Adoption and Permanent Care Learning Guide

advertisement

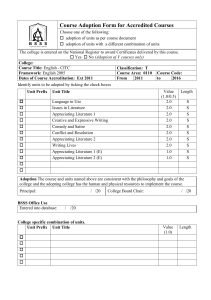

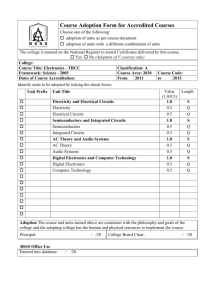

Contents 1.1 Introduction: Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 1.1.1 3 The structure of the learning guide 3 How to use the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 3 1.1.2 Reflective practice 4 1.1.3 Supervision 4 What is supervision? 5 Supervision in Adoption and Permanent Care 5 – The administrative or management function 5 – The educative function 5 – The supportive or enabling function 6 – The mediation function 6 Expectations of supervision 6 Confidentiality in supervision 8 1.1.4 Confidentiality, privacy and release of information 8 Privacy legislation 8 Confidentiality 9 Privacy and collection and release of information. 9 – Release of information 9 – Collection of information under the Adoption Act and the Children and Young Persons Act 10 Storage of information 10 Transfer of personal information between agencies 10 Correction of information 10 1.2 Adoption and permanent care in context 12 1.2.1 Adoption 12 1.2.2 Permanent care 12 1.2.3 History of child protection in Victoria 13 1.2.4 Adoption and permanent care teams 13 1.2.5 Function and structure of the Department of Human Services 14 Head office of the Department of Human Services 15 Regional offices of the Department of Human Services 15 1.3 Life issues of adoption and permanent care 16 1.3.1 Loss 17 1.3.2 Search for identity 17 1.3.3 Entitlement 18 Adoptive or permanent care parents 18 Birth parent 18 Persons raised in care: the child 18 2 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 1.3.4 Issues for the adopted person 19 1.3.5 Issues for adoptive or permanent care parents 20 1.3.6 Issues for the birth parent 21 1.4.7 Mourning the loss 22 Denial 23 Anger 23 Bargaining 23 Depression 23 Acceptance 23 1.4 Checklist of things to do 25 In the first six weeks 25 As soon as can be arranged 25 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 1.1 3 Introduction: Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide Learning goals • To introduce the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide. • To introduce reflective practice. • To reinforce the importance of supervision. • To reinforce issues surrounding privacy, confidentiality and release of information. Adoption and permanent care in Victoria is provided to regional offices of the Department of Human Services through ten services; four located in the Department of Human Services and six located in community service organisations (CSO). The teams work closely together to place children, and interagency and interregional placements are common. Workers in adoption and permanent care (A&PC) have long recognised the need for a comprehensive induction program that will assist in ensuring commonality of practice between A&PC teams and increase the confidence of workers in relation to their own work as well as increasing their understanding of the work of other teams. This learning guide provides that program. 1.1.1 The structure of the learning guide A&PC is a small but complex program area with fewer than fifty workers spread through ten agencies. Workers come to A&PC with varying experience. The Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide is a self-learning program designed to provide information on the breadth of issues relevant to placing children in adoption and permanent care. It introduces a structured model of thinking—Reflective Practice—to enhance practice. There are exercises and readings to be completed and discussed with your supervisor in each section. The guide may be used individually or in small groups and provides common resources for all teams. The Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide contains four divisions which are sub-divided into sections related to specific tasks of workers or specific knowledge areas for adoption and permanent care. Each section is an independent unit: • Part 1 (Introduction) contains an overview of adoption and permanent care and introduces workers to life issues of adoption and permanent care. The introduction covers supervision, reflective practice, release of information and privacy and confidentiality issues. • Part 2 (Adoption) covers the Adoption Program • Part 3 (Permanent care) covers the Permanent Care Program. • Part 4 (