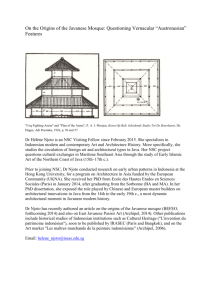

Ahmad Muttaqin - School of Social Sciences

advertisement