Bad Portraits Guide

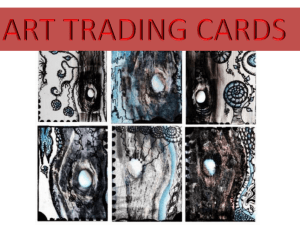

advertisement

Curated by Xanthe Isbister, Esplanade Arts and Heritage Centre Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program The Esplanade Arts and Heritage Centre is where the stories of our great collective culture are told in music and dance, painting and sculpture, plays and concerts, exhibitions and installations, artifacts and objets d’art, education programs and private events. Featuring a 700-seat main stage balcony theatre which boasts superior technology and striking design, the Esplanade is where Medicine Hat celebrates arts and heritage. A marvel of contemporary Canadian architecture on traditional Blackfoot territory just steps from the South Saskatchewan River, the Esplanade occupies an eminent position on downtown’s historic First Street Southeast. From its rooftop terrace, you can see Saamis, the dramatic shoreline escarpment which is the setting for the story of how Medicine Hat got its name. Inside, visitors discover the vibrant Esplanade Art Gallery, the prized Esplanade Museum, the Esplanade Studio Theatre across the lobby from the Esplanade Main Stage Theatre, the expansive Esplanade Archives and Reading Room, an art education space called the Discovery Centre, the catering-friendly Cutbanks Room, the McMan Bravo Coffee House and lots of volunteers and staff who are eager to guide you to the right place—and tell you their versions of our city’s namesake tale on the way. In the northeast corner of the Esplanade grounds stands the oldest remaining brick home in Alberta, the Ewart-Duggan House. With its gingerbread trim and quaint heritage gardens, it now serves as a charming venue for select cultural events and a home away from home for artists in residence. The Esplanade opened in celebration of Alberta’s centennial in 2005 and ever since, Medicine Hat has welcomed a steady procession of artists and audiences, storytellers and story-lovers from around the region and around the globe. The celebration continues today. The Alberta Foundation for the Arts (AFA) has supported a provincial travelling exhibition program since 1981. The mandate of the AFA’s Travelling Exhibition Program (TREX) is to provide all Albertans the opportunity to enjoy visual art exhibitions in their community. Three regional galleries and one arts organization coordinate the program for the AFA: Northwest Region: The Art Gallery of Grande Prairie, Grande Prairie Northeast and North Central Region: The Art Gallery of Alberta, Edmonton Southwest Region: The Alberta Society of Artists, Calgary Southeast Region: The Esplanade Arts and Heritage Centre, Medicine Hat Each year, more than 300,000 Albertans enjoy many exhibitions in communities ranging from High Level in the north to Milk River in the south and virtually everywhere in between. The Alberta Foundation for the Arts TREX Program also offers educational support material to help educators integrate the visual arts in the school curriculum. Exhibitions for the TREX program are curated from a variety of sources including private and public collections. A major part of the program consists of making the AFA’s extensive art collection available to Albertans. This growing collection is comprised of more than 8,000 artworks which showcase the talents of more than 2,000 artists. As the only provincial art collection in Alberta, it chronicles the development of the province’s vibrant visual arts community and serves as an important cultural legacy for all Albertans. Bad Portraits is an exhibition of twenty-four gouache and watercolour paintings that are rapidly rendered and highly engaging portraits of people who submitted pictures of themselves to Calgary artist Mandy Stobo. The paintings showcase Stobo’s quick and concentrated style. She starts with a swift line drawing in black gouache then loosely paints in the image. Her racy colours and speedy lines seem to capture candid moments and that most evasive human quality in the urban environment, unguarded expression. Yet for these apparently intimate creations, the artist depends on connections she makes online. She solicits models and subjects, engages in trade, promotes a range of art products and connects with a large audience at mandystobo.com and through Facebook, Google+ and Twitter. Bad Portraits emphasizes the duality of a wired world in which, as psychologist and author Sherry Turkle wrote in the New York Times in April, 2013, “texting, email and posting let us present the self we want to be… we can edit and… we can delete.” Stobo’s project resides in the same online world but its participants have no control over the outcome of the pieces since they volunteered to be subjects of art that is admittedly bad. “Bad” is not intended by Stobo to be interpreted literally. The adjective alters viewers’ expectations and relieves Stobo of any pressure to create conventional portraits. It also removes expectations from the minds of those who submit their pictures. Amanda (Mandy) Stobo insists on making play of art—celebrating the process and engaging people. She captures in her images the effervescent moments of comedy and tragedy that are at the heart of play and at the heart of life. Born in Calgary in 1983, Stobo has run a professional practice as a painter, illustrator and collaborator since 2003. Her travels and successes in places like Australia, Cambodia and Thailand and the British Columbia interior inluenced her tremendously by afirming the value of the wonderful spontaneity that inspires her technique and infuses her images. In 2006, she established a studio in her hometown and since then, has constructed an online presence which is as central to her practice as her physical presence on the urban art scene. Paintings from the Bad Portraits Project hang in private collections in nine countries and Stobo is launching the project in Toronto, New York and Los Angeles. Her works have been commissioned for the sets of ilms like Angel’s Crest, (2011,) and the award-winning Not Far from the Abattoir, (2011,) and for TV series like The Wire, (2002-2008.) She illustrated the children’s book, C is for Calgary, and her works of public art add lashes of colour and an element of playfulness to the streets of downtown Calgary. Stobo has collaborated with renowned contemporary visual artists like Annie Preece and with musical artists like Michael Bernard Fitzgerald, Library Voices and The Dudes on album cover designs and other music merchandise. And in the wake of the devastating looding in Calgary in June, 2013, her campaign to sell Bad Portraits T-shirts online raised more than $20,000 in donations for relief programs. A former student of the Alberta College of Art + Design, Stobo is constantly expanding the scope of her art