Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA)

advertisement

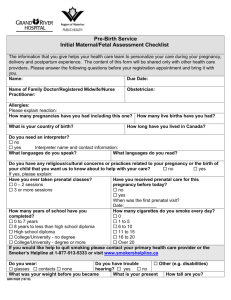

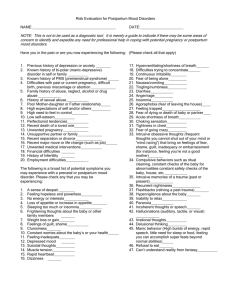

Provider’s Guide Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment Deana Midmer, BScN, EdD, FACCE Faculty of Medicine Department of Family and Community Medicine University of Toronto Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment Provider’s Guide 3rd Edition Deana Midmer, BScN, EdD, FACCE Faculty of Medicine Department of Family and Community Medicine University of Toronto 3rd Edition September, 2005 Copyright © 2005 by The ALPHA Group Department of Family & Community Medicine Faculty of Medicine University of Toronto For information on this reference guide, the development of the ALPHA Form, and the companion provider-training video The ALPHA Form: Assessing Antenatal Psychosocial Health Direct inquiries to: The ALPHA Group Department of Family & Community Medicine 263 McCaul Street, 5th Floor Toronto, M5T 1W7, ON, Canada 416-946-3223 416-978-3912 Fax deana.midmer@utoronto.ca http://dfcm19.med.utoronto.ca/research/alpha/default.htm Bibliography Reference: Midmer D, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Reid AJ, Stewart DE. (2005). A Reference Guide for Providers: The ALPHA Form-Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment Form. 3rd Edition. Toronto: University of Toronto, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Family & Community Medicine. CONTENTS THE ALPHA FORMS Purpose . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 THE REFERENCE GUIDE FOR PROVIDERS Using the Guide . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 RISK FACTORS 1. Family Factors Social Support . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Recent Stressful Life Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Couple’s Relationship . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Socioeconomic Status . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 24 26 28 2. Maternal Factors Late Onset Prenatal Care . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Prenatal Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Feelings About Pregnancy After 20 Weeks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Relationship With Parents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Self-Esteem Issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Emotional/Psychiatric History. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Depression in This Pregnancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 3. Substance Abuse Smoking During Pregnancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 48 Alcohol Use in Pregnancy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 50 4. Family Violence Childhood Experience of Family Violence . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Current or Past Woman Abuse . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Previous Child Abuse by Woman or Partner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Child Discipline. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54 56 58 60 RESOURCES . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62 ALPHA GROUP MEMBERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 63 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 64 5 THE ALPHA FORMS Overview National guidelines in Canada and the U.S. have stressed the importance of assessing the psychosocial health of the pregnant woman as a part of comprehensive obstetrical care. The ALPHA (Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment) Forms were developed as tools to facilitate the collection of psychosocial data during pregnancy in a structured, logical, and time-efficient manner. The ALPHA Form is available in a providercompleted or self-report version. Purpose of the ALPHA Forms The forms contain questions that focus on antenatal factors that have been found to be associated with poor or adverse postpartum outcomes. These outcomes include: child abuse (CA); woman abuse (WA), or intimate partner violence; postpartum depression (PD); and couple dysfunction (CD). Development Process An interdisciplinary group of obstetrical care providers1 began to meet in 1989 to explore the area of psychosocial assessment in pregnancy. We first surveyed family physicians to determine their current antenatal assessment strategy, the importance they ascribed to the adverse outcomes during the postpartum period, and their views on using a specially designed assessment tool to help them interview around these issues. Results indicated that they assessed sporadically, attributed high importance to adverse postpartum outcomes, and displayed a keen interest in using a comprehensive tool.2 Subsequently, we conducted a comprehensive and critical literature review to identify the antenatal 6 THE ALPHA FORMS factors associated with the adverse postpartum outcomes,3 which could be included in an assessment tool. Development of the Forms The initial version of the ALPHA Form was developed as a providercompleted tool. We tested the form in focus groups of providers from different disciplines (medicine, midwifery, and nursing) and used their feedback to modify the form further.4 We also developed the Provider’s Guide and a training video.5 We received feedback from pregnant women and nurses in our pilot study, that a self-report version would be helpful for those women without fluency in English. Some physicians also indicated a need for a self-report in order to minimize assessment time. Consequently we developed a self-report version of the form and tested it against the provider version on P.E.I.6 This study indicated that both versions of the form performed well, with equal utility, yield and provider and consumer satisfaction. A randomized controlled trial was conducted in Ontario with family physicians, obstetricians and midwives. The intervention group used the provider version of the ALPHA form while the control group provided usual care to pregnant women. Results indicated that ALPHA group providers were more likely than control providers to identify psychosocial concerns (odds ratio [OR] 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1-3.0; p=0.02) and to rate the level of concern as “high” (OR 4.8, 95% CI1.1-20.2; p=0.03). ALPHA group providers were also more likely to detect concerns related to family violence (OR 4.8, 95% CI 1.9-12.3; p=0.001). Using the ALPHA form helped health care providers detect more psychosocial risk factors for poor postpartum outcomes, especially those related to family violence. 7 THE ALPHA FORMS It is a useful prenatal tool, identifying women who would benefit from additional support and interventions.7 Concurrent with the ALPHA development process, the Ontario Medical Association (OMA) was revamping the Ontario Antenatal Record (OAR). The ALPHA group presented to the OMA committee on the OAR, and discussed the need for psychosocial assessment as part of the OAR. Changes to the OAR were made and the most recent iteration has several check-off boxes for psychosocial issues, with headings that reflect the headings on the provider ALPHA Form. Using the ALPHA Form facilitates the completion of this section on the OAR and provides the practitioner with a rich history of the woman’s life situation. [A full history of the ALPHA development process has been reported elsewhere.8] The Different ALPHA Versions On both ALPHA versions, the antenatal factors have been grouped intuitively by topic into four categories for ease of questioning during a clinical encounter, with suggested questions: Family Factors, Maternal Factors, Substance Use and Family Violence. Provider-completed ALPHA The provider-completed ALPHA Form has 35 questions relating to 15 antenatal factors. The questions are only suggestions, and providers are encouraged to modify the questions to suit the pregnant women in their practice and their practice style. On the provider version the adverse outcomes are abbreviated after each antenatal factor. Bold italics indicate a good association; regular print indicates a fair association. There is a 8 THE ALPHA FORMS column with check off boxes to indicate the concern over any antenatal factor. Space on the right of the form is available for notes. There is a list of resources at the end of the form to facilitate follow-up planning. Self-Report ALPHA The self-report has been expanded to 43 questions that have been formatted either with a ranking scale from 1-5 or with a yes/no response with room for comments. The associations with the adverse postpartum outcomes are not included on the form itself. The associations are printed on the provider recap or summary sheet that can be used with the selfreport version. The summary form also has a list of resources similar to the provider version. Both versions are included at the end of the chapter. They are also available at http://dfcm19.med.utoronto.ca/research/alpha 9 USING THE GUIDE 1. Interviewing Process The provider version can be completed in one session of about 20 minutes or over several prenatal visits. The woman should be advised in advance that her next appointment would be longer because of the assessment process. Providers can bill for counseling/psychotherapy when appropriate. The self-report version can be given to the woman to complete at the end of a visit or when she is waiting before a visit. It is not advisable for the woman to take the form home or to complete it if she is waiting with her partner. Some of the questions are very confidential in nature or relate to sensitive couple issues. It is recommended that either version of the form be completed after 20 weeks gestation. It is helpful to normalize the interview process by indicating that current practice is to ask all pregnant women about the psychosocial issues in their lives. Feedback from women in the pilot study and the study on P.E.I. revealed that the women enjoyed the interview process and found that it enhanced the provider’s understanding of their life situation. 