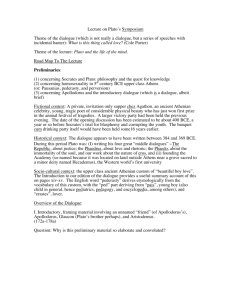

A Visual Introduction to the Musical Structure of Plato's Symposium

advertisement

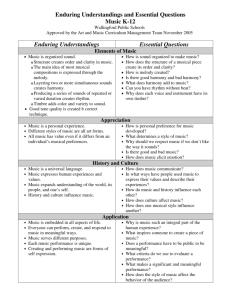

A Visual Introduction to the Musical Structure of Plato’s Symposium (For Reference Only, Not Publication)∗ May 15, 2008 Abstract The musical structure of Plato’s Symposium is illustrated with a series of pictures, diagrams, and graphs. Various, easily measurable kinds of evidence for the existence of a musical scale embedded in the dialogue are presented visually, so that patterns that stretch over the course of the dialogue can be surveyed at a glance. Since a picture is worth a thousand words, the following series of pictures and diagrams illustrates the arguments of a companion essay,1 and is an expanded version of some slides prepared for a talk on its central findings. The diagrams aim to convey the sometimes subtle evidence of the essay in a concise and readily accessible way. The essay laid out the textual and historical evidence for the surprising claim that Plato’s dialogues were organised around a musical scale, and that certain symbols and keywords were introduced into his narratives to mark out the regular intervals of that scale. Plato’s Symposium is particularly suitable for introducing and displaying these musical structures. The series of speeches, from Phaedrus to Alcibiades, breaks the text into discrete and objectively distinguished parts whose lengths reveal further evidence for the underlying musical scale. To say that Plato organised his dialogue around a twelve-part scale is, in the first place, to say no more than that he made a twelve-part outline of this text and allocated the same number of lines to each part. The essay reviewed evidence that the lines in classical texts were counted in ways perhaps similar to the way we count words or pages. As before, this essay concentrates on exhibiting the evidence and avoids references to later theories of allegory and literary symbolism. It is important to make a clean case for the existence of the musical organisation before entering into debates about its ideology. It is clear, however, that the notion of forms beneath appearances is a thoroughly Platonic idea, and that the notion of an imperceptible musical and mathematical structure comports well with the kind of Pythagoreanism on display in the Timaeus. ∗ Draft. Comments and criticism but not quotes are welcome. Prepared for blind review. I would like to thank .... I would like to acknowledge the support of ... This is an expanded version of illustrations prepared for a seminar at the University of .... 1 Figure 1: Pythagoras’s Slate in the Foreground of Raphael’s School of Athens (left, detail) Bears a Diagram of the Pythagorean, Six-to-Twelve Musical Scale (right) 1 The Twelve-Note Scale The historical background of a scale with twelve, regularly spaced notes was surveyed in the companion essay. The diagram above illustrates the Pythagorean association between the principle notes in a musical scale and the integers up to twelve. This was known to the Renaissance through works like Ficino’s translation of Theon’s On the Mathematics Useful for Understanding Plato. [In this draft, some large gaps have been left at the bottom of pages.] 2 12 End of the dialogue. 11 10 Octave, a 6:12 or 1:2 ratio 9 8 7 6 At the centre of the Symposium, the climax of Agathon’s speech: lyrical praise of Eros, a procession, loud approval; Socrates begins to speak. 5 4 3 2 1 Beginning of the dialogue. Figure 2: The Symposium is Divided into Twelve Parts, Corresponding to a TwelveNote Musical Scale As the above figure shows, the scale divides the text of the dialogues into twelve equal parts, with Note 1 near the beginning of the text. The centre of the Symposium is emphatically marked. In a dialogue devoted to love, the conclusion of Agathon’s speech with its rousing rhetorical fireworks in praise of Eros flanks one side of the centre. Socrates, the philosophical hero of the dialogue, begins to speak at the centre. 3 cb bc bc 6 Agathon’s speech fills the fifth twelfth. 5 Aristophanes’ speech fills the fourth twelfth. 4 Eryximachus’ speech fills the third twelfth. 3 Pausanias’ speech fills the second twelfth. 