and widening the circle of those she invites to play. She asks us to enjoy ourselves as we participate in her experiments with technique, her examination of the relationship between beauty and perception and our mutual search for expression and community. Opposite: Jeremy Fokkens, Mandy Stobo, 2013 The images in Bad Portraits deviate so wildly from the conventions of portraiture that they might even be considered, as the artist playfully suggests, bad examples of the art. “You send me your face,” she writes at badportraitproject.com. “And I make you bad.” While Mandy Stobo departs from the norm with her choice of media and madcap style, her method of selecting subjects is also new and curious. In 2011, she began painting her signature portraits of family, friends and celebrities caught with lively expressions or depicted with boldly exaggerated features. The subjects wear comic or tragic faces and appear to be arrested in conversation or mid-movement, characteristics which portrait artists usually take pains to avoid. And the paintings appear to have been quickly rendered as though the artist rushed to capture the personalities before they slipped back into their busy lives. Traditional portraiture, in comparison, requires models to sit still, sometimes for hours. Stobo got the idea for painting bad portraits while analyzing avatars and proile pictures on social media sites. She posted a request for personal pictures on her web site and chose subjects of varying ages and appearances for the Bad Portrait Project from the submissions she received. She made bad portraits of celebrities and tweeted the unsolicited images to their Twitter accounts. To her surprize, people like George Stroumboulopoulos, Conan O’Brien and Jimmy Fallon responded with praise and amazement. And publicity for her product. The Bad Portraits project shatters the expectations of those who participate as subjects. By submitting pictures, they virtually relinquish their rights to vanity along with any pretense of getting a “good” picture of themselves in the end. In an age when the ease, quality and creative potential of digital photography and photoediting seem to have given rise to the incessant posting of calculatedly lattering and expressionless proile pics online, Stobo is changing the way people present themselves to the world. She now receives orders for portraits almost daily and her web site gets as many as 87,000 hits a week. In a Calgary Journal interview in November, 2012, she said her work depends on linking up with people online. “I can’t imagine being an artist in a different time,” said Stobo. “It would be impossible to do what I do without social media.” Stobo launched Bad Portraits via social media in order to maximize the number of connections she could make and it serves her purposes well. It is both the vehicle for her open invitation and the conduit for a never-ending supply of diverse and willing subjects. Just as Stobo abandoned the traditional approach to conducting the business of art, the images in Bad Portraits reject standards of traditional portraiture in favour of candour, immediacy and untamed execution. They may be bad portraits but as their popularity attests, they are very good paintings of people. The twenty-four images in Mandy Stobo: Bad Portraits are from the collection of the artist. 1. SG, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 30 x 18 cm. 2. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 30 x 18 cm. 3. JT, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 30 x 18 cm. 4. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 5. GD, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 6. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 7. SM, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 8. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 9. JOSH BECK! 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 10. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 11. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 12. CS, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 13. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 14. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 15. BV, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 16. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 17. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 18. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 19. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 20. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 21. RR, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 22. Untitled, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 23. Alex Meenehan, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. 24. Jennifer Geisbrecht, 2012. Gouache, watercolour and ink on paper, 18 x 30 cm. The lesson plans for Mandy Stobo: Bad Portraits are designed to entice people to do as Stobo does and play with paint and portraiture. Each lesson is centred on producing a work of art and lists easy-tofollow instructions. Students at all levels will be amazed at how much they can learn by trying new ways to make art, exploring the challenging discussion questions and just enjoying the pictures in Bad Portraits. The student will: Sketch a self-portrait Be introduced to the concepts of representational and igurative art Apply fundamental principles of portraiture such as framing and proportion Explore methods of altering appearances Gain a new understanding of the paintings in Bad Portraits The amusing title of Mandy Stobo’s exhibition, Bad Portraits, implies there is such a thing as a good portrait. Drawing or painting a successful portrait of a person greatly depends on the artist’s understanding of the proportions of the human face. The word, “portrait,” is derived from “portray” which means to depict or represent something in a work of art. Using realistic proportions in portraiture helps artists accurately depict appearances. Images in this style are known as “representational art.” Jan van Eyck, Man in Red Turban, 1433. Skewing proportions is a method of accentuating certain features to enhance the subject’s expression. It adds interest and even humor and emotion to portraits but results in an unrealistic representation of the subject. Images of this kind are known as “igurative art” because they are modeled after real igures but are not meant to resemble them closely. When an artist makes an image of him- or herself, the work is called a “self-portrait.” Although people have been making selfportraits since the earliest times, it was not until the advent of readily-available mirrors of superior quality in the ifteenth century that the practice became common among painters and sculptors. The painting, Man in Red Turban, painted in oil