2. Problem Identification The forms serve as means to identify antenatal factors associated with adverse postpartum outcomes. Early problem identification can lead to greater understanding and tailoring of care. Providers can collaborate with pregnant women around decision-making and the identification of the best intervention strategies. 10 USING THE GUIDE 3. Grouping of Factors The antenatal factors have been intuitively grouped into categories. These are: Family Factors, Maternal Factors, Substance Abuse, and Family Violence. The factors are arranged in order from less-to-more sensitive areas of inquiry. This layout facilitates the provider’s development of an interviewing rhythm with the pregnant woman. 4. Issues of Confidentiality Information elicited may be very confidential in nature. Except in the case of child abuse, which must be reported to children’s protective services, careful consideration and permission-seeking should occur before information is shared with others. It would be appropriate to share information with the other members of the health care team, including the family physician, obstetrician, midwife, pediatrician, community health nurse and perinatal nursing staff. 5. Causality is NOT Implied The antenatal factors are only associated with problematic postpartum outcomes. If an antenatal factor is identified, the woman will not necessarily experience an adverse outcome. Identifying the factor in the pregnancy allows the provider to engage in watchful-waiting to see if a postpartum problem begins to develop. 11 USING THE GUIDE 6. Identification of Resources It is incumbent on providers to identify resources that are appropriate and available. Smaller communities may not have extensive resources, or may have resources with long waiting lists or some distance away, making it difficult or impossible for some women to attend. 7. Cultural Competence Each culture has a rich social fabric. In some cultures, disclosure of psychosocial issues is rare and discouraged, and the use of outside resources is frowned upon. In other communities, elders are often arbiters and mediators. If an antenatal factor is disclosed, it would be appropriate to ask the woman, “In your culture, how is this issue managed/handled?” “Who would you tell about this problem?” 8. Interpreters Care must be taken when using interpreters. Because of the personal nature of the questions, it is advisable to use trained women interpreters. However, in some instances, because of the close inter-connectivity of some cultural groups, a woman may be reluctant to disclose sensitive issues to an interpreter she may meet in social situations. Using an interpreter who speaks the woman’s language but does not share her culture may be most appropriate. If interpreters are not available, it is wise to use non-family members and avoid using the woman’s spouse or children. Before beginning the ALPHA assessment, it is appropriate if the interpreter introduces herself, 12 USING THE GUIDE normalizes her presence at the interview, and assures the woman that the discussion will be kept private and confidential, in all areas, except in the area of child abuse. 9. Design of Guide The guide was developed for use as a quick reference tool. For this reason, many of the sections outlining suggestions for interventions are repeated in entirety, i.e., information on woman abuse. This repetition is not to be construed as an over-emphasis on any one psychosocial issue. 1 ALPHA Group: Family Physicians: Anne Biringer, June Carroll, Richard Glazier, Anthony Reid, Lynn Wilson; Psychiatrist, Donna Stewart; Anthropologist, Beverly Chalmers; Midwives, Maryn Tate, Freda Seddon; Nurse Educator/Researcher, Deana Midmer 2 Carroll JC, Reid A, Biringer A, Wilson L, Midmer D. Psychosocial Risk Factors During Pregnancy: What do Family Physicians ask about? Canadian Family Physician, 1994; 40:1280-1290. 3 Wilson L, Reid A, Midmer D, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Stewart DE. Antenatal psychosocial risk factors associated with adverse postpartum family outcomes. CMAJ, 1996; 15:785-791. 4 Reid A, Biringer A, Carroll JC, Midmer D, Wilson L, Chalmers B, Stewart DE. Using the ALPHA Form in practice to assess antenatal psychosocial health. CMAJ, 1998; 159(6): 677-684. 5 Assessing Psychosocial Health in Pregnancy: Using The ALPHA Form, 2003. Executive Producer. The Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto. 6 Midmer D, Bryanton J, Brown R. Assessing Antenatal Psychosocial Health Using Two Versions of the ALPHA Form. Canadian Family Physician: 2004;50:80-87. 7 Carroll JC, Reid AJ, Biringer A, Midmer D, Wilson L, Permaul JA, Pugh P, Chalmers B, Seddon F, Stewart DE. Effectiveness of the Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) form in detecting psychosocial concerns: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ 2005;173(3):253-9. 8 Midmer D, Carroll JC, Bryanton J, Stewart DE. From research to application: The development of an antenatal psychosocial health assessment tool. CJPH 2002; 93(4):291-6. 13 Please visit website for letter size forms at http://dfcm19.med.utoronto.ca/research/alpha Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment (ALPHA) Addressograph Antenatal psychosocial problems may be associated with unfavorable postpartum outcomes. The questions on this form are suggested ways of inquiring about psychosocial health. Issues of high concern to the woman, her family or the caregiver usually indicate a need for additional supports or services. When some concerns are identified, follow-up and/or referral should be considered. Additional information can be obtained from the ALPHA Guide. *Please consider the sensitivity of this information before sharing it with other caregivers. ANTENATAL FACTORS CONCERN FAMILY FACTORS Social support (CA, WA, PD) How does your partner/family feel about your pregnancy? Who will be helping you when you go home with your baby? £ Low £ Some £ High Recent stressful life events (CA, WA, PD, PI) What life changes have you experienced this year? What changes are you planning during this pregnancy? £ Low £ Some £ High Couple’s relationship (CD, PD, WA, CA) How would you describe your relationship with your partner? What do you think your relationship will be like after the birth? £ Low £ Some £ High MATERNAL FACTORS Prenatal care (late onset) (WA) First prenatal visit in third trimester? (check records) £ Low £ Some £ High Prenatal education (refusal or quit) (CA) What are your plans for prenatal classes? £ Low £ Some £ High Feelings toward pregnancy after 20 weeks (CA, WA) How did you feel when you just found out you were pregnant? How do you feel about it now? £ Low £ Some £ High Relationship with parents in childhood (CA) How did you get along with your parents? Did you feel loved by your parents? £ Low £ Some £ High Self-esteem (CA, WA) What concerns do you have about becoming/being a mother? £ Low £ Some £ High History of psychiatric/emotional problems (CA, WA, PD) Have you ever had emotional problems? Have you ever seen a psychiatrist or therapist? £ Low £ Some £ High Depression in this pregnancy (PD) How has your mood been during this pregnancy? £ Low £ Some £ High ASSOCIATED POSTPARTUM OUTCOMES The antenatal factors in the left column have been shown to be associated with the postpartum outcomes listed below. Bold, Italics indicates good evidence of association. Regular text indicates fair evidence of association. CA – Child Abuse CD – Couple Dysfunction PI – Physical Illness PD – Postpartum Depression WA – Woman Abuse COMMENTS/PLAN ANTENATAL FACTORS CONCERN COMMENTS/PLAN SUBSTANCE USE Alcohol/drug abuse (WA, CA) (1drink=11/2 oz liquor, 12 oz beer, 5 oz wine) How many drinks of alcohol do you have per week? Are there times when you drink more than that? Do you or your partner use recreational drugs? Do you or your partner have a problem with alcohol or drugs? Consider CAGE (Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye opener) £ Low £ Some £ High FAMILY VIOLENCE Woman or partner experienced or witnessed abuse (physical, emotional, sexual) (CA, WA) What was your parents’ relationship like? Did your father ever scare or hurt your mother? Did your parents ever scare or hurt you? Were you ever sexually abused as a child? £ Low £ Some £ High Current or past woman abuse (WA, CA, PD) How do you and your partner solve arguments? Do you ever feel frightened by what your partner says or does? Have you ever been hit/pushed/slapped by a partner? Has your partner ever humiliated you or psychologically abused you in other ways? Have you ever been forced to have sex against your will? £ Low £ Some £ High