India, Adi Dasgupta - International IDEA

advertisement

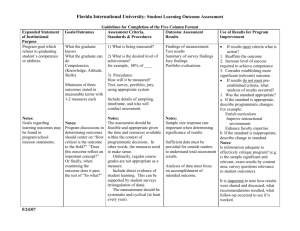

Extracted from Programmatic Parties © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2011. International IDEA, Strömsborg, 103 34 Stockholm, Sweden Phone +46-8-698 37 00, Fax: +46-8-20 24 22 E-mail: info@idea.int Web: www.idea.int 3 India 3.1 Introduction This case study of programmatic party politics in India focuses on two major transformations, one at the national level and the other at the state level. At the national level, India's party system has experienced fragmentation since the late 1980s, when the decades-long hegemony of the Congress Party began to give way to heated multi-party competition. The Congress Party's cadre programmatic party model—in which the programmes formulated by party elites were not important to the way that the party mobilized voters—has been challenged by parties such as the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) and a range of regional parties. Many of these newer parties have clear programmatic elements, yet they defy conventional categories by combining programmatic platforms with targeted ethnicity-based appeals to voters. On the one hand, these parties can be argued to represent an improvement on the Congress model because they bridge the gap between elite and mass party politics. Conversely, the often divisive nature of these parties’ strategies is not always conducive to stability in a large and diverse democracy such as India. However, there is evidence that over time these parties have moderated their emphasis on identity and as a result are becoming less 'ethnic' in their style of politics. In other words, they are in a process of becoming ‘ethnic–programmatic’ parties. At the sub-national level, over the last two decades chief ministers and political parties have emerged seeking to win elections by advocating programmes of economic development and good governance at the state level. The strategies employed by such parties are a stark contrast to the norm of vote buying and clientelism—or 'patronage democracy'—that has characterized Indian state elections for decades. These 'good governance' parties are reforming India's state-level politics and have brought about real democratic gains both in terms of accountability and government performance. States led by such programmatic parties have experienced dramatic improvements in terms of economic growth and the quality of public services, and good governance parties have been electorally successful as a result. Taken together, these two trends represent a virtuous cycle that has encouraged other parties to adopt the model. What explains the rise of ethnic–programmatic parties at the national level in India? The story begins with the institutional decay of the Congress Party, which created opportunities for new political entrepreneurs to enter the party system. But economic liberalization has also been significant, reducing the central government's monopolistic control over economic and political resources and thereby undermining the capacity of the ruling party’s clientelistic linkages to deliver electoral dominance. This dual process undermined the foundations of the Congress regime and opposition parties took advantage of this window of opportunity to develop electoral linkages and programmes that tapped the latent social cleavages that Congress—for decades an 'umbrella' party that had embraced a wide range of disparate social groups and interests—had failed to capitalize upon. As new parties such as the BJP developed into credible national contenders, however, the pressures of competitive party politics encouraged them to moderate their identity politics in order to expand beyond the relatively narrow support bases that first brought them to prominence—leading to a second evolution that has resulted in the emergence of nascent ethnic–programmatic parties. What explains the rise of 'good governance' programmatic parties at the state level in India? The decentralization of economic policymaking authority and resources associated with economic liberalization made it feasible for political leaders to run on 63 the basis of good governance campaigns—which carried little weight when states lacked the capacity to affect these policy areas. The growing inter-state competition for private investment has magnified the reward for pursuing pro-growth policies. At the same time, we must leave space for individual agency. It was the emergence of a handful of political leaders, such as Chandrababu Naidu, who understood that the new economic and institutional context brought with it opportunities for a new kind of politics, that kick-started the process of programmatization in India. Once these individuals had emerged, demonstration effects meant that parties and voters in other states quickly learnt of the economic benefits of ‘good governance’ parties—and their electoral success. It was not long before similar developments began to play out in other states across the country. India, the world's largest democracy, thus offers a number of valuable lessons about programmatic party politics. First, programmaticity is a complicated quality and may emerge in more ‘civic’ or more ‘ethnic’ variants—some of which may be less normatively desirable than others. Second, it suggests that although the political transition from single-party dominance to multi-party competition in socially diverse countries often results in the emergence of parties based around social and territorial cleavages, over time political competition can induce leaders to moderate their identity politics, giving rise to ethnic–programmatic parties. Third, it reveals that institutional reforms matter. Decentralization was a necessary, if not sufficient, condition for the evolution of more programmatic approaches at the state level. Fourth, it illustrates that economic reforms can have an important impact upon programmaticity, especially when they reduce the resources available for non-programmatic forms of linkage, such as patron–client ties, and place leaders under greater pressure to deliver. Finally, the Indian case highlights the importance of demonstration effects in the spread of programmatic party politics, and so has much to tell us about how programmatic gains become consolidated. 3.2 History of Programmatic Politics in India India has experienced nearly continuous democracy—with a brief interruption during the 'Emergency' period from 1975 to 1977—since independence in 1947. Yet India's political party system has undergone steady evolution since independence: from an era of 'pluralistic' single-party dominance by the Congress Party under Jawharlal Nehru (1947-1967) during which there was substantial competition within the party (Kothari 1964), to a period (1967-1984) of 'authoritarian' single-party dominance by the Congress Party, when power was centralized under Indira Gandhi (Bose and Jalal 2004), to the present, post-economic liberalization phase of multi-party competition phase (1991-present) in which power has alternated between coalition governments led by the Congress Party and the BJP, respectively. A graph of the distribution of seats in the Lok Sabha—the lower house of India's legislature—from the 1950s to the present day, illustrates these recent developments (Figure 3). Historically, a hallmark of India's national political party system has been the combination of coherent and distinctive party programmes, formulated by party elites, with highly clientelistic and populist electoral strategies (Brass 1994). In large part, this is the product of Congress rule. Under India's first Prime Minister, Jawharlal Nehru, the independence movement–turned political party articulated a clear programmatic commitment to state-led development and industrialization (Guha 2007). Yet support for this programme was purchased largely on the basis of a hierarchical patron–client network that extended into India's local districts (Weiner 1967). To this day, the Congress Party remains a quintessential 'cadre programmatic party'. 