URN_NBN_fi_jyu-20

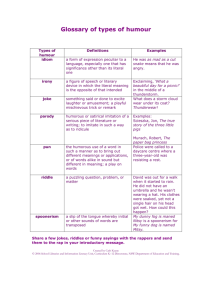

advertisement