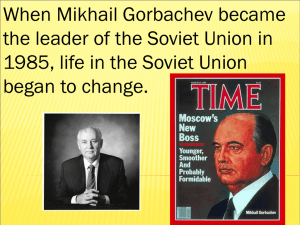

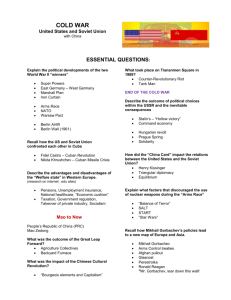

Perestroika: Reformation of the Soviet Economy

advertisement