A theory of inhaled anesthetic action by disruption of ligand diffusion

advertisement

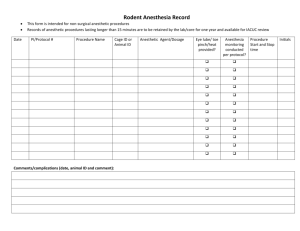

A theory of inhaled anesthetic action by disruption of ligand diffusion chreodes Lemont B. Kier, PhD Richmond, Virginia A theory is proposed for the clinical actions and behavior of volatile anesthetic agents. Evidence supports the nonspecific and ubiquitous effects of these drugs in which many ligand-receptor systems may be involved. The volatile anesthetic drugs interfere with the diffusion of ligands to receptors across the hydrodynamic landscape on the protein surface. The hydropathic states of the amino acid side chains on the landscape of an active site influence the water to form evanescent paths, called chreodes as defined by T he mechanism of action of inhaled anesthetic agents has been considered for more than a century and is summarized in recent reviews.1,2 The earliest contribution to the mechanism of these drugs came at a time before there was any understanding of the chemical nature of cell membranes or proteins. It was observed that there was a notable correlation between potency and the solubility of the drug in olive oil.3 When the lipoidal nature of cell membranes was recognized, a formal mechanism was proposed wherein inhaled anesthetic drugs produced their effect by entering and altering, in some way, the normal function of these structures.4 The consequences of this alteration were assumed to have an impact on the proteins imbedded in the membrane. Some effects of inhaled anesthetics on membranes have been noted, but they require concentrations well above clinical levels.5,6 Recently, the observation that stereoisomers of anesthetics such as isoflurane exhibit a modest but real difference in potency casts doubt on the cell membrane lipid bilayer being the target.7,8 An alternative mechanism invokes an induced lateral pressure on the phospholipid-water boundary created by the presence of anesthetic molecules in the membrane.9,10 The presence of anesthetic molecules may disrupt the interface between the bilayer molecules and the imbedded proteins, altering their function. Another focus of attention has been on proteins as targets of inhaled anesthetic drugs. One observation that stimulated this consideration was the correlation between anesthetic potency and the inhibition of the enzyme luciferase.11 The concentrations needed for clinical effectiveness, however, do not support the concept of a receptor on a protein as the target of an 422 AANA Journal/December 2003/Vol. 71, No. 6 Waddington and offered as an appropriate term by Kier. These chreodes are altered by the presence of volatile anesthetic drugs, leading to a reduction in the diffusion of many ligands to their active sites. This effect is sufficient to decrease the responses of these receptors, leading to an anesthetic state. Key words: Inhaled anesthetics, ligand diffusion, mechanism of action, protein landscape, water chreodes. anesthetic molecule.12-14 There is no evidence of high affinity binding, characteristic of a specific ligandreceptor encounter. Indeed, inhaled anesthetic molecules alter the function of many receptors, enzymes, transporters, and structural proteins.14 The interaction of anesthetics with certain receptors has come under study. In particular, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) has been studied and the profile of response documented.15,16 The behavior of GABA receptors does not conform to what is observed clinically in the presence of anesthetics.17-20 As an alternative, the involvement of multiple binding sites, one for each drug, on the same target has been postulated21,22 and supported by some studies.23,24 The evidence for multiple binding sites also comes from the observation of a steep dose-response relationship,25 characteristic of low variability of responsiveness. The responsiveness to anesthetics is ubiquitous among mammals, and even plants.26 Tolerance is not common with anesthetics, an attribute expected of drugs acting at specific receptors. A general view emerges from these studies that relatively weak binding, not characteristic of a specific drug-receptor encounter, is occurring to produce the anesthetic effect. One idea supporting this view is that cavities on proteins are targets of anesthetic molecules, disrupting their normal function.27,28 To summarize, the current level of wisdom on the mechanism of inhaled anesthetics points to small encounters at many sites on a protein, most likely not at the receptor on its surface.1,2 