Previous child abuse by woman or partner (CA) Do you/your partner have children not living with you? If so, why? Have you ever had involvement with a child protection agency (i.e. Children’s Aid Society)? £ Low £ Some £ High Child discipline (CA) How were you disciplined as a child? How do you think you will discipline your child? How do you deal with your kids at home when they misbehave? £ Low £ Some £ High FOLLOW UP PLAN q Supportive counselling by provider q Additional prenatal appointments q Additional postpartum appointments q Additional well baby visits q Public Health referral q Prenatal education services q Nutritionist q Community resources / mothers’ group q Homecare q Parenting classes / parents’ support group q Addiction treatment programs q Smoking cessation resources q Social Worker q Psychologist / Psychiatrist q Psychotherapist / marital / family therapist q Assaulted women’s helpline / shelter / counseling COMMENTS: Date Completed Signature © ALPHA Group, April, 2005; Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto http://dfcm19.med.utoronto.ca/research/alpha q Legal advice q Children’s Aid Society q Other: q Other: q Other: q Other: THE ALPHA SELF-REPORT QUESTIONNAIRE FOR WOMEN Name Date Months Pregnant Having a baby usually means changes in your family life. You may wish to discuss some of these topics with your healthcare provider. She/he may help you with these changes. Please answer the questions the best way you can. Your answers are confidential and will be kept private. Please answer the questions by circling a number on the scale, writing an answer in the space, or marking “yes” or “no”. If some of the questions do not apply to you, please circle N/A (not applicable). YOUR FAMILY LIFE Please answer the following questions about your family life. Family Factors 1. About this pregnancy, my partner feels very happy 1 2. About this pregnancy, my family feels very happy 1 3. I feel supported in this pregnancy very much 1 4. My partner will be involved with the baby a great deal 1 5. When I am home with the baby I will have help from (state relationship) Comments: 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 5 5 5 5 very unhappy very unhappy not at all not at all Recent Life Stresses (moving, job change or loss, family illness or death, money troubles, and so on) 6. Over the past year, my life has been very relaxed 1 2 3 4 5 very stressful 7. I am making life changes during this pregnancy q No q Yes If yes, describe Comments: Relationship With Partner (if this applies) 8. My relationship with my partner is usually 9. After the baby, I expect my partner and I will get along Comments: YOUR OWN LIFE very happy very well 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 very unhappy not at all Please answer the following questions about your own life and feelings. 10. In this pregnancy, I first came for care when I was (indicate number) child. 11. I am planning to take prenatal classes Comments: months pregnant. This is my q Yes q No 1st 2nd 3rd Reasons, if no, Feelings About Being Pregnant 12. My feelings about this pregnancy at first 13. My feelings about this pregnancy now Comments: very happy very happy 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 very unhappy very unhappy Relationship With Parents 14. When I was a child, I got along with my parent(s) 15. As a young child I felt loved by my mother 16. As a young child I felt loved by my father Comments: very much very much very much 1 1 1 2 2 2 3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5 not at all not at all not at all Feelings About Becoming/Being a Mother 17. I have concerns about becoming/being a mother Comments: none at all 1 2 3 4 5 very many q No q Yes q No q Yes happy/up 1 2 3 4 5 sad/down Emotional Health 18. I have had some emotional problems 19. I have seen a psychiatrist/therapist 20. In this pregnancy, my mood has been usually Comments: N/A N/A CONCERNS IN YOUR LIFE Please answer the following questions about stress in your life. Alcohol and Drug Use During Pregnancy 21. Each week I drink drinks. (1 drink = 1 1/2 oz liquor, 12 oz beer, 5 oz wine) 22. There are times when I drink more during the week q No q Yes If yes, describe 23. Sometimes I’ve felt: A need to cut-down my drinking q No q Yes Annoyed by people criticizing my drinking q No q Yes Guilty about my drinking q No q Yes A need for a drink first thing in the morning q No q Yes 24. I use recreational drugs, e.g., marihuana 25. I have some drug problems 26. My partner uses recreational drugs, e.g., marihuana 27. My partner has some drug problems never 1 2 3 4 q No q Yes If yes, describe never 1 2 3 4 q No q Yes If yes, describe 5 very often 5 very often Comments: Parent’s Relationship (when you were a young child) 28. My parents usually got along very well 1 29. My father sometimes scared or hurt my mother never 1 30. My parents sometimes scared or hurt me never 1 31. As a child I was sexually abused q No q Yes 2 2 2 3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5 not at all very often very often N/A N/A N/A 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 a lot of tension great difficulty N/A N/A 2 2 3 3 4 4 5 5 very often very often N/A 2 3 4 5 very often N/A Comments: Relationship With Partner (if this applies) 32. My relationship with my partner usually has no tension 1 33. We work out arguments with no difficulty 1 34. I’ve sometimes felt scared by what my partner says or does never 1 35. I’ve been hit/pushed/slapped by a partner never 1 36. I’ve sometimes been put down or humiliated by my partner never 1 37. I’ve been forced to have sex against my will q No q Yes Comments: Raising Children 38. I have children not living with me q No q Yes 39. My partner has children not living with him q No q Yes 40. As a child, I was involved with Children’s Protective Services (Children’s Aid) 41. Children in my care have been involved with Children’s Protective Services q No q Yes q No q Yes Comments: 42. As a child, I was harshly disciplined by parents/family 43. I think spanking is necessary never never 1 1 2 2 3 3 4 4 Comments: 44. Overall, how concerned are you about your emotional and family life? not at all concerned 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 extremely concerned 45. What issues in your life are most concerning to you? 46. What help, if any, would you like? © ALPHA Group, April, 2005; Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto http://dfcm19.med.utoronto.ca/research/alpha 5 5 very often very often THE ALPHA SELF-REPORT QUESTIONNAIRE FOR WOMEN Addressograph Antenatal Psychosocial Health Assessment Provider Summary Antenatal psychosocial problems may be associated with unfavorable postpartum outcomes. Once the woman has completed the selfreport ALPHA, this form can be used to note her responses. Issues of high concern to the woman, her family or the caregiver usually indicate a need for additional supports or services. When issues of some concern are identified, follow-up and/or referral should be considered. Additional information can be obtained from the ALPHA Guide. Please refer to the other side of this page for information on antenatal psychosocial factors that are associated with problematic postpartum outcomes. Please consider the sensitivity of this information before sharing it with other caregivers. For specific information on how to deal with psychosocial issues refer to the Reference Guide for Providers or go to http://dfcm19.med.utoronto.ca/research/alpha FOLLOW UP PLAN q Supportive counselling by provider q Additional prenatal appointments q Additional postpartum appointments q Additional well baby visits q Public Health referral q Prenatal education services q Nutritionist q Community resources / mothers’ group q Homecare q Parenting classes / parents’ support group q Addiction treatment programs q Smoking cessation resources q Social Worker q Psychologist / Psychiatrist q Psychotherapist / marital / family therapist q Assaulted women’s helpline / shelter / counseling DATE (YY/MM/DD) SUMMARY/REFERRAL Date (YY/MM/DD) Signature q Legal advice q Children’s Aid Society q Other: q Other: q Other: q Other: FOLLOW-UP PROVIDER GUIDE FOR THE ALPHA SELF-REPORT QUESTIONNAIRE FOR WOMEN Problems in questions below have been shown to be associated with problematic postpartum outcomes. CA CD Child Abuse Couple Dysfunction PI PD Physical Illness Postpartum Depression WA Woman Abuse If a woman’s responses on the Self-Report ALPHA indicate psychosocial concerns, the following postpartum associations may apply. Bold italics indicates good association, regular type indicates fair association with adverse postpartum outcomes. FAMILY FACTORS 1. About this pregnancy, my partner feels 2. About this pregnancy, my family feels 3. I feel supported in this pregnancy 4. My partner will be involved with the baby 5. When I am home with the baby I will have help from 6. Over the past year, my life has been 7. I am making life changes during this pregnancy 8. My relationship with my partner is usually 9. After the baby, my partner and I will get along Lack of social support Lack of social support Lack of social support Lack of social support Lack of social support Recent stressful life events Recent stressful life events Couple dysfunction Couple dysfunction C A, C A, C A, CD, C A, C A, C A, CD, CD, WA, PD