Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

Interactivity and the Invisible: What Counts as

Writing in the Age of Web 2.0

William I. Wolff ∗

Associate Professor of Writing Arts, Rowan University, United States

Abstract

This study asks: what counts as writing in a Web 2.0 environment? How do the vocabularies, functionalities, and organizing

structures of Web 2.0 environments impact our understanding of what writing is in these spaces and how that writing is performed?

Results suggest that we, as scholars and teachers, need to pay more attention to, first, the interactivity that is embedded in and afforded

by Web 2.0 applications and, second, the processes that are invisible to the composer. Successful compositional engagement with

Web 2.0 applications requires an evolving interactive set of practices similar to those practiced by gamers, comics, and electronic

literature authors and readers. What we learn about these practices has the potential to transform the way we understand writing

and the teaching of writing within and outside of a Web 2.0 ecosystem.

© 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Comics; Electronic Literature; Gaming; Interactivity; Web 2.0; Writing; Writing Ecologies

1. Introduction

In the fall of 2009, as I was recording data for the study I discuss below, NCTE released Kathleen Blake Yancey’s

report, Writing in the 21st Century. The report was:

A call to action, a call to research and articulate new composition, a call to help our students compose often,

compose well, and through these composings, become the citizen writers of our country, the citizen writers of

our world, and the writers of our future. (Yancey, 2009, p. 1)

J. Elizabeth Clark (2010) argued that Yancey’s call marked a “new era” for our field, “a challenge to articulate

how technology is radically transforming our understanding of authors and authority and to create powerful new

practices to converge with this new digital world” (p. 27). For Yancey (2009), we have entered a “new era in literacy, a

period we might call the Age of Composition” wherein “our impulse to write is now digitized and expanded—or put

differently, newly technologized, socialized” (p. 5). Yancey’s and Clark’s calls echoed Selfe’s (1999) culturally and

socially situated redefinition of technological literacy (p. 10) and Yancey’s (2004) Conference on College Composition

and Communication Chair’s address during which she observed the field of composition studies has reached a liminal

moment: “Literacy today is in the midst of a tectonic change. Even inside of school, never before have writing and

composing generated such diversity in definition. What do our references to writing mean?” (p. 298). Indeed. To invoke

∗

Associate Professor of Writing Arts, Hawthorn Hall, Rowan University, 201 Mullica Hill Road. Tel.: +856 256 5221; fax: +856 256 5730.

E-mail address: wolffw@rowan.edu

8755-4615/$ – see front matter © 2013 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2013.06.001

212

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

Dorothy A. Winsor (1992), in the early decades of the twenty-first century—in the age of Web 2.0—what counts as

writing?

In 2007, I started asking my students to think about how Web 2.0 applications facilitate the exchange of information

across multiple websites. I soon began witnessing the challenges they were having with both conceiving of information

movement and composing to facilitate it. Since that time, I have suspected that writing in the age of Web 2.0 is

significantly more complex than writing was in the age of print and even in the early years of the visual browser.

Inspired by Winsor’s seminal article, “What Counts as Writing: An Argument from Engineers’ Practice” (1992), the

study I discuss in the following pages was designed to investigate if writing in a Web 2.0 environment is substantively

different from writing in more traditional print-based and computer environments. What, the study asks, counts as

writing in a Web 2.0 environment? How do the vocabularies, functionalities, and organizing structures of Web 2.0

environments impact our understanding of what writing is in these spaces and how that writing is performed?

Winsor was chosen to frame the study for three reasons. First, I saw the investigation as similar to Winsor’s; where

she was thinking about how people were writing in disciplines other than English studies, I was investigating how

writing is happening in a new environment. Second, Winsor challenged three myths we suspected we might have

to confront, as well, namely “that when we really write something, we think it up all on our own and do creative,

original, individual work” (1992, p. 338); “that writing requires the direct presence of human beings” (1992, p. 340);

and “that writing necessarily involves words” (1992, p. 342). Third, Winsor’s whole discussion suggested that writing

is essentially meaning making. That is, regardless of the form, genre, or method of writing, the primary goal of the act

of writing is to create meaning for a particular audience in a particular context.

Results from my study confirmed that the Web 2.0 spaces many in our field have been asking our students to compose

in (blogs, wikis, Twitter, and so on) are, indeed, spaces for writing that, like more traditional print-based writing, have

their own grammars, styles, and linguistics. More importantly, results also suggest that we, as scholars and teachers

need to pay more attention to, first, the interactivity that is embedded in and afforded by Web 2.0 applications and,

second, the processes that are invisible to the composer. Paying attention to interactivity and what is invisible to the

user is something that gamers do (think of using Mario to find hidden coins). Authors and readers of comics (McCloud,

2005) and electronic literature (Hayles, 2008) focus on the interactivity and invisibility embedded in their texts. Study

results suggest that we as a field need to start thinking about how one composes in Web 2.0 environments in terms

of the relationships between writing and gaming (Colby & Colby, 2008), writing and comics (Mueller, 2012), and

writing and electronic literature (Grigar, 2005). Too often the theories and practices associated with Web 2.0, gaming,

comics, and electronic literature (elit), are discussed separately in our scholarship and in our classrooms (and, in the

case of comics and elit, tangentially, if at all). This can no longer be the case. Web 2.0 is causing these fields and their

associated user practices to merge. In the twenty-first century, effective and successful compositional engagement with

Web 2.0 applications—Yancey’s “new composition”—requires an evolving interactive set of practices similar to those

practiced by gamers and comics and elit authors and readers. What we learn about these practices has the potential to

transform the way we understand writing and the teaching of writing within and outside of a Web 2.0 ecosystem.