on wood in 1433 by the Flemish painter, Jan van Eyck, is thought to be the irst self-portrait by a classical artist. While everyone agrees we each have a unique appearance, it is also true that every human face has proportions similar enough to base a standard template upon. Generally speaking, the human head is shaped like an upside-down egg. Imagine it drawn on a clean page. If you draw two horizontal lines to divide the egg in three roughly equal parts (with the top section slightly larger,) then you will have the lines and points upon which to place the main features of the face, the eyes, ears, nose and mouth. This is the beginning of a portrait. The mid-line of the eyes lies along the upper line. The top of the ear meets the upper line. The bottom of the ear meets the lower line. The mouth is half-way between the lower line and the bottom of the oval. The nose, of course, is placed in the centre of the oval between the two lines. Scott Hamilton, Madison Cary, 2012. Pencil on paper A great way to get to know facial proportions is to practise sketching faces. Sketching is a method of drawing quickly in order to study a subject and often, a whole series of sketches are produced in one sitting. This method allows artists to experiment with or record various perspectives, qualities of light, values and other elements that affect a subject. Sketching is also a useful skill to have when you need to jot down ideas, shapes and outlines. A sketch can be done in any drawing medium but is usually executed in pencil, charcoal or pastel. And while artists often regard sketches as practise for a inal piece, a sketch can also be a work of art on its own. Experiment with facial proportions to see if you can make a clownish face, a demonic face, an alien or a baby face. Once you discover how to make a good one, demonstrate how to make a bad portrait. But be kind. After all, you’ll be using your own face as the subject. A school photo of yourself or another tightly framed front view with eyes looking into the camera. Alternately, you can use a mirror and draw your reflection. Pencil Scrap paper for practise sketching Paper for self-portrait Masking tape 1. Carefully study the photo. Focus on the shapes and lines that you see. If you decide to make a igurative self-portrait, select a feature or features to accentuate in an unrealistic way. 2. Sketch a large, upside-down egg-shaped oval. Leave room at the sides for the ears. Leave room underneath for the neck and shoulders and some room at the top for hair. 3. Draw a faint vertical line through the middle of the oval. This is called the “centre line.” 4. Draw a faint horizontal line a third of the way down, even a bit more, from the top of the oval. 5. Draw a second faint horizontal line about a third of the way up from the bottom of the oval. 6. Sketch the facial features. Remember to draw ears and eyebrows. 7. Add the neck and shoulders and the hair. 8. Repeat. 9. When you are ready to make your self-portrait, begin by masking the edges of your paper with tape. This will reveal a clean, white border later on. 10. In your inal image, do not draw the faint proportion lines but keep them in mind as you work. Tips: The centre of the eye lines up with the corner of the mouth. The iris is half the width of the eye. Wrinkles appear when the eyes are open. The bridge of the nose begins at the brow. The upper lip is narrower than the lower lip. The line separating the lips is never straight. The hair never lays lat against the head. The neck begins at the bottom of the earlobes. 11. When you are satisied with your self-portrait, peel off the masking tape and sign your name in the bottom right corner. Get ready to share it. Show your works of art to each other and ask each other questions. 1. In what ways are your self-portraits and the images in Bad Portraits the same? 2. How do sketches differ from paintings? 3. With your new understanding, can you explain the terms, “representational art,” “igurative art,” “sketch” and “self-portrait?” 4. How does Mandy Stobo portray facial features? How do you portray facial features? “Rad” is short for “radical,” a word with several meanings. Used as an adjective, it describes core changes to something. It simply means “thorough” but it was revitalized in the 1990s in the popular vocabulary of one of the urban youth subcultures of the time. Cool and awesome people use “rad” to replace words like “cool” and “awesome” which we regard as overused. It also expresses amazement as in, “Rad portraits!” The student will: Make a portrait in the style of Mandy Stobo Be introduced to the basic concepts of colour theory Practise watercolour painting techniques Explore art as a method of expressing and evoking emotion Gain a new understanding of the paintings in Bad Portraits Like most works of art, the images in Bad Portraits have a way of stirring up emotions. You may already know that if you laughed or were bothered or felt sorry when you irst saw them. Art can affect the way people feel and to some degree, this phenomenon can be controlled with various elements of design, one of which is colour. Artists who understand the language of colour know it is a powerful portent of emotion. Colours help describe feelings. We often say someone is red with anger or green with envy and we speak of cheerful or depressing colours when we choose paint for interiors. And everyone knows a grey day can make a person feel blue. Artists use this common understanding and lots of other information about colour to imbue their works with feeling. Malaika Charbonneau, Utah, 2010. The notion of a theory of colours was irst explored by the ancient Greeks but in the early 1800s, a German poet named Johann von Goethe wrote a detailed book on the subject which would garner great interest in the next century, Zur Farbehlehre, (Theory of Colours.) Like theories of all kinds— theories of psychology and psychiatry, music theory, education theory—colour theory was embraced by visual artists in the 1920s, the same investigative era in which the art movement, Surrealism, emerged. Today, colour theory is comprised of a vast spectrum of information and ideas that range from scientiic studies of the properties of light and optics to cultural studies of the effect and meaning of colour. Some theorists are concerned with understanding colour in terms of the refraction of sunlight, (additive theory,) while others are concerned with understanding how to apply colour with paints, pigments and dyes, (subtractive theory.) It is interesting to note that while nearly three million colours have been identiied as refractions of light and the number is believed to be ininite, colours like brown and beige cannot be found in sunlight. On the other hand, no matter how hard humans