Fitzpatrick on Stalin – Domestic

advertisement

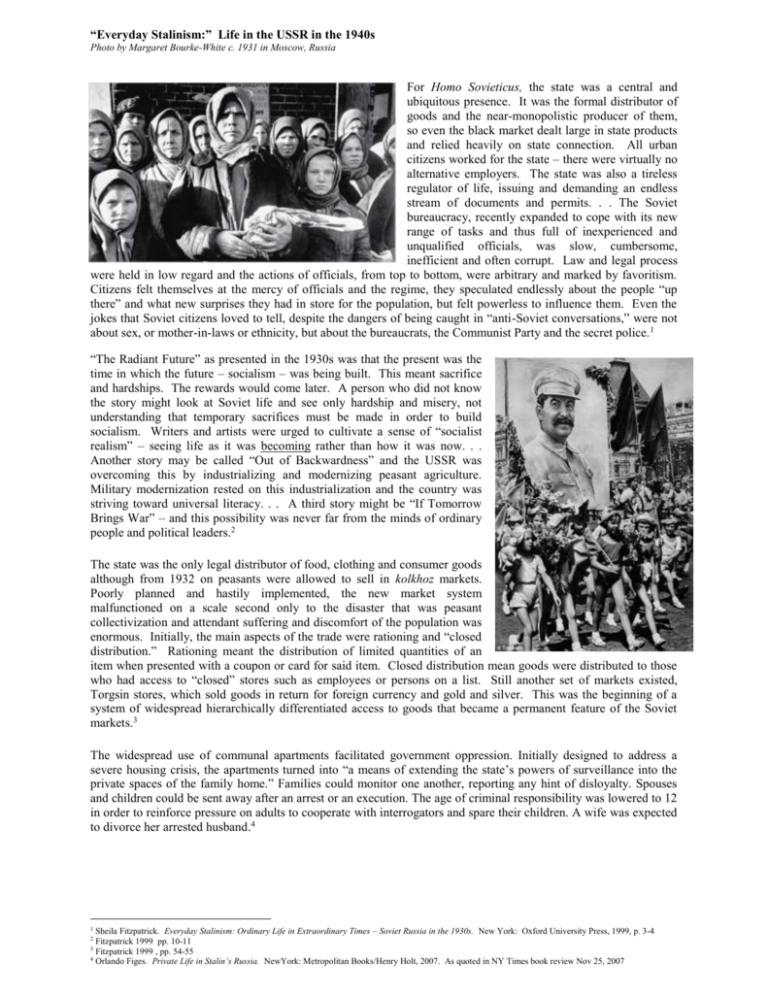

“Everyday Stalinism:” Life in the USSR in the 1940s Photo by Margaret Bourke-White c. 1931 in Moscow, Russia For Homo Sovieticus, the state was a central and ubiquitous presence. It was the formal distributor of goods and the near-monopolistic producer of them, so even the black market dealt large in state products and relied heavily on state connection. All urban citizens worked for the state – there were virtually no alternative employers. The state was also a tireless regulator of life, issuing and demanding an endless stream of documents and permits. . . The Soviet bureaucracy, recently expanded to cope with its new range of tasks and thus full of inexperienced and unqualified officials, was slow, cumbersome, inefficient and often corrupt. Law and legal process were held in low regard and the actions of officials, from top to bottom, were arbitrary and marked by favoritism. Citizens felt themselves at the mercy of officials and the regime, they speculated endlessly about the people “up there” and what new surprises they had in store for the population, but felt powerless to influence them. Even the jokes that Soviet citizens loved to tell, despite the dangers of being caught in “anti-Soviet conversations,” were not about sex, or mother-in-laws or ethnicity, but about the bureaucrats, the Communist Party and the secret police. 1 “The Radiant Future” as presented in the 1930s was that the present was the time in which the future – socialism – was being built. This meant sacrifice and hardships. The rewards would come later. A person who did not know the story might look at Soviet life and see only hardship and misery, not understanding that temporary sacrifices must be made in order to build socialism. Writers and artists were urged to cultivate a sense of “socialist realism” – seeing life as it was becoming rather than how it was now. . . Another story may be called “Out of Backwardness” and the USSR was overcoming this by industrializing and modernizing peasant agriculture. Military modernization rested on this industrialization and the country was striving toward universal literacy. . . A third story might be “If Tomorrow Brings War” – and this possibility was never far from the minds of ordinary people and political leaders.2 The state was the only legal distributor of food, clothing and consumer goods although from 1932 on peasants were allowed to sell in kolkhoz markets. Poorly planned and hastily implemented, the new market system malfunctioned on a scale second only to the disaster that was peasant collectivization and attendant suffering and discomfort of the population was enormous. Initially, the main aspects of the trade were rationing and “closed distribution.” Rationing meant the distribution of limited quantities of an item when presented with a coupon or card for said item. Closed distribution mean goods were distributed to those who had access to “closed” stores such as employees or persons on a list. Still another set of markets existed, Torgsin stores, which sold goods in return for foreign currency and gold and silver. This was the beginning of a system of widespread hierarchically differentiated access to goods that became a permanent feature of the Soviet markets.3 The widespread use of communal apartments facilitated government oppression. Initially designed to address a severe housing crisis, the apartments turned into “a means of extending the state’s powers of surveillance into the private spaces of the family home.” Families could monitor one another, reporting any hint of disloyalty. Spouses and children could be sent away after an arrest or an execution. The age of criminal responsibility was lowered to 12 in order to reinforce pressure on adults to cooperate with interrogators and spare their children. A wife was expected to divorce her arrested husband.4 Sheila Fitzpatrick. Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times – Soviet Russia in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 3-4 Fitzpatrick 1999 pp. 10-11 Fitzpatrick 1999 , pp. 54-55 4 Orlando Figes. Private Life in Stalin’s Russia. NewYork: Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt, 2007. As quoted in NY Times book review Nov 25, 2007 1 2 3