2. Study methodology

This study was designed to catalog the functions and writing spaces within Web 2.0 applications, investigate how

those functions and writing spaces were implemented across Web 2.0 applications, and identify function and writing

space relationships among Web 2.0 applications.1 The study included the following phases:

• Create a master list of English language Web 2.0 applications (September 2008). The master list was created by

cataloging and crosschecking Web 2.0 applications from the following websites: Go2Web20 <http://go2web20.net>,

Alexa <http://alexa.com>, and Movers 2.0 <http://movers20.esnips.com/>. Go2Web20 is one of the largest, if not

the largest, directory of Web 2.0 applications. Alexa tracks, ranks, and provides robust data on worldwide website

usage. Movers 2.0 ranks the top 100 Web 2.0 applications according to their usage by accessing the Alexa API.

1 This study was made possible by a Rowan University Non-Salary Financial Support Grant (2008–2009). Two former Rowan University undergraduate research assistants, Katherin Fitzpatrick and Rene Youssef, played significant roles in data collection and analysis and as such, the Results

section is written in the plural.

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

213

Table 1

Purposive Sample and Function Totals.

Web 2.0 Application

Total Functions

Web 2.0 Application

Total Functions

Bebo

Blogger

Dailymotion

Delicious

Digg

Esnips

Facebook

Feedburner

Flickr

Fotolog

Friendster

hi5

imeem

Last.fm

Linkedin

Livejournal

40

31

30

24

26

33

43

15

34

26

31

32

33

29

23

37

Meebo

Metacafe

Multiply

MySpace

Ning

Orkut

Skype

Slide

Tagged

Technorati

Twitter

Wikia

Wikipedia

Xanga

Youtube

25

29

44

48

46

37

24

31

34

21

30

26

15

44

38

• Generate random and purposive samples (September 2008). From the master list, random samples with 90%, 95%,

and 99% confidence intervals were created, as was a purposive sample (random samples were generated for use in

possible later stages of the study). If a Web 2.0 application appeared on the master list, Alexa’s Top 500, and Movers

2.0, the application was added to the purposive sample. Other Web 2.0 applications could be added if researchers

thought they would create a more accurate survey of activities associated with Web 2.0.

• Analyze the purposive sample (September 2008–August 2009). One of the challenges faced when analyzing Web

2.0 applications is that the applications are constantly changing by adding, removing, or altering core and minor

functions. As a result, we developed a Reflexive Cataloging Methodology as a means to capture and record changes

over a period. In a Reflexive Cataloguing Methodology, a researcher or group of researchers catalogs data from the

sample population at set points over a period of time, checking to see if the population has changed in any way. In

our study, we cataloged and then met to discuss data from the purposive sample once a month for twelve months.

• Consider whether functions can be considered writing (June 2009–July 2009). Researchers assessed each of the

functions identified and tagged in terms of Winsor’s (1992) descriptions, theories, and conclusions in “What Counts

as Writing? An Argument from Engineers’ Practice” to determine whether a particular function could be considered

a kind of writing.

3. Results

3.1. Create a master list of English language Web 2.0 applications and create sample populations

As of September 2008, Go2Web20 contained 2,663 Web 2.0 applications in their database. We identified 89 English

language Web 2.0 applications in the Alexa Top 500 list that were not on the Movers 2.0 list, and 25 English language

Web 2.0 applications on the Movers 2.0 list that were not on the Alexa Top 500 list. When all three lists were combined

and 36 duplicates removed, the resulting list contained a full population of 2,741 English language Web 2.0 applications.

Random populations of 368 (90% CI), 491 (95% CI), and 750 (99% CI) were generated.

We generated a purposive sample of 29 applications by identifying applications that appeared in the full population,

Alexa’s Top 500, and Movers 2.0 (Table 1). Two applications, Blogger and Delicious, were added to the purposive

sample because we thought it important that blogging and social bookmarking be represented, and they were the leading

sites in those areas. In September 2008, Alexa ranked Twitter the 972nd most popular website and Movers 2.0 ranked

it the 39th most popular Web 2.0 application. By March 2009, however, Alexa ranked Twitter at 80 (a 92% increase)

and Movers 2.0 ranked it at 10 (a 74% increase). NielsonWire reported Twitter use had increased 1,382% between

February 2008 and February 2009 (McGiboney, 2009). In short, Twitter could no longer be ignored. We opted to add

214

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

Twitter to the purposive sample and remove MyYearBook—a site with a target population younger than college-aged

students.

3.2. Analyze the purposive sample

Between September 2008 and August 2009, we identified 69 unique functions associated with the Web 2.0 applications in the purposive sample (Table 2). Each of the functions was tagged with a particular name and given a definition,

creating a unique vocabulary, or “collabulary,” for our tagging, archiving, and research purposes. Only two functions

(creating an account and user-generated content) were found in all 31 Web 2.0 applications (Table 1). MySpace was

identified as having the most functions (N=48), followed by Ning (N=46), Multiple and Xanga (N=44), and Bebo and

Facebook (N=40). Wikipedia (N=15) and Feedburner (N=15) had the fewest. In other words, results suggested that for

a user to use MySpace effectively, they needed to know how to identify, understand, and use 48 unique functions; to

use Facebook effectively, 40; and so on.

Identifying and defining functions resulted in many challenges, especially because similar terms (e.g., Groups,

Communities, Networks) were used across applications but were often implemented in different ways (see also boyd,

2006). Consider Groups, which the majority (61%) of the applications in our sample had. We define Groups as multiple

users who have gathered for a specific interest or purpose. Most applications labeled their groups Groups, and their

groups functioned in ways that informed the definition we created. Others, however, did not. Xanga labeled their groups

“Blogrings.” Wikia called their groups “Wikis”; Orkut, Esnips, and Livejournal, labeled their groups “Communities.”

We, however, define a Community as a user-created space within which other users can create groups. Fewer

applications (23%) in our sample had that kind of community. As Wolff, Fitzpatrick, and Youssef (2009) have written

elsewhere:

[T]he Esnips homepage labels as communities what other sites might label as groups. LiveJournal announces

that it has a “true sense of community” where users can “join user-created communities centered around [their]

interests to share information and meet new friends. From art to zombies, if you can think of it, there’s probably

a community about it” (“Quick Tour”). LiveJournal, then, itself embodies the idea of community and also allows

users to create and to join specific communities that explore a specific topic that in turn contribute to the site’s

proclaimed community feel. Ultimately, LiveJournal communities are quite similar to other sites’ groups.