64 Figure 3: Party Seat Shares in the Lok Sabha, 1951–2009 Sources: Election Commission of India Since economic liberalization in 1991 and with the simultaneous decline of Congress Party hegemony, new entrants to the national party system have begun to pursue alternative forms of political organization. Initially, these parties carved out spaces for themselves on the basis of ethnic appeals. The BJP, now a credible national alternative to Congress, has risen to power largely based on the ideology of hindutva, Hindu nationalism, which has successfully attracted voters away from the secular Congress Party (Kohli 2001). Other parties have appealed to caste identities, such as the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), a quasi-regional low-caste political party, or to linguistic/territorial identities, as has been the case with a number of regional parties. While these parties do offer coherent, distinct and stable political programmes and appeal to voters on that basis, they also tend to target specific ethnic groups rather than the general electorate— an approach which, overall, is in many respects programmatic but may nonetheless be deleterious to national identity. However, some of these new parties appear to be curtailing their emphasis on ethnicity in favour of widening the scope of their electoral appeal, suggesting that they are in a process of evolving from ethnic parties into ethnic– programmatic parties. A second important trend has emerged at the state level. From the mid-1990s onwards, political parties in a number of states have aggressively campaigned on prodevelopment and 'good governance' platforms, won landslide election victories, and implemented successful reforms once in office. The paradigmatic case is Bihar—one of India's very poorest states that for decades was synonymous with criminalized, clientelistic politics and economic stagnation—which, following the election of reformist chief minister Nitish Kumar in 2005, experienced annual growth above 11 per cent and a genuine improvement in the quality of government (Economist 25 Nov 2010; New York Times 10 April 2010). While Kumar has garnered the greatest amount of media attention, he is only the latest in the fast-growing list of state-level chief ministers (and their political parties) that have adopted such a programmatic strategy. This process actually began a decade earlier with the rise of Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu and the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) in Andhra Pradesh during the 1990s (Rudolph and Rudolph 2001). Although the ‘good governance’ party model has yet to spread to all of 65 India's states, the emergence of politically successful programmatic parties committed to good governance represents a paradigm shift in India's state-level politics. 3.3 Conceptualization and Description of Programmatic Parties India does not feature classic ‘programmatic parties’. However, it does feature a number of political parties that, in different ways, have embraced aspects of a programmatic platform or mobilization strategy. Congress, a cadre–programmatic party, adopts programmatic policy platforms even though it rallies support through clientelistic strategies, while ethnic–programmatic parties such as the BJP and BSP establish linkages to voters by formulating stable ideological positions but their policies disproportionately benefit some ethnic communities (a term that is here used as a shorthand for religious, regional, linguistic and caste identities) over others. Congress: the cadre–programmatic party Kothari (1964) has characterized the two decades of Congress dominance that followed independence in 1947 as representing the emergence of the 'Congress System', a term intended to capture pluralistic governing style of Jawharlal Nehru, the immensely popular prime minister and leader of the Congress Party. Though opposition parties possessed few seats in the national or state legislatures, they played a large role in political debates and often influenced policy (Guha 2007). Similarly, though Nehru wielded immense personal control over the party, he often accommodated opposing views within the party, and generally pursed a consensus-oriented centrist political strategy. It was this approach that underpinned the emergence of the cadre– programmatic political machine that the Congress Party epitomizes to this day. Nehru and the Congress Party leadership advocated and implemented an economic strategy of state-led development and industrialization based on a succession of ‘fiveyear plans’ (Chhibber and Kollman 2004). Yet this economic programme, the major agenda of the Congress Party, played little role in the way the party connected to voters—which was instead based primarily on a hierarchical network of patronage that extended into India's districts (Weiner 1967). In the words of Mitra: ‘Soon after independence, the Congress co-opted landed gentry, businessmen, peasant proprietors, new industrialists and the rural middle class—socially and economically entrenched groups in society—into its organization. This provided the party with a strong and ready structure of support, with electoral 'link men' who controlled various 'vote banks', serviced through patronage’ (2011: 306). Thus, the Congress Party was programmatic in its policymaking but clientelistic in its electoral linkages. The disjuncture remains. For example, the dramatic liberal economic reforms initiated by the Congress Party that dismantled India's decades-old licensing and state-directed economic system from 1991 onward never emerged as an election issue. In Varshney's words: 'In a survey of mass political attitudes in India conducted in 1996, only 19 per cent of the electorate reported any knowledge of the economic reforms that had been implemented, even though the reforms had been in existence since 1991. In the countryside, where more than 70 per cent of Indians then lived, only about 14 per cent had heard of the reforms (compared with 32 per cent of voters in cities). Economic reforms were a non-issue in the 1996 and 1998 parliamentary elections. In the 1999 elections, the biggest reformers either lost or did not campaign on pro-market platforms' (2007: 102). Similar observations have been made about the disconnect between elite economic policymaking and mass politics in India by other researchers (see Kohli 2006). 66 There is also a striking disconnect between the party’s programme and the way that it organizes itself. This is reflected in the way that Congress handles the question of party leadership, which since Nehru has been transferred dynastically, with minimal recruitment of grassroots political talent. Shortly after Nehru's death power was transferred to Indira Gandhi, Nehru's daughter, who surrounded herself with sycophants and de-institutionalized the Congress Party (Kohli 1991); then to Rajiv Gandhi, Indira Gandhi's son, who served a short stint as prime minister but died early in his political career; then within a few years to Sonia Gandhi, Rajiv Gandhi's widow, who was elected leader of the Congress Party in 1997; and most recently to Rahul Gandhi, Sonia Gandhi's son, a Congress Party MP who is widely expected to replace his mother as party leader in the very near future. The Bharatiya Janata Party: an ethno–programmatic party The BJP controlled only two seats in the Lok Sabha in 1984. In the 1998 general elections, the party earned a total of 178 seats, enough to form a coalition government with a collection of regional allies. It is now viewed as a credible national alternative to the Congress Party and has successfully formed national coalition governments in 1996 and 1998–2004. Its rapid political ascent has been associated with its ability to appeal to Hindu voters in the Hindi-speaking northern belt of India. But its strong organizational base and committed cadre of grassroots workers has enabled it to forge effective links with voters beyond that constituency as well. Over time, the BJP has shed the religious nationalism that brought it to power in favour of a more secular, nationalist image. The BJP's origins can be traced to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a Hindu social movement founded in 1925. An offshoot of its predecessor party, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the BJP was founded in 1980 and until the late 1980s remained a relatively minor force in national party politics. However, by providing a political face for the controversial efforts of Hindu nationalists to demolish an Islamic mosque built allegedly on top of an holy ancient Hindu site in the town of Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh, the party was catapulted to national influence in the early 1990s (Jaffrelot 2007). The BJP has been able to appeal to a number of different constituencies using a number of different types of appeals. The party’s commitment to hindutva, Hindu nationalism, and the adoption of policies that were popular among India's northern upper-caste Hindu voters, such as ‘religious legislation’ in the shape of bans on the slaughter of cows and religious conversion, has been central to its rise. More troubling still, in certain states such as Gujarat BJP governments have either tacitly supported or turned a blind eye to anti-Muslim riots and violence. Unlike the Congress Party, which has historically been something of a 'catch-all', secular, centrist party, the BJP has traditionally drawn its leadership and membership from a relatively specific constituency: upper-caste Hindus in northern India (Basu 2012). Yet at the same time, the BJP has made direct ideological and programmatic appeals to voters on the basis of a more assertive foreign policy, fewer affirmative action benefits for minorities and disadvantaged groups and a coherent national economic plan. Both in terms of the party’s platform and linkage to voters, then, the BJP has displayed some of the characteristics of both a programmatic and an ethnic party. The same is true when it comes to the way that the BJP is internally organized and