WA, PD WA, PD PD, WA, CA WA, PD WA, PD, PI WA, PD, PI PD, WA, CA PD, WA, CA Late onset prenatal care Refusal to attend/quitting Unwanted pregnancy after 20 weeks Unwanted pregnancy after 20 weeks Poor relationship with parents Poor relationship with parents Poor relationship with parents Low self-esteem Emotional/psychiatric history Emotional/psychiatric history Depression: prenatal & postpartum WA CA C A, C A, CA CA CA C A, C A, C A, PD Problematic substance use Problematic substance use Problematic substance use Problematic substance use Problematic substance use Problematic substance use Problematic substance use WA, WA, WA, WA, WA, WA, WA, Experience/witness abuse Experience/witness abuse Experience/witness abuse Experience/witness abuse Past/current intimate partner violence Past/current intimate partner violence Past/current intimate partner violence Past/current intimate partner violence Past/current intimate partner violence Past/current intimate partner violence Previous child abuse Previous child abuse Previous child abuse Previous child abuse Use of harsh discipline Use of harsh discipline C A, WA C A, WA C A, WA C A, WA WA, CA, PD WA, CA, PD WA, CA, PD WA, CA, PD WA, CA, PD WA, CA, PD CA CA CA CA CA CA MATERNAL FACTORS 10. I came for prenatal care when I was in 11. I am planning to take prenatal classes 12. My feelings about the pregnancy at first 13. My feelings about the pregnancy now 14. When I was a child, I got along with my parent(s) 15. As a child, I felt loved by my mother 16. As a child, I felt loved by my father 17. I have concerns about becoming/being a mother 18. I have had some emotional problems 19. I have seen a therapist/psychiatrist 20. In this pregnancy, my mood has been usually WA WA WA WA, PD WA, PD SUBSTANCE ABUSE 21. Each week I drink 22. There are times when I drink more during the week 23. Sometimes I’ve felt (CAGE questions) 24. I use recreational drugs 25. I have some drug problems 26. My partner uses recreational drugs 27. My partner has some drug problems CA CA CA CA CA CA CA FAMILY VIOLENCE 28. My parents usually got along 29. My father sometimes scared or hurt my mother 30. My parent(s) sometimes scared or hurt me 31. As a child I was sexually abused 32. My relationship with my partner usually has 33. We work out arguments with 34. I’ve felt scared by what my partner says or does 35. I’ve been hit/pushed/slapped by a partner 36. I’ve been put down or humiliated by my partner 37. I have been forced to have sex against my will 38. I have children not living with me 39. My partner has children not living with him 40. As a child I was involved with CAS 41. Children in my care have been involved with CAS 42. As a child I was harshly disciplined 43. I think spanking is necessary NOTE: Although low SES/financial concerns were not found to be associated with the poor postpartum outcomes, they were associated with Low Birth Weight. © ALPHA Group, April, 2005; Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto http://dfcm19.med.utoronto.ca/research/alpha FAMILY FACTORS Social Support Recent Stressful Life Events Couple’s Relationship Socioeconomic Status Family Factors SOCIAL SUPPORT Definition of Social Support FAST FACTS In its broadest sense, while Lack of social support has shown being modified and reshaped Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) ˆ woman abuse (WA) by culture, ethnicity, and family of origin, social support reflects an individual’s sense of belonging and safety with respect to a caring partner, Fair evidence of association with ˆ postpartum depression (PD) family or community. Some individuals have large support networks, and others have fewer people upon which to call for support. People get support in myriad ways, from interactions with family and friends to chat rooms on the internet. Lack of Social Support Insufficient social support during pregnancy is characterized by isolation; a lack of help when dealing with daily tasks, stressful events, or crises; and a lack of social, instrumental, and/or emotional support from a spouse, close friend or family member. The lack of support can range from severe-to-mild and is best articulated by the woman. Sometimes a scaling question is effective: On a scale of 1-to-10, with 1 being “very little” and 10 being “a lot”, how much support would you say you have in your life? Social Support and Culture Women who have recently relocated or immigrated to a new community may experience a lack of social support. This is particularly true for refugee women, who may experience a severe lack of support. The separation from 22 Family Factors SOCIAL SUPPORT their country of origin or from their cultural community may deeply compound feelings of isolation. A lack of literacy in English or French may further increase their sense of disconnection. How to Ask • How do your partner and/or family feel about your pregnancy? • What support do you get from your family, friends, and partner? • Who will be helping you when you go home with the baby? • What family and/or friends do you have in town? • Who do you turn to when you have a problem or when you’ve had a bad day? For immigrant and refugee women: If you were still in your country, what support would you get? How can you get support here in Canada? What to Do Options to consider if you determine that the woman is lacking social support: • Help her to understand the importance of and need for support after the baby is born. • Ask the woman to identify how she might increase the support in her life. • Consider additional visits during the pregnancy and postpartum periods. • Consider meeting with her partner and/or family. • Provide information about community groups for new mothers; encourage her joining. • Identify local resources that will provide culturally appropriate support. • Consider a referral to social work, PHN, or to homecare for postpartum support and follow-up. 23 Family Factors RECENT STRESSFUL LIFE EVENTS Definition of Stressful Events FAST FACTS Stressful events are those Stress and serious life problems have shown life experiences that require some degree of adaptation, with a resultant depletion of emotional reserves. Stressful events may be negative, e.g., financial problems, job loss, illness/death of a loved one, legal problems, and/or Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) ˆ woman abuse (WA) ˆ postpartum depression (PD) Fair evidence of association with ˆ physical illness (PI) household or work moves. Joyful events, such as marriages in the family or promotions and/or other opportunities at work, can also be stressful and require adaptation by the young family. Responses to Stress If over-stressed, individuals may resort to the stress-reduction behaviours modeled in their family-of-origin. These may include social withdrawal, abuse of alcohol or other substances, somatization, and/or inappropriate or violent venting of anger and frustration. These negative stress management strategies were often role-modeled by a parent, and the movement into parenting roles may evoke these problematic behaviours in the new parents. 24 Family Factors RECENT STRESSFUL LIFE EVENTS How to Ask • What major negative life changes have you experienced this year? For example, job loss, financial problems, illness/death of a loved one? • Have you had other stresses that are happy yet demanding of your energy? • Are you planning other changes during this pregnancy? • How do you usually cope with stress in your life? How does your partner cope? • How did your parents cope with stress when you were a child at home? • Tell me about a time when you managed stress well. What to Do Options to consider if you determine that the woman and/or her partner have experienced recent stress: • If appropriate, encourage the woman to discuss life stresses with her partner. • Advise against taking on additional, elective changes, if possible. • Consider meeting with her partner and/or family. • Identify what positive stress reduction strategies have been effective in the past, e.g., discussions with others, exercise, yoga, deep breathing, visualization, and relaxation exercises. • Identify what stress reduction strategies are being used that may be potentially harmful, e.g., use of alcohol or other substances, withdrawal, eating disorders. • Inquire at each visit about progress in this area and encourage small changes. • Provide information about community resources to learn about stress reduction. • Identify local resources that will provide culturally appropriate support. • Consider referral to a social worker or relaxation therapist. • Schedule extra visits for postpartum and well-baby care. 25 Family Factors COUPLE’S RELATIONSHIP Postpartum Couple Relationship FAST FACTS The strongest predictor of a Antenatal couple dysfunction and rigid traditional roles have shown good postnatal relationship is the quality of the relationship in the antenatal period. How couples rate their relationship antenatally is strongly correlated with the way they rate their relationship in the first postnatal months. Another Good evidence of association with ˆ couple dysfunction (CD) ˆ postpartum depression (PD) Fair evidence of association with ˆ woman abuse (WA) ˆ child abuse (CA) predictor is the quality of the marriage in their family of origin. If their parents were happy, they are also more likely to experience good couple functioning. The Traditional Postpartum Relationship Most marriages or partnerships become more traditional in the postpartum period by virtue of the woman’s increased emotional and financial dependence on her partner. Because of this shift in the spousal structure, women who hold less traditional role expectations may experience more marital dissatisfaction in the postpartum period, especially if there is rigid sex-role stereotyping of household tasks. 