Youth Culture

advertisement

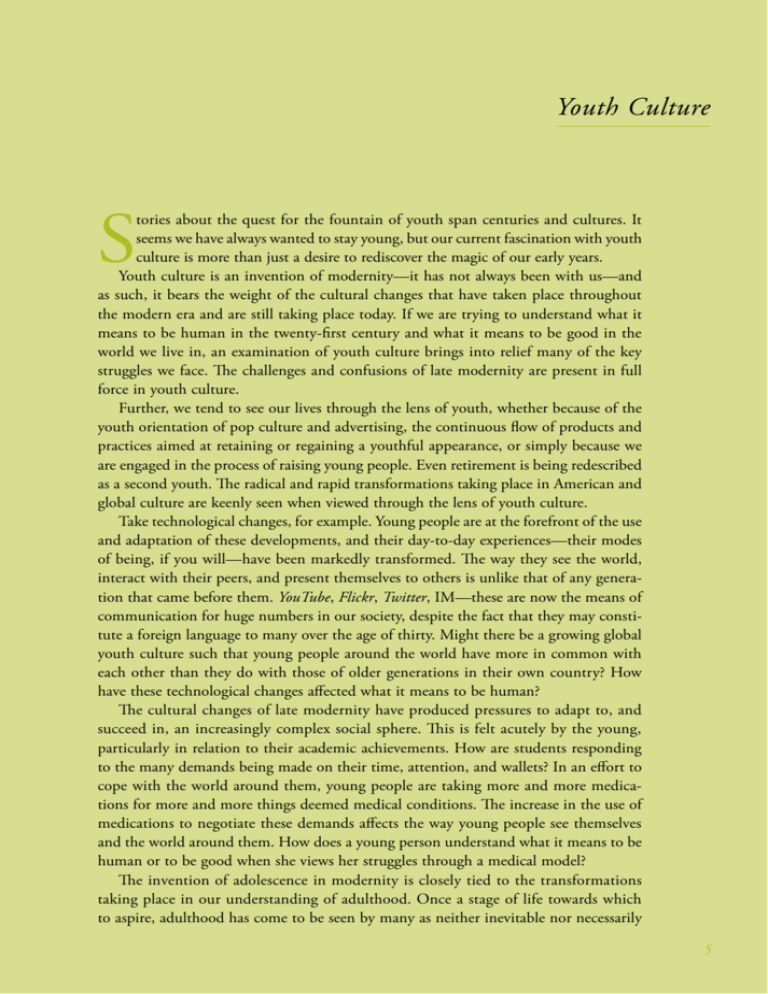

T itle / N ame Youth Culture S tories about the quest for the fountain of youth span centuries and cultures. It seems we have always wanted to stay young, but our current fascination with youth culture is more than just a desire to rediscover the magic of our early years. Youth culture is an invention of modernity—it has not always been with us—and as such, it bears the weight of the cultural changes that have taken place throughout the modern era and are still taking place today. If we are trying to understand what it means to be human in the twenty-first century and what it means to be good in the world we live in, an examination of youth culture brings into relief many of the key struggles we face. The challenges and confusions of late modernity are present in full force in youth culture. Further, we tend to see our lives through the lens of youth, whether because of the youth orientation of pop culture and advertising, the continuous flow of products and practices aimed at retaining or regaining a youthful appearance, or simply because we are engaged in the process of raising young people. Even retirement is being redescribed as a second youth. The radical and rapid transformations taking place in American and global culture are keenly seen when viewed through the lens of youth culture. Take technological changes, for example. Young people are at the forefront of the use and adaptation of these developments, and their day-to-day experiences—their modes of being, if you will—have been markedly transformed. The way they see the world, interact with their peers, and present themselves to others is unlike that of any generation that came before them. YouTube, Flickr, Twitter, IM—these are now the means of communication for huge numbers in our society, despite the fact that they may constitute a foreign language to many over the age of thirty. Might there be a growing global youth culture such that young people around the world have more in common with each other than they do with those of older generations in their own country? How have these technological changes affected what it means to be human? The cultural changes of late modernity have produced pressures to adapt to, and succeed in, an increasingly complex social sphere. This is felt acutely by the young, particularly in relation to their academic achievements. How are students responding to the many demands being made on their time, attention, and wallets? In an effort to cope with the world around them, young people are taking more and more medications for more and more things deemed medical conditions. The increase in the use of medications to negotiate these demands affects the way young people see themselves and the world around them. How does a young person understand what it means to be human or to be good when she views her struggles through a medical model? The invention of adolescence in modernity is closely tied to the transformations taking place in our understanding of adulthood. Once a stage of life towards which to aspire, adulthood has come to be seen by many as neither inevitable nor necessarily 5 desirable. The meaning of adulthood in contemporary life is in a state of confusion. What happens to a culture when people don’t want to grow up? What does this say about our ideals for what it means to be human and for what it means to be good? The phenomenon of wanting to avoid adulthood is especially interesting given that youth—teenagers, in particular—are depicted in such a negative light in today’s media. Adolescence and crime are portrayed as highly correlated. News stories about teenagers frequently highlight violence, gangs, and the like, continuing a long tradition of portraying teenagers as trouble. What cultural anxieties does this skewed portrayal of youth reveal? And what does the history of the word “adolescence” tell us about the ways we understand this time in our lives and those who are currently in it? These are some of the questions that this issue of The Hedgehog Review explores. We can learn a great deal about the transformations currently shaping contemporary culture by looking at the experiences of youth today, as well as our own perceptions of youth. Young people are often the first to adopt new cultural forms, and we often express our anxieties about those new cultural forms as concerns about the young. Thus, the study of youth culture is also a study of the broader culture such that the most pressing concerns, the most exciting changes, and the potential for good and for damage are writ large and boldly. The stakes are at their highest—what is more precious to us or more vulnerable than the young in our midst—but the possibilities are also at their greatest: young people carry the world forward, and they are the ones ultimately who will reap the benefits or the deficits of how we negotiate the cultural changes of contemporary life. —T.H.R. 6