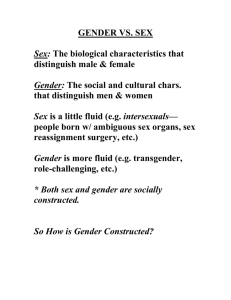

The role of social socialization tactics in the relationship between

advertisement