2 cb bc bc Figure 3: Lengths of Speeches, Measured End to End The lengths of the speeches in the first half of the Symposium strikingly show how the underlying musical scale has been used to organise the dialogue. The figure shows simple and objective measurements of the interval from the end of one speech to the end of the following speech. The speeches are surrounded by comments, repartee, or short cross-examinations, and this figure treats all such banter as part of the following speech. A later section explores the fine structure of this banter, and shows that it too has lengths determined by the underlying musical scale. The location of each note is marked by a passage with certain key, symbolic terms (see below). A speech, therefore, tends to stop just before or just after a note, depending upon whether it contains the marking passage or not. The speeches after the centre of the dialogue have lengths longer than one-twelfth (see below). The lengths of speeches can be easily and objectively measured, and therefore are the focus here. A careful reading of the dialogues will show that many of their features, from narrative and argument to key symbols and definitions, have been organised around the musical scale. 2 Harmonic and Disharmonic Notes Measurements of length provide some evidence that Plato was counting lines when composing his dialogues, but do not in themselves show that the twelve-part structure is a musical scale. Another form of evidence shows a consistent connection between the stichometric organisation and a musical scale. 4 Figure 4: Two Strings Struck to Test Harmony Some pairs of notes sound better together than other pairs. Two notes an octave apart, for example, ‘harmonise’ with each other. The Pythagoreans noticed that pairs of notes which sound well together are produced by pairs of strings whose lengths stand in simple, whole-number ratios like one-to-two or three-to-four. A pair of notes an octave apart, for example, are produced by strings whose lengths have a one-to-two ratio. The Pythagoreans went further and found ways to rank notes according to whether they were more or less harmonious when paired with some fixed note. The series of notes on a twelve-note scale can all be separated into two classes as follows: Harmonious Notes: 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9 Disharmonious Notes: 1, 5, 7, 10, 11 Here, the twelfth note is used as a fixed standard of comparison, and each note is played together with this standard. The successive pairs – 1 and 12, 2 and 12, and so on – are ranked according to whether they are more or less harmonious. 5 12 11 10 The top of Diotima’s ladder at note: her vision of the Form of the One 9 Diotima describes the Form of Beauty in itself at the note 8 7 Agathon’s peroration: praise of Eros, procession, loud approval, Socrates 6 5 Aristophanes begins with praise of Eros: philanthropic, healing powers 4 Pausanias’s concluding praise of heavenly Eros: leads to virtue 3 Pausanias: all gods must be praised, heavenly vs. common Eros 2 1 Harmonic Notes Figure 5: Harmonious Passages at Harmonious Notes The twelve-note musical scale and the theory of relative harmony provide a key to the structure of Plato’s dialogues. Plato’s dialogues are full of value-judgements: philosophy is valued over other pursuits, the soul over the body, truth over falsity, dialectics over mere disputatiousness, and so on. As a general tendency, the locations of harmonious notes contain passages with positively valued concepts. This figure shows that important concepts or passages within the dialogue are carefully lodged at the locations of notes (at 1/12, 2/12, etc.), and that more ‘harmonious’ concepts are located at more harmonious notes. The coloured bars show the locations of the harmonious notes: the longer the bar, the more harmonious the note. The top of Diotima’s Ladder where the Form of the One is described is a philosophically key passage in the Symposium. It is located at a note: the harmonious ninth note. The harmonious notes are marked either by descriptions of the forms, perhaps the most highly valued concepts in Platonism, or by praise of the god of love. 6 12 Alcibiades’ shame and anguish after being rejected and dishonoured by Socrates Alcibiades calls Socrates an hubristees; compares him to an ugly, pipe-playing Satyr 11 10 9 8 Diotima’s elenchus of the young Socrates: Eros is not a god. 7 6 Aristophanes asks not to be mocked: Socrates’ fear and aporia before speaking. 5 4 3 2 Hangovers from the previous night; Eryximachus condemns drunkenness. 1 Disharmonic Notes Figure 6: Disharmonious Passages at Disharmonic Notes There is a dramatic contrast between the passages at the locations of the harmonic and disharmonic notes. Instead of the forms or praise of Eros, the disharmonic notes are marked by shame, insults, contradictions, mockery, and hangovers. As will be discussed below, the positive concepts at harmonic notes are part of passages in which language is used to promote social harmony: agreements, praise, etc. The negative concepts at disharmonic notes are, in contrast, associated with language which produces social disharmony. These instances of verbal or social harmony and disharmony mark the notes. 