26 Family Factors COUPLE’S RELATIONSHIP How to Ask • How will your partner be involved in looking after the baby? • How do you share tasks at home? How do you feel about this? • Has your relationship changed since pregnancy? What will it be like after the baby? • Do you have any concerns about your relationship with your partner? • Are you traditional by nature? Is your partner? • In your culture, what usually happens in a couple relationship once the baby is born? What to Do Options to consider if you determine the woman is experiencing couple relationship difficulties: • Discuss the woman’s feelings about the relationship. What changes does she want? • Rule out woman abuse as an issue if there is any couple dysfunction. • Elicit what is a culturally appropriate intervention for the woman and her partner. • Encourage the couple to problem solve and seek solutions together. • Offer to see the couple together and provide office counseling, if appropriate. • Refer to a social worker, marital therapist, G.P. psychotherapist, or psychologist. 27 Family Factors SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS Low SES and Psychosocial Outcomes Low socioeconomic status (SES) by itself was not found to be an antenatal predictor for adverse postpartum family FAST FACTS Low socioeconomic status (SES) is not strongly associated with adverse birth outcomes or low birth weight (LBW) ˆ outcomes. However, adequate housing, appropriate nutrition, and enough money to survive Low SES may be a marker for other factors associated with LBW, such as smoking and povertyrelated low maternal weight are social determinants of health. The inability to meet basic survival needs and the experience of poverty may limit the capacity of individuals to feel safe and secure in their day-to-day lives. The constant and unrelenting stress and anxiety that can accompany jeopardized survival may be mitigating factors in the adverse postpartum outcomes of child abuse, woman abuse, couple dysfunction, and physical illness. How to Ask • Are you and/or your partner presently receiving pay for work? • What is your employment/occupational history? • How are you managing financially? • Do you have financial concerns/worries? • How do you think you will manage after the baby is born? 28 Family Factors SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS What to Do Options to consider if you determine the woman and family are financially stressed: • Ask the woman what financial strategies have worked in the past. • Determine how the financial stresses are impacting on the woman, e.g., poor nutrition. • Refer to a nutritionist, if appropriate. • Begin nutritional supplementation, if appropriate. • Identify community resources, including local food banks. • Identify problems the woman may have in relating to resources, e.g., language barrier. • Refer to a social worker, if appropriate. • Discuss different approaches to the problem, e.g., courses on budgeting, time management, money management, credit counseling. 29 MATERNAL FACTORS Late Onset Prenatal Care Prenatal Education (refusal or quit) Feelings About Pregnancy After 20 Weeks Relationship With Parents Self-Esteem Issues Emotional/Psychiatric History Depression in This Pregnancy Maternal Factors LATE ONSET PRENATAL CARE Seeking Prenatal Care FAST FACTS If a primiparous woman Late onset of prenatal care has shown does not start prenatal care Good evidence of association with ˆ woman abuse/intimate partner violence (WA) until the third trimester, this is a “red flag” for concern because of the association with intimate partner violence. It is important to inquire why there was a delay in seeking prenatal care. If a woman indicates that she has just moved into the area as the reason for seeking care late in pregnancy, it is wise to delve into this a little further. In some cases of intimate partner violence, constant location changes are part of the abuse pattern. It is also important to identify any cultural factors that impact on the woman’s decision to attend for care. In some instances, delayed care may be due to a denial of the pregnancy, mental illness or a scarcity of physicians. A woman may experience the following types of abuse: • emotional: being controlled by her partner; threatened with harm; denigrated, criticized and humiliated • physical: being hit, slapped, choked, pushed, burnt, whipped; objects thrown at her • sexual: sexual assault or rape; pressure to perform sexual acts unwillingly • financial: total financial dependence on partner; having to account for money spent • social: isolation in the community; denial of access to friends or family • spiritual: denied access to a church, temple or synagogue 32 Maternal Factors LATE ONSET PRENATAL CARE How to Ask • When did you first start prenatal care? • What is the reason you did not start prenatal care sooner? • In your culture, when do women usually seek care when pregnant? From whom? What to Do Options to consider if you determine/suspect the woman is being abused/assaulted: • Interview her alone; if necessary use an interpreter (non-family). • Explore the issue with care and sensitivity to cultural differences. • Reassure her about confidentiality and your concern for her health and welfare. • If IPV is disclosed, explain that it is not her fault and that no one has a right to hit another person. • Allow her to make decisions and take charge and control of her life. • Help her to explore her options: family, friends, hostel/shelter, and counseling. • Make her aware that violence can increase during pregnancy or after birth. • Determine whether the woman is safe in her home and help her develop a safety plan. • Indicate that you will support her whether she decides to stay with or leave her partner. • Make her aware of community resources: numbers of shelters, legal aid, support groups. • Make her aware that assault is a crime punishable by law, and keep detailed notes. • If danger is severe, request permission to consult with local police for advice. • Determine if other children in the family are at risk or are being abused. 33 Maternal Factors PRENATAL EDUCATION Attendance at Prenatal Classes If a primiparous woman refuses to attend prenatal classes or quits prenatal classes, this is associated FAST FACTS Refusal to attend or quitting prenatal classes has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) with an increased likelihood of child abuse. However, as with all maternal factors, it is important to look at the context of a woman’s life situation before drawing conclusions about her risk for postpartum difficulties. A woman may not attend classes because she and/or her partner do not speak the language in which they are given in her community. She may not choose to attend because she is single and classes are only offered to couples, because she is in a same-sex relationship and classes are heterosexual in orientation, because her partner refuses to attend, or because she can not afford the class fees. However, she may also not attend because she does not want the pregnancy. It is important to explore her reasons for non-attendance. This is particularly important if she comes from a demographic group where attending prenatal classes is a normal part of the pregnancy experience. If this is her second or other pregnancy, or if she is scheduled for an elective Caesarian, she may have no need of classes. How to Ask • Are you planning to take prenatal classes? If not, why not? • What were your reasons for quitting your prenatal classes? • In your culture, how do new mothers learn about giving birth? 34 Maternal Factors PRENATAL EDUCATION What to Do Options to consider if you determine the woman refuses or has quit prenatal classes: • Explore her feelings about the pregnancy and coming child. • Discuss any concerns she may have about the birth. • Determine whether the decision to not attend or quit classes is hers or her partner’s. • Offer alternative educational opportunities: readings, birth videos, private classes, and sessions with the office nurse. • Schedule extra well-baby visits and follow the family closely after birth. • Consider whether a visit by the PHN in the postpartum period is warranted. • Refer to a social worker, psychologist or counselor if appropriate. • If you have serious concerns, contact the CAS for general advice on how to intervene. • Consider whether this risk factor, in conjunction with other information about the family, indicates that CAS should be involved in the postpartum period. 