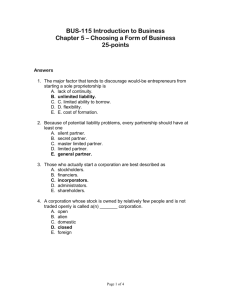

Business Organization and Combination

advertisement