Fisheries Leader Resource Guide

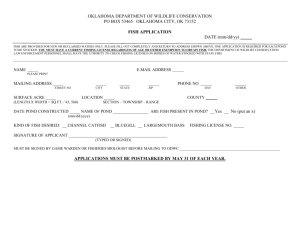

advertisement