A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

advertisement

Gilles Labrie

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

Gilles Labrie

Central Michigan University

ABSTRACT

This article discusses a project to design and implement a small French

vocabulary tutor for the World Wide Web. The tutor includes words, pictures, and sounds to help students learn new words and their pronunciation. The article highlights salient features and design of the tutor and

then focuses on two variants of a module on technology-related vocabulary that were created using very straightforward html code and JavaScript.

It also demonstrates the increased complexity and control made possible

with Java applets. Finally, it explores strategies for including various features, for example, hot spots that can be used on the Web. Preliminary

assessment reveals that Web-based multimedia programs have some advantages over more traditional methods of vocabulary learning.

KEYWORDS

Computer-Assisted Language Learning, World Wide Web, French Vocabulary Tutor, JavaScript, Java Applets

INTRODUCTION

Vocabulary acquisition is important in language learning as both foreign language students and teachers will attest. It is important to beginning speakers of a language who substantially increase their power to communicate by increasing the number of words they know. It is also important to intermediate and advanced speakers who often feel they have difficulty communicating effectively because of their inadequate vocabulary.

Vocabulary can be learned by trying to understand spoken or written

language. Researchers like Krashen argue that comprehensible input is

the only effective means of vocabulary and language learning. Others (Nation, 1990; Oxford & Crookall, 1990) maintain that less contextualized

language can also be useful in vocabulary learning and that both direct

and indirect strategies ought to be used.

© 2000 CALICO Journal

Volume 17 Number 3

475

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

Some of the strategies for vocabulary learning reviewed by Oxford and

Crookall include: (a) decontextualized techniques (e.g., word lists, flashcards, and dictionary use), (b) semicontextualized techniques (e.g., word

grouping, word or concept association, visual imagery, aural imagery, keywords, physical response, physical sensation, and semantic mapping), and

(c) fully contextualized techniques (practice in reading, listening, speaking, and writing).

THE GOALS OF THE PROJECT

This project is being developed as an attempt to use semicontextualized

techniques to provide an effective and enjoyable means of learning French

vocabulary. The project has two major goals. The first is to design and

implement a few modules of a small French vocabulary tutor for the World

Wide Web. The Tutor includes words, pictures, and sounds. The second

goal is to assess the effectiveness of the Tutor. Using one of the modules,

a preliminary study asked the following questions:

1. Do students spend more time learning vocabulary with a computer-based tutor than they do with a textbook?

2. Do they learn more with computer-based tutors than with traditional means of vocabulary study?

3. Do they find vocabulary learning more helpful and enjoyable

with computers than with the tools they regularly use?

THE TUTOR

The Tutor has two modes: a learning mode and a game mode. The learning mode, which allows students to learn words and their pronunciation,

is modeled on visual dictionaries that have pictures and words linked to

the pictures. The Tutor, as does the CD-ROM version of the dictionary Le

Visuel multilingue (1996), associates sounds with pictures and text.

The words in the Tutor are divided into associated word groups. Modules for two word groups were first developed: one teaching the parts of

the body and the other a collection of technology-related words. Since

then, a module on fruit and vegetables has been developed and others are

currently being designed. The dictionaries for the individual modules differ; the vocabulary items for the parts of the body module all refer to a

single picture, whereas the technology vocabulary is presented sequentially as a collection of pictures, each picture representing one word. If

students pass the cursor over the picture or an area of the picture, the

corresponding word appears alongside and a translation in English ap476

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

pears in the status window below. If students click on the picture (or area

of the picture) the word is pronounced in French.

The game mode includes two basic games: one in which students drag

words to the picture or area of the picture they represent and another one

in which the program pronounces the word and students must click on

the relevant picture or area of the picture. The program provides a score

for the number of correct answers and indicates the elapsed time since the

start of the game.

Students use the Tutor in the learning mode to study, review, and learn

words. Using the dictionary, they can practice and get immediate feedback on the meaning of words and how they are pronounced. In the game

mode, students can use either game, the one focusing on the written word

and the other on the spoken word to test their knowledge of the vocabulary. Because students get points for correctly identifying spoken or written words, their score provides them with a target that they can try to

better. Moreover, because the timer in the program indicates elapsed time,

students can try to improve both their accuracy and response speed.

SALIENT FEATURES

First, the learning mode consists of a text dictionary divided into word

groups. Each group provides a network of associated words, pictures and

sounds that enhances learning. As Carter and McCarthy (1988) have noted,

“the more words are analyzed or enriched by imagistic and other associations, the more likely it is that they will be retained.”

Second, the Tutor allows for systematic vocabulary learning. Often, after the first two years of study, vocabulary is not stressed. More advanced

students can use the program to learn groups of words which are not

familiar to them but which they might want to know.

Third, because the program is web based, it is widely available (accessible at http://www.chsbs.cmich.edu/fllc/glabrie/dict/tindex.html). The

Tutor replaces the note cards students often make to help them learn words

and has more elements: not just words, but also pictures and sounds.