7 12 Alcibiades: rejected, war 11 Alcibiades: Satyr, seduction 10 9 Diotima: Ladder, Form of One 8 Diotima: Form of Beauty Diotima: elenchus, myth of sex and seduction among gods 7 Socrates: the nature of eros Agathon’s peroration 6 Agathon: arty rhetoric 5 Phaedrus: myths, shame ethics 4 Aristophanes: myth of true love 3 Eryximachus: erotic harmony 2 Puasanias: love and pederasty 1 Disharmonic Intervals Harmonic Intervals Figure 7: Regions near Harmonic Notes have Positive Themes, and Regions near Disharmonic Notes have Negative Themes The over-arching structures of Plato’s dialogues have been much debated. They sometimes seem meandering or disjointed. They do not follow common shapes like ‘development, crisis, resolution,’ nor build slowly to a concluding climax. Remarkably, however, the sequence of topics in his dialogues does conform to this Pythagorean theory of relative harmony. Careful study of the dialogues shows that a region in the musical scale near a harmonic note is dominated by more positive concepts and, similarly, a region near a disharmonic note is more negative. More specifically, the region stretching from a little before a note in the scale almost to the next note generally shares the earlier note’s degree of harmony. (For example, Socrates’ elenchus of Agathon occurs as the disharmonic, seventh note is approached.) This is strikingly illustrated by the Symposium. The speech of the notorious Alcibiades lies in the most disharmonic region of the dialogue. Similarly, Agathon’s suspect speech, which Socrates criticised for lacking truth, lies in the next most disharmonic region. On the other hand, the philosophical peaks of Diotima’s speech and the marvelous mirth of Aristophanes’ speech occupy harmonic regions. 8 12 Tartarus, River Styx 11 Geography of the Underworld 10 9 Forms, soul is immortal 8 Form of Beauty, hypotheses Disharmony, soul is not a harmony 7 Socrates’ equanimity 6 Vices, evil, doubt 5 Suicide, body 4 Proof of immortality, forms 3 Recollection, forms 2 Death as liberation, virtues 1 Disharmonic Intervals Harmonic Intervals Figure 8: In the Phaedo, Regions near Harmonic Notes have Positive Themes, and Regions near Disharmonic Notes have Negative Themes Study of the other dialogues confirms this correlation between positive or negative concepts and the series of regions between the notes. In the Phaedo, the regions after the eighth and ninth notes, as in the Symposium, describe the forms. On the other hand, the region around the last two disharmonic notes describes Hell and the filthy River Styx. The argument that the soul is not a harmony, which explicitly mentions ‘disharmony,’ follows the disharmonic seventh note. Similarly, in the Symposium, Eryximachus’ discussion of erotic ‘harmony’ followed a harmonic note. This pattern is remarkably consistent across the dialogues. Although there may be some uncertainty about the precise locations of the notes, studying the ‘harmonic’ character of these longer passages in the regions between notes does not depend upon any precise measurement of locations within the text. 9 0.618 12 12 12 11 11 11 10 10 10 9 9 9 8 8 8 7 7 7 6 6 6 5 5 5 4 4 4 3 3 3 2 2 2 1 1 1 Rep. Symp. Parm. Figure 9: Passages Alluding to the Golden Mean One way of confirming the relevance of the Pythagorean theory of harmony is to show that other Pythagorean concepts appear in the Symposium. The Golden Mean, a mathematically significant number approximately equal to 0.618, has been a theme in later Pythagoreanism as well as among cranks and numerologists up to the present day. Several scholars have interpreted the Divided Line passage in the Republic as an allusion to the Golden Mean. Remarkably, this passages begins 61.7% of the way through that dialogue. Even more remarkably, the other dialogues also seem to allude to the Golden Mean at the same point. In the Symposium, Socrates asserts that neither the ignorant nor the wise are philosophers, since both are perhaps content with their condition. In contrast, he says at 61.6% of the way through the text that the philosopher is at the mean or in the middle between ignorance and wisdom. This associates the notion of a philosophical or ethical mean with the mathematical notion of a mean, just as explicitly occurs in Aristotle. At the parallel location in the Parmenides, a passage echoes Euclid’s geometric definition of the Golden Mean. This is quite strong evidence for the underlying musical scale. On the one hand, a number of scholars have argued for the possible or probable link between the Divided Line and the Golden Mean. It is surprising to find the passage in the Republic near 61.7%. On the other hand, the passages at similar locations in other dialogues consistently refer to mathematical or ethical means. 