Further challenging our ability to create definitions, many applications (e.g. Flickr, Last.FM, YouTube) refer to themselves as Communities in their Terms of Service. This self-definition as a Community confronts what people typically

refer to Web 2.0 application as: Networks. We define Networks as a group of people organized by location, a definition

that must be differentiated from SocialNetworks (groups of people connected online that for the most part knew each

other in person prior to online) and SocialNetworking (groups of people connected online that for the most part did not

know each other in real life beforehand)—definitions informed in large part by danah m. boyd and Nicole B. Ellison

(2007).

3.3. Consider whether functions can be considered writing

Results of our analysis suggest 73.9% (51 of 69 functions) of what users do in a Web 2.0 environment counts as

writing (Table 2). These functions include more traditional forms of writing that use words and sentences, such as

blogging, forum writing, chatting online, and composing in wiki spaces composition. But, they also expand what can

be considered writing to include, for example:

•

•

•

•

•

•

customizing the layout of personal space in application (tag: designlayout)

controlling who has access to content one creates (tag: contentsecurity)

updating constantly of user activity within application (tag: newsfeed)

subscribing to another’s content in order to receive updates (tag: subscription)

adding to one’s account games and other apps for entertainment or other purposes (tag: application)

embedding media within a page, post, or other writing space (tag: embedding)

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

215

Table 2

Web 2.0 Function and Characteristic Tags, Definitions, and whether Tag Activity Counts as Writing.

Function / Characteristic Tag

Function Definition

Date Added (Definition

Revised)

Count as Writing or a

Writing Space? (Y/N)

account

The ability to become a member of the site or

application.

The ability to designate age appropriateness of

content.

The ability to add to one’s account games and

other apps for entertainment or other purposes

(such as Facebook apps).

Plugins that were designed by an application

(and not a third party) that can be added to

another application (and not the toolbar).

Applications that have created their own

monetary currency that must be purchased by

the user in order to purchase certain things on

the site.

The ability to upload a visual representation of

one’s self.

An area for expanded writing of a personal

nature.

The ability to create topics that organize content.

Real-time P2P messaging involving two people.

Public critique or the space for such.

A user-created space within which other users

can create groups.

The ability to control who has access to content

one creates.

The ability to design social network-like

communities.

The ability to create groups within social

networks.

The ability to create social networks.

The ability to customize the layout of personal

space in application.

The application connects directly with external

applications to help users share content or

connect with other users (such as when sites

connect users to YouTube so they can embed

video).

The ability to download desktop application that

will interact with online application.

The ability to download applications to cell

phone that will interact with online application.

The ability to draw sketches or pictures in a

specifically designated space and make them

public or private.

The ability to have content from this site

embedded in another site. This is not the same as

sharing.

The ability to embed media within a page, post,

or other writing space (not to be confused with

uploading content)

The ability to save content to the desktop.

The ability to classify someone as a family

member.

Those who are following content but who’s

content is not necessarily followed in return.

The ability to post to discussion/message boards

that are often divided by topic.

9.24.08

Y

11.17.08

Y

9.24.08 (7.21.09) (8.9.09)

Y

7.30.09

N

11.19.08

N

9.24.08

Y

9.27.08

Y

10.13.08

9.24.08

9.24.08

10.20.08 (11.12.08)

Y

Y

Y

11.17.08

Y

11.12.08

Y

11.12.08

Y

2.18.09

10.13.08

Y

Y

10.13.08

N

11.19.08

N

11.19.08

N

11.17.08

Y

6.2.09

Y

9.24.08

Y

10.13.08 (11.19.08)

7.21.09

Y

Y

7.21.09

N

9.24.08

Y

ageappropriatesetting

applications

applicationdesignedplugin

applicationspecificcurrency

avatar

blogspace

categories

chat

comments

communities

contentsecurity

createcommunities

creategroups

createnetworks

customelayout

directapplicationconnection

downloadapplicationtodesktop

downloadapplicationtophone

drawingspace

embeddable

embedding

exportcontent

family

followers

forums

216

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

Table 2 (Continued)

Function / Characteristic Tag

Function Definition

Date Added (Definition

Revised)

Count as Writing or a

Writing Space? (Y/N)

friends

Other users with an ostensible relationship to

you that you reciprocate.

Real-time P2P messaging involving more than

two people.

Multiple users who have gathered for a specific

interest/purpose.

The ability to use HTML when generating

content.

The ability to import bookmarks from another

application.

Private electronic mail within a Web 2.0

application.

Succinct update of occurrences or personal

status.

A group of people organized by location.

A constant update of user activity within

application.

Comments about an item written to provide

further information about the item (should be

distinguished from comments).

Connects with users’ OpenID login information.

The ability to add extras to a site to increase its

functionality and the users experience.

The ability to upgrade to a most robust account

that has certain features, such as storage space.

The ability to create a space to disclose limited

personal information.

The ability to control access to one’s profile.

Public messaging.

A quantified judgment of content.

An application provides the opportunity to

update others of new content sent via RSS.

The ability to search the site or application.

The application has opened its API for outsiders

to search.

The application integrates with users Google,

Hotmail, Yahoo! or other email account to help

user connect with others they may know.

The ability to see who is following your content.

The ability to send content to users/other people

often via external application.

The ability to create a slideshow of photographs.

Groups of people connected online that for the

most part knew each other in person prior to

online.

Groups of people connected online that for the

most part did not know each other in real life

beforehand.

The ability to subscribe to another’s content in

order to receive updates.

Suggestions that the application gives the user as

opposed to searching the email for it.

The ability to label various texts using keywords.

The ability to compose a tagline for a specific

space.

A public list of activities organized over time.

