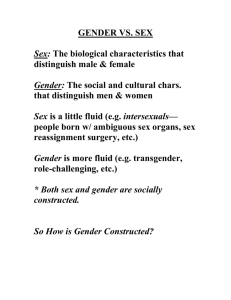

a re-examination of the impact of socialization practices

advertisement