formulates policy. As with Congress, the BJP is a hierarchically organized party with power heavily concentrated in the hands of a few party leaders. But in contrast to Congress, these leaders tend to be drawn from its core ethnic base. Moreover, unlike the elite programmes of the Congress Party, the BJP's Hindu nationalist ideology serves not 67 only as an organizing principle for the policy programmes devised by party elites but is also ardently adhered to by the party's grassroots workers and is an important component of how the party links to voters and recruits its leaders (Thachil 2011). For example, the BJP leadership is comprised primarily of lifelong political activists, such as LK Advani and Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the first BJP prime minister, who have extensive grassroots experience. Indeed, Basu (2012) describes the BJP as a 'cadre-based mass party', linked to voters through a highly disciplined and ideological organization of party workers and social organizers. As it evolved into a national political contender, the BJP began to downplay its public emphasis on religious sectionalism in favour of casting itself as a clean and nationalistic alternative to the Congress Party. Significantly, each time the BJP has come to power it has implemented policies that have emphasized its ability to lead on national issues. India carried out major nuclear weapons tests in 1998 under the leadership of a BJP-led coalition government and a BJP government took an assertive foreign policy stance visà-vis Pakistan and led India to victory in the Kargil War with Pakistan in 1999. Furthermore, the BJP's stints in office have demonstrated that the BJP is a capable policymaking organization; BJP-led governments have overseen the passage of sophisticated economic policy reform measures, including the Fiscal Responsibility and Budgetary Management Act, a landmark deficit reduction measure, and the Special Economic Zones Act, a major deregulatory measure (World Bank 2005; Panagariya 2004). It is worth noting that, while the BJP continues to employ the rhetoric of economic nationalism, in reality it supports the same liberal economic reforms originally implemented by the Congress Party and embraces globalization, which party leaders view as the contemporary route to greater international power and status (Jaffrelot 2007; Basu 2011). The BJP thus possesses stable programmatic commitments that form the basis for the link between the party and voters, differentiate it from its principal rival, the Congress Party, and define the policies the party implements once elected to office. Although it may once have been an ethnic party, the BJP has moved away from solely stressing ethnic/religious themes. In its discourse, however, and some of its policies, it continues to pander to the preferences of Hindu voters, partly due to the fact that it continues to maintain linkages with Hindu social movements such as the RSS. The BJP thus appears to be best characterized as an ethnic–programmatic party. The Bahujan Samaj Party Regional and caste parties have also proliferated with the decline of Congress Party hegemony. Though individually not as influential as either the BJP or Congress, collectively these parties have played an important role during the 1990s and 2000s as allies of the Congress Party and BJP in alternating coalition governments. Although small, such parties have often been pivotal members of their coalitions and national elections have been won and lost based on their performance (Palshikar 2012). A prominent example is the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), a quasi-regional low-caste party that has experienced considerable political success. Based primarily in Uttar Pradesh, India's largest state, the BSP experienced an impressive rise in electoral success during the 1990s, earning 21 Lok Sabha seats in the 2009 general elections, up from just three seats in the 1991 general elections. The BSP was founded in 1984 by Kanshi Ram, a Dalit (the 'lowest' caste in the Hindu caste system) caste social activist. Originally a party of Dalits, the BSP has fashioned electoral success over time by expanding its scope, bringing together as an electoral bloc a disparate collection of constituencies: Dalits, minorities, including Christians, Muslims, 68 and the tribal population, as well as other arguably disadvantaged groups, such as the 'Other Backwards Castes' (OBCs). It has brought these different groups together under the moniker of 'Bahujans', or 'the deprived majority', a little-used term it has adopted and propagated. The party has fashioned itself as a party of the downtrodden and the party that stands against the dominance of high-caste Hindus (Hasan 2002). Like the BJP, which also emerged from a social movement, the BSP is notable for its extremely strong grassroots party organization, which has helped to mobilize voters to the party’s cause (Jaffrelot 1998). The BSP party subscribes to a distinct and coherent programme of Bahujan empowerment. A major pillar of the party's programme is 'reservations', or affirmative action policies, for disadvantaged groups and greater government spending in disadvantaged communities. When Mayawati, the immensely charismatic leader of the BSP, became Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh in 1995, she directed government spending and benefits toward Dalit villages, as promised: ‘Mayawati is popular […] because during her tenure as CM a number of welfare measures for Dalits were undertaken […] the land 'pattas' which had not been allotted to Dalits during the emergency but not given, were actually distributed among them; “pucca” roads linking the villages to the main road, construction of houses, drinking water pumps and toilets in the SC sections of the villages; pensions for old persons […] were some of the schemes implemented’ (Jaffrelot 2007a). Mayawati has also delivered less socially targeted goods, such as rural electrification (Min 2010). But at the same time, she is notorious for her alleged corruption, cronyism and strong-arm politics, which together with patron–client ties form the basis of the way that the party creates links with voters in the absence of an effective formal party organization and institutionalization. Given the BSP’s sectional foundation and clientelistic structure it is tempting to dismiss it as a non-programmatic party. However, in many ways constructing a support base around ethnicity and caste in the Indian context is analogous to mobilizing on the basis of class in the European context. This is because in India communal forms of identity such as caste play an important role in structuring the life chances of an individual. Most obviously, caste and socio-economic status are highly, though not perfectly, correlated. As a result, mobilizing support on the basis of ‘the deprived majority’ does not simply represent an attempt to capitalize upon ethnic politics. Rather, it reflects the attempt to establish a more equal and just political and economic system, and therefore bears comparison to the appeals of leftist parties in Europe to the working-class vote in order to pursue widespread economic reform. Thus, while the BSP displays some characteristics of a clientelistic and ethnic party, its broad appeal can also be said to have a clear programmatic component. Indeed, Stokes (2007) has referred to electoral linkages of this kind as ‘programmatic redistributive linkages’. Moreover, like the BJP, the BSP has over time sought to widen the scope of its appeal to voters. Initially a party of the Dalits, over time the BSP has expanded to include other disadvantaged groups as noted above. It now describes itself as the party of 'Bahujans', which does not correspond to any ethnic group in particular but to the disadvantaged more generally. A favourite metaphor of BSP leaders analogizes India to a ballpoint pen, where the tip of the pen represents the dominant castes, and remaining length represents the downtrodden 85 per cent that the BSP seeks to represent (Jaffrelot 1998: 38). Such metaphors convey a political ideology which is divisive but which is also national is scope and goes beyond mere ethnic appeals. This is well illustrated by the party’s recent attempt to bring Brahmins, members of the highest Hindu caste, into its fold by organizing party rallies for Brahmin voters (Tripathi 2007). 