9.24.08

N

10.9.08

Y

9.24.08

N

10.13.08

Y

10.13.08

Y

9.24.08

Y

9.24.08

Y

2.18.09

9.24.08

Y

10.13.08

Y

10.13.08

7.21.09 (8.9.09)

N

Y

10.29.08 (7.21.09)

Y

9.24.08

Y

11.17.08

9.24.08 (7.21.09)

9.24.08

9.24.08

Y

Y

Y

Y

9.24.08

7.21.09

Y

Y

9.24.08

N

10.13.08 (7.21.09)

9.24.08

N

Y

7.21.09

10.13.08

Y

N

10.13.08

N

10.13.08 (7.21.09)

Y

8.8.09

N

9.24.08

11.12.08

Y

Y

7.21.09

Y

groupchat

groups

htmluse

importbookmarks

messaging

microblog

network

newsfeed

notes

openID

plugins

premiumaccount

profile

profilesecurity

publicmessaging

rating

RSSfeed

search

searchableAPI

searchemailforotherusers

seefollowers

share

slideshow

socialnetwork

socialnetworking

subscription

suggesteduser

tagging

tagline

timeline

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

217

Table 2 (Continued)

Function / Characteristic Tag

Function Definition

Date Added (Definition

Revised)

Count as Writing or a

Writing Space? (Y/N)

toolbarembed

The application has toolbar that embeds in web

browser to ease interaction with the site.

The ability to translate site to into one or more

foreign languages.

An ID that provides access to multiple areas

within a particular application. Not the same as a

login ID or Open ID.

The ability to add content to an application via

email.

The ability to add content to an application via

cell phone.

The ability to upload media documents other

than video, photo, and music.

The ability to post your own music content.

The ability to post your own photo content, not

including avatar photos.

The ability to post your own video content.

Content made by users of application rather than

the creator/moderator of the application.

A box that holds applications, often able to be

moved around the page.

An online writing space that can be edited by

more than one user.

9.27.08

N

10.29.08

Y

10.29.08

N

10.13.08

Y

10.13.08

Y

10.13.08

Y

9.24.08

9.24.08

Y

Y

9.24.08

9.24.08

Y

Y

10.29.08

N

9.27.08

Y

translation

uniqueID

uploadcontentviaemail

uploadcontentviacellphone

uploaddocs

uploadmusic

uploadphoto

uploadvideo

usergeneratedcontent

widget

wikispace

Each of the functions identified as a form of writing, or characteristic identified as a writing space, plays a role in

the creation of meaning for the writer and/or a specific audience. Further research needs to be conducted in order to

more fully understand the various processes associated with these new forms of writing, which we suspect involve a

host of rhetorical, practical, and ethical decisions.

4. Writing in the age of Web 2.0

Dale Daugherty and Tim O’Reilly invented the term “Web 2.0” to “capture the widespread sense that there’s

something qualitatively different about today’s web” (O’Reilly, 2005). Bradley Dilger (2010) has provided a thorough

review of the origination of and subsequent controversy over the definition of Web 2.0 (on the topic of controversy,

see also Jarrett, 2008; Scholz, 2008; Silver, 2008; Zimmer, 2008). He suggested “to truly understand Web 2.0 style

... we should seek to understand the relationships between truth, presentation, writer, reader, thought, and language

that Web 2.0 embodies” (p. 17). Others have also suggested we can better understand Web 2.0 and how to teach

writing within it by considering how it affords relationships among teachers, students, and texts. Stephanie Vie (2008),

for example, advocated for the integration of social networking sites in the composition classroom to reduce “the

deepening digital divide” (p. 11) between composition instructors and their students. Brian Jackson and Jon Wallin

(2009) and Geoffrey V. Carter and Sarah J. Arroyo (2011) discussed the importance of YouTube for teaching students

about rhetorical and social opportunities afforded by participatory composition. James Purdy (2009) and James J.

Brown, Jr. (2009) suggested Wikipedia is a space where students can problematize traditional ideas about authority,

collaboration, and revision (Purdy) and intellectual property (Brown). Dànielle Nicole DeVoss and James Porter (2006)

considered how file sharing affected writing instructors and challenges us to re-think traditional plagiarism policies.

Christopher Schmidt (2011) applied the cartography metaphor to writers who are composing in multimodal new media

environments. Kevin Brooks (2002) proposed a genre-based pedagogy for teaching creative hypertext because “our

discipline is, for the most part, still trying to figure out ways to encourage innovative and sophisticated means of

writing on the Web” (p. 337). Jeff Rice (2005) suggested a “pedagogy of the home page” after questioning, “What is

it about the home page that makes it a form of writing? Where does the home page belong in writing instruction?”

(p. 61). Complicating the rhetorical, theoretical, and pedagogical concerns discussed in the previous small sample

218

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

(see also Day, McClure, & Palmquist, 2009) are, as study results suggest, the pragmatic challenges users face when

using Web 2.0 applications. These include, but are certainly not limited to, learning new vocabularies, recognizing the

characteristics of new writing spaces that contain multiple symbiotic genres, conceiving of the relationships among

multiple applications, and being able to transfer knowledge of functionality and style from one application to the next.

In order to grasp the implications of these findings, I suggest we go back to O’Reilly and Daughtery’s (O’Reilly,

2005) observation that Web 2.0 is inherently different from the Web prior to Web 2.0—what some have labeled Web

1.0. Web 1.0 was the time of hypertext—a series of online documents connected by hyperlinks. Linking, however, was

primarily site-specific. That is, major news and business websites did not link out to other websites, nor did usability

theories encourage them to do so. Indeed, the field of usability emerged from a website designer’s desire to find the best

way possible to encourage readers to stay within a particular domain; if they were able to navigate a site successfully,

they would not purchase products or consume information elsewhere:

Simply stated, if the customer can’t find a product, then he or she will not buy it. The Web is the ultimate

customer-powering environment. He or she who clicks the mouse gets to decide everything. It is so easy to go

elsewhere; all the competitors in the world are but a mouseclick away. (Nielsen, 1999, p. 9)

(It is important to note that although Jakob Nielsen defines usability in terms of market rhetoric, and virtually all of

his examples are commercial, not all websites’ primary goals are making money and keeping users within a particular

domain. Course websites, for example, often contained links to other websites).

