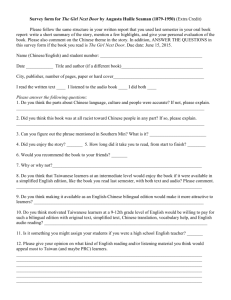

Chinese Cultural Values And Chinese Language

advertisement