The origin and evolution of management accounting

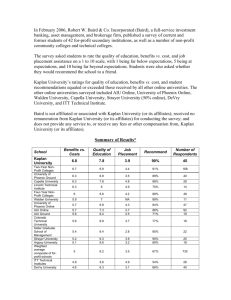

advertisement