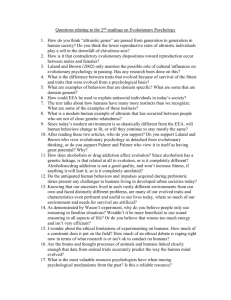

Evolutionary Origins of Leadership and Followership

advertisement