It is easy to forget what the typical web page looked like in 1999, the year Nielson published his seminal Designing

Web Usability (and, coincidentally, the year Blogger was launched). Layouts were sparse, heavy with links to other

parts of the site, light on images, and formatted for 15-inch monitors. Video was rarely used; YouTube would not launch

for another six years. Users came to expect different domains would have different navigations, and though some basic

link names like “home” and “news” would be familiar from one news site to the next, there was no expectation of

overlap from one site to the next. Users learned how to navigate sites individually, learned how to click on their links

and read their chunks of text, and then move along. Nor was there significant linking from major news sites to websites

related to that news. For example, in 1999, one did not see and did not expect there to be links from a New York

Times article about the Lewinsky scandal to The White House website (Figure 1). Websites were silos. Like VCRs,

books, and CDs, websites were discrete entities within a larger media system. Each hard-to-navigate website, like each

hard-to-program VCR and each confusing microwave, was its own individual product. This is the great irony of Web

usability theory: it encouraged isolation within a system designed for interactivity.

Flash-forward a decade. Websites now employ multiple cognitive artifacts (Norman, 1991), writing spaces, and,

possibly, burgeoning genres. In the age of Web 2.0, successful sites facilitate the exchange of information between and

among other sites. This stands in stark contrast to the siloed websites of Web 1.0 and the isolationist criteria that inform

traditional usability theories. They are Interactive Domains—spaces in which users engage not only to read what is on

the screen, but to compose, communicate, create, share, and so on. Each of the 69 Web 2.0 functions and characteristics

identified in the study are examples of or facilitate that interaction in one way or another. This is why it is so difficult

to know what descriptor to use when discussing Web 2.0. Are they websites or applications or, perhaps, we should

just call them platforms? Perhaps they are ecologies in Margaret A. Syverson’s (1999) sense of the word, or even

genre ecologies (Spinuzzi, 2002). With all of the interactivity afforded by Facebook, MySpace, and YouTube, calling

them websites seems archaic, anachronistic, and not completely correct. The phrase Interactive Domains borrows from

Gee’s (2007) semiotic domains and hints toward their ecological screen-scapes. In semiotic domains, “words, images,

symbols, and artifacts have meanings that are specific to particular ... contexts” (p. 25). They have “design grammars”:

“principals and patterns in terms of which one can recognize what is and what is not acceptable or typical content in

a semiotic domain” (p. 28). The ecosystem that exists within the role-playing game, Zelda, for example, is a semiotic

domain filled with artifacts users need to decipher within the game’s context and grammars. So, too, is Super Mario

Bros., Ms. Pac Man, Galaga, even Pong. Each game ecology, like each Web 2.0 ecology, has to be read, learned, and

understood within its particular context and informed by a user’s prior gaming experience and knowledge.

Consider the issue of website vocabularies—the terms and names used for a site’s organizational structures and

interactive features. Usability theory has shown that naming portions of websites well, such as navigation menu items,

is vitally important for users to have a successful experience with a particular website. As such, the organizational

structures, the classification systems that lead to them, and the link names users click on to navigate them are not benign

website window dressing. Rather, they are rhetorical constructs that structure and shape a user’s experience with a

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

219

Figure 1. The New York Times and The White House websites in 1999.

This figure represents the layout of websites in 1999 and also highlights the lack of direct linking between websites.

particular site—for better or worse depending on a user’s prior knowledge and web experience. The interactive and

user-generated features of Web 2.0 have brought users the new challenge of understanding new vocabularies within

the context of particular sites. These vocabularies can, for example, consist of familiar words, such as “Feed” and

“Post,” which mean something quite different from their traditional, off-line meanings. Other familiar words, such as

“Groups” or “Communities,” as discussed above, become challenging because they are often employed in different

ways on different sites. Or, there are new, acronym-heavy terms, such as, HTML, RSS, and API, that might hold little,

if any, prior meaning for users.

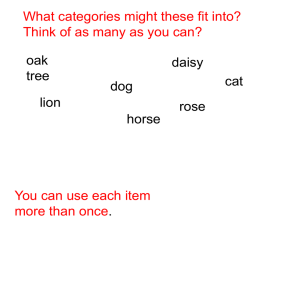

Many of these terms are associated with a user’s interaction. For example, in the blog application, Wordpress, a

user can click on an HTML tab in the Add New Post blog post screen (Figure 2) and compose using HTML tags.

The HTML tab is just one of many functions that present composing opportunities and challenges in the Add New

Post screen. The area has multiple symbols (a chain link, a musical note, a filmstrip) and terms (post, tag, html) that

challenge users to define in praxis and, as study results suggest, provide multiple avenues for writing. The chain link

provides the opportunity to create a hyperlink (tags: usergeneratedcontent, htmluse); the musical note provides the

opportunity to upload music (tags: uploadmusic, embedding). The filmstrip provides the ability to embed video (tags:

embedvideo, embedding). Posting (tag: blogspace), tagging (tag: tagging), and HTML (tag: htmluse) are all forms of

writing. Users also need to become familiar with the medium of blogging (tag: blogspace), the many genres associated

with blogging, as well as the functionalities and authorial implications of using the blog writing space (Rettberg, 2008).

Furthermore, users should be aware of how blogs interact with other Web 2.0 applications via RSS (tag: RSSfeed) and

other programming languages (for example, tag: searchableAPI) to facilitate the movement of content between and

among applications, and an understanding of how to use them within the context of a particular action, such as:

finding, retrieving, storing, and re-accessing a certain bit of information. Each Web 2.0 application (domain, ecology)

challenges users in a similar way by asking them to learn new terms, comprehend new symbols, engage with new

writing spaces, recognize relationships among multiple applications, and transfer knowledge from one application to

the next—all of which contribute to the interactive complexities of what it means to write in this new environment.

