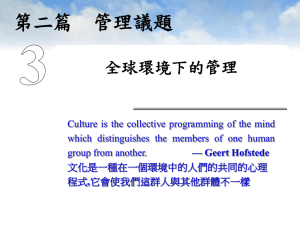

Geert Hofstede et al's Set of National Cultural Dimensions

advertisement