69 The BSP is associated with a clear and cohesive ideology and programme of Bahujan empowerment. It differentiates itself from rivals such as the Congress Party and the BJP on that basis, uses these appeals to form links to voters, and implements pro-Bahujan policies when elected to (thus far, state) office. So although the party has been criticized for being polarizing and divisive—some commentators have termed Mayawati the 'antiObama' in reference to her allegedly divisive political style—and continues to display characteristics of being an ethnic and clientelistic party, the BSP also advocates an important programmatic position. As a result, the BSP represent a new type of ethnic– programmatic political party that is threatening to displace the old Congress Party model of cadre programmatic politics in India's national party system. Table 6: Indian Party Profiles Party Name Party organization Party Linkages Party type Congress Party Strong elite party organization. Weak grassroots party organization. High policymaking capacity. Programmatic and clientelistic linkages nationwide. Cadre– programmatic Bharatiya Janata Party Strong elite party organization. Strong grassroots party organization. High policymaking capacity. Ethnic and programmatic linkages nationwide. Ethnic– programmatic Bahujan Samaj Party Mediocre elite party organization. Strong grassroots party organization. Medium policymaking capacity. Ethnic, clientelistic and programmatic linkages, some national reach but mainly in Uttar Pradesh. Ethnic/clientelist –programmatic State-level politics: the rise of 'good governance' parties While national politics only became competitive from the late 1980s onward, party politics in India's states have been open for much longer. State politics has traditionally been a highly clientelistic affair, with elections fought and won on the basis of patronage rather than policy programmes (Wilkinson 2007). This is epitomized by India's southern states, where parties of regional notables, such as the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) in Tamil Nadu, compete in 'bidding wars' for the mass vote—making innovative offers of goods, such as free electricity, free bicycles, cash, gold, alcohol and other items, in exchange for votes. In reference to such practices, Chandra goes so far as to term India a 'patronage democracy' (2004). In this political and historical context, one of the most notable but under-studied recent developments in Indian politics from the 1990s onward has been the rise of state-level parties and chief ministers committed to programmes of 'good governance' and economic development. These parties and chief ministers have been elected largely on the basis of their programmatic appeals—though some forms of traditional politics have invariably persisted. When in office they have implemented policies in line with their 70 promises. Frequently, these policies have been successful, and the parties have been returned to office with strong mandates. This emerging paradigm can perhaps be traced to the victory of the Telugu Desam Party (TDP) and the selection of Chandrababu Naidu as chief minister of Andhra Pradesh in 1995. Naidu came to power with an electoral campaign based heavily on promises of economic development and pro-growth policies. This electoral strategy was a genuine innovation in state-level politics, particularly in the context of poor states in which clientelism has tended to be particularly rampant. As Rudolph and Rudolph (2001) note, Naidu swiftly became an ‘icon’ for liberal state-level economic reforms and economic modernization in India. This was embodied in his decision, shortly after taking office, to ask the international consulting firm McKinsey to craft an economic strategy document for his government (Price 2010). Not only were Naidu’s reforms economically successful, they were also immensely popular and resulted in him being returned to power until 2004, despite the well-known anti-incumbency bias in Indian state elections (Uppal 2009). The 'Naidu model' of competing in elections on the basis of a programmatic platform swiftly spread to other states in India, cutting across party and ideological lines. Unlikely 'converts' have included Jyoti Basu, the long-time communist chief minister (1977– 2000) of West Bengal who began to publicly advertise his desire to attract private investment to the state, and Mayawati of the BSP, who incorporated the language of public service delivery into her public speeches and, according to several studies, actually delivered on this count (Min 2010). Additionally, a number of state chief ministers and parties have emerged that have made good governance and economic development the signature feature of their political campaigns. These include Narendra Modi, the BJP politician who has become the longest-serving chief minister in Gujarat's history by effectively championing economic modernization and development. Another leader in this mould is Nitish Kumar, the Janata Dal (United) (JDU) politician who came to power in Bihar's 2005 election on the back of a good governance agenda. While many of these parties maintain ethnic and clientelistic ties with voters, they have risen to power as a result of their ability to put together and communicate a civic programmatic agenda that involves the provision of a number of public goods. In order to fully appreciate the significance of this increase in programmaticity at the state level it is worth dwelling on the case of Bihar. Prior to Kumar's tenure, Bihar had been synonymous in the Indian imagination with clientelistic politics, economic stagnation, crime, caste conflict, widespread poverty and, above all, Lalu Prasad, the famously corrupt Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) chief minister who ruled the state from 1990–2005. It is telling that for the final few years Prasad was forced to rule through his wife, who became the nominal chief minister, after he was forced to resign during a corruption scandal. For these reasons, among others, Bihar led the so-called BIMARU (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh) list of India's 'sick' states (bimaru means 'sick' in Hindi). Yet despite the patronage resources at Prasad’s disposal, Kumar proved able to unseat the RJD by drawing together an uneasy alliance of opposition forces around a largely programmatic campaign. At his inauguration, Kumar restated his intention to pursue a good governance agenda, to improve security, to improve infrastructure, and to attract private investment to the state (The Hindu, Nov 25, 2005). The impact of Kumar's reforms was quick and tangible. In the four years leading up to 2009, the state's GDP grew annually at 10.5 per cent, exceeding the national average (The Economist, Jan 10, 2010). Crime plummeted, school enrolment rose, investment increased rapidly, and 71 infrastructure improved dramatically, all of which enabled Kumar to retain power with a landslide election victory in 2010. 'Good governance' parties and chief ministers represent a nascent programmatic revolution in India's state-level politics. Although many fail to fully include grassroots activists within the party organization, and so are similar in some ways to the cadre– programmatic model of the Congress Party, in terms of linkage and policy they are clearly programmatic. Instead of buying votes with patronage, they win support largely on the basis of economic policy, typically advocate civic policies that improve conditions for a range of groups, and implement the policies they campaign on when they gain office. The programmatic development of the party system Growing programmaticity at the party level does not always translate into fully programmatic party systems, as the case of Zambia demonstrates. Where India is concerned, one needs to first differentiate the national party system from the myriad of state-level party systems, and then to appreciate that multiple processes are playing out at each level. At the national party level, there have been contradictory trends. On the one hand, the rise of ethnic–programmatic parties has contributed to the emergence of ‘vote bank’ politics, in which parties adopt programmes and mobilization strategies oriented around existing ethnic and territorial cleavages and grievances. In this sense, increasing political competition has facilitated the representation of identity politics within the party system, as it has in much of Africa, and actually resulted in a decline in the level of party system programmaticity because the focus of inter-party competition, and of national policy debate, shifted toward the competing claims of rival groups. However, once established as national political players, ethnic–programmatic parties have significantly moderated their emphasis on identity politics in favour of widening their appeal and casting themselves as legitimate national political contenders. Over the past decade, the ‘ethnic’ component of ethnic–programmatic parties has become less prominent. As a result, competition between parties and the main issues debated around election time have begun to move away from ‘ethnic’ concerns and increasingly focus on programmatic differences. Although India is only at the very beginning of this process and the future remains uncertain, at the national level the party system appears to be undergoing a process of programmatic development. At the state level, the successful programmatic appeal of a small number of parties has proved successful, and so provided incentives for other actors to adopt the model. In states that have witnessed the rise of successful good governance parties, rival groups have begun to adopt similar strategies in response. In these cases, we see clear evidence of programmatic development within state-level party systems, with effects trickling down to the village level. In Rajasthan, for example, Krishna (2007: 147) reports a local district Congress politician telling him: 'The criterion for voting was earlier caste, now it is development. Development work done in a village has the most effect on voting.' Krishna (2007: 147) reports a similar statement by a BJP politician: 'Those individuals are gaining most influence in villages who are able to get villagers' day-to-day work done in government offices.' While each state is characterized by a unique party system, and many have yet to experience the rise of credible programmatic parties, the discourse of 'good governance' has spread across India. Even political leaders with little desire to pursue programmatic policies must rhetorically commit themselves to providing sound economic governance. Thus even where the linkage between parties 72 and voters remains unprogrammatic, political competition between parties is increasingly revolving around programmatic appeals. 