These interactive complexities are almost identical to those found in video games, as Edmund Y. Chang (2008), citing

220

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

Figure 2. Wordpress Add New Post Screen.This figure shows the varied writing spaces, symbols, and functionalities on the Wordpress blog Add

New Post screen.

Alexander Galloway (2006), argued, “Writing, then, must also be action. Writing must also be both object and process.”

Galloway continues:

Without action, games remain only in the pages of an abstract rule book. Without the active participation of

players and machines, video games exist only as static computer code. Video games come into being when the

machine is powered up and the software is executed; they exist when enacted. (p. 2)

Similarly, without action, writing would only remain in the abstract, in the mind, in the rules of grammar, genre, and

composition. Without the active engagement of writers (also with machines), writing exists only as ideas, outlines,

brainstorms. Writing comes into being when the mind is powered up, critical thinking and language routines executed;

writing, too, only exists when enacted, when pen is put to paper, idea turned into word. Writing cannot only be learned

by reading or by hearing or by rote rules and lines but by doing, practicing, revising, and rewriting.

One of the important consequences of the ubiquity of active interaction is that sites that have not been considered

Web 2.0 are taking on some of these interactive qualities. Consider, for example, the 2010 New York Times online article

“Hydraulic Leak Cited as Possible Cause of Spill” (Figure 3). Immediately to the right of the opening paragraph, a

menu bar asks users to choose from the following options: sign in (tag: account), recommend the article (tag: rating),

post to Twitter (tag: share), add comments (tag: comments), email the article, send to your iPhone, print, get reprints,

and, share (tag: share). If you click on Share, you see options for LinkedIn, Digg, Facebook, Mixx, MySpace, Yahoo!,

Buzz, and permalink. When a user clicks on the Twitter link, a Post to Twitter window appears just to the right. The

writing space contains the title of the article, a nyti.ms shortened URL, and space for the user to add more information

(tag: microblog, usergeneratedcontent). The user then clicks Post and the tweet is sent to the user’s Twitter stream

where their followers will see it and, perhaps, click on the link to see the article. The cycle can then continue.

Traditional websites are not the only spaces that are becoming interactive domains. Dynamic toolbars, toolbar

buttons, and plugins are making the web browser itself an interactive domain that can be manipulated, organized,

and customized. The browser can be composed. For example, a user can install a toolbar (tag: toolbarembed) for the

social bookmarking and annotating service, Diigo <http://diigo.com>, that links their actions to their Diigo account

(tag: account) (Figure 4). When on a web page users would like to bookmark (tags: share, importbookmarks), they

can click on the toolbar button that reads Bookmark. This results in a popup window that contains writing spaces for

the web page URL and Title (tag: usergeneratedcontent); space to enter a Description (tag: usergeneratedcontent):

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

221

Figure 3. 2010 New York Times website with Post to Twitter Functionality.This figure illustrates the processes of posting to Twitter and highlights

the interactive features of a more traditional website.

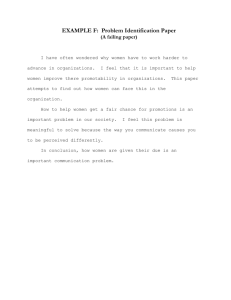

Figure 4. The Visibility and Invisibility Associated with Bookmarking a website.

This figure depicts the processes associated with bookmarking a website, including which parts of the process are visible and invisible. It also

suggests that some of the processes are forms of writing. (Eye and Eyelid image from Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. Pencil icon from

http://library.thinkquest.org/J001156/pencil2.gif).

space to enter Tags (tags: usergeneratedcontent, tagging), Used Last Time, and Recommended Tags; check boxes to

indicate privacy settings (tag: contentsecurity); Save, Save and Send (tag: share), and Cancel buttons; and the option to

tweet your bookmark (tag: microblog, usergeneratedcontent), Add to a List, or Share to a Group (tag: groups). After

entering their information, they choose Save and Send. The information is sent to their Diigo account where, if set to

public, other Diigo users will be able to read it. Further, if someone subscribes to the user’s bookmark’s RSS feed (tag:

RSSfeed), the information for the new bookmark is sent to and will appear in the latter person’s RSS feed reader.

222

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

Though seemingly simple as we look at the figures and read the narrative descriptions, the processes are really quite

complex, employing multiple signs (Hall, 2007), requiring a significant amount of prior knowledge and familiarity

with multiple Web 2.0 application functions (more, it should be pointed out, than were even identified by studying the

purposive sample). Users need to know what Twitter and Diigo are and must have an account already set up. They have

to know what a browser toolbar is and that toolbars can be edited. They need to know how to install toolbar buttons

and how to work effectively within the constraints of the provided writing space. They need to know what social

bookmarking is, how tagging works, and what happens to the information when it appears on Diigo and another’s RSS

feed reader.

Web 2.0 constantly challenges users’ abilities to engage with and conceive of the invisible. When users post

something to Twitter or Facebook from within a third-party page or create a Diigo bookmark from an embedded

toolbar, they must have a conception of what is going to happen with their data after they click Send. In other words,

users must be thinking about what is not seen while interacting with what is in front of them. This visible/invisible

dyad is similar to what Scott McCloud (1994, 2005) observed about the role of the gutter in comics. The gutter “plays

host to much of the magic and mystery that are at the very heart of comics! Here in the limbo of the gutter, human

imagination takes two separate images and transforms them into a single idea” (McCloud, 1994, p. 66). Within that

transformation is a:

Balance between the visible and the invisible.... Comics is a kind of call and response in which the artist gives

[the reader] something to see within the panels, and then gives [the reader] something to imagine between the

panels. (McCloud, 2005)

The visible/invisible dyad is at work in video games, like Super Mario Bros., when users have to conceive of hidden

coins to reveal; and, in Zelda, where users have to grasp the goals of the quest and find hidden objects without an aide

other than the ecosystem itself. When websites were silos, little was hidden; the links, text, navigation were all there on

a user’s screen, and link addresses were visible in the status bar and/or by viewing the page source. Users knew there

were other websites to go to, but they did not have a significant impact on how users used the site they were currently

on.