try, we cannot seem to produce more than a few thousand colours of paint, hundreds of which are brown. While nearly every artist is concerned with colour and its effects on people, those who work with a brush take a special interest because they mix their own paints to make new colours every day. In the simplest terms, popular colour theory is based on the idea that three primary colours—most often identiied as red, yellow and blue—can be mixed in pairs to produce three secondary colours. From red, yellow and blue, you would get orange, green and purple and these six colours, in turn, can be mixed to produce tertiary colours. When all these colours are arranged in a circle to show an unending transition from red to orange to yellow, green, blue, purple and back to red again, the result is a colour wheel. Many artists consult a colour wheel of some kind, usually one of their own making, before they pick up a paint brush. A colour wheel showing primary and secondary colours and a colour wheel showing cool and warm colours Different combinations from the colour wheel create a variety of effective colour schemes and there are general rules to guide artists in their selections. Warm and cool In general, every colour on the wheel falls into one of two categories, warm or cool. Imagine the colour wheel divided to cut through the yellow-green and its opposite, the red-violet. The half that includes orange is comprised of colours that are regarded as warm while the half that includes blue is comprised of colours that are regarded as cool. For instance, just as an orange sun might appear to be a naturally warm object, an orange snowman can look warm in a work of art. Likewise, a blue lake might seem inherently cool but in art, a blue sun can have a perfectly believable cold look about it, too. Complementary colours Roberta Ross, Jammed, 2012. If you pair a colour with its opposite on the wheel, you will have complementary colours. The word, “complementary,” means to have the ability to make something else complete. Since complementary colours are far away from each other on the wheel, each is a mix of the colours the other lacks and therefore, together, they make a complete set of primary colours. Complementary colours provide strong contrasts in works of art. (The homonym, “complimentary,” means to have the quality of a compliment or kind words.) Analogous colours A selection of three colours in a row on the wheel is an analogous colour scheme. Analogous colours look agreeable and harmonious in works of art because they are either all warm or all cool. To add a bit of contrast, analogous colours are often balanced with one or two neutrals like black, white, grey, brown and beige or with one complementary colour. Colour triad “Triad” means a set of three. To ind a colour triad, start at any point on the colour wheel and draw a triangle with equal sides. The three colours at the corners of the triangle form the triad. Works which feature colour triads have an overall appearance of balance. Tints, shades and tones Artists mix their paints to achieve exactly the colours they have in mind. When a colour is made lighter by the addition of white, the result is called a “tint.” When it is made darker by the addition of black, the new colour is called a “shade.” A “tone” is what you get by adding grey to a colour. Tints have the effect of making objects appear close in the foreground while shades make objects seem to recede into the background. Tones are useful for changing the vigour of a colour. Artists use warm colours to evoke feelings of joy and vitality and cool colours to suggest serenity and solitude. Warm colours can impassion people and cool colours can chill us out. But with skill and understanding, colours can be altered and combined to make orange look dangerous and blue seem downright cuddly. Like Stobo has done with the works in Bad Portraits, you, too, can play with the colour wheel to ind ways to get rad reactions. A photo of a friend. Choose a tightly framed front view with eyes looking into the camera. The more expressive the image, the better. Marker Watercolour paper Watercolour paint Water Paint brush 1. Use a marker to draw the contours of your subject on the watercolour paper. “Contour” is another word for “outline.” Tip: Stobo says she squints when she looks at a subject to blur details and help her focus on contours. 2. Dip your wet brush in paint and use the following techniques to apply colour to your image. Wash Use a large, wet brush loaded with paint to apply the wash across the paper from left to right until the entire area is thinly covered. Blotting Blot the wash with damp paper towel to create a soft texture. Wet-on-wet Before it dries, paint on top of the wash to create blurred lines. Wet-on-dry After it dries, paint on top of the wash to create crisp lines. Dry brush Create broken lines by applying paint with very little water. Splatter Load the brush with paint and splatter the image for an unusual effect. 3. Share your rad portraits with family and friends by posting them on your favourite social media sites. Show your works of art to each other and ask each other questions. 1. In what ways are your rad portraits and the works in Bad Portraits the same? 2. Do your portraits express your feelings? Do they evoke emotions in others? 3. With your new understanding, can you explain the terms, “primary,” “secondary” and “tertiary colours?” Can you describe one or two colour schemes artists commonly use? 4. Do your colour schemes have the effect on viewers that you hoped for? 5. How do colours help artists express and evoke emotion? The student will: Be introduced to the concept of illustration Make an illustrated alphabet book Apply fundamental principles of art such as theme, shape, perspective and motion Explore illustration as a means of expression Gain a new understanding of the images in Bad Portraits In addition to painting images like the ones in Bad Portraits, Mandy Stobo also collaborates with other artists to produce works in different genres. She illustrates books, for instance, like the alphabet book, C is for Calgary. Most children’s books combine images and words to convey meaning. When images are designed to go with words in this way, they are called “illustrations.” And words and letters and numbers that appear along with illustrations are called “text.” Illustrations function as a decoration for text but they have a more important, less obvious role. They help people read by providing visual clues about the text. Some books can even be understood without being read because their illustrations contain so much information. And illustrations often show details that are absent from the text. Lynn Johnston, For Better or Worse, 2013. Just as writers use