3.4 Causes of and Impediments to Programmatic Politics Why has there been a transformation in the level of programmaticity within parties and party systems at both the national and local level? This section first examines possible causes of the rise of ethnic–programmatic parties at the national level, highlighting the effects of the institutional decay of the Congress Party, economic liberalization and the comparative advantage of new entrants in adopting programmatic strategies oriented around existing social cleavages. Then it discusses the role of political competition in inducing ethnic–programmatic parties to reduce their emphasis on ethnicity-based appeals. Finally, it discusses possible explanations for the emergence of programmatic 'good governance' parties at the state level, highlighting the role of economic liberalization and decentralization, leadership and agency, and demonstration effects. Explaining Variation in Programmaticity in National Party Politics The rise of ethnic–programmatic political parties such as the BJP, the BSP and a range of regional parties occurred at the expense of the Congress Party, which experienced a sustained loss of seats in the legislature during the early 1990s. Perhaps the most significant factor was the organizational decay of the Congress Party under Indira Gandhi. Facing internal and external opposition to her rule, during the 1970s Indira Gandhi severely weakened the Congress Party's internal institutions and concentrated power in her own hands. This strategy included dismantling nearly all of the Congress Party's internal democratic organs and replacing key office-holders at all levels within the party with loyalists (Kochanek 2002). While Gandhi was able to garner personal support based on her charismatic appeal, the distribution of patronage, and populist rhetoric, the process of de-institutionalization weakened the Congress Party in the long run because it left it without the well-developed local party organization needed to mobilize sustained support. Kohli (1991) notes that districts once characterized by wellorganized local Congress Party associations (according to an earlier study by Weiner in 1967) featured barely any organized Congress Party presence just two decades later. The impact of widespread organizational decay became apparent in the late 1980s, when mounting challenges to Congress across India resulted in a so-called ‘crisis of governability’ (Kohli 1991). Two other factors also played a major role in the emergence of an open competitive party system that was more conducive to programmatic development. First, economic liberalization and the decentralization of economic policymaking power weakened the Congress Party's control over central resources, undermining its purely distributive appeal to voters and local political bosses. A balance of payments economic crisis in 1991 compelled Congress Prime Minister Narasimha Rao to adopt, as part of a financing agreement with the International Monetary Fund, wide-ranging economic liberalization and decentralization reforms. This had an impact at both the national and state level. Most notably, the ‘License Raj’ system of permits was dismantled and states were given greater control over industrial policy. Chhibber and Kollman (1998; 2004) argue—in an adaptation of the logic of Duverger's Law (Palfrey 1989)—that this decentralization contributed to the fragmentation of the national political party system by reducing the incentives of regional voters and politicians to associate with the party in control of resources at the centre. Before 1991, the Congress-dominated central government could micromanage public projects, deciding where they would be located and where private investment would be approved. However, after the 1991 reforms this source of political 73 leverage was significantly reduced, particularly with regard to the control of private investment. As a result, it became less costly for voters and politicians in India's states to support alternative parties at the national and state level. Second, as the Congress Party's popularity began to fade at the turn of the 1990s, opposition parties discovered that they could successfully lure voters away with ethnicity-based programmatic appeals, something that the Congress Party's cadre programmatic model was poorly placed to do. These conditions created an opening for the rise of ethnic–programmatic parties. The reason that these new parties took on a programmatic form instead of just a clientelistic one was that programmatic appeals, with an ethnic focus, represent the comparative advantage of new entrants—which still could not compete with the Congress Party in terms of access to patronage, even after the reforms of the early 1990s. Mobilizing voters on the basis of programmatic linkages meant that new parties did not have to compete with Congress in terms of the distribution of patronage. By competing on the basis of a combination of identity and policy, the new entrants could carve out a space for themselves within the political system without first needing to access vast political funds. In her study of 'ethnic parties' in India, Chandra (2004) argues that as an umbrella-type organization the Congress Party was ill positioned to compete ideologically with specialized parties dedicated to particular social cleavages and programmatic causes. She argues, for example, that while the Congress Party had traditionally courted scheduled caste voters in Uttar Pradesh, as a party representing many constituencies and interests it was unable to make strong commitments to this group openly (for fear of alienating other constituencies). She notes that this severely constrained Congress Party politicians during elections: ‘Although in [the prominent Uttar Pradesh Congress Party leader's] speech she twice raised grievances associated with Scheduled Castes, such as untouchability, she raised these issues as a national leader concerned with the problems of one of the many groups that made up her constituency, rather than as a champion of the Scheduled Castes. Significantly, even in everyday conversations about Scheduled Castes, Kumar prefers to use the term 'they' rather than we' (Chandra 2004: 151). By contrast, BSP leaders such as Mayawati, herself a Dalit, have had few qualms aggressively championing the cause of the Scheduled Castes. This flexibility has enabled the BSP to better target and encroach upon electoral constituencies traditionally held by the Congress Party and to overcome BSP's initial relative disadvantage in terms of access to patronage. The BSP received particularly strong financial and political support from middle- and upper-class members of the scheduled castes—a growing social contingent—who were no longer content with the nominal representation provided by the Congress Party and saw the BSP as a political tool to obtain social respect and dignity (Chandra 2000). Similarly, as a party that seeks to represent both Muslim and Hindu voters the Congress Party has been committed to an official policy of secularism since independence. This rendered the party ill equipped to compete ideologically against the BJP’s hindutva platform. At the same time, the organizational weakness of the Congress Party made it vulnerable to challenges from parties capable of building an extensive grassroots organization and volunteer base, which the BJP has been able to do through its historical links with Hindu social movements and volunteer organizations such as the RSS. Thachil's (2011) account of this process is particularly striking because it documents the effectiveness of the BJP grassroots organization in winning over even poorer voters, large numbers of whom have voted for the BJP in multiple states and elections. Poor voters are thought to be an unlikely pro-BJP constituency given the party's traditional 74 popularity among upper-caste Hindu voters. But by embedding themselves within local communities and establishing a reputation for pro-poor services and