35 Maternal Factors FEELINGS ABOUT PREGNANCY AFTER 20 WEEKS Feelings Towards Pregnancy Most women experience some ambivalence about being pregnant in the early weeks. It is helpful to discuss any ambivalence with the FAST FACTS Unwanted pregnancy after 20 weeks has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) ˆ woman abuse (WA) woman early in her pregnancy and offer her support. It is also important to determine a woman’s feelings later in the pregnancy, since an increased risk for child abuse is associated with an unwanted and unaccepted pregnancy after 20 weeks. This may also be an indication of distress in her relationship with her partner. Exploring the issue around intimate partner violence is also warranted. The woman may express unhappy feelings or demonstrate little interest in the pregnancy. In particular, it is important to determine a woman’s feelings about the pregnancy when she has initially decided to put the baby up for adoption and then changes her mind later in the pregnancy. How to Ask • How did you feel when you found out you were pregnant? How do you feel about it now? • How does your partner feel about the pregnancy? Your family? • In your culture, how do women describe their feelings about being pregnant? 36 Maternal Factors FEELINGS ABOUT PREGNANCY AFTER 20 WEEKS What to Do Options to consider if you determine the woman does not want or accept the pregnancy at 20 weeks: • Discuss the woman’s feelings further and help her explore her options. • Consider meeting with the woman and her partner together. • Schedule extra antenatal visits to provide a forum for discussion and/or counseling. • Refer to PHN or social worker, if appropriate. • Refer to a therapist, psychologist, or psychiatrist, if appropriate. • Schedule extra well-baby visits and monitor very closely. • Contact the CAS for general advice on how to intervene if rejection is severe and chronic. • Consider whether this risk factor, in conjunction with other information about the family, indicates that CAS or PHN should be involved in the postpartum period. Options to consider if you determine/suspect the woman is being abused/assaulted: • Interview her alone; if necessary use an interpreter (non-family). • Reassure her about confidentiality and explain that it is not her fault. • Help her to explore her options: family, friends, hostel/shelter, and counseling. • Determine whether the woman is safe in her home and help her develop a safety plan. • Indicate that you will support her whether she decides to stay with or leave her partner. • Make her aware of community resources: numbers of shelters, legal aid, support groups. • Make her aware that assault is a crime punishable by law, and keep detailed notes. • If danger is severe, suggest that she consult with local police for advice. 37 Maternal Factors RELATIONSHIP WITH PARENTS Quality of Relationship With Parents If a pregnant woman describes herself as having had a poor relationship with FAST FACTS A poor childhood relationship with parents has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) her parents when growing up, there is an association with child abuse in the future. For example, a woman may describe herself as having had conflict and a lack of closeness with her mother, or she may have had feelings that her parents were displeased with her as a child. She may also have felt unaccepted by her family of origin, or describe the parenting she received as cold and rejecting. However further exploration is necessary. Many women who were reared by cold or non-engaged parents make a conscious decision to mother in a different manner, with love and warmth. Also, if opportunities arise, it would also be important to pursue the following lines of questioning with the woman’s partner as well. How to Ask • As a child, did you feel loved by your parents? • How do you get along with your parents now? How did you get along as a child? • In what ways will you parent like your parents did? What would you do differently? • In your culture, what is the usual way of parenting? Of disciplining? Of showing affection? 38 Maternal Factors RELATIONSHIP WITH PARENTS What to Do Options to consider if you determine the woman had a poor childhood relationship with her parents: • Discuss how this may affect her mothering. • Ask the woman to identify how she can develop a strong bond with her infant. • Refer for infant-parent attachment therapy, if appropriate and/or available in your area. • Refer to mothering/parenting classes through prenatal education/community resources. • Refer to a new parent support group, if appropriate. • Monitor closely and schedule extra visits postpartum, if necessary. • Refer to PHN, social worker, psychologist or counselor, if appropriate. • Consider whether this risk factor, in conjunction with other information about the family, indicates that CAS should be involved in the postpartum period. 39 Maternal Factors SELF-ESTEEM ISSUES Definition of Self-Esteem FAST FACTS Self-esteem can be defined Low maternal self-esteem has shown as self-respect or having a Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) favorable opinion of oneself. A woman with healthy selfesteem would feel good about herself and see herself Fair evidence of association with ˆ woman abuse (WA) as generally successful in life. Many primiparous women have some anxiety around infant care, yet they also have secure and positive feelings about their mothering skills. Lack of Maternal Self-Esteem Women who view themselves as unsuccessful in life often regard themselves negatively and have insecure feelings about their future mothering skills. These feelings of insecurity may be related to how they viewed their mother’s feelings of competence and her ability as a parent. There is a good correlation between low maternal self-esteem and child abuse and a fair correlation with woman abuse. How to Ask • What concerns do you have about becoming/being a mother? • What sort of mother do you think you’ll be? • How do you picture yourself as a mother? • What was your mother like? 40 Maternal Factors SELF-ESTEEM ISSUES • In your culture, what are mothers expected to be like? • In your culture, how are mothers supposed to act or behave? What to Do Options to consider if you determine that the woman has poor self-esteem or negative expectations of mothering: • Discuss during visits and provide on-going support and follow-up. • Meet with woman and her partner, if appropriate. • Schedule extra well-baby visits and monitor closely postpartum. • Identify situations when the woman has had higher self-esteem and encourage her to seek out more of these situations. • Refer to prenatal education or community for mothering groups or new parent groups. • Refer to a social worker, psychologist or counselor, if appropriate. • Refer for infant-parent attachment therapy, if available in your area. 41 Maternal Factors EMOTIONAL/PSYCHIATRIC HISTORY Past History of Emotional or Psychiatric Problems During the course of prenatal care, it is important to determine whether the woman has experienced a psychiatric disorder in the past or present because of FAST FACTS A history of psychiatric or emotional problems has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) ˆ woman abuse (WA) Fair evidence of association with ˆ postpartum depression (PD) the strong association with postpartum mental illness, child abuse and woman abuse. Specifically, the conditions that have been found to be important include depression, anxiety, bipolar affective disorders, schizophrenia, chronic psychiatric problems, or a history of past or present psychiatric treatment. If a woman presents with an untreated major mental illness during pregnancy, immediate referral to a psychiatrist is essential. How to Ask • Have you ever had emotional problems? How serious were they? Were you taking any medication? • Have you ever seen, or are you seeing, a psychiatrist or therapist? • How would you describe your current emotional/mental health? • In your culture, what does a woman do if she has serious emotional/ psychiatric problems? 42 Maternal Factors EMOTIONAL/PSYCHIATRIC HISTORY What to Do Options to consider if you determine the woman has/had serious emotional or psychiatric problems: • Assess the woman’s current state of emotional/mental health. • Identify extra social support resources that might be available for the woman in the postpartum period. • Schedule extra antenatal visits for monitoring and follow-up. • Monitor carefully for postpartum depression disorders or flare-ups of other psychiatric disorders. • Refer to a PHN, social worker, a psychologist, or homecare, if appropriate. • Refer to a therapist for counseling, if the disorder is mild. • Refer to a psychiatrist for assessment and treatment if the disorder is moderate or severe. 43 Maternal Factors DEPRESSION IN THIS PREGNANCY Depression in Pregnancy In general, 10-15% of new mothers experience a postpartum depression and approximately the FAST FACTS A history of depression or anxiety in this pregnancy has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ postpartum depression (PD) same number experience depression during pregnancy. Numerous studies have shown that if a woman is clinically anxious or depressed during her pregnancy, she is at higher risk for a postpartum mood or anxiety disorder. Other factors that increase her risk of experiencing postpartum depression include previous depression, recent serious life stress, a lack of social support, couple relationship problems, a family history of depression, previous other emotional and/or psychiatric problems, a previous postpartum depression, and a difficult infant. A woman may develop a postpartum mood or anxiety disorder immediately after birth or at any time in the first postpartum year. How to Ask • How has your mood been during this pregnancy? • Have you felt low, very tense, or depressed at times during this pregnancy? If yes, for how long? • Were you anxious or depressed during or after previous pregnancies? • Did you take medication to manage a previous depression or anxiety? 