10 Figure 10: A Classical Symposium (from the Tomb of the Diver, Paestum, c. 470 B.C.E.) 3 The Quarternote Structure This section introduces a further, musical concept and shows how it gives the speeches a more fine-grained structure. One theme in the debates over musical theory in Plato’s time and long afterwards was the question of whether there were ‘quarternotes’ or smaller intervals between the usual notes of a musical scale.2 The concept of a quarternote was discussed by Plato, Aristotle, Aristoxenus, and others, and was sometimes understood to be the smallest unit by which musical scales should be measured. The intervals between the twelve ‘whole’ notes in the Symposium are further organised around a structure of quarternotes. That is, shifts between speakers, major turns in arguments, and central concepts are often lodged one, two, or three fourths of the way between the whole notes. The internal organisation of the speeches, both shorter and longer, in this dialogue reveals this further, fine-grained structure. 11 b b b 1q Note 9 3q 2q 1q Note 8 Socrates’ Speech, Length: 3 3q 2q 1q b b b Note 6 Note 7 3q 3q Agathon’s Speech, Length: 3/4 2q 1q 2q 1q Banter, Length: 1/4 Note 5 Banter, Length: 1/4 Note 6 b b b b b b Figure 11: Some Speeches Stop and Start at Quarter-Intervals This figure shows two sorts of simple evidence for the role of quarternotes. The lengths of Agathon’s speech is a multiple of the quarter-interval, and the lengths of the banter before the two speeches extend through one-quarter interval. This suggests that the distance of one-quarter of the length between successive whole notes plays a role in the organisation of the Symposium. Moreover, these speeches as well as the banter and repartee before them stop and start at quarternotes. Thus both the lengths and the locations are evidence for the role of quarternotes. 12 b b b Note 9 Republic 3q ... the Pythagoreans ... [measure] audible concords and sounds one against each other ... [Others] talk of ‘groups of quarter-tones’ ... [each is] a note in between, giving the smallest possible interval, which ought to be taken as the unit of measurement. (Cornford’s translation: 530d8 – 531a7) 2q 1q Note 8 b b b b b b Note 5 Symposium 3q Aristophanes makes Zeus say: ‘And if they still appear licentious and will not behave quietly, then I will cut them in two all over again [i.e., into quarters], so that they will go about hopping on one leg [instead of four]. (190d4-6) 2q 1q Note 4 b b b Figure 12: Passages Alluding to Quarters at the Locations of Quarternotes The figure above gives two examples of a kind of punning reference in Plato’s dialogues to the musical structure. The Republic refers to quarternotes at the location of a quarternote on its embedded scale.3 The Symposium refers to cutting into quarters at the location a quarternote. This limited evidence cannot in itself be convincing, but such puns are common in the dialogues. For example, the dialogues sometimes refer to three near the third note, or four near the fourth note, and so on. The passages in the figure show at least that Plato discussed smaller intervals between the main notes in a musical scale and add another kind of evidence, however limited here, for the role of quarternotes. Their brevity makes puns hard to interpret in rigourous ways. The scholarship on 13 puns in classical or later literatures generally depends upon an argument from coherence. That is, by examining many examples and drawing on explicit discussions of punning, etymology, and allegory in related writings, secure interpretation of puns in individual cases can be reached. During the last generation, a substantial literature on puns in Homer, Aristophanes, Ovid, and Virgil has clarified the various motivations for punning in classical literature.4 Sedley, in particular has argued that Plato’s Cratylus should be read as evidence for a serious interest on Plato’s part in etymological puns. The following figure introduces yet another kind of evidence for quarternotes and requires some introduction. Plato uses a subtle scheme for marking the locations of musical notes at regular whole and quarter intervals in the Symposium. The theory of his marking scheme is given in the Symposium itself. Examining first the theory and then the passages marking the opening quarternotes in the dialogue will reveal much about Plato’s symbolic techniques. The Symposium contains, in Eryximachus’ speech, an explicit theory of the nature of music (187a1 ff.). It involves two combinations of opposites: of fast and slow, and of high and low. We might call these ‘tempo’ and ‘pitch,’ but for Plato the first is ‘rhythm’ and the second is ‘harmony’ or ‘consonance’ (symphōnia). Plato succinctly summarised this view of music in the Laws: ... rhythm is the name for the order of the motion and harmony is the name for the order of the sound. (664e8-a2) An uptempo or fast rhythm, for example, is one in which the mixture of ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ is dominated by ‘fast.’ Both rhythm and harmony are thus types of blending or ‘agreement’ between opposites. Music establishes such agreements, according to Eryximachus, by implanting eros and homonoia, or love and like-mindedness. Eros is therefore a mediating force which reconciles disagreeing elements, and music is a science: the ‘erotics’ of rhythm and harmony, or of motion and sound.5 This theory of music is the key to the symbolism that Plato uses to mark the notes in the Symposium.6 Careful examination shows that there is a definite similarity between passages lodged at the locations of the notes through the musical scale. The figure summarises the first four such passages in the dialogue, where the pattern is rather heavy-handedly established. 14 b b b 3q Motion: Socrates’ starts again, arrives at Agathon’s (175c4). Wise/Unwise: Socrates’ ‘wisdom’ requested by dramatist Agathon (c8). Invite/Agree/Harmony: Agathon asks, Socrates agrees to sit together (d3). Motion Stops: Socrates sits, motion ceases again (d3). 2q Motion: jokes about going to Agathon’s, departure (174c7, d4). Wise/Unwise: ‘wise’/phaulos, Socrates and Aristodemus (c7,d2). Invite/Agree/Harmony: invitation, agree to attend the dinner (d3). Motion Stops: Socrates stops on the road (d5-6). 1q Motion: walking along the road to the city (173b9). Wise/Unwise: ‘philosophy’ vs. worldly pursuits (c3-5 ff.). Invite/Agree/Harmony: agrees to recount the speeches (c2). Motion Stops: interlocutor is really ‘doing nothing’ (d1). 0 Motion: Apollodorus was going to the city (172a2). Wise/Unwise: young philosopher, ignorant inquirer. (173c2-5, b8-c2) Invite/Agree/Harmony: he is asked to stop and does (a4). Motion Stops: Apollodorus stops (a5). Figure 13: Similar Passages Mark the First Four Quarternotes: Each Contains the Elements of Music, Motion and Harmony These four passages share a consistent set of features. At each note, there are words indicating some sort of physical motion like walking. Each passage also concludes with the cessation of motion. Moreover, there is at each note some sort of agreement – either assent to a request or acceptance of an invitation – between a student of philosophy and someone else. Like a musician who rather emphatically begins with ‘ONE, two, three, four,’ the Symposium marks the interval between its initial quarternotes with a rhythmically repeated pattern of passages.7 In short, there is a kind of rhythm (motion) and a kind of harmony (agreement) at the location of each note. The concepts, or perhaps the forms, of music mark the locations of the notes. A Platonist might conclude that, since the forms are the reality beneath appearances, there is real music at each note. 15 Figure 14: A Tabulation of the Occurrence of Music-Related Words in the Republic, Showing the Second and Third Musical Notes and Intervening Quarternotes This figure shows the results a novel investigation which, once understood, provides powerful evidence for the existence of quarternote structure in the Republic. In that dialogue, the locations of the whole notes are marked by clusters of musical and music-related words (like lyre, chord, string, tone, harmony, noise, etc.). Careful study of the passages at the whole notes produced a list of these words. In an effort to show that these clusters occurred only at the locations of the whole notes, I proceeded mechanically through the entire dialogue recording and tabulating the locations of these key, musical terms on my list. This led to a table giving the number of occurrences of these words in each Stephanus page. I was surprised to see smaller clusters of the key terms at three regular intervals between each pair of successive whole notes. This was the first evidence for the existence of the quarternotes. This chart shows the structure between the second and third whole notes. There is a larger number of musical terms spread over a larger number of Stephanus pages at the whole notes, and smaller peaks at the quarternotes, but the histogram beautifully shows the quarternote structure. Tabulating the occurrences of a random list of words in the Republic would not have produced a regular structure. Thus my list of key terms and the graph reinforce each other, and constitute a strong, visual form of evidence for the presence of quarternotes. 