activism, Thachil argues, BJP social organizers have successfully attracted even poor voters to the party. By comparison, the limited grassroots linkages of the Congress Party contributed to the once-ruling party’s inability to check the rise of new rivals. This explanation of the breakdown of Congress Party hegemony raises the question of why the BJP and BSP reduced their focus on ethnicity-based appeals, moving away from the very strategy that first elevated them to political prominence. This is best explained as the product of intense political party competition in a diverse democracy. Both the BJP and the BSP rose to prominence during the early 1990s on the basis of support from relatively narrow ethnic constituencies: in the case of the BJP, upper-caste Hindus in northern India; in the case of the BSP, Dalits in Uttar Pradesh. Although these areas represented stable ‘vote banks’ they are national minorities and so are insufficient sources of support for parties seeking national office. For example, Dalits only make up 17 per cent of the overall Indian electorate (Varshney 2000). Moreover, in an era of coalition government in which any party must attract allies in order to form a national government, parties could risk alienating all of their potential partners and so must moderate some of their appeals (Varshney 2000). As a result, the BJP and the BSP have sought to rebrand themselves as parties with a wider appeal. Interestingly, this process has occurred at the national level and also within some states. At the national level, BJP leaders have sought to move beyond upper-caste Hindu voters in Northern India to attract voters in southern and eastern India. As religion is not as important a social cleavage in these areas, this has required the BJP to focus on other more programmatic issues. Similarly, in order to attract lowercaste voters, who make up much of the Indian electorate, the BJP has been forced to advocate policies that focus on issues such as providing more effective government services. At the state level, BJP governments have stopped tolerating or tacitly encouraging violence against the Muslim minority in states where intense political competition compels the government to either seek the Muslim vote or to make alliances with parties that rely on the Muslim vote (Wilkinson 2004). Thus, political competition, in combination with India's social and geographical diversity, has contributed over time to the emergence of parties with a more inclusive and programmatic appeal. Explaining variation in programmaticity in party politics at the state level In addition to the developments discussed above, a second set of processes has facilitated programmatic development at the state level. Again, economic liberalization and the devolution of authority over economic policy promoted 'good governance' programmatic parties because it afforded state-level chief ministers the policymaking discretion to have a tangible impact on state economic performance with state-level policy. As a result, chief ministers have been able to campaign credibly on the issue of development. Moreover, the inter-state competition for private investment unleashed by liberalization has magnified the potential rewards for pursuing pro-business policies. Finally, demonstration effects played a major role in the spread of programmatic approaches, with politicians, parties and voters in states across India learning from the economic and political success of the 'Naidu model'. Economic liberalization and decentralization transformed the federal dynamics of India's economy. Prior to 1991, inter-state competition for investment was primarily a political competition for central transfers—a game in which the federal government was the decisive player. After 1991, in the words of Rudolph and Rudolph (2001: 1541), 75 ‘state chief ministers became the marquee players in India's federal market economy.’ In 1996, a group of state chief ministers even held a conference to discuss their new-found federal autonomy, adopting for the meeting the triumphant slogan ‘federalism without a centre’ (Saez 2002: 12). This development has had major implications for party politics. When state economic fortunes depended largely on transfers and project approvals from the centre, state chief ministers and political parties faced little pressure or incentives to campaign on the issue of development or to implement innovative policies within their states. This is reflected in the fact that before 1991 state-level economic policies were relatively uniform (Howes et al. 2003). After 1991, however, with the devolution of industrial policymaking authority to the states, state chief ministers became responsible for a much greater share of their own states' development (Sinha 2005). Indian states could now borrow directly from institutional lenders as well as the private sector. More importantly, with the deregulation of private investment, Indian state economies could now access significant foreign and domestic direct private investment. For the first time, good governance made sense as an election issue. Chandrababu Naidu was one of the first to demonstrate that there were major potential gains, both economic and political, to be had by adopting an aggressive good governance programme and proinvestment industrial policy. Naidu, a political entrepreneur of the highest order, worked tirelessly to attract private investment to Andhra Pradesh: ‘from Dallas to Davos, he promoted his ambitious plans to transform Andhra Pradesh from a middle rank into a top rank state’ (Rudolph and Rudolph 2001: 1542). He did this by taking advantage of the new economic context. For example, the Naidu government was the first state government in India to receive a direct sub-national loan from the World Bank, which provided over $1 billion of funding for power sector reform and industrial development (Sinha 2005: 87). This boost to government finances, which came shortly in advance of state elections in 1999, played a significant role in Naidu's continued electoral success. There is little evidence to suggest that Andhra Pradesh possesses any unique structural features which led to the emergence of this form of programmatic party politics. Rather, scholars attribute this innovation largely to Naidu’s individual skill and drive: ‘In contrast to [his predecessor's] penchant for slogans and irrepressible urge to enthral audiences, Naidu chose to give emphatic accent on the developmental agenda and navigate his party in a disciplined and workmanlike manner’ (Harshe and Srinivas 1999). The resulting boom in private investment, growth in jobs and rapid economic development proved to be a remarkable electoral elixir, dampening criticism from groups that lost political and economic influence under his administration, such as farmers (Price 2010). The precedent that it was possible to win elections on the basis of innovation and prodevelopment economic policy transformed the political landscape. Quickly, policy variation and innovation across states emerged as a result of the attempts by various leaders to follow in Naidu’s footsteps: ‘The situation by the end of the nineties was quite different [to the situation before]. Individual states took a lead in introducing reforms in different areas’ (Howes et al. 2003: 4). Rudolph and Rudolph (2001) term this change in the style of state-level politics the ‘iconization’ of Chandrababu Naidu. Price (2010) describes it as a shift in rhetorical focus from poverty to development, with ‘staples of populist politics, including subsidies of food, electricity, fertilizer, seed, etc.’ losing ground to concerns about growth and investment. The media in India, as well as NGOs, many of which receive funding from international donors, have played an important role in propagating the discourse of good governance 76 by reporting regularly on issues of political corruption (Wilkinson 2007). But the interstate spread of programmaticity was also a simple case of demonstration effects operating within a federal system. Besley and Case (1995) suggest a model of political ‘yardstick competition’ in which rational voters utilize the experiences of nearby jurisdictions to judge their own political incumbents. This logic applies just as much to programmatic party politics as other forms of evaluation. Moreover, Howes et al support the idea that state-level politicians in India learn about policies from other state-level politicians: ‘First, we would point to a strong contagion effect at work […] Movement between [the states] is fluid, news spreads and innovations seen to be successful in one state quickly becomes candidates for adoption in others, often with the intermediation of the central government, though sometimes by direct transfusion, as it were’ (2003: 4). Of course, a further factor that has facilitated the diffusion of this model is the role of national political parties themselves. If a leader from a given party successfully implements a new model in one part of the country, the party is likely to encourage other leaders to pursue a similar approach in other parts of the country. BJP state governments and chief ministers, such as Narendra Modi of Gujarat and Ashok Gehlot of Rajasthan, have developed notable reputations for good governance in multiple states, and have clearly been an example for other BJP candidates. Even if such processes of diffusion failed to operate, market forces may well have played a crucial role in propagating the 'Naidu model' in any case. States that have cultivated a business-friendly image have thrived economically since 1991, while those that have failed to do so have stagnated. Sinha (2005: 19) observes, for example, that ‘Gujarat attracted about 10.6 times as much per capita private investment as West Bengal for the period 1991–2003.’ Similar disparities exist across other pairs of states. Consistent with theories of 'market-preserving federalism' (Weingast 1995), economic competition has rewarded states that have publicly pursued business-friendly policies and sanctioned those that have failed to do so. Put another way, states that do not adopt good governance reforms are likely to go out of business, just like a failing company that fails to embrace innovation. Observes Wilkinson (2007: 133): 'State governments, in part to gain access to World Bank loans and in part to show investors and voters they are doing something about corruption, have also begun to pass freedom of information laws and introduce computerization of records that will, over time, provide fewer opportunities for politicians to extract rents'. Thus, the sub-national competition for private investment in post-liberalization India has induced parties to cultivate reputations for good governance. Yet there is also a limit to the impact of structural and learning factors, for despite liberalization in 1991 and the success of the Naidu model, many states have not yet seen the emergence of good governance parties, while programmatic parties have emerged in surprising places, such as Bihar. Wilkinson (2007), for example, writing just a few years back, expressed doubt about the possibility of reform of the clientelistic political environment in Bihar: 'In some cases, such as Bihar, where levels of economic growth are very low or negative and the middle-class out-migration is high, it is hard to see any real push for reform succeeding except in the very long term, absent an intervention from the central government' (2007: 138). Despite all of the mentioned structural impediments, Nitish Kumar has been able to reform Bihar, largely due to his personal political skill. This highlights the continued significance of political agency. The presence of committed political entrepreneurs, such as Nitish Kumar, Narendra Modi and Chandrababu Naidu, appears to be a crucial and unpredictable ingredient in the emergence of programmatic party politics. 77 3.5 Effects of Programmatic Politics Programmatic development has had an impact on policymaking at both the national and state levels. At the national level, governments have been more likely to produce efficacious public policies and govern effectively, despite an increasingly fragmented party system and the residue of identity-based parties. This is reflected in the economic reforms that have been endorsed by both the BJP and Congress, and have led to two decades of solid GDP growth. Moreover, the emergence of parties with a greater policy focus appears to have helped to prevent the political system from becoming mired in deadlock: a real concern given the continual need for coalition governments. In the current context, parties must work hard to overcome the disconnect between mass politics and elite policymaking that characterized the era of Congress Party hegemony, because failure to reflect the public mood can undermine a party’s electoral chances. Consider the BJP's disastrous 'India Shining' campaign during the 2004 general elections, which was viewed as callously over-optimistic in light of the poverty that the majority of Indians endure and contributed to a resounding electoral defeat. The focus of policy debates has also changed, and they are now more likely to feature discussion of what can be done to help some of the worst off. 'Reservations', or affirmative action policies, have become a politicized and polarizing issue, with parties such as the BSP pushing for quotas in higher education and government for disadvantaged groups and with the BJP opposing such measures. Indeed, the new-found pressure to earn votes with economic policies was an important factor behind the decision of a Congress Partyled government to implement the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act in 2005, a major policy initiative which guaranteed every rural household in India one hundred days of paid government work per year. Thus, greater programmatic competition has had a direct impact on the standard of living of ordinary Indians. The rise of parties such as the BJP and BSP has effectively reduced the historic gap between elite policymaking and mass politics, but the effect of greater programmatic competition has not all been positive. Critics argue that as a result of the growing influence of regional political parties and the increasing focus of political parties on electoral politics, the quality of legislative policymaking in India has declined. Certainly, legislative attendance and the amount of time spent drafting and debating bills has steadily fallen. This has many roots. Some critics argue that it is a product of the fact that Indian MPs increasingly come from less distinguished backgrounds, with experience mainly in the rough and tough world of local politics. It is striking that a large percentage of Indian MPs today have criminal records (Kapur and Mehta 2006). However, more research needs to be conducted in this area, as others argue that much of the legislative work in parliament has simply shifted to committees. Moreover, there are clear benefits to the changing composition of the legislature, which is now more representative of the Indian population in terms of caste and class than ever before (Shankar and Rodrigues 2011). At the state level, meanwhile, programmatic parties have had mostly positive effects on policy outcomes. Both Bihar and Gujarat, a low- and high-income state, respectively, have experienced dramatic gains in economic productivity following the election of programmatic parties. State GDP visibly took off in Gujarat shortly following the election of Narendra Modi and the BJP in 2001 and in Bihar shortly following the election of Nitish Kumar and the JDU in 2005. At the same time, state institutions have been tremendously strengthened. Both Kumar and Modi are credited with cracking down on corruption and overhauling inefficient bureaucracies. In Bihar, Kumar has strengthened the police, the courts and the schools considerably, and has also stepped up spending on 78 infrastructure, most notably the road system (Chand 2010). For his part, Modi has been noted for creating an extremely transparent, efficient and business- and investorfriendly bureaucracy (Sinha 2005). However, there are also variations between states, which reflect the disposition of the individuals and parties in power. Kumar's most remarkable achievement is perhaps the restoration of law and order to Bihar, previously one of India's most violent and crimeridden states (Economist 2010a). Modi, by contrast, has a less positive record. A prominent BJP leader, he has been accused of knowingly failing to stop anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat in 2002 which resulted in the death of over 1,000 Muslims (Hindu 2011). Here the tension between the different components of the BJP’s platform is laid bare— although, as noted above, the party has moved away from this sort of behaviour as it has consolidated as an ethnic–programmatic party. 