literary devices like imagery and onomatopoeia—“whap,” “bam” and “pop” are examples of onomatopoeia—to effectively explain ideas, artists use a variety of illustrative techniques. Shape, perspective, motion and humor are some of the basic elements of design that illustrators use to convey meaning. Shape Just as the shapes within an illustration affect its appearance and meaning, the overall shape of the illustration itself and the way it occupies the page have an inluence on readers, too. Full bleed: When the illustration ills the page from edge to edge. Border: When an illustration ills the page but leaves a space all around the edges. Spread: When an illustration runs across two pages. Some illustrations are orderly arrangements of a whole bunch of visual information or a sequence of events and these can take the shape of comic strips or ictitious maps. Perspective The word, “perspective,” is used to describe the place where the viewer imagines he or she is standing when looking at a scene. Another term for perspective is “vantage point.” Illustrators can use perspective to make you feel like you are sitting in a tree looking down at the world or loating on a raft looking up into the clouds. Motion Dramatic gestures and expressions communicate the actions and emotions in a story. Motion can be expressed by the posture of a subject and by the lines and squiggles surrounding a subject. Humour Funny details add interest to illustrations and engage readers. People always take a second look to make sure they caught all the visual jokes. One way to add humour is to draw things opposite to what is expected—babies sporting mustaches or animals wearing shoes. These alphabet books feature a spread, (left,) and a full bleed treatment, (right,) and include design elements like perspective, motion and humour. Artists use graphic information supplied by text as a starting point to inspire their illustrations. They expand on ideas that the words hint at and ill in the blanks that words cannot explain. Putting words and pictures together in a book is more than just an effective way to help readers understand. Illustration is a way of turning two good things into one amazing whole. Part 1: Writing Pencil Scrap paper for word list Paper for the book Part 2: Illustrating Coloured pencils and markers Scrap paper for sketching Ruler Part 3: Binding Card stock Coloured cord or ribbon Scissors Hole-punch Read C is for Calgary and note how the text and illustrations work together to convey meaning. Part 1: Writing 1. 2. 3. Choose a theme such as places, sports, foods, seasons, music—anything you like. It can be general like “animals” or speciic like “mammals of Alberta.” Decide on a title for your book. Keep it simple—most alphabet books have titles like The ABCs of Colour or The Rainbow Alphabet Book. The title will appear along with your name on the cover as well as on the title page inside the book. List all the letters of the alphabet on paper. Tip: To adapt the project for a shorter time frame, list just the vowels or just the letters, “A,” “B” and “C,” for example. Or use numbers or the letters in your name. 4. Think up words related to your theme. Use each letter as an initial and list the theme words beside the alphabet. Tips: For dificult letters like “Q” and “Z,” use words that contain them instead of begin with them. If the theme is colour and you can’t think of anything that starts with “Z,” use the word, “azure.” Use words speciic to your theme but also remember to use a few general words like “between” for the letter, “B,” and “under” for the letter, “U.” This can add interest and even humour—and will be helpful if you get stuck on a letter. 5. Count the pages of your book and assemble the right number of sheets of paper in a stack. Tips: Decide whether to put one alphabet letter on each page or two or more. Decide whether to use both sides of each page or just one side. Include a sheet for the title page as well as two sheets for the lyleaves, blank pages which appear inside the back cover and at the front between the cover and title page. 6. Add to the stack two pieces of card stock, one for the front cover and one for the back. Part 2: Illustrating 1. On scrap paper, sketch illustration ideas. The drawings should explain, exemplify or otherwise refer to your theme words. Fit the images, alphabet letters and theme words together. Tips: Choose a colour scheme—see Lesson 2 Colours are Rad for easy tips on how to do that. Try hiding the text in the illustrations. Practise different types of lettering. If you want all the pages to be the same in a certain way—with the alphabet letter capitalized or lower-case, centred or off-centre, or if you want the same background colour throughout the book, for instance—decide now during the practise stage. NOTE: Before you proceed, remember to leave an inch-wide margin at the edge of each page where the hole-punch will cut a bit of paper away and the crease will hide part of the page. 2. Pencil in the alphabet letters, theme words and title-page information on the assembled pages. Tip: With a ruler, draw a faint line where you want to put a theme word and print neatly along it. 3. Draw the images. 4. Colour the pages with pencils and markers. Remember that leaving certain areas uncoloured is an effective technique, too. 5. Outline the alphabet letters in black marker to add emphasis and unify the pages. Go over the letters of the theme words with black marker to get the same effect. 6. Write the title and author on the front cover and decorate it. Use the black marker as you did in Step 5. On the back cover in small printing, write the year and the name of your city or town or school. Part 3: Binding 1. Double-check the order of the pages and covers. 2. Punch holes in two, three or ive places depending on the size and rigidity of the paper. If you use a single hole-punch, measure and mark the holes accurately. 3. Cut lengths of coloured cord or ribbon and use them to tie the pages together. 4. Read and enjoy. Now get ready to share it. Show your alphabet books to each other and ask each other questions. 1. In what ways are your books and the book, C is for Calgary, the same? 2. How do illustrations differ from other works of art such as the images in Bad Portraits? 3. Do your drawings explain or exemplify your theme words? How did you do that? 4. With your new understanding, can you explain the terms, “text” and “theme,” “full bleed” and “spread?” 