44 Maternal Factors DEPRESSION IN THIS PREGNANCY What to Do Options to consider if you determine the woman is at risk for a postpartum mood or anxiety disorder: • Provide close follow-up before and after delivery. • Schedule a visit with the woman and her partner to discuss postpartum mood and anxiety disorders. • Schedule extra visits early after birth and monitor the woman’s mental health closely. • Identify extra social support resources that might be available for the woman postpartum. • Refer to community support and self-help groups. • Refer to a PHN, homecare, social worker, therapist, and/or psychiatrist, if appropriate. • Consider the use of antidepressants in pregnancy and during the postpartum period, if needed. 45 SUBSTANCE ABUSE Smoking During Pregnancy Alcohol Use in Pregnancy Substance Abuse SMOKING DURING PREGNANCY Smoking During Pregnancy Numerous studies have shown a strong correlation between smoking during pregnancy and low birth FAST FACTS Smoking during pregnancy has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ low birth weight (LBW) weight. It is important to determine whether the woman is a smoker, her degree of addiction to nicotine, and whether she is planning to quit. It is also important to determine if she is smoking substances other than tobacco, and whether her partner or other household members smoke. How to Ask • Do you currently smoke or are you an ex-smoker? • If you currently smoke, how many cigarettes do you smoke each day? • Would you like help in trying to quit smoking? Have you ever quit before? • Does your partner or someone else in the home smoke? • Do you smoke other substances besides tobacco? What to Do Options to consider if you determine that a woman or her partner smoke tobacco: • Identify why she is smoking: stress reduction, social habit, weight management, etc. • Identify previous quitting strategies the woman has employed. 48 Substance Abuse SMOKING DURING PREGNANCY • Discuss the problems and risks of smoking for the health of the fetus. • Discuss the impact of smoking and second hand smoke on the infant, especially with respect to SIDS. • Suggest she quit or cut down, and provide strategies for doing so. • Consider enlisting her partner’s and family’s support, if appropriate. • Encourage her partner to quit or cut down (if appropriate), or to smoke out of the home. • Refer her to a smoking cessation program, if desired. • Refer her to a program to help her quit using other substances. Resources Provincial Smoker’s Helplines: • BC 1-877-455-2233 • SK 1-877-513-5333 • PEI 1-888-8186300 • AB 1-866-332-2322 • NS 1-877-513-5333 • NFLD 1-800-363-5864 • NB 1-877-513-5333 • NNV 1-866-877-3845 • QC 1-888-853-6666 • YK • ON 1-877-513-5333 • NWT No line • MB 1-877-513-5333 1-800-661-0408 (x8393) www.pregnets.com www.addictionmedicine.ca 49 Substance Abuse ALCOHOL USE IN PREGNANCY Consequences of Alcohol or Substance Use in Pregnancy Abuse of alcohol or other substances by the woman or her partner is an important antenatal risk factor, both FAST FACTS The use of alcohol during pregnancy has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ woman abuse (WA) Fair evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) medically and psychosocially. Alcohol use in pregnancy may result in a Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (e.g., Fetal Alcohol Effects or Fetal Alcohol Syndrome). Associated psychosocial risk factors include child abuse and woman abuse. Heavy use of alcohol may be determined from self-report, a history of black-outs, need for an “eye-opener”, loss of control, dependency on alcohol, and hallucinations or delirium tremens in the abstinence phase. The use of illicit drugs can be determined by urine assay or self-report. Abuse of sedative, hypnotic or prescription narcotics can be associated with significant postpartum difficulties. How to Ask • How many standard drinks do you have per week? (1½ oz. liquor, 12 oz. beer, 5 oz. wine) • Are there times when you drink more? If yes, how much? • Do you use alcohol to help manage stress in your life? • Do you feel that you or your partner has a problem with alcohol or drugs? • Does your partner pressure you to use alcohol or other drugs? 50 Substance Abuse ALCOHOL USE IN PREGNANCY Cage Screen: C Have you felt you ought to cut down your drinking A Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? G Have you felt bad or guilty about your drinking? E Have you ever needed an eye-opener in the morning to get going? (2 or more positive answers of “sometimes” or “quite often” warrant in-depth assessment) What to Do Options to consider if you determine a woman or her partner abuse alcohol or other substances: • Identify “triggers” for alcohol and/or substance use. • Identify pros/cons of current alcohol or substance use. • Discuss times when the woman uses less alcohol and/or substances, and encourage her to employ these strategies more often. • Help woman develop an action plan for dealing with triggers. • Inform woman of the risks and problems for the health of the woman and fetus. • Assess woman’s willingness to cut down or stop. • Refer to a treatment program, if appropriate. • Offer to assess partner’s alcohol or drug use. Resource Specialized Programs www.addictionmedicine.ca Montreal : Herzl Family Practice Clinic, 514-340-8253 www.pregnancyaddiction.ca Toronto: Toronto Centre for Substance Use in Pregnancy, 416-530-6036 Vancouver: Sheway Maternity Clinic, 604-216-1699 51 FAMILY VIOLENCE Childhood Experience of Family Violence Current or Past Woman Abuse Previous Child Abuse by Woman or Partner Child Discipline Family Violence CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCE OF FAMILY VIOLENCE Experienced or Witnessed Violence If a pregnant woman or her partner either experienced violence or witnessed violence during childhood, they are at higher risk of violence in their own family. Violent childhood experiences FAST FACTS Experience/witness of abuse by woman/partner has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) Fair evidence of association with ˆ woman abuse (WA) can include physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse. There is a good correlation between the childhood experience or witnessing of abuse and child abuse, and a fair correlation with postpartum intimate partner violence. How to Ask • What was your parents’ relationship like? How did they get along? • Did you ever see your father (or your mother’s partner) scaring/hurting your mother? • Have you ever been hit or scared by (either of) your parents or other family caregivers? How often? • In your culture, what happens when there is violence in the family? 54 Family Violence CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCE OF FAMILY VIOLENCE What to Do Options to consider if you determine or suspect that child abuse may be a problem: • Discuss parenting problems in current situation. • Schedule extra well-baby visits to monitor closely and provide follow-up. • Refer to parenting classes and/or new parents support groups. • Refer to a social worker, PHN, psychologist or for counseling, if appropriate. • Refer to CAS, if appropriate. If you determine that woman abuse may be a problem: • Interview her alone; if necessary use an interpreter (non-family). • Explore the issue with care and sensitivity to cultural differences. • Reassure her about confidentiality and your concern for her health and welfare. • Explain that it is not her fault and that no one has a right to hit another person. • Allow her to make decisions and take charge and control of her life. • Help her to explore her options: family, friends, hostel/shelter, and counseling. • Make her aware that violence can increase during pregnancy. • Determine whether the woman is safe in her home and help her develop a safety plan. • Indicate that you will support her whether she decides to stay with or leave her partner. • Make her aware of community resources: numbers of shelters, legal aid, support groups. • Make her aware that assault is a crime punishable by law, and keep detailed notes. • If danger is severe, suggest she consult with local police for advice. • Determine if children in the family are at risk or are being abused. 55 Family Violence CURRENT OR PAST WOMAN ABUSE Woman Abuse FAST FACTS Woman abuse (intimate partner violence) and child abuse are under-reported by patients and under-diagnosed by health care providers. Studies have shown that pregnancy is a high-risk time for woman abuse. Current or past woman abuse, or intimate partner violence, has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ postpartum woman abuse (WA) Fair evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) ˆ postpartum depression (PD) If a pregnant woman has experienced or is currently experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) by her partner, she is at high risk of abuse during the rest of the pregnancy and during the postpartum period. There is also fair evidence that current or past IPV is associated with child abuse and postpartum depression. Woman abuse can be emotional, physical, sexual, financial, social and spiritual. How to Ask • How do you and your partner solve arguments? • Have you ever been hit/pushed/shoved by your partner? • Do you ever feel frightened by what your partner says or does? • Does your partner ever humiliate you or psychologically abuse you in other ways? • Have you ever been forced to have sex against your will? • In your culture, what does a woman do if she is experiencing intimate partner violence? 