16 4 Summary of the Evidence The preceding illustrations aimed to assemble a range of independent, yet mutually reinforcing lines of evidence for the musical scale in the Symposium. Simple evidence for the twelve-note scale: • four speeches early in the Symposium are each about one-twelfth long • these four speeches each begin and end near a whole note • Socrates’ speech is three-twelfths of the entire text • highlights of Diotima’s speech, the form of Beauty and the form of the One, occur at successive notes, and thus are separated by one-twelfth • the rhetorical climax of the Symposium is located at its centre Evidence from the Pythagorean theory of relative harmony: • harmonious concepts are lodged at harmonious notes, e.g., the top of Diotima’s ladder is reached at the ninth note • disharmonious concepts are lodged at disharmonious notes, e.g., the River Styx at the eleventh note of the Phaedo • regions after harmonious notes are filled by speeches about the forms or with praise of Eros • regions after disharmonious notes are filled by speeches about shame, insults, or arty rhetoric • a similar pattern of regions occurs in the Phaedo (and other dialogues), showing that this gives the general structure of Plato’s dialogues • the musical structure was tied to another Pythagorean concept, the Golden Mean Evidence for quarternotes between the twelve whole notes: • the lengths of Agathon’s speech and of some banter are multiples of the quarterinterval • the speeches of Agathon and Socrates each begin at a quarternote • an explicit discussion in the Republic of quarternotes is lodged at the location of a quarternote • a reference to quartering at the location of a quarternote in the Symposium • the four passages marking the Symposium’s first four quarternotes are similar and contain references to motion and agreement, i.e., to the elements of music • a tabulation of the music-related terms in the Republic clearly shows a regular series of peaks at the locations of whole and quarternotes. 17 5 Appendix: Locations of the Musical Notes As discussed in the companion essay, the measured locations of the musical notes on the Symposium’s musical scale are surprisingly accurate, despite the changes the text may have undergone during its transmission. The Stephanus pages have significantly variable lengths but, in the Symposium and not generally in other dialogues, the interval between quarternotes is coincidentally about one Stephanus page. Note 0: Note 1: Note 2: Note 3: Note 4: Note 5: Note 6: Note 7: Note 8: Note 9: Note 10: Note 11: Note 12: 172a1, 176c5, 180e3, 185b6, 189d5, 193d8, 198a8, 202c7, 206e1, 211b4, 215c2, 219d6, 223d12 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 1q: 173c3, 177c6, 182a3, 186c2, 190d6, 194e5, 199b4, 203c7, 207e5, 212b8, 216c5, 220d6, 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 2q: 174c6, 178d2, 183a7, 187c8, 191d7, 195e8, 200b11, 204d4, 209a5, 213c3, 217c7, 221d8, 18 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 3q: 175c5, 179d6, 184b1, 188d1, 192e1, 197a3, 201c4, 205d9, 210b1, 214c1, 218d1, 222e7, Notes 1. Plato’s Forms, Pythagorean Mathematics, and Stichometry is under review. 2. The difference between a musical fifth and a third gave the basic interval of a tone (between note 8 and 9). A quarternote would be one-fourth of this distance. The concept and terminology for these smaller notes varied significantly during antiquity. See West, Barker, Huffman, etc. 3. This passage has been much debated. I have used Cornford’s translation here. Adam’s commentary discusses this passage. 4. See the companion essay for references. 5. This passage (187c4-8) lies at the second quarternote after note 3. 6. Each of Plato’s dialogues uses a different general scheme to mark its notes, but the scheme is usually explicitly (and obliquely) discussed in the dialogue. That is, each dialogue gives the theory needed for the interpretation of its symbolic scheme. 7. From the first whole note until the advent of Alcibiades, the musical notes are marked with various species of homologia but not with explicit motion (Alcibiades appropriately reintroduces motion and disturbance). The narrator, however, is walking to town while reciting the speeches. Thus, once the motion or tempo is established in the opening quarternotes, it perhaps recedes into the background. 19