Web 2.0 interactivity and information sharing; however, requires users to conceive constantly of what is not there,

in front of them, on their screen, at that time. When users click the Bookmark button in an embedded Diigo toolbar,

they must have an awareness of the events that will take place that are invisible to them: that the bookmark will appear

in their Library and possibly the RSS feed of someone who subscribes to their bookmarks (Figure 4). That is, they need

to have (if not an understanding of how information can move between websites) an awareness that information does

move between websites and which applications will help facilitate that process more effectively for their rhetorical

goals and practical needs. These more complex computational characteristics of Web 2.0 greatly expand compositional

possibilities and have the potential to help students become more digitally sophisticated writers.

N. Katherine Hayles (2008) observed:

Literature in the twenty-first century is computational.... The computational nature of twenty-first century literature is most evident... in electronic literature. More than being marked by digitality, electronic literature is actively

formed by it. For those of us interested in the present state of literature and where it might be going, electronic

literature raises complex, diverse, and compelling issues. In what sense is electronic literature a dynamic interplay

with computational media, and what are the effects of these interactions? Do these effects differ systematically

from print as a medium, and if so, in what ways? How are users embodied interactions brought into play when

the textual performance is enacted by an intelligent machine? (pp. 43–44)

Replace the phrase “electronic literature” with “Web 2.0” and the singular word “literature” with “writing,” and we

begin to see the overlap between questions raised about elit and those raised here in response to Web 2.0. In what

sense is Web 2.0 “a dynamic interplay” among humans and semiotic domains and semantic databases? How are users’

utterences (in, for example, spaces like Facebook and Twitter) “brought into play” when their writing is enacted by

semiotic domains and semantic databases? What makes the processes described above so complex (especially for

students who for the most part are not technologically sophisticated) is that users do not see the movement on their

screens; this is not like entering a URL into an address bar and seeing the web page emerge before your eyes. Rather,

the movement of data—the computation—happens behind the scenes, facilitated by various programming languages

and computer processes. According to Hayles, “[c]omputation is not peripheral or incidental to electronic literature

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

223

Figure 5. An Ecology of Composition in a Web 2.0 Ecosystem.

This figure shows the ecosystem of complex, overlapping, and evolving interactivities that are writing in the age of Web 2.0.

but central to its performance, play, and interpretation” (p. 44). Computation is also central to writing in the age of

Web 2.0. And we need to know much more about it and how to incorporate it into our writing pedagogy.

5. Conclusion

Writing in the age of Web 2.0 exists within an ecosystem of dynamic, overlapping, and evolving interactivities that

require the following from each user (Figure 5):

•

•

•

•

An understanding of new terms and signs in context (feed, module, page, widget).

An understanding of the functionality of the space (what happens when text is entered and button clicked).

Prior knowledge of multiple applications, how to install them, and how they work across platforms.

The ability to recognize when applications have changed and how to adapt to those changes (e.g., Facebook Terms

of Service).

• The ability to recognize when to use what applications in context of a particular action (such as, finding, retrieving,

storing, and accessing information).

• An understanding of when to use which mode of composition (image, video, audio, alphabetic text, code)

Web 2.0 applications require a sophisticated, reflective, elastic, semiotic, aural, eco-spatial, electratic (Rice &

O’Gorman, 2008; Ulmer, 2002), evolving information [interactivity]. I place square brackets around the word interactivity because it is too soon to name a term that encapsulates all of what I have described above. But whatever

that term might be, I strongly suspect it will be grounded in theories and ideas in the areas of gaming (Bogost, 2008;

Wardrip-Fruin & Harrigan, 2006; Wark, 2007), comics (Groensteen, 2007; McCloud, 1994; Varnum & Gibbons, 2007),

and electronic literature (Hayles, 2008; Dene, 2005). Web 2.0 applications are interactive computational ecosystems,

and within them, I find Yancey’s “new composition”—a composition that has more in common with video games,

comics, and electronic literature than traditional print-based alphabetic texts and hypertext. If we as a community are

going to more fully understand the compositional implications of this new composition—of the diverse and evolving

ways students write in, interact with, and think through Web 2.0 (not to mention the radically different dimensions text

will embody as touch screens, 3D, and 4D become ubiquitous)—we need to shift our perspective from seeing them

as spaces that afford multiple writing genres to seeing them for their visible and invisible diversity, complexity, and

interactivity. For this is what counts as writing in the age of Web 2.0.

William I. Wolff is an Associate Professor of Writing Arts at Rowan University, where he teaches courses on visual rhetoric, new media, and the

history and technologies of writing. Find him on Twitter @billwolff. He would like to thank his former undergraduate research assistants, Kathleen

Fitzpatrick and Rene Youssef, for their dedication to and work on this study. He would also like to thank the blind reviewers for their close readings

and insightful suggestions.

224

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

References

Bogost, Ian. (2008). Unit operations: An approach to videogame criticism. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

boyd, danah m. (2006). Friends, friendsters, and MySpace top 8: Writing community into being on social network sites. First Monday, 11(12).

Retrieved July 21, 2010, from http://www.firstmonday.org/issues/issue11 12/boyd/

boyd, danah m., & Ellison, Nicole B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1). Retrieved March 15, 2009, from http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol13/issue1/br.ellison.html

Brooks, Kevin. (2002). Reading, writing, and teaching creative hypertext: A genre-based pedagogy. Pedagogy, 2(3), 337–356.

Brown, James J., Jr. (2009). Essjay’s ethos: Rethinking textual origins and intellectual property. College Composition and Communication, 61(1),

238–258.

Carter, Geoffrey V., & Arroyo, Sarah J. (2011). Tubing the future: Participatory pedagogy and YouTube U in 2020. Computers and Composition,

28(4), 292–302.