3.6 Lessons and Policy Implications from the Indian Case India offers several 'portable' lessons with regard to programmatic party politics. First, party programmaticity is a complicated quality and can emerge through a number of different processes. The evolution of the BJP from an ethnic party to an ethnic– programmatic party, for instance, involved a period in which the party’s Hindu nationalist programme led to violence against Muslims. The BJP represents a coherent and stable set of ideological policies, but many of these are not normatively desirable. Even if the BJP continues to abandon the more extreme aspects of its position and consolidate as an ethnic–programmatic party, its linkages to voters and policies are likely to be less conducive to national unity and political stability than that of a civic– programmatic party. It is therefore vital that democracy promotion actors take a critical attitude with regard to what forms of programmaticity they seek to promote. Political competition in a diverse democracy can induce political parties to moderate their emphasis on ethnic cleavages. Both the BJP and the BSP have significantly moderated their identity politics over time in order to widen the scope of their electoral appeal in a competitive political environment. The reduction of barriers to national political competition is therefore important to the long-term promotion of programmaticity. This means that the promotion of campaign finance reform, the modernization of electoral technology, the deployment of election observers, and other instruments to induce or ensure robust political competition are important strategies that donors and others can use to drive programmatic development. Economic reforms can have a major impact upon programmaticity by altering the resources and opportunity sets of political parties and political party leaders. In the Indian case, economic liberalization and decentralization contributed to the decline of clientelistic parties and the emergence of new parties in a programmatic mould. Given this, it is important to keep in mind the relationship between economic and political reform. Most obviously, anti-corruption campaigns and programmes to promote fiscal accountability and transparency should be supported because they are likely to indirectly promote programmatic development in the long run. At the same time, the devolution of key policymaking responsibilities to the sub-national level may encourage sub-national politicians and parties to adopt programmatic strategies and to compete to demonstrate their good governance credentials. By supporting programmes of devolution—where conditions on the ground render them 79 feasible—international actors such as IDEA can help to create the conditions under which parties and leaders have an incentive to adopt programmatic positions. Demonstration effects can be crucial in the spread of programmatic party politics. The success of Chandrababu Naidu and the TDP established a precedent that led to the adoption of programmatic strategies in a number of other states, notably Bihar and Gujarat. The rapid spread of ‘good governance’ models demonstrates the great importance of education, communication and training. Organizing events in which such lessons can be more easily communicated to aspiring political leaders is therefore a very feasible way in which the democracy promotion community can advance the position of programmatic parties. This may be implemented though the facilitation of dialogue between parties across states, the facilitation of dialogue between parties and civil society organizations, and the provision of policy advice and consulting services. 3.7 Bibliography Basu, Amrita (2012). ‘The BJP’ in Atul Kohli and Prerna Singh (ed.) Handbook of Indian Politics. Routledge pp. 120–129. Besley, Timothy and Anne Case (1995). ‘Incumbent Behavior: Vote-seeking, Tax-Setting, and Yardstick Competition’ in American Economic Review Vol. 85, No. 1 (March). Bose, Sugata and Ayesha Jalal (2004). Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy. 2nd edition. Oxford: OUP. Brass, Paul (1994). The Politics of India Since Independence. 2nd edition. Cambridge: CUP. Chand, Vikram (2010). Public Service Delivery in India: Understanding the Reform Process. Oxford: OUP. Chandra, Kanchan (February 2000). ‘The Transformation of Ethnic Politics in India: The Decline of Congress and the Rise of the Bahujan Samaj Party in Hoshiarpur’ in The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 59, No. 1. Chandra, Kanchan (2004). Why Ethnic Parties Succeed. Cambridge: CUP. Chhibber, Pradeep and Ken Kollman (June, 1998). ‘Party Aggregation and the Number of Parties in India and the United States’ in American Political Science Review, vol. 92, No. 2. Chhibber, Pradeep and Ken Kollman (2004). The Formation of National Party Systems. Princeton: PUP. The Economist. ‘A Triumph in Bihar’ November 25, 2010a. The Economist. ‘On the Move: Bihar's Remarkable Recovery’ January 28, 2010b. Guha, Ramachandra (2007). India After Gandhi. New Delhi: Picador. Harshe, Rajen and C. Srinivas (1999). ‘Vote for Development: How Sustainable?’ in Economic and Political Weekly Vol. 34, No. 44: 3103–3105. The Hindu (November 25, 2005). ‘Nitish Promises “good governance”’. The Hindu (April 22, 2011). ‘Gujarat Police Officer Implicates Modi in Riots’. Hasan, Zoya (2002). ‘Representation and Redistribution: The New Lower Caste Politics of North India’ in Zoya Hasan (ed.) Parties and Party Politics in India, Oxford: OUP. Howes, Stephen, Ashok Lahiri and Nicholas Stern (2003). State-level Reforms in India: Towards More Effective Government. Macmillan: New Delhi. Jaffrelot, Christophe (1998). ‘The Bahujan Samaj Party in North India: No Longer Just a Dalit Party?’ in Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, VOL. XVIII NO. 1 Jaffrelot, Christophe (2007). Hindu Nationalism: A Reader (Permanent Black). 80 Jaffrelot, Christophe (2007a). ‘Caste and the Rise of Marginalized Groups’ in Sumit Ganguly, Larry Diamond and Marc Plattner (eds.) The State of India's Democracy. Baltimore: JHU Press. Kapur, Devesh and Pratap Mehta (2006). The Indian Parliament as an Institution of Accountability. Democracy, Governance and Human Rights Program Paper Number 23, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. Kochanek, Stanley (2002). ‘Mrs. Gandhi's Pyramid’ in Zoya Hasan (ed.) Parties and Party Politics in India, Oxford: OUP. Kohli, Atul (1991). Democracy and Discontent: India's Growing Crisis of Governability. Cambridge: CUP. Kohli, Atul (2001). ‘Introduction’ in The Success of India's Democracy. Cambridge: CUP. Kohli, Atul (2006). ‘Politics of Economic Growth in India’, Economic and Political Weekly, April 8: 1361–70. Kothari, Rajni (Dec., 1964). ‘The Congress 'System' in India’ in Asian Survey, Vol. 4, No. 12. Krishna, Anirudh (2007). ‘Politics in the Middle: Mediating Relationships between the Citizens and the State in Rural North India’ in Patrons, Clients and Policies. eds. Herbert Kitschelt and Steven Wilkinson, Cambridge: CUP. Manor, James (2010). ‘Beyond clientelism: Digvijay Singh’s participatory, pro-poor strategy in Madhya Pradesh’, in Pamela Price and Arild Engelsen Ruud, eds. Power and Influence in India: Bosses, Lords, and Captains, Delhi: Routledge, pp. 193–213. Min, Brian (2010). ‘Distributing Power: Electrifying the Poor in India’. Working Paper: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~brianmin/Min_UP_20101019.pdf Mitra, Subrata (2011). Politics in India: Structure, Process and Policy. Routledge. The New York Times. ‘Turnaround of India State Could Serve as Model’, 10April, 2010. Palshikar, Suhas (2012). ‘Regional and Caste Parties‘ in Atul Kohli and Prerna Singh (eds.) Handbook of Indian Politics. Routledge. Panagariya, Arvind (2004). ‘India in the 1980s and 1990s: A Triumph of Reforms’ in IMF Working Paper Series WP/04/43. Price, Pamela Gwynne (2010). ‘Development, Drought and Campaign Rhetoric in South India: Chandrababu Naidu and the Telugu Desam Party, 2003–2004’ in Arild Engelsen Ruud & Pamela Gwynne Price (eds.), Power and Influence in India: Bosses, Lords and Captains. Routledge. Palfrey, Thomas (1989). ‘A Mathematical Proof of Duverger's Law’ in Peter Ordeshook (ed.) Models of Strategic Choice in Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan. Rudolph, Lloyd and Susan Rudolph (2001). ‘Iconisation of Chandrababu: Sharing Sovereignty in India’s Federal Market Economy’ in EPW 5 May 2001: 1541–52 Saez, Lawrence (2002). Federalism Without a Center. Sage: New Delhi. Shankar, B.L. and Valerian Rodrigues (2011). The Indian Parliament. New Delhi: OUP. Stokes, Susan (2007). ‘Political Clientelism’ in Carles Boix and Susan Stokes (eds.) Handbook of Comparative Politics. Oxford: OUP. Sinha, Aseema (2005). The Regional Roots of Developmental Politics in India. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Thachil, Tariq (July 2011). ‘Embedded Mobilization: Non-state Service Provision as Electoral Strategy in India’ in World Politics Vol. 63, No. 3. Tripathi, Ashis (March 22, 2007). ‘Bahujan Samaj to Brahmin Samaj’ in The Times of India, Lucknow, India edition. Uppal, Yogesh (2009). ‘The Disadvantaged Incumbents: Estimating Incumbency Effects in Indian State Legislatures’ in Public Choice, 138(1), 9–27. Varshney, Ashutosh (Feb., 2000). ‘Is India Becoming More Democratic?’ in The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 59, No. 1. Varshney, Ashutosh (March/April 2007). ‘India's Democratic Challenge’ in Foreign Affairs, Vol. 86, No. 2. Weiner, Myron (1967). Party Building in a New Nation: The Indian National Congress. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 81 Weingast, Barry (1995). ‘The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development’ in Journal of Law, Economics and Organization Vol. 11, No. 1. Wilkinson, Steven (2004). Votes and Violence. Cambridge: CUP. Wilkinson, Steven (2007). ‘Explaining Changing Patterns of Party–Voter Linkages in India’ in Patrons, Clients and Policies, eds. Herbert Kitschelt and Steven Wilkinson, Cambridge: CUP. World Bank (2005). Fiscal Reforms in India: Progress and Prospects. Macmillan: India. 82

![612:3-5-29. Program Standards [AMENDED]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007495491_1-6b02ab1f993713111546a2a9b18b2949-300x300.png)