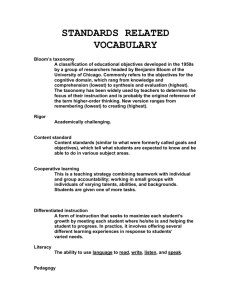

Philosophical Perspectives

advertisement