5. When artists like Mandy Stobo draw an illustration, where do they begin? How do you begin an illustration? The student will: Be introduced to the concept of collaboration Practise working with others to create works of art and establish an online gallery Explore the visual arts as a means of staying active and involved Learn about promoting art by using social media web sites Gain a new understanding of the images in Bad Portraits Mandy Stobo is a painter but if you are picturing a quiet lady alone at an easel on a remote hillside, you are way off base. Stobo is an urban artist who is eager to collaborate on new works and invent new ways of making art. And while she does use traditional art venues like galleries and exhibitions to present her works, her greater focus is on social media. She uses it to promote her art business, showcase her solo and collaborative creations and meet fabulous people—subjects, clients, patrons and collaborative artists like herself. The images in the exhibition, Bad Portraits, demonstrate Stobo’s sensitive interest in people and her not-so-sensitive appreciation of their uniqueness. She maintains this sincere interest and honest appreciation in her working relationships with artists and others and as a result, has become a collaborator extraordinaire. The word, “collaborate,” is made up of the preix, “co,” which means “with” or “together” and the root, “labor,” which means “to work.” Stobo has worked together with other people to develop a range of art products including a book, CDs, videos, works of public art and music events, as well as art-based web sites. Not Mandy Stobo Collaborations always start with one person who has the courage to share an idea and reach out for help developing it. Yet it has been said that a real leader is not necessarily the one who comes up with the idea but the irst one who declares support for the one with the idea. When these two collaborators invite others to contribute to a project, everyone gets absorbed in the work and it no longer seems to matter whose idea it was in the irst place. Tibetan monks collaborating on a mandala Stobo has collaborated on conventional projects such as working with the children’s author, Dave Kelly, to illustrate an alphabet book titled C is for Calgary but she has also worked on projects that are entirely experimental. She participated in a weekly music event called Record 1235 that invited musicians to set up their amps and instruments in an art studio and play while she painted. They all wanted to see how the music would inluence the painting and how watching the images materialize would inluence the band’s sound. At the end of each session, they pressed one hundred albums, produced a video and posted excerpts of everything online. Neil Zeller, Mandy Stobo at MB Fitzgerald Concert, 2013 Collaboration doesn’t always involve other artists. Sometimes, like in the Bad Portraits Project, the collaboration is between the artist and members of the public and it takes the form of a service Stobo provides. She posted a request for personal pictures on her website along with the entreaty, “You send me your picture and I make you bad.” The portraits in the exhibition are all based on the submissions she received in response to that post. One of her most innovative business ideas is live painting at events. She rents herself out as a sort of wedding photographer except it isn’t usually a wedding and she doesn’t take photos but paints the guests and venue instead while people look on. At the close of the event, the painting is auctioned off and the proceeds are donated to charity. She also does another version of live painting where she designs a work of art for a client, usually someone from the corporate sector, who then invites guests, usually colleagues, to a painting party where Stobo guides them in using the brushes to create their own original collaborative piece. Mandy Stobo, Grate Self-portrait, 2012. Photo courtesy of the artist Another way Stobo collaborates is by making public art. This sometimes involves collaborating with artists but more importantly, is an example of how artists can work with public oficials to increase awareness of art and beautify the urban environment. She added colour and humor and interest to Calgary’s downtown core with the Grate Portrait Project, a campaign of painting portraits on the ground-level steel grates that surround the trees on vibrant Stephen Avenue. All of the products of her collaborations are posted on Stobo’s web site, mandystobo.com, and she has web sites for special projects, too, like badportraitproject.com. She promotes her art and collaborations on social media sites like Facebook and Twitter and hosts exhibitions and attends art events of every kind. So if you were thinking, the most active an artist ever gets is when she dips her paint brush in water, think again. Art is an awesome way to connect with collaborators and clients, contribute to the community and to charitable causes, promote awareness, provide a service and earn money— for more art supplies. People Paper and pencil for each collaborator Digital camera Computer Collaboration Station 1—a meeting place. It can be a table or a carpet or a patch of lawn, any location that is comfortable for everybody and conducive to easy communication. Collaboration Station 2—a virtual meeting place. It can be a Facebook page or a blog and will serve as an online art gallery. You might even choose to tweet art to your Twitter followers—and those you want for followers. Stobo tweeted unsolicited portraits of celebrities to their Twitter accounts and got awesome responses from people like George Stroumboulopoulos, Conan O’Brien and Jimmy Fallon. Collaborate and make your own instructions. Keep notes of your meetings and make a list of the tasks you take on. Consider all the extraordinary collaborations Stobo has worked on and think about the kind of collaboration you want to be involved in. You can make public art, art to raise funds for charity, art to promote a cause or just to enjoy among yourselves. You can make art in any genre and by combining genres—painting, drawing, literature, music, anything you want. Start your collaboration by inding out who among you has an art idea that everyone can work on. Who among you will be the irst to support the person with the idea? Tips for working with others: Be kind. Sometimes, a hasty remark can make people close up even when no one means that to happen so pause before you speak. Include everyone. Consider every idea. Take turns contributing so talkative people don’t overshadow quiet people. Take notes instead of interrupting and respond when the time is right. Make it your responsibility to ensure that each member of the group is happy with every decision. Prepare to speak up and ask for what you want. Expect to compromise. Tips for making art and establishing an online gallery: Make a plan. Gather materials. Create art. Set up a Facebook page or something similar. Take photos of your works and post them at your online art gallery. Arrange your next collaborators’ meeting. Involve others. Involve the community. Consider approaching local oficials with an idea for public art in your community. Start a campaign to beautify your environment or promote a cause. Demonstrate how art keeps people active, socially and creatively. 