Lineups & Pretrial Identification: Rights & Procedures

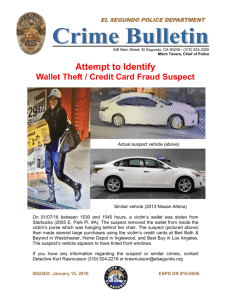

advertisement