Chang, Edmund Y. (2008). Gaming as writing, or, World of Warcraft as World of Wordcraft. Computers and Composition Online. Retrieved from

http://www.bgsu.edu/cconline/gaming issue 2008/Chang Gaming as writing/index.html

Clark, J. Elizabeth. (2010). The digital imperative: Making the case for a 21st -century pedagogy. Computers and Composition, 27(1),

27–35.

Colby, Richard, & Rebekah Shultz Colby. (2008). Reading games: Composition, literacy, and video gaming [Special issue]. Computers and

Composition Online. Retrieved from http://www.bgsu.edu/cconline/gaming issue 2008/ed welcome gaming 2008.htm

Day, Michael; McClure, Randall. & Palmquist, Mike. (2009). Composition in the freeware age: Assessing the impact and value of the Web 2.0 movement in the teaching of writing [Special issue]. Computers and Composition Online. Retrieved from http://www.bgsu.edu/departments/english/

cconline/Ed Welcome Fall 09/compinfreewareintroduction.htm

Dene, Grigar. (2005). The challenges of hybrid forms of electronic writing. Computers and Composition, 22(3), 375–393.

DeVoss, Dànielle Nicole, & Porter, James. (2006). Why Napster matters to writing: Filesharing as a new ethic of digital delivery. Computers and

Composition, 23(2), 178–210.

Dilger, Bradley. (2010). Beyond star flashes: The elements of Web 2.0 style. Computers and Composition, 27(1), 15–26.

Gee, James P. (2007). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Second Edition: Revised and Updated Edition (2nd ed.). New

York City: Palgrave Macmillan.

Groensteen, Thierry. (2007). The system of comics. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Hall, Sean. (2007). This means this, this means that: A user’s guide to semiotics. London: Laurence King Publishers.

Hayles, N. Katherine. (2008). Electronic literature: New horizons for the literary (1st ed.). Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Jackson, Brian, & Wallin, Jon. (2009). Rediscovering the “back-and-forthness” of rhetoric in the age of YouTube. College Composition and

Communication, 61(2), W374–W396.

Jarrett, Kylie. (2008). Interactivity is evil!: A critical investigation of web 2.0. First Monday, 13(3). Retrieved July 14, 2010, from

http://firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2140/1947

McCloud, Scott. (1994). Understanding comics: The invisible art. New York City: Harper Paperbacks.

McCloud, Scott. (2005). Scott McCloud on comics. Retrieved August 15, 2010, from http://www.ted.com/talks/scott mccloud on comics.html

McGiboney, Michelle. (2009, March 18). Twitter’s tweet smell of success. NielsonWire. Retrieved July 17, 2010, from http://blog.nielsen.com/

nielsenwire/online mobile/twitters-tweet-smell-of-success/

Mueller, Derek. (2012). Tracing rhetorical style from prose to new media: 3.33. Kairos Praxis Wiki. Retrieved February 17, 2012, from http://kairos.

technorhetoric.net/praxis/index.php/Tracing Rhetorical Style from Prose to New Media: 3.33 Ways

Nielsen, Jakob. (1999). Designing web usability (1st ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Peachpit Press.

Norman, Donald A. (1991). Cognitive artifacts. In John M. Carroll (Ed.), Designing interaction: Psychology at the human-computer interface (pp.

17–38). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Reilly, Timothy. (2005). Not 2.0? Retrieved March 7, 2009, from http://radar.oreilly.com/archives/2005/08/not-20.html

Purdy, James P. (2009). When the tenets of composition go public: A study of writing in Wikipedia. College Composition and Communication,

61(2), W351–W373.

Rettberg, Jill W. (2008). Blogging. Cambridge: Polity.

Rice, Jeff. (2005). Cyborgography: A pedagogy of the homepage. Pedagogy, 5(1), 61–75.

Rice, Jeff, & O’Gorman, Marcel. (2008). New media/New methods: The academic turn from literacy to electracy. West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press.

Schmidt, Christopher. (2011). The new media writer as cartographer. Computers and Composition, 28(4), 303–314.

Scholz, Trebor. (2008). Market ideology and the myths of Web 2.0. First Monday, 13(3). Retrieved July 14, 2010, from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/

cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2138/1945

Selfe, Cynthia L. (1999). Technology and literacy in the twenty-first century: The importance of paying attention. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois

University Press.

Silver, David. (2008). History, hype, and hope: An afterward. First Monday, 13(3). Retrieved July 14, 2010, from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/

cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2143/1950

Spinuzzi, Clay. (2002). Modeling genre ecologies (pp. 200–207). Toronto, Ontario, Canada: ACM Press.

Syverson, Margaret A. (1999). The wealth of reality: An ecology of composition. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

Ulmer, Gregory L. (2002). Internet invention: From literacy to electracy. New York City: Longman.

Varnum, Robin, & Gibbons, Christina T. (2007). The language of comics: Word and image. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

Vie, Stephanie. (2008). Digital divide 2.0: “Generation M” and online social networking sites in the composition classroom. Computers and

Composition, 25(1), 9–23.

W.I. Wolff / Computers and Composition 30 (2013) 211–225

225

Wardrip-Fruin, Noah, & Harrigan, Pat. (2006). First person: New media as story, performance, and game. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Wark, McKenzie. (2007). Gamer theory. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wolff, William I., Fitzpatrick, Katherin, & Youssef, Rene. (2009). Rethinking usability for Web 2.0 and beyond. Currents in Electronic Literacy,

Retrieved August 17, 2010, from http://currents.cwrl.utexas.edu/2009WolffFitzpatrickYoussef

Winsor, Dorothy A. (1992). What counts as writing? An argument from engineers’ practice. Journal of Advanced Composition, 12(2), 337–347.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2004). Made not only in words: Composition in a new key. College Composition and Communication, 56(2), 297–328.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. (2009). Writing in the 21st century. Retrieved February 10, 2012, from http://www.ncte.org/library/

NCTEFiles/Press/Yancey final.pdf

Zimmer, Michael. (2008). Preface: Critical perspectives on Web 2.0. First Monday, 13(3). Retrieved July 14, 2010, from http://firstmonday.org/htbin/

cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/2137/1943