comparison be made between Napoleon

and Hitler in their desire for European/world domination?

Why did Napoleon return from Elba? Why did the allies allow the restoration of the Bourbon

monarchy? What was the logic behind the new division of Europe in 1814-15.

How much did France and Europe change in the years 1799 to 1815 under Napoleon’s rule?

What impact did Napoleon have on France and Europe?

The Spanish Guerrillas

Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory (Wilmington, Del., 1987), ch. 7.

David Gates, The Napoleonic Wars, 1803-1815 (London, 1997), ch. 8.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994),

pp. 220-225.

Felix Markham, Napoleon (London, 1963), ch. 11.

Don Alexander, “The Impact of Guerrilla Warfare in Spain on French Combat Strength,”

Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Western Society for French History (1975), pp. 91103.

Charles Esdaile, “Heroes or Villains? The Spanish Guerrillas in the Peninsula,” History Today

38 (1988), pp. 29-35.

Charles Esdaile, “War and politics in Spain, 1808-1814,” Historical Journal 31 (1988), pp. 295317.

Richard Herr, “God, Evil and Spain’s Rising against Napoleon,” in R. Herr and H. T. Parker,

eds, Ideas in History (Durham, N.C., 1965), pp. 157-181.

School of Humanities and Social Science

32

John Lawrence Tone, “Napoleon’s Uncongenial Sea: Guerrilla Warfare in Navarre during the

Peninsular War, 1808-14,” European History Quarterly 26 (1996), pp. 355-382.

John Lawrence Tone, The Fatal Knot: The Guerrilla War in Navarre and the Defeat of

Napoleon in Spain (Chapel Hill, 1994), especially chs. 1 and 9.

The Invasion of Russia

Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory (Wilmington, Del., 1987), ch. 10.

Charles Esdaile, The Wars of Napoleon (London, 1995), ch. 8.

David Gates, The Napoleonic Wars, 1803-1815 (London, 1997), ch. 9.

Felix Markham, Napoleon (London, 1963), ch. 13.

Harold T. Parker, “Why did Napoleon invade Russia? A study in motivation, personality and

social structure,” Proceedings of the Consortium on Revolutionary Europe (1989), pp. 86-96.

David Chandler, “Napoleon’s Errors of judgement,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux,

Napoleon and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 246-55.

Janet Hartley, “Napoleon in Russia — Saviour or Antichrist?”, History Today 41 (1991), pp. 2834.

Napoleon, “A Freezing Winter,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M. Laux, Napoleon and His

Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 240-45.

Gunter Rothenberg, “Npaoleon: The Warrior and His Army,” in Frank A. Kafker and James M.

Laux, Napoleon and His Times (Malabar, Fl., 1989), pp. 230-39.

The Hundred Days

David Gates, The Napoleonic Wars, 1803-1815 (London, 1997), ch. 11.

Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (London, 1994),

ch. 19.

Pamela Pilbeam, “The ‘Restoration’ of western Europe, 1814-1815,” in Pamela Pilbeam, ed.,

Themes in Modern European History, 1780-1830 (London, New York, 1995), pp. 107-124.

School of Humanities and Social Science

33

Week 13

28 May

Seminars this week

will be devoted to preparation

for the trial

School of Humanities and Social Science

34

Week 14

4-5 June

Napoleon on Trial

The object of this exercise is to put into practise what you should have learnt during the semester. You

will put the French Revolution and Napoleon on trial. Half the class will take the ‘defence’ side,

arguing that the Revolution was a great achievement that brought democracy, and modernity, to the rest

of Europe and the world. The other half will take the ‘prosecution’ side, arguing that the Revolution

was a waste of time and that more people suffered than benefited from “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity,

which ring like empty phrases in the face of so much destruction and loss of life. Students will act out

the roles of witnesses, prosecution, defence, etc.

Each class member will research his or her role and be prepared to perform ‘in character’ during the reenactment.

You will have to do some research in the library to obtain the necessary background on your

‘character’. You should be prepared to look for additional sources on your own.

ATTENDANCE AT THE TRIAL IS OBLIGATORY!!!

Students missing the day of the trial will have to complete a substantial research paper.

For the Trial — Please Note

1.

Each class member will research his/her role and be prepared to perform ‘in character’

during the re-enactment.

2.

Each side must call all its witnesses. It is not necessary, however, that each witness be cross

examined. When being questioned, the witnesses MUST

a) Keep to the facts. This is a trial so no speechifying or flowery rhetoric will be tolerated.

b) Not invent material. If the court finds that the witness does not know his/her material, he/she

may be asked to stand down, eventually incurring a loss of points.

c) Not put on a phoney French or other accent.

3.

When advocates are conducting questioning they MUST:

a) Ask direct questions in order to receive direct answers. Do not ask leading questions.

b) Not badger the witness.

4.

Each side may bring notes, books, journals, articles, etc. to the trial and may have them

available at the lead advocate’s table. No notes will be allowed on the witness stand

although advocates may bring notes to the podium if they desire.

School of Humanities and Social Science

35

Witnesses

You may choose to represent any historical character (after consultation with the course coodinator),

but here is a list of suggestions:

FOR THE PROSECUTION:

Condorcet — scientist and revolutionary

Alexander I of Russia — Tsar of Russia

The marquise de La Tour du Pin — noble

Louis XVI — King of France

Marie-Antoinette — Queen of France

Jacques Necker — Louis XVI’s finance minister

The Pope (Pius VI and VII)

Frederick William III — King of Prussia

Talleyrand-Perigord, Charles Maurice de — Napoleon’s Foreign Minister

Wellington — British general

A soldier

A (German or Spanish or Italian) peasant

FOR THE DEFENCE:

Napoleon Bonaparte — Emperor of France

Georges Danton — deputy, revolutionary

David, Jacques-Louis — artist

Joseph Fouché — revolutionary, minister of Police

Olympe de Gouges — feminist revolutionary

Jean-Paul Marat — extreme left-wing revolutionary

Jacques Ménétra — a Parisian worker

Count Mirabeau — noble, revolutionary

The abbé Sieyès — deputy, revolutionary

Maximilien Robespierre — member of Committee of Public Safety

A soldier

A peasant

School of Humanities and Social Science

36

Issues to Consider

PROSECUTION

DEFENCE

Civil Constitution of the Clergy

Concordat

Imprisonment and execution of opponents

Code Napoleon

War with Britain in 1803

Treaty of Amiens

Censorship

Tax reform

Conscription

Efficient government

Condition of poor

Careers open to men with talent

Condition of the working classes

Emancipation of Jews

Peoples of Europe were exploited and oppressed

Constitutions/Liberalism to Europe

Constant war (atrocities, death toll)

Abolition of feudalism in conquered areas

Destruction of France’s economy

Religious toleration

Invasion of Spain, Russia

Condition of the peasantry

Stance towards women

Promoted Science

No creativity in the arts

Louvre/Opera

Immoral foreign policy

Restored order

Nationalism

Process to unify Germany/Italy (sort of)

The Revolution was a waste of time (France

would have become a modern, democratic state

eventually)

The Revolution became a beacon of hope for the

oppressed peoples of the world

School of Humanities and Social Science

37

Trial Format

INSTRUCTIONS FROM THE TRIBUNAL

OPENING ARGUMENTS:

Prosecution

Defence

CASE FOR THE PROSECUTION:

Examination

Cross-Examination

Re-direct

RECESS FOR LUNCH

CALL TO SESSION

CASE FOR THE DEFENCE:

Examination

Cross-Examination

Re-direct

CLOSING ARGUMENTS:

Prosecution

Defence

DELIBERATION

VERDICT

ADJOURNMENT TO GODFREY TANNER BAR

School of Humanities and Social Science

38

Trial Rules

Since I do not want the focus of this exercise to be on the ‘procedure’ of the trial, there are some ground

rules that should be observed.

A. Grounds for Objection

1. Germane: The question is beyond the bounds of due consideration, immaterial to the case

at hand. Particularly pertinent during cross-examination when witness is asked to answer

questions/address issues not raised in examination.

2. Hearsay: A matter to which the witness was not a direct witness.

3. Badgering: Abusive conduct intended to coerce statements evidencing a reckless disregard

for the truth or the dignity of the witness or the court.

B. Sanctions

1. Warning

2. Silencing of witness/lawyer

3. Citation of contempt and removal to the gallery

4. Expulsion — leading to a deduction of points from your mark

C. Requests to approach the bench should only be done in extreme cases

D. Requests for recess — Each side may request one 5-minute recess.

School of Humanities and Social Science

39

Major Essay Topics

Make sure you read this before you