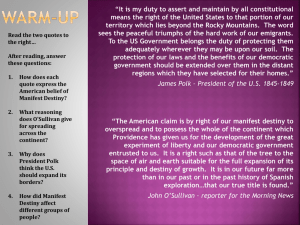

Sample Lesson - New Jersey Center for Civic Education

advertisement