Thesis - Teknisk Design

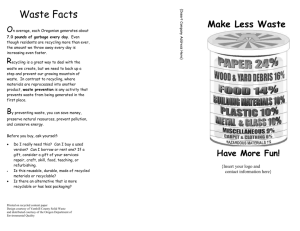

advertisement