This conclusion relates to our recent studies of the landscape around receptors on proteins and their role in facilitating ligand diffusion to the receptors.29 This report will reveal the significance of that work and a postulate of an inhalation anesthetic mechanism that arises from it. A theory of ligand diffusion across a protein landscape • Background. An early view considered the approach of a ligand to be through bulk water to a target site. A 3-dimensional random walk throughout the entire approach is now postulated to be too slow to permit coordination of the heterogeneous complex processes in living systems.30 A current view considers some period of residence of the ligand near the surface of a protein on the way to an encounter with a target site. The central idea is that the approach of a ligand to a target site is a process assumed to be 2-dimensional diffusion, acting as a facilitating condition for the ligandreceptor events. This diffusion has been the subject of a number of studies and models over the years. Several models of a 2-dimensional passage on cell and protein surfaces have been described. A model by Hasinoff describes the nonspecific binding of a ligand to the charged surface of an enzyme.31 The ligand then follows a 2-dimensional walk to the active site. This effectively increases the size of the target on the enzyme. A model by Chou and Zhou describes an enzyme molecule with multiple receptor sites.32 A ligand molecule encounters the enzyme surface and diffuses to a nearby receptor to initiate the reaction. The expectation of a significant accumulation of ligands on the enzyme surface is an outcome of the calculations based on this model. The entire surface of the enzyme is regarded as a “sink” where the ligand diffuses to an active site. The conclusion was drawn that amino acid side chains outside of the active site play a major role as “promoters,” facilitating a rapid diffusion to the active site. The participation of the water near the protein surface was discussed by Welch who theorized that the microviscosity of near water was influential on the rate of catalytic reactions.33 The possibility that the viscosity of water near the protein surface is significantly higher than bulk water creates an ordering in a layer that might facilitate faster diffusion of a solute near the protein surface. A functional model was proposed by Birch and Latymer who did not specify the nature of the ligand approach to the receptor but described a model of the residence of several ligands near the active site.34 An experimental observation was made that upon administration of sweet-tasting molecules to observers followed by a washout of the compound, a persistence of the sweet taste results. Birch and Latymer considered several possible models including a nonspecific localized pooling of the compound in the vicinity of the receptor. Based on experimental work they proposed a model in which the sweet molecules are located in a queue organized near the surface of the protein. After washout, the molecules are retained in the queue, and so they continue to move toward the receptor, activating it as long as the queue is occupied. When the queue is empty, the sweet taste vanishes. This model invokes a directional effect focused on the receptor as well as the possibility of sustained residence of several molecules near the receptor. In summary, experimental and modeling evidence may be interpreted as describing a facilitation of reaction rates and receptor activation due to the rapid diffusion of ligands to target sites in essentially a 2dimensional domain. This diffusion most likely occurs near the surface of a protein involving water and structural features not part of the target site. The forces guiding the ligand to the target site would be expected to result in several effects. These include some period of retention on the protein surface and some influence directing the ligand to the target site. These considerations and the demonstrated role of water lead us to consider a model involving the immediate layers of water enshrouding the protein. • Chreodes. We have recently proposed that ligand molecules encounter the surface of a protein molecule and are captured within the first few layers of water on the surface.29 They are then guided to the active site over a series of evanescent cavity paths created by the relative hydrophobic effect responding to the hydropathic state of each amino acid side chain. These paths are preferences reminiscent of the chreodes envisioned by Waddington in