56 Family Violence CURRENT OR PAST WOMAN ABUSE What to Do Options to consider if you determine or suspect that the woman is being abused: • Interview her alone; if necessary use an interpreter (non-family). • Explore the issue with care and sensitivity to cultural differences. • Reassure her about confidentiality and your concern for her health and welfare. • Explain that it is not her fault and that no one has a right to be violent. • Allow her to make decisions and take charge and control of her life. • Determine whether the woman is safe in her home and help her develop a safety plan. • Indicate that you will support her whether she decides to stay with or leave her partner. • Make her aware of community resources: numbers of shelters, legal aid, support groups. • Make her aware that assault is a crime punishable by law, and keep detained notes. • If danger is severe, request permission to consult with local police for advice. If you have determined that child abuse may be a problem: • Discuss parenting problems in current situation. • Schedule extra well-baby visits to monitor closely and provide follow-up. • Refer to parenting classes and/or new parents support groups. • Refer to a social worker, PHN, psychologist, or psychiatrist, if appropriate. If a woman discloses IPV, consult with Child Protective Services if there are other children in the home, even if the woman says they are not being abused or do not witness the violence. 57 Family Violence PREVIOUS CHILD ABUSE BY WOMAN OR PARTNER Definition of Child Abuse FAST FACTS Child abuse, or child Previous child abuse by the woman or partner has shown endangerment, is the deliberate act of physically, sexually, or emotionally Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) assaulting and/or violating a child’s rights or person. If either the pregnant woman or her partner has ever been officially reported to have committed any form of child abuse or if a child of theirs has ever been placed in foster care, there is a significant risk of abuse to the child the woman is carrying. Notification of Children’s Aid Society All health care providers and adults connected with the child and family, e.g., teachers, are bound by law to notify the appropriate child protective services (CPS) in their area if they have suspicion that a child is being abused. Contacting CPS services should not be delegated. Health care professionals are considered to have a greater burden of expectation regarding assessing for abuse, and have greater liability if they do not report. If there is no child living in the home, but the provider is concerned about risk to the newborn, the women should be encouraged to contact her local CPS agency to request aftercare support. Women who contact the local CPS voluntarily feel more control and tend to view the agency as helpful rather than punitive. 58 Family Violence PREVIOUS CHILD ABUSE BY WOMAN OR PARTNER How to Ask For multiparous women or women whose partner’s have children: • Do you have any children who are not living with you? If so, why not? • Does your partner have children? Are they living with you? If no, where are they living? • Was CAS involved with your family when you were a child? If there are children in foster care: • Why aren’t they living with you? What to Do Options to consider if you determine that there has been previous child abuse: • Discuss parenting issues and/or problems in current situation. • Schedule extra well-baby visits to monitor closely and provide follow-up. • Refer to parenting classes and/or new parents support groups. • Refer to a social worker, PHN, psychologist or counselor, if appropriate. • Suggest the woman contact the child protection services agency herself in order to elicit help. • Contacts CAS if concerns or suspicions exist and speak to a worker to determine status of case, i.e., whether it is open. 59 Family Violence CHILD DISCIPLINE Child Discipline FAST FACTS The use of corporal punishment, such as frequent and hard spanking, or the use of physical punishment of a baby prior to crawling; A history of harsh discipline has shown Good evidence of association with ˆ child abuse (CA) excessive cursing at a child; withholding food, shelter, and basic requirements for healthy living; as well as deliberate emotional rejection are examples of harsh discipline and may be considered child abuse. There are strong cultural components to child rearing and much behaviour observed at face value may be culturally appropriate to the family. Culture is not limited to ethnicity. Families have individual cultures, as do demographic groups, e.g., teens. It is important to ask parents not only about their parenting beliefs but also about the parenting beliefs of members of their extended families who may be involved in child rearing. How to Ask • How do you think you will discipline your child? How will your partner discipline? • If family members will be caring for the baby, how will they discipline? • How do you deal with your children at home when they misbehave? • How did your parents discipline you? Were you ever spanked? • In your culture, what is the usual way children are disciplined in the family? 60 Family Violence CHILD DISCIPLINE What to Do Options to consider if you determine the woman/partner may use harsh discipline: • Discuss with the woman, and her partner if appropriate. • Determine cultural influences, if any, on parenting practices. • Inform parents that you have a legal obligation to report suspicions of child neglect or abuse to the CAS. • Monitor closely during infancy and continue to follow up during childhood. • Refer parents to parenting classes and support groups. • Refer to a social worker, PHN, psychologist, or for counseling, if appropriate. • Consider whether this risk factor, in conjunction with other information about the family, indicates that CAS could be involved in the postpartum period. 61 RESOURCES Please use this sheet to write in the telephone numbers of resources available in your community. Contact/Telephone Contact/Telephone Addiction Treatment Programs Parents Support Group Assaulted Woman’s Helpline Prenatal Education Services Children’s Aid Society Psychotherapist Community Centre Psychiatrist Family Service Association Psychologist Homecare Public Health Nurse Infant-Parent Attachment Therapy Relaxation Therapy Course Kid’s Help Line Social Worker Legal Aid Smoking Cessation Courses Marital/Family Therapist Women’s Crisis Line Nutritionist Women’s Shelter Parenting Classes Woman’s Support Group Teaching Resources VIDEO: The ALPHA Form: Assessing Antenatal Psychosocial Health. A 20 minute interactive training video for providers. Available through the Department of Family and Community Medicine, 263 McCaul Street, 5th Floor, Toronto, M5T 1W7, ON, Canada. 416-946-3223, Fax. 416-978-3912 Attn. D. Job $29.00 plus tax and postage. Additional copies of the ALPHA Guide can be obtained from the Department of Family & Community Medicine, address above, for $15.00 plus tax and postage. Training workshops may also be arranged. Contact Dr. Deana Midmer for more information. deana.midmer@utoronto.ca 62 ALPHA GROUP MEMBERS Anne Biringer, MD, CCFP Associate Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto; Family Physician, Mount Sinai Hospital Family Medicine Centre June C. Carroll, MD, CCFP, FCFP Sydney G. Frankfort Chair in Family Medicine, Associate Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto; Family Physician, Ray D. Wolfe Department of Family Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto, Ontario Beverley Chalmers, PhD Adjunct Professor, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario Deana Midmer, BScN, EdD, FACCE Associate Professor & Research Scholar, Department of Family & Community Medicine, University of Toronto; Co-ordinator, Prenatal & Family Life Education, Mount Sinai Hospital Anthony J. Reid, MD, MSc, CCFP Associate Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto; Family Physician, Orillia, Ontario Donna E. Stewart, MD, FRCP(C) Professor of Psychiatry, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Family & Community Medicine; Lillian Love Chair Women’s Health, The University Health Network, University of Toronto Lynn Wilson, MD, CCFP Associate Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto; Family Physician-in-Chief, St. Joseph’s Health Centre 63 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The ALPHA Group wishes to acknowledge the contributions of the Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, for administrative support during the development of the project. Printing of this guide was generously supported by the Lawson Foundation. 64