1. What kind of art did you produce by collaborating with others? How are they the same as or different than the collaborations Mandy Stobo participated in? 2. How did your collaborative works of art turn out? Are they as successful as you hoped? 3. What has this experience taught you about yourself, about others, about art? 4. How were you inluenced by others in your group? How did you inluence them? 5. What are you going to collaborate on next? The student will: Paint an unbalanced character in the style of Mandy Stobo Be introduced to the concepts of balance and symmetry Apply fundamental art techniques like painting with watercolours and gouache Explore methods of adding interest and expression in portraiture Gain a new understanding of the paintings in Bad Portraits The twenty-four paintings in the exhibition, Bad Portraits, are, by deinition, images of people’s faces. And people’s faces are, by deinition, pretty much the same on both sides, with even and equal features and noses centred right in the middle. Yet Mandy Stobo seems intent on portraying us as unbalanced. When an object has the quality of being the same on both sides, it is said to have “symmetry” or be “symmetrical.” The word is derived from the preix, “sym,” meaning “together” or “with,” and the root, “metre,” which means “measure.” The faces of all the animals in the animal kingdom—except a family of ish called “lounders”—are symmetrical as are nearly all the leaves and lowers in the plant kingdom. You can tell if something is symmetrical by drawing an imaginary line down the middle of it. If each half is a mirror image of its opposite, the object is symmetrical. The topiaries illustrate symmetry and the cottonwood tree illustrates asymmetry. When each half of an object is different from its opposite, the object is “asymmetrical” or is said to lack symmetry. The preix, “a,” means “not” or “without.” In nature, trees, rocks, clouds and mountains are usually asymmetrical. It looks weird when they are not. Bill Reid, Beaver Bracelet, 1962. Artists use symmetry to achieve realism and to add balance to their works. Some works possess a meditative and harmonious quality as a result of their uncanny symmetry. Designers of threedimensional and functional art like jewelry and furniture use symmetry extensively. But when artists wish to add interest and a sense of conlict or excitement to their images, they employ asymmetry. Imagine twenty-four portraits with subjects centred in the frame and wearing the same colours—it would look more like a yearbook than art. Unless you expect to recognize someone, your eyes will just glaze over such portraits from lack of interest. Symmetry and realism are predictable while asymmetry adds surprise, even humour, and allows the artist to present the subject in an original and interesting way. The challenge facing the portrait artist is to maintain the natural symmetry of the human face while creating an overall appearance of asymmetry in the image. Stobo does this a number of ways. Composition In some of Stobo’s works, the main element or elements are not centred on the page but placed off to the side to disrupt the balance. This is asymmetrical composition. The word, “compose,” is derived from the preix, “com,” which means “together” or “with,” and the root, “posit,” which means “to place” or “put.” Colour Stobo uses bands and clouds of colour to create asymmetry. The complexions and shadows in her portraits also feature colour combinations that disrupt the natural balance of the facial features. See Lesson 2 Colours are Rad for an explanation of common colour schemes. Stobo chooses watercolours as the medium for adding colour because they are transparent and transparency is conducive to visual movement. The coloured elements in her portraits have a quality of being in motion. Black Stobo uses black gouache to anchor the eye on certain elements of her work. Gouache is a water-based paint but quite different from watercolours because it contains a chalky substance that makes it opaque. While the word, “transparent,” means “able to be seen through,” “opaque” means the opposite, “unable to be seen through.” Tea, for example, is transparent and milk is opaque. The black elements in Stobo’s portraits have a quality of being stationary or unmoving. They arrest the eye. Stobo uses black gouache for facial contours, feature contours, eyebrows, irises, wrinkles and dimples. Accessories Many of the subjects in Bad Portraits are wearing fashion and sports accessories that reveal their personalities—a helmet, a loppy hat, spectacles, earrings—and these items are often the source of asymmetry in the images as well. The helmet reaches beyond the edge of the frame, the hat takes up half the surface area, the glasses are too big for the face and the earrings draw the eye down and around the composition. One fellow looks symmetrical enough but is completely overpowered by an outlandish headpiece and goggles. Facial features A boy’s front teeth are portrayed as crooked white rectangles in an uneven smile. A girl’s throat is painted blue to suggest shadow. Some faces feature irregular blotches and splatters, some have one eye bigger than the other or eyebrows of different colours. These are all techniques that have the effect of throwing the images off balance. Anatomy Stobo adds gesturing hands, turning necks, hunched shoulders, big hair, no hair and other body parts to add motion and shape, both of which contribute to asymmetry in her works. Expression Some subjects are depicted with mouths wide open in laughter or conversation. Some look directly at the viewer while others focus on something else outside the frame and cause the viewer to wonder what is there. One subject has her head tilted back in a smile and another looks down and shrinks from what he sees. Examine the paintings in Bad Portraits. Each one looks a lot like a real character, someone with an amazing personality, but not one of the images emphasizes the natural symmetry of the human face. Ironically, by incorporating asymmetry in her paintings, Stobo succeeds at realistically portraying the most interesting feature of these characters, their natural expressions. It’s as plain as the nose in the middle of your face. Portrait—a school photo, family photo or magazine image—any tightly framed front view Paper Pencil Scrap paper for practise sketching Watercolour paper Watercolour paints Black gouache Water Paint brush Masking tape 1. Carefully study the photo. Note the shapes and lines that you see. Think about what you can add to throw the image off balance. 2. Select one or more techniques for incorporating asymmetry in your image: composition, colour, the use of black, accessories, facial features, anatomy, expression. 3. Practise sketching the face and itting in the asymmetrical elements. Focus less on making a likeness of the photo and more on making the overall image interesting. For tips on sketching the human face with realistic proportions, see Lesson 2 Colours are Rad. 4. Repeat. 5. When you are ready to paint your unbalanced character, begin by masking the edges of the watercolour paper with tape. This will reveal a clean, white border later on. 6. Pencil in the main contours of the image. 7. Dip your brush in water and start painting bands and clouds of colour. See Lesson 2 Colours are Rad for a summary of common watercolour techniques. 8. When the watercolours are dry, dip a clean brush in water and apply the gouache to the elements you wish the eye to rest on. 9. When the gouache is dry, peel off the masking tape and sign your name in the bottom right corner. Get ready to share your art. Show your portraits to each other and ask each other questions. 1. In what ways are your unbalanced characters and the images in Bad Portraits the same? 2. With your new understanding, can you explain the terms, “symmetry” and “asymmetry,” “transparent” and “opaque?” 3. How did you incorporate asymmetry in your portraits? 4. How do watercolours and gouache differ? How are they used? What effects do they produce? 5. How does Mandy Stobo add interest to her portraits? How do you add interest to portraits? Special thanks to those who have contributed to the success of this TREX publication: Joanne Marion, Director/Curator, Art Gallery, Esplanade Arts and Heritage Centre Joanne Ellis, Gallery Assistant, Esplanade Arts and Heritage Centre Saira Lachapelle, Acting Program Manager, TREX Region 4, Esplanade Arts and Heritage Centre Samantha Kelly, Art Collection Consultant, Alberta Foundation for the Arts Gail Lint, Art Exhibition Consultant, Alberta Foundation for the Arts Neil Lazaruk, Art Preparator, Alberta Foundation for the Arts Lee Anne Charbonneau, Writer and Editor Biography Jeremy Fokkens, Mandy Stobo, 2013 http://jeremyfokkens.com/ blog/?p=823 & www.jfphoto.ca Lesson 1 Sketch Yourself Jan van Eyck, Man in Red Turban, 1433 http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/jan-vaneyck/a-man-in-a-turban-1433 Lee Anne Charbonneau, Facial Proportions, Original Illustration, 2013 Scott Hamilton, Madison Cary, 2012 http://artboy68.com/100portraits.html Lesson 2 Colours are Rad Malaika Charbonneau, Utah, 2010 http://www.thestallgallery.com/malaika-zbesheskicharbonneau.html Colour Wheel Primary and Secondary, Illustration http://www.catspitproductionsllc. com/screen-printing-ink-mixing.html Colour Wheel Warm and Cool, Illustration http://www.tigercolor.com/color-lab/colortheory/color-theory-intro.htm Roberta Ross, Jammed, 2012 http://www.thestallgallery.com/roberta-ross.html Lesson 3 The ABCs of Making an Alphabet Book Lynn Johnston, For Better or Worse, posted and retrieved July 25, 2013 http://fborfw. com/strip_ix/2013/07/thursday-july-25-2013.php Graeme Base, Animalia, 1990 http://ourpace.blogspot.ca/2012/05/book-sharing-mon day-animalia.html Jerry Pallotta, The Vegetable Alphabet Book, 1992 http://lookingglassreview.com/html/ alphabet_books.html Lesson 4 Collaboration Station Painter at Easel, Photo http://www.etsy.com/listing/31815127/artist-easel-painterseasel Neil Zeller, Mandy Stobo at MB Fitzgerald Concert, 2013 Photo courtesy Neil Zeller Photography Tibetan Monks at Mandala, Photo http://www.kunstpedia.com/articles/beneath-themask-further-thoughts-on-african-art-and-the-western-imagination.html?page=9 Mandy Stobo, Grate Self-portrait, 2012 Photo courtesy of the artist Lesson 5 Unbalanced Characters Topiary, Photo http://hydrangeahillcottage.blogspot.ca/2011/05/english-topiary-eyecandy.html Mike Heller, Cottonwood Tree, Photo http://photokaz.com/2012/08/a-visit-to-alberta/ Bill Reid, Beaver Bracelet, 1962, Photo http://pegasusgallery.ca/artist/billreid.html Amyotte, Nicolle. “Local artist paints ‘bad portraits’ of Calgarians,” Calgary Journal, November 29, 2012. Web. Retrieved July 15, 2013, at http://www. calgaryjournal.ca/index.php/calgary-arts/meet-the-artist/1270-local-artistpaints-bad-portraits-of-calgarians Arts Avenue, “Bad portraits are good!” March 26, 2012. Web. Retrieved July 15, 2013, at http://artsavenue.ca/theavenue/2012/03/bad-portraits-are-good/ Brynjolson, Rhian. Art and Illustration: A Guide for Teachers and Parents. Winnipeg: Peguis Publishers. Print. 1998. Brynjolson, Rhian. Teaching Arts: A Complete Guide for the Classroom. Winnipeg: Portage and Main Press. Print. 2009. CBC News, Bad Portraits: Calgary’s ‘grate’ new walk of fame. Sept. 13, 2012. Web. Retrieved July 15, 2013, at http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/calgary/ story/2012/09/13/calgary-mandy-stobo-bad-portraits.html Chimwaso, Inonge. The Weal, “Ugly is Beautiful.” Web. January 25, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2013, at http://www.theweal.com/2013/01/25/ugly-is-beautiful/ Davis, Anthony A. Macleans, “Bad portraits done good.” Web. November 23, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2013, at http://www2.macleans.ca/tag/mandy-stobo/ Horowitz, Elizabeth. Watercolor: A Beginner’s Guide. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. Print. 2006. Joosten, Tanya. Social Media for Educators: Strategies and Best Practices. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Print. 2012. Kleiner, Fred S. et al. Western Perspective, Volume II, “Gardner’s Art Through the Ages.” Print. 2006. Market Collective, “Mandy Stobo.” May 6, 2013. Web. Retrieved July 15, 2013, at http:// www.marketcollective.ca/artist-mandy-stobo/ Ocvirk, Otto G. et al. Art Fundamentals, Theory and Practice. Bowling Green State University: McGraw-Hill. Print. 2006. Schminke, “Gouache and Tempera: A Short Guide.” Nurtingen: Schminke and Company. October 24, 2005. Web. Retrieved August 5, 2013, at http://www. schmincke.de/uploads/media/Gouache_and_Tempera_11_2005.pdf Schwake, Susan. Art Lab for Kids. London: Quarry Books. Print. 2012. Seto, Irene. Calgary is Awesome, “DIY: Mandy Stobo makes bad so rad.” Web. July 10, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2013, at http://calgaryisawesome.com/2012/07/10/ diy-mandy-stobo-makes-bad-so-rad/ Webtrends, What is Social Media? Web. Retrieved July 22, 2013, at http://webtrends. about.com/od/web20/a/social-media.htm © 2013 by the Esplanade Arts and Heritage Centre, Medicine Hat, Alberta. The Esplanade Arts and Heritage Centre retains sole copyright to its contributions to this book.