his description of preferences on an epigenetic landscape.35 The word “epigenetic” was coined from the Greek words for “necessary” and “route” or “path.” He defined it as a representation of a temporal succession of states of a system. That system is characterized by a property with ingredients in the system that tend to respond to perturbations by preferring a presence in the chreode. Because this definition is close to the dynamic character of the paths created by the hydrophobic effect of the field of surface side chains, we have adopted this term to characterize the system in our model. A number of attributes are associated with the chreodes proposed in this report that have an impact on diffusion events that they influence. These chreodes are distinct for each type of receptor (or enzyme active site). This arises from the fact that the landscape of amino acid side chains around a receptor is just as defined as the receptor itself. The landscape is therefore an extension of the receptor with some degree of specificity. This is true because the pattern of amino acid side chains in the landscape is reproducible from one specific receptor protein to the next, just as is the receptor itself. In a sense, when we speak AANA Journal/December 2003/Vol. 71, No. 6 423 of a receptor, we should be including the landscape as a part of the whole. The chreodes created in the landscape of a receptor are invoked to account for a facilitated diffusion of a ligand to that receptor. It is possible that the exiting of a ligand from the receptor may be facilitated by another set of chreodes. A second attribute of these chreodes is that they are evanescent, constantly coming into existence, fading, and returning. They exist only as a “most probable” pattern of passages through water. Collectively, and over time, they meet the definition of a chreode (discussed above), always returning to a pattern favoring a directed and facilitated diffusion influence. A third attribute is found in the detailed structure of each chreode, governed by local patterns of amino acids, their hydropathic states, and their topology. The arrangement of amino acids on a protein is such that there would be a size and structure limitation for a molecule traversing the chreode. This is expected since the surface side chains are relatively close to each other and because the water structured by their hydropathic states is only 2 or 3 molecule layers out from the protein surface. The protein structure has evolved along with the ligand specific for a receptor on its surface. Therefore the specific ligand for the receptor experiences an optimal relationship with the chreode. The local structure and topology of segments of a chreode present to surrounding bulk water asymmetric patterns of side chains. The consequences of this are a different orientation and binding affinity of each segment to chiral isomers captured within the segment. This effect translates into a possible stereoselectivity Figure 1. A cellular automata model of a protein surface with randomly placed amino acid side chains S C C D D B E B C D D B E B C C A C D C B D A D A C D B B D A C B A D A A C E A B D C E B E C B A C E C A D © A B E B B C A C A C E A C D C C A B D A E C B A D A D A B B A B A C B C A C A D B A E A C The letters depict a particular polar state of the side chain. The letter A stands for a polar side chain, while the letter E stands for a nonpolar side chain. The letters B, C and D encode intermediate degrees of polarity. These side chain models are stationary. The surface is bathed with water molecules, not shown, that move over the surface, interacting in a characteristic way with each side chain. A ligand molecule, S, is allowed to diffuse throughout the system, responding to the influences of the side chains on the water molecules. The dynamics are run until the S molecule contacts the receptor, the heart, in the center of the grid. The heart,©, is the target of the ligand, S, in its diffusion across the protein surface. The average rate of this diffusion is calculated over many runs. 424 AANA Journal/December 2003/Vol. 71, No. 6 Figure 2. A cellular automata model of a protein surface with organized placement of amino acid side chains to create a chreode S C C D A B E B C D D B E B B C A C D C B D A D C C D B B D A C B A D A A C E A B D C E E E C B A C B C D E © E D C B A C A C A E E A C D C C A B D D E C B A D A D A B C A B A C B C A C A B B A E A C This figure is the same as Figure 1 except that the side chains are not randomly placed but are organized