6 F the Entrepreneur

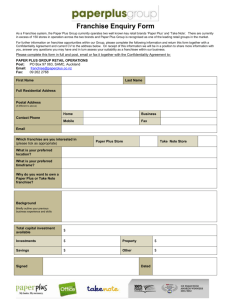

advertisement