Fourth, the game mode provides a sense of learning by doing. Increasingly greater associations are created among text, sounds, and pictures as

students try to connect written and spoken words with a picture or an

area of a picture.

Finally, learners have complete control. It is clear that learners best learn

the words they want to learn. The Tutor is a hypertext document with

many links between the various exercises and gives learners maximum

mobility from one part of the program to another. Learners do not need to

proceed in a linear fashion through exercises.

In short, the Tutor is distinctive because it incorporates picture, words,

Volume 17 Number 3

477

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

and sounds, includes games (play is an important element in sustained

learning), and, especially, is Web based, making it widely available.

JAVASCRIPT VERSION

The module on technology vocabulary exists in three versions; one in

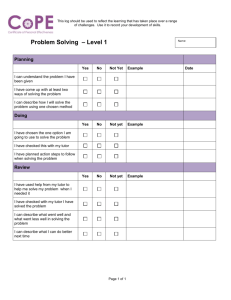

JavaScript, one in html code only, and a third, more flexible version created as a Java applet. In the JavaScript version, shown in Figure 1, two

pictures appear centered on the screen aligned next to two white spaces of

similar size on either side.

Figure 1

Technology Vocabulary: JavaScript version

When students pass the cursor over the picture, the corresponding word

appears in French in the white space next to the picture. If students click

on the picture or the white space, the word is spoken in French. This

module requires three different pictures: a picture of the item (e.g., a computer), a picture of the word typed on a white background (computer3.gif),

478

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

and a blank white background (blank1.gif). Below is the html code for the

first two of the 27 pictures in the group:

<HTML><HEAD>

<SCRIPT LANGUAGE=“JavaScript”>

function doit(word, num, trans) {

document.images[num].src= word + “3.gif”;

window.status=“a ” + trans;

}

function undo(word, num, trans) {

document.images[num].src= word + “1.gif”;

window.status=“ ”;

}

</SCRIPT></HEAD><BODY>

<A HREF=“comput.wav” //This is # 0

onMouseOver=“doit(‘comput’, 0,’computer’);return true”

onMouseOut=“undo(‘blank’, 0,’ ‘)”>

<IMG SRC=“blank1.gif” BORDER=“0” WIDTH=“100” HEIGHT=“100”></A>

<A HREF=“comput.wav” //This is # 1

onMouseOver=“doit(‘comput’,0,’computer’);return true”

onMouseOut=“undo(‘blank’, 0,’ ‘)”>

<IMG SRC=“comput.gif” BORDER=“0” WIDTH=“147” HEIGHT=“100”></A>

<A HREF=“monitr.wav” //This is # 2

onMouseOver=“doit(‘monitr’, 3, ‘monitor’);return true”

onMouseOut=“undo(‘blank’, 3, ‘ ‘)”>

<IMG SRC=“monitr.gif” BORDER=“0” WIDTH=“114” HEIGHT=“100”></A>

<A HREF=“monitr.wav” //This is # 3

onMouseOver=“doit(‘monitr’, 3, ‘monitor’);return true”

onMouseOut=“undo(‘blank’, 3, ‘ ‘)”>

<IMG SRC=“blank1.gif” BORDER=“0” WIDTH=“100” HEIGHT=“100”></A>

….

</BODY></HTML>

When the cursor is moved over the picture, OnMouseOver calls the function “doit,” which paints the word in French on a white background

(computer3.gif). The function also puts the translation in the status window. When the cursor leaves the area, the function OnMouseOut calls the

blank picture with the white background, and the word disappears. Because the audio file is anchored to the picture, if students click on the

picture, the audio file “computer.wav” is played, and the words for a computer are spoken in French.

Pictures and Sounds

Because pictures on the Web will be widely disseminated, permission is

required to use the pictures of others; a better solution is to use one’s own

pictures. Pictures can be taken using a digital camera, or color prints can

be digitized using a scanner. Scanning pictures is relatively simple since it

is easy to learn how to use Adobe Photoshop or other image software to

Volume 17 Number 3

479

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

crop images or reduce the size of files. Most institutions have staff in

computer labs who are eager to help faculty developers. Once pictures

have been cropped, they should be used on the Web in their actual size;

otherwise the pictures may be distorted. Pictures should be digitized in

.jpeg or .gif format, if they are to be used in Java applets. The files should

also be small enough in size so that browsers can load them in a reasonable amount of time.

The Sound Recorder program on the PC can be used to record sound

files. Recording is straightforward and is easily learned using the help

files, but the quality is often mediocre and does not approach that which

can be obtained with professional quality equipment. The sound files in

the initial module of the Tutor are in .wav format. In the applets discussed

below, the sound files are in the .au format required by Java. Shareware

programs such as Goldwave are also available on the Web for easy conversion to and from most audio formats.

HTML VERSION

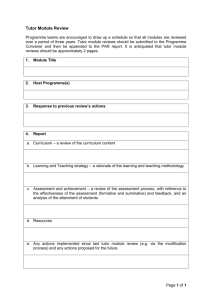

An HTML variant of the module on technology vocabulary is in fact

possible with the use of the <ALT> tag (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Technology Vocabulary: HTML Version

480

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

This tag was originally designed to provide an alternative text for browsers unable to view images in a Web document. However, many current

browsers also display the alternative text when the mouse pointer is over

an image. Thus, the code below, showing the first four of the 27 images,

provides a variant of the JavaScript version above. The anchor first encloses the audio file. Within the anchor, the audio file is followed by the

image file and the <ALT> tag that encloses the information to appear on

the screen when the cursor moves over that image.

<HTML><BODY><CENTER>

<A HREF=“comput.wav”> <IMG SRC=“comput.gif” ALT=“un ordinateur” BORDER=“0” WIDTH=“147” HEIGHT=“100”></A>

<A HREF=“monitr.wav”><IMG SRC=“monitr.gif” ALT=“un écran” BORDER=“0”

WIDTH=“114” HEIGHT=“100”></A>

<A HREF=“mouse.wav”><IMG SRC=“mouse.gif” ALT=“une souris” BORDER=“0”

WIDTH=“57” HEIGHT=“100”></A>

<A HREF=“keybd.wav”> <IMG SRC=“keybd.gif” ALT=“un clavier” BORDER=“0”

WIDTH=“231” HEIGHT=“100”></A>

</CENTER>

….

</BODY></HTML>

This version is the easiest to construct and can be easily implemented by

means of a Web page editor such as Netscape Page Composer. With the

editor, developers first import the images onto the new page and then link

each image to its sound file so that clicking on the image causes the corresponding word to be pronounced. To have the word appear on the screen

when the cursor moves over the image, developers must add the word in

the alternative text box in the lower portion of the dialog box that appears

when importing the image file. The page created with the editor is quite

similar to the actual page as it appears on the Web; what you see in the

Web page editor is what you get when the page appears on the Web. The

creator of the page need not deal directly with the html tags, although the

html document with tags is being created in the background by the Web

page editor.

JAVA VERSION

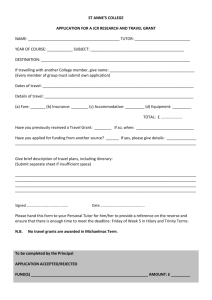

The Java version of the module is composed of a Java applet embedded

in the html code read by the Web browser (see Figure 3).

Volume 17 Number 3

481

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

Figure 3

Technology Vocabulary: Java Version

In this version, the pictures scroll across the screen, three at a time. When

the cursor passes over one of the pictures, the corresponding word appears in French below; if students click on the picture, the corresponding

word is spoken in French. When the html code appears in the browser, the

embedded applet is automatically called. The html code with the call to

the applet follows.

<HTML><HEAD><TITLE> technology vocabulary </TITLE></HEAD>

<BODY BGCOLOR=“#0000F F” TEXT=“#FF0 000” LINK=“#FF0 000”

LINK=“#FF0000”><CENTER><TABLE><TR><TD></TD><TD ALIGN=CENTER>

<APPLET CODE=“picture.class” ALIGN=“center” WIDTH=575 HEIGHT=150 >

<PARAM NAME=“number_of_images” VALUE=“28”>

<PARAM NAME=“showing” VALUE=“3”>

<PARAM NAME=“image1” VALUE=“comput”>

<PARAM NAME=“translation1” VALUE=“a computer”>

<PARAM NAME=“french1” VALUE=“un ordinateur”>

...

</APPLET></TD><TD></TD></TR></TABLE></CENTER></BODY></HTML>

482

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

Code, the first tag within the applet, lists the name of the file the browser

will run. The first parameter indicates the number of pictures, and the

second the number showing on the screen at any one time. The next three

parameters provide a name for the first picture, a translation of the word,

and the French word for the pictured item. This information is repeated

for all the words on the list. Other words and pictures are substituted for

the ones used here to create other modules such as the one on fruit and

vegetables, all using this same applet.

The items passed to the applet vary in number depending on what the

applet needs. Here is some of the code that calls the applet on parts of the

body.

<APPLET CODE=“body.class” ALIGN=“center” WIDTH=398 HEIGHT=424 >

<PARAM NAME=“number_of_images” VALUE=“1”>

<PARAM NAME=“image1” VALUE=“parts_of_body”>

<PARAM NAME=“number_of_words” VALUE=“25”>

<PARAM NAME=“audio1” VALUE=“cheveux”>

<PARAM NAME=“audio2” VALUE=“tete”>

<PARAM NAME=“audio3” VALUE=“sourcils”>

….

</APPLET>

The “number_of_images” parameter specifies the number of pictures the

applet calls, in this case only one. The next parameter specifies the name

of the image, “parts_of_body,” the parameter “number_of_words” specifies how many the applet uses, and the next three parameters specify the

names of the audio files.

A JAVA APPLET

Traditional linear computer programs follow a prescribed sequence. For

example, the program for an ATM waits for a card to be inserted in the

machine. Once a card has been inserted, the program asks for a password.

After entering the password, the user is given a number of choices, but the

choices are fixed. In short, the program starts in a fixed place with the

insertion of a card and proceeds in a linear fashion through a series of

choices that end when the card is returned to the user. Everything is fairly

predictable, except the amount of cash the user wants and other minor

variations.

However, Windows programs in general, and Java applets in particular,

do not behave in this manner; they do not follow a predictable linear script.

In the beginning, as with the ATM, the applet is running and waiting for

something to occur. However, the applet does not follow a prescribed sequence of events but, instead, responds to what the user does with the

cursor. This approach requires a different kind of program. First, an applet

Volume 17 Number 3

483

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

has an “init” method which, as the name indicates, performs initial tasks

such as loading pictures and sound files into memory. It also has a paint

method which literally paints onto the screen the picture loaded in the

“init” method. The paint method is regularly called to repaint the screen.

Finally, handlers exist for the so-called events, that is, the movement of

the cursor as it enters and exits the applet area as well as the movement of

the cursor within the applet area. These handlers also determine what

happens when the mouse button is pressed. Whenever any of these events

occurs, the program captures the event and the coordinates of the cursor

at the time of the event.

Loading the Images

Loading the images is one of the first tasks performed by the applet.

This task is accomplished in the “init” method with the code below:

numimgs = Integer.parseInt( getParameter(“numimgs”));

resize(width, height);

imgnames = new String[numimgs];

img = new Image[numimgs];

for (int k=0; k < numimgs; k++) {

imgnames[k] = getParameter(“img” + (k+1));

img[k]=getImage(getDocumentBase(),imgnames[k]+”.jpg”);

}

First, the value in the html code of the parameter “number_of_images” is

read. Then two new array variables are declared; “imgnames” will be used

to store the names of the pictures, and “img” to store the pictures themselves. The loop that follows fills the first array with the names of the

images from the html parameter list, then loads the images in the array

“img.”

Loading the Sound Files

The sound files are then loaded with similar code.

audionum = Integer.parseInt( getParameter(“audionum”));

audionames = new String[audionum];

audio = new AudioClip[audionum];

for (int k = 0; k < audionum; k++) {

audionames[k] = getParameter(“aud” + (k+1));

audio[k]=getAudioClip(getDocumentBase(),audionames[k]+ .au”);

}

484

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

The number of audio files is determined by reading the parameter list in

the html code. Arrays are declared for the names of the audio files and for

the files themselves, and a loop is used to read the file names from the

parameter list in the html code; the audio files are then read into the array.

Once the files are loaded, the paint method literally paints the images on

the screen.

Creating the Hot Spots

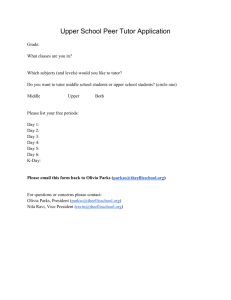

In the module on parts of the body, shown in Figure 4, a picture of a

young man is painted on the screen. (See the Java code for this applet in

Appendix A.)

Figure 4

Vocabulary for Parts of the Body

Volume 17 Number 3

485

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

When students move the cursor over a part of the image, the word for the

part of the body appears in French on the screen. Causing the word to

appear on the screen is done with so-called “hot spots.” Hot spots can

easily be defined in Java using the point, rectangle, and polygon classes.

Because rectangles are fixed in shape, the polygon class was used to delimit the irregular shapes of parts of the body. Any number of coordinates

can be included to create a “hot spot” on the picture of the body. First, the

x and y coordinates for the polygon are defined in pixels.

Int[]

Int[]

xcheveux = {158,166,184,221,236,241 };

ycheveux = { 0,21,8,13,27,0};

These points are easily found because, as the applet is being developed, a

preliminary version runs with the picture and a function prints the x and y

coordinates of the cursor movements in the status window. Once the points

are defined, the new polygon can be specified.

Polygon cheveux = new Polygon(xcheveux,ycheveux, 6);

The parameter list includes “xcheveux” and “ycheveux” (i.e., the array of

points previously defined followed by the number of points in the polygon). The MouseMoved handler automatically tracks the movement of

the cursor on the screen and the coordinates are saved in the variable

“point.” The paint method then writes the appropriate French word to the

screen if “point” is inside the area defined as the polygon “cheveux.” It

does so by calling the DrawString method to print the word at the specified location on the screen.

if (cheveux.contains(point.x,point.y)){

g.drawString(“les cheveux”, 10, 18);

}

Playing the Audio Files

Whenever the mouse is clicked in an area of the picture representing a

part of the body listed in the vocabulary, the word is spoken. This procedure is performed by the MousePressed handler.

public void mousePressed (MouseEvent evt) {

if (point == null) { point = new Point (evt.getX( ), evt.getY( ));}

point.x = evt.getX( ); point.y=evt.getY( );

if (cheveux.contains(point.x,point.y)){

audio[0].play( );

}

else if (tete.contains(point.x,point.y)){

audio[1].play( );

}

486

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

The MousePressed handler is constantly tracking the position of the cursor. If the mouse is clicked, the MousePressed block is entered, and the x

and y coordinates of the cursor on the screen are assigned to point.x and

point.y. If the coordinates, point.x and point.y, are inside the polygon previously defined as “cheveux,” the corresponding audio file is played.

GAME MODE

The game mode of the Tutor was described earlier. One of the games

directs students to click on a button to hear a word and then on the picture that corresponds to that word (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Game

A second button, when pressed, repeats the last word spoken. The layout

therefore requires the addition of two buttons, play and repeat, as well as

text boxes to indicate the score and the time elapsed. Instructions to students also need to be displayed, which are best added by creating a new

Volume 17 Number 3

487

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

layout, imbedding the previous layout within the new layout, and adding

the new features in turn at the bottom.

In the game, a run method is added to determine the elapsed time. This

part of the code follows.

Public void run ( ) {

While (initial Time == 0);

While (mythread != null) {

Try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

If (!stop)

{

Time = System.currentTimeMillis();

Interval = Time – initialTime;

minutes = (int) Interval/60000;

secondes = (int) (Interval % 60000)/1000;

tf3.setText(String.valueOf(minutes));

tf4.setText(String.valueOf(seconds));

}

} catch (Exception e) { }

}

}

The initial time is set to zero; then an infinite loop constantly updates the

number of minutes and seconds elapsed, and the SetText method prints

the results in the appropriate text box. Finally, a method is needed to respond when a button is pressed. The buttons are defined as follows:

Button

String

b[ ] = new Button[number];

button_name[] = {“Entendre”, “Répéter”}

Button clicks are processed by the actionPerformed handler. If the play

button is selected, the handler randomly selects a word not already used

and causes the word to be spoken. If the repeat button is pressed, the

previous word is played again.

Public void actionPerformed (ActionEvent e) {

If ( e.getSource( ) == “Entendre” && !stop) {

If (initialTime == 0) initialTime = System.currentTimeMillis();

Voicenum = (int) (java.lang.Math.random () * 4);

Do { if yes[voicenum]);

Else {

voicenum++;

If (voicenum > 4) voicenum = 0;

}

} while (!yes[voicenum}));

audio[voicenum].play(); essais++; tf2.setText(String.valueOf(essais));

} else if (e.getSource( ) == “Répéter” && !stop) {

audio[voicenum].play(); essais++; tf2.setText(String.valueOf(essais));

}

}

488

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT

A preliminary assessment of the tutor was completed with students from

Elementary Spanish classes who were paid a minimal fee for participating

in the study. Spanish students were used in the study because they represented a large relatively homogeneous group with experience learning foreign language vocabulary. Consequently, it was felt that the vocabulary

learning they were asked to do in the study was a task they were more

likely to know how to undertake and complete than students who had

never studied a foreign language. The students were paid a fee because

local experts advised that the recruitment of volunteers could be greatly

facilitated if a modest stipend were offered. Of the 66 students who participated, the scores of 50 were retained. In a questionnaire administered

at the end of the project, the participants were asked which languages

they had studied and, to eliminate bias in the results, the scores of the 16

students who had previously studied French were eliminated (See the student questionnaire in Appendix B).

Protocol

The students were asked to study 23 French vocabulary words, all related to parts of the body. (See the list of words in Appendix C.) All students studied the same words, but they were divided into three groups

that were directed to study the vocabulary items in different ways. The

students in group 1 (n = 17) studied the words on a computer. When they

passed the cursor over an area of the image on the screen, the word appeared in French next to it. If they clicked the left mouse button on the

same area, the word was spoken in French. The students in group 2 (n =

17) also studied the words on a computer, but they were unable to hear

the words spoken; they could only see the word appear in French on the

screen when they moved the cursor over an area of the body. The students

in group 3 (n = 16) worked with a more traditional printed version of

what the other students had studied on the computer. In fact, they worked

with three modified copies of the picture in Figure 4 above. Printed on the

first copy were all the words related to the head. The second copy contained the words that are part of the arms and upper body. The third copy

included the words related to the legs and feet. The words printed on

these pages, however, had to be connected with lines to specific areas of

the body. To make the pictures less confusing, dots were added so that it

would be clear which areas of the body the printed words represented. To

assure that all the participants worked under the same conditions, the

picture with the dots was also used in the computer versions for the two

other groups of students.

Volume 17 Number 3

489

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

No limit on the amount of time students were permitted to study was

imposed. They simply recorded the time they started studying the words

and the time they finished. After the students indicated they had studied

to their satisfaction, they completed three tests covering all the vocabulary items. In the first test, they were given English words and asked to

write the French equivalents (English to French); in the second, they were

given French words and asked to write the English equivalents (French to

English); in the third, they listened to a list of words spoken in French and

were asked to write the English equivalents (listening/French to English).

The tests were each scored on the basis of 23 points. For tests where the

students answered in English, correct or mostly correct responses were

awarded one point. On the test where responses were in French, one point

was awarded for correct or mostly correct answers and one-half point for

answers where the word was recognizable.

Study Time

Students in Group 1, those who used the computer and who could hear

the words pronounced, spent an average of 14.5 minutes studying the

vocabulary items. Students in Group 2, those who used the computer but

who could not hear the words pronounced, studied an average of 13.0

minutes. Students in Group 3, those who used the traditional method,

studied for 17.6 minutes on average. Analysis of variance showed that

there was a significant difference between the Groups 2 and 3, those who

used the computer without sound versus those who used traditional methods (p < .05).

Correlation Between Test Scores

The students completed three tests after they had finished studying the

vocabulary. The analysis of students’ test scores showed a significantly

high correlation between the English to French and the French to English

test scores (p < .01) and a moderate correlation between the English to

French scores and the listening scores and also between the French to

English scores and the listening scores (p < .01). In other words, students

who did well on one test also did well on the others, and students’ scores

on one test were good predictors of their scores on the other tests.

Comparison of Test Scores Between Groups

The mean scores and standard deviations on the three tests for each

group of students are shown in Table 1.

490

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

Table 1

Mean Test Scores

Group 1

Group 2

Group 3

English to

French

M (SD)

15.5 (5.49)

19.4 (3.31)

16.7 (5.19)

French to

English

M

(SD)

20.3 (3.82)

22.0 (2.09)

19.9 (3.69)

Listening/French

to English

M

(SD)

15.2 (5.75)

14.9 (3.92)

11.8 (5.04)

There were no significant differences among the groups on the three test

scores, which suggests that the three methods are equally effective. The

test scores are also pertinent because the students in Group 3, using traditional methods, studied longer but scored no better on the tests. These

results suggest that working with a computer is a more efficient way of

studying than using traditional methods.

As noted earlier, all the students had studied Spanish. When we adjusted for the years of study of Spanish (using years of study of Spanish as

the covariate in analysis of covariance), significant differences emerged

among the groups on the listening test. The students in Groups 1 and 2

had significantly higher scores than those in Group 3. Post hoc analysis

also showed a significant difference between Groups 1 and 3 and between

Groups 2 and 3 on the listening test. In other words, when the test scores

were adjusted for years of Spanish, students who studied the vocabulary

with a computer scored significantly higher on the listening test than students using traditional methods. The difference on the listening test scores

between the two groups using computers was not significant, but the test

only assessed the students’ ability to recognize new words, not to pronounce them.

Helpfulness and Enjoyableness

A part of the assessment was based on student self-evaluation. We wanted

to find out whether students thought that computer-based lessons were

effective and found them enjoyable. In the questionnaire that the students

completed at the end of the session, we asked the following two questions:

1) How helpful was this method in learning vocabulary?

2) How enjoyable was this method of learning vocabulary?

Students’ responses to these questions are shown in Table 2 and Table 3,

and the means for the responses to the first question are shown in Table 4.

Volume 17 Number 3

491

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

Table 2

Helpfulness of Each Method of Learning

very helpful

somewhat

or helpful

helpful

Group 1

15

Group 2

13

3

Group 3

9

6

Table 3

Enjoyableness of Each Method of Learning

very enjoyable

somewhat

or enjoyable

enjoyable

Group 1

10

6

Group 2

9

8

Group 3

7

4

not very or

not helpful

1

1

not very or

not enjoyable

1

5

Table 4

Mean Response Scores on Helpfulness of the Method

M

Group 1

3.23

Group 2

2.76

Group 3

2.62

Note: 5-point scale (0 = not helpful, 4 = very helpful)

Analysis revealed a moderate correlation between helpfulness and enjoyment. Students who found the way they learned the French words helpful

also found it enjoyable to a similar degree. There were no significant differences among the ratings of the groups for the question of how enjoyable they found the specific method they used to learn the words. However, on the question of how helpful the method was, Group 1, the group

of students who used computers and could hear the words pronounced,

had a significantly higher mean than the other two groups. This finding

indicates that the students found computer-based learning with sound more

helpful than those who used the computer without sound and those who

used traditional methods. However, one large caveat should be noted.

Because students were given a listening test, one would expect those who

heard the words to find the materials more helpful than those who did

not.

The questionnaire also asked students what was helpful and what was

not, and what suggestions they would like to offer. The answers to these

questions supported the conclusion in the self-evaluation on helpfulness.

Students in Group 1 reacted very positively to the program. 29% com492

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

mented favorably saying, for example, that “this method of learning is a

good one,” that they “would like to be taught like that,” that this method

of learning should “be used in all language classes,” and that the “program

should be available in all language labs.” Another student praised the effectiveness of the program:” I never thought I could speak French, but

here I knew how to say body part terms in a matter of minutes.”

A few students in Group 2, who used the computer without having the

words pronounced, pointed out that they liked using the computer program because a word only appeared when the cursor was moved over an

area of the body. Therefore, they could test their knowledge and verify it

immediately by moving the cursor and making the word they wanted to

check appear on the screen.

Suggestions for Improvements

Students also suggested a number of improvements. Some pointed out

the poor placement and ambiguity of some of the dots painted on parts of

the body. Even when the dots are well placed, however, the question of

how learners distinguish among the words for thigh, leg, or calf remains.

For that reason, a number of students, including 29% of those in Group 1

who responded favorably to the program, suggested that the English equivalents of all words be shown somewhere. In addition, of the students who

did not hear the words pronounced, 52% of those in Group 2 and 29% of

those in Group 3 would have liked to hear the words. The latter request,

however, is not surprising given that students had just taken a listening

test.

CONCLUSION

A few conclusions can be gleaned from the preliminary assessment of

the program in this study.

• Students using paper copies spent more time on average studying vocabulary than both groups of students using a computer,

though the only significant difference was between Groups 2

and 3. It is noteworthy that the students using traditional methods studied longer but scored no better on the achievement

tests.

• Students who did well on one test tended to do well on the

others and vice versa. Students’ scores on one test were good

predictors for scores on the other two tests.

• In general, the three methods of vocabulary learning were

Volume 17 Number 3

493

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

equally effective. Only when we adjusted for the years of study

of Spanish was there a significant difference in listening test

results between the two groups using a computer versus the

noncomputer group.

• Students did not find one learning method more enjoyable than

another.

• The analysis showed that Group 1 students using pictures,

words, and sounds found the method they used more helpful

than students in the two other groups who used pictures and

words, with or without a computer. This result does not necessarily mean that students find computer-based learning more

helpful than other means of study. Students in Group 1 seemed

to find their method of learning inherently more useful because

they practiced listening to the words and were better prepared

for the listening test that followed. The only support for this

hypothesis is the strong testimony from some of the students in

Group 1.

As for the Tutor, the design described above is merely the first step;

many more words need to be added to the lexicon. Indeed, this development should proceed more quickly now that a few basic applets have been

created. In addition, other types of exercises and games could be included

in the future. One of the games already developed in which students drag

the vocabulary word to the area of the picture it represents has been extended so that it can be played by two students on the Web. The present

speed of the Internet, however, is too slow, without turn taking, to permit

the game to proceed in the usual fashion. The program will need to be

modified.

494

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

Appendix A

Java Code Applet

/*

*

*/

import java.awt.*;

import java.applet.*;

import java.lang.Object;

import java.awt.event.*;

/* This applet shows 1 image on the screen. If the user moves the mouse over parts of

* the image, the word corresponding to that part of the image appears in French. If the

* user clicks on the image, the word is pronounced in French.

*/

public class body extends Applet implements MouseListener, MouseMotionListener {

int

width

= 600;

int

height

= 424;

Image[ ]

img;

int

numimgs;

String[ ]

imgnames;

AudioClip[ ]

audio;

int

audionum;

String[ ]

audionames;

String[ ]

translate;

String[ ]

word;

String

mes1

= “ “;

Font

font = new Font(“TimesRoman”, Font.BOLD,24);

Font

font2 = new Font(“TimesRoman”, Font.BOLD,14);

int[ ]

xcheveux = {158,166,184,221,236,241 };

int[ ]

xtete = {200,200,207,207 };

int[ ]

ycheveux = { 0,21,8,13,27,0};

int[ ]

ytete = {9,18,18,9};

Polygon

cheveux = new Polygon ( xcheveux, ycheveux, 6);

Polygon

tete = new Polygon ( xtete, ytete, 4);

….

Graphics

dbuffer;

Image

offscreen;

public void init ( ) {

setBackground(Color.white);

setFont(font);

numimgs = Integer.parseInt( getParameter(“numimgs”));

resize(width, height);

imgnames = new String[numimgs];

img = new Image[numimgs];

for (int k=0; k < numimgs; k++) {

imgnames[k] = getParameter(“img” + (k+1));

img[k]=getImage(getDocumentBase(),imgnames[k]+”.jpg”);

}

Volume 17 Number 3

495

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

audionum = Integer.parseInt( getParameter(“audionum”));

audionames = new String[audionum];

audio = new AudioClip[audionum];

for (int k = 0; k < audionum; k++) {

audionames[k] = getParameter(“aud” + (k+1));

audio[k]=getAudioClip(getDocumentBase(),audionames[k]+ .au”);

}

ofscreen = createImage(width,height);

dbuffer = offscreen.getGraphics();

dbuffer.setColor(Color.white);

dbuffer.fillRect(0,0,width,height);

addMouseListener(this);

addMouseMotionListener(this);

}

public void paint (Graphics g) {

g.setColor(Color.blue);

g.setFont(font2);

for (int k=0, j =0; k < numimgs ; k++) {

dbuffer.drawImage(img[k], j, ystart, img[k].getWidth(this), img[k].getHeight(this),

this);

}

g.drawImage(offscreen, 0, 0, this);

if (cheveux.contains(point.x,point.y)){

g.drawString(“les cheveux”, 10, 18);

}

else if (tete.contains(point.x,point.y)){

g.drawString(“la tête”, 10, 18);

}

….

}

public void update (Graphics g) {

paint(g);

}

public void mousePressed(MouseEvent evt) {

if (point == null) { point = new Point (evt.getX(),evt.getY());}

point.x = evt.getX(); point.y=evt.getY();

if (cheveux.contains(point.x,point.y)){

audio[0].play( );

}

else if (tete.contains(point.x,point.y)){

audio[1].play( );

}

…

}

public void mouseEntered (MouseEvent evt) {

repaint( );

}

public void mouseExited (MouseEvent evt) {

repaint( );

}

496

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

public void mouseClicked (MouseEvent evt) {

}

public void mouseReleased (MouseEvent evt) {

}

public void mouseMoved(MouseEvent evt) {

if (point == null) { point = new Point (evt.getX(),evt.getY());}

point.x = evt.getX(); point.y=evt.getY();

repaint();

showStatus(point.x +”,” + point.y);

}

public void mouseDragged(MouseEvent evt) {

}

}

Appendix B

Student Questionnaire

I.

Please circle one of the choices for each question.

1. How helpful was this method of learning vocabulary?

very

somewhat

not very

not

helpful

helpful

helpful

helpful

helpful

2. How enjoyable was this method of learning vocabulary?

very

somewhat

not very

not

helpful

helpful

helpful

helpful

helpful

II. What was helpful?

What was not helpful?

What suggestions do you have?

What languages have you studied and how long?

Volume 17 Number 3

497

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

Appendix C

Vocabulary List

les cheveux

les sourcils

l’oeil

le nez

la bouche

le menton

l’oreille

le cou

l’épaule

le bras

l’estomac

les doigts

la main

le coude

la poitrine

le dos

le poignet

le genou

la cuisse

la jambe

le pied

le doigt de pied

la cheville

498

hair

the eyebrows

the eye

the nose

the mouth

the chin

the ear

the neck

the shoulder

the arm

the stomach

the fingers

the hand

the elbow

the chest

the back

the wrist

the knee

the thigh

the leg

the foot

the toe

the ankle

CALICO Journal

Gilles Labrie

REFERENCES

Carter, R., & McCarthy, M. (1988). Vocabulary and language learning. New York:

Longman.

Corbeil, J.-C. (1994). Le Visuel multilingue: dictionnaire thématique. Montréal:

Editions Québec/Amérique.

Farrell, J. (1999). Java Programming. Cambridge, MA: ITP.

Geary, D. (1998). Graphic Java 2: Mastering the JFC: AWT. Mountain View, CA:

Sun Microsystems.

Le Visuel: dictionnaire multimédia [CD-ROM]. (1996). Montréal: Editions Québec/

Amérique.

Nation, I. (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. New York: Newbury House.

Oxford, R., & Crookall, D. (1990). Vocabulary learning: A critical analysis of techniques. TESOL Canada Journal, 7 (2), 9-30.

Reynolds, M. C. (1996). Using JavaScript. Indianapolis, IN: Que.

Stanek, W. R. (1996). Web publishing unleashed. Indianapolis, IN: Sams.net.

Tyma, P., Torok, G., & Downing, T. (1996). Java primer plus. Corte Modera, CA:

Waite Group Press.

Van der Linden, P. (1999). Just Java 1.2. Mountain View, CA: Sun Microsystems.

AUTHOR’S BIOSTATEMENT

Gilles Labrie is Professor of French at Central Michigan University. He is

interested in the use of technology to enhance language learning.

AUTHOR’S ADDRESS

Gilles Labrie

Department of Foreign Languages, Literatures, and Cultures

Central Michigan University

Mt. Pleasant, MI 48859

Phone: 517/774-3786

Fax:

517/774-2323

E-mail: gilles.labrie@cmich.edu

Volume 17 Number 3

499

A French Vocabulary Tutor for the Web

AGORA

LANGUAGE

www.agoralang.com

for comprehensive listings of language publishers,

schools, study abroad, learning center services,

500

CALICO Journal