to create chreodes focused on the receptor. The dynamics are run as before with the average diffusion time recorded. The underlined letters are the side chains that constitute the chreodes. The heart,©, is the receptor. It is the target of the ligand, S, in its diffusion across the protein surface. associated with each segment of a chreode. The sum of these effects along the chreode may result in a modest stereoselectivity manifested before the molecule reaches the receptor. The credit for stereoselectivity has traditionally been ascribed exclusively to the receptor. A final attribute of the chreodes is their potential fragility in the presence of other molecules that are of optimal size and hydropathic state. Such molecules may enter, interfere with, and disrupt the structure of the chreode at any segment along their path. Just as the amino acid side chains are the source of the hydrophobic effect creating the chreodes, so another optimally structured molecule may reorganize the water near the protein surface to create a “nonchreode” pattern. This would have some effect on the diffusion of the specific ligand associated with that receptor and its chreode system. In our study of chreodes created by protein surface amino acid side chains, we modeled the effect of chreodes using cellular automata dynamics.29 This study was conducted using a simulated surface with a random distribution of side chain models. A model simulating the absence of any chreode pattern, shown in Figure 1, led to an average diffusion rate of a ligand model to be about 3.1 ¥ 10-3 cell spaces per iteration. A pattern of side chains was then modeled, creating a chreode that is focused on the receptor (Figure 2). The average rate of diffusion of a ligand was found to be 4.5 ¥ 10-3 cell spaces per iteration. These results were part of the evidence used to construct the theory of ligand passage to a receptor via chreodes in water that are organized by the surface amino acid side chains.29 In a second study, we have repeated these simulations and have modified the simulation containing the chreode pattern36 (see Figure 2). In this case we have introduced a number of solute molecules in addition AANA Journal/December 2003/Vol. 71, No. 6 425 Table 1. Comparison of molecular volumes (V) of amino acid side chains and volatile anesthetic drugs Side chain 3 V (cm /mole) Tryptophan Arginine Tyrosine Phenylalinine 80 69 64 56 Lysine 51 Glutamine Methionine Leucine Isoleucine Glutamic acid Histidine Asparagine Valine Aspartic acid Serine Threonine Cystine 46 45 45 45 43 36 36 36 33 27 25 25 Alanine Glycine 14 3 Anesthetic Sevoflurane Methoxyflurane Enflurane Desflurane Halothane Isoflurane Ether 69 66 63 57 57 53 52 Chloroform 45 Nitrous oxide to the ligand. It was found that the additional molecules interfered with the diffusion rate. The rate of diffusion of the ligand was reduced to 3.0 ¥ 10-3 cell spaces per iteration. The presence of the modeled solute molecules interfered with the chreodes, thereby reducing their influence on the diffusion process. This model, along with the other evidence described, has led us to propose a general theory of the action of the inhaled anesthetics. A theory of volatile anesthetic mechanism The current mechanistic view of weak encounters of volatile anesthetic molecules at many sites on or near protein surfaces appears compatible with the theory of chreodes facilitating and directing ligands to receptors (or enzyme active sites). Each system of chreodes associated with a receptor has its own structure, which is governed by the landscape of side chains. Each dynamic system of chreodes has evolved to accommodate a specific ligand. The chreodes are formed by water molecules and hydrogen bonding in 426 3 V (cm /mole) AANA Journal/December 2003/Vol. 71, No. 6 3 Alkane V (cm /mole) Decane Nonane Octane Heptane Hexane 109 99 88 79 68 Pentane 58 Butane 48 Propane 38 Ethane 27 Methane 17 19 places and forming cavities in other places in response to the relative hydropathic states of surface side chains. This phenomena has been demonstrated by the orientation effects of nonpolar solutes studied by vibrational spectroscopy37 and the flickering, fluctuating pattern of water and cavities observed between close polar and nonpolar surfaces, which are revealed by shear measurements.38 Inhalational anesthetic molecules have sizes approximating those of amino acid side chains (Table 1) and lipophilicities approximating those of the lipophilic side chains (Table 2). These 2 molecular properties are most influential in controlling the creation of the hydrophobic effect. Thus their presence in or near a chreode could alter the original pattern, thereby disrupting the normal diffusion of the ligand to the receptor. This effect depends upon a significant concentration and would vary in its intensity from one receptor-chreode complex to another. Because of the diversity of landscape structures associated with different receptors and the differences among the Table 2. Comparison of octanol/water partition coefficients (Log P) of lipophilic amino acid side chains and volatile anesthetic drugs Side chain Tryptophan Log P 2.25 Isoleucine Phenylalanine Leucine Cystine Valine Methionine 1.80 1.80 1.70 1.54 1.23 1.23 Tyrosine 0.96 Alanine Threonine Histidine 0.31 0.26 0.13 Anesthetic Log P Alkane Log P Heptane Hexane 3.5 3.0 Sevoflurane 2.34 Pentane 2.5 Methoxyflurane Enflurane Isoflurane 2.21 2.10 2.06 Butane 2.0 Desflurane Halothane 1.80 1.70 Propane 1.5 Ethane 1.0 Methane 0.5 Ether Nitrous oxide structures of the anesthetic molecules, it is understandable that there would be some differences in the clinical profiles of each anesthetic drug. The interactions of inhaled anesthetic molecules with the chreodes are weak and nonspecific. The patterns of the side chains forming the chreode create local asymmetries that may produce different responses to chiral isomers of an anesthetic agent. A recent study has modeled segments of chreodes using cellular automata dynamics.36 When the diffusion behavior of chiral molecules was compared, it was found that there were modest differences in the rate of diffusion out of these segments, between stereoisomers. This corresponds to the modest stereospecificity observed with some anesthetics.7,8 Circular dichroism studies have revealed that chiral molecules produce chiral solvent structure in their vicinity.39 Since chreodes may be associated with many receptors and enzymes, such an interference in their function and influence is expected to be widespread. Their influence may be inhibitory, as at receptor-chreode systems, or reinforcing as at reuptake sites supported by a chreode network. In summary, the presence of an inhalation anesthetic agent in a chreode system supporting a ligand diffusion to a receptor may alter the structure and 0.89 0.43 hence the function of the chreode thereby reducing the diffusion and the receptor response. The summation of these numerous diffusion disruption events leads to the manifestation of clinical anesthesia. REFERENCES 1. Eckenhoff RG. Promiscuous ligands and attractive cavities. Molec Interven. 2001;1:258-268. 2. Campagna JD, Miller KW, Forman SA. Mechanisms of actions of inhaled anesthetics. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2110-2124. 3. Meyer H. Theory of alcohol narcosis. Arch Exp Pathol Pharmacol. 1899;42:109-110. 4. Overton E. Studien uber die Narkose. Jena, Germany: Fisher. 1901. 5. Richards CD, Keightley CA, Hesketh TR, Metcalfe JC. A critical evaluation of the lipid hypothesis of anesthetic action. In: Fink BR, ed. Molecular Mechanisms of Anesthesia. New York, NY: Raven Press; 1980. 6. Franks NP, Lieb WR. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of general anesthesia. Nature.1994;367:607-614. 7. Franks NP, Lieb WR. Steriospecific effects of inhalation general anesthetic optical isomers on nerve ion channels. Science. 1991; 254:427-430. 8. Lysco GS, Robinson JL, Castro R, Ferrone RA. The stereospecific effects of isoflurane isomers in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263: 25-29. 9. Baber J, Ellena JF, Cafiso DS. Distribution of general anesthetics in phospholipid bilayers determined using 2H NMR and 1H – 1H NOE spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6533-6539. 10. Xu Y, Tang P. Amphiphilic sites for general anesthetic action? Evidence from 129Xe-[1H] intermolecular nuclear Overhauser effects. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1323:154-162. AANA Journal/December 2003/Vol. 71, No. 6 427 11. Franks NP, Lieb WR. Do general anesthetics act by competitive binding to specific receptors? Nature. 1984;310:599-601. 12. Franks NP, Lieb WR. Temperature dependence of the potency of volatile general anesthetics: Implications for in vitro experiments. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:716-720. 13. Harrison NL, Kugler JL, Jones MV, Greenblatt EP, Pritchett DB. Positive modulation of human gamma-aminobutyric acid type A and glycine receptors by inhalation anesthetic isoflurane. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44:628-632. 14. Eckenhoff RG, Johansson JS. Molecular interactions between inhaled anesthetics and proteins. Pharmacol Rev. 1997;49:343-367. 15. Nicoll RA, Madison DV. General anesthetics hyperpolarize neurons in the vertebrate central nervous system. Science. 1982;217:1055-1056. 16. Nakahiro M, Yeh JZ, Brunner E, Narahashi T. General anesthetics modulate GABA receptor channel complex in rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. FASEB J. 1989;3:1850-1854. 17. Greiner AS, Larach DR. The effect of benzodiazapine receptor antagonism by flumazenil on the MAC of halothane in the rat. Anesthesiology. 1989;70:644-648. 18. Rich GF, Sullivan MP, Adams JM. Effect of chloride transport blockade on the MAC of halothane in the rat. Anesth Analg. 1992; 75:103-106. 19. Wong SM, Cheng G, Homanics GE, Kendig JJ. Enflurane actions on spinal cords from mice that lack the beta3 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:154-164. 20. Orliaguet G, Vivien B, Lageron O, Bouhemad B, Coriat P, Riou B. Minimum alveolar concentration of volatile anesthetics in rats during postnatal maturation. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:734-739. 21. Eckenhof RG. An inhalational anesthetic binding domain in the nicotinic cetylcholine receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93: 2807-2810. 22. Greenblatt EP, Meng X. Divergence of volatile anesthetic effects in inhibitory neurotransmitter receptors. Anesthesiology. 2001;94: 1026-1033. 23. Raines DE, Claycomb RJ, Scheller M, Forman SA. Nonhalogenated alkane anesthetics fail to potentiate agonist actions on two ligand-gated ion channels. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:470-477. 24. de Sousa SL, Dickinson R, Lieb WR, Franks NP. Contrasting synaptic actions of the inhalational general anesthetics isoflurane and xenon. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1055-1066. 25. Eckenhoff RG, Johansson JS. On the relevance of “clinically relevant anesthetic concentrations” in in vitro studies. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:856-860. 428 AANA Journal/December 2003/Vol. 71, No. 6 26. Okazaki N, Takai K, Sato T. Immobilizationm of a sensitive plant, mimosa pudica L., by volatile anesthetics. Masui-Japanese J Anesthesiol. 1993;42:1190-1193. 27. Morton A, Mathews BW. Specificity of ligand binding in a buried nonpolar cavity of T4 lysozyme: Linkage of dynamics and structural plasticity. Biochemistry. 1995;34:8576-8588. 28. Brunori M, Vallone B, Cutruzzola F, et al. The role of cavities in protein dynamics: crystal structure of a photolytic intermediate of a mutant myoglobin. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2058-2063. 29. Kier LB, Cheng CK, Testa B. A cellular automata model of ligand passage over a protein hydrodynamic landscape. J Theor Biol. 2002;215:415-426. 30. Welch GR. The enzymatic basis of information processing in the living cell. Biosystems. 1996:38:147-153. 31. Hasinoff BB. Kinetics of acetylthiocholine binding to electric eel acetylcholinesterase in glycerol/water solvents of increased viscosity. Evidence for a diffusion-controlled reaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;704:52-58. 32. Chou K-C, Zhou G-P. Role of the protein outside an active site on the diffusion-controlled reaction of an enzyme. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:1409-1413. 33. Welch GR. On the free energy “cost of transition” in intermediary metabolic processes and the evolution of cellular infrastructures. J Theor Biol. 1977;68:267-279. 34. Birch GG, Latymer Z. Intensity/time relationships in sweetness: Evidence for a queue hypothesis in taste chemoreception. Chem Senses. 1980;5:63-78. 35. Waddington CH. The Strategy of the Gene. London, England: George Allen & Unwin Ltd Publishers; 1957:29-38. 36. Kier LB, Cheng CK, Testa B. Studies of ligand diffusion pathways over a protein surface. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2003;43:42-45. 37. Scatena LF, Brown MG, Richmond GL. Water at hydrophobic surfaces: Weak hydrogen bonding and strong orientation effects. Science. 2001;292:908-909. 38. Zhang X, ZhuY, Graick S. Hydrophobicity at a janus interface. Science. 2002;295:663-665. 39. Fidler J, Rodger PM, Rodger A. Chiral solvent structure around chiral molecules: Experimental and theoretical study. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:7266-7273. AUTHOR Lemont B. Kier, PhD, is professor of Medicinal Chemistry and Nurse Anesthesia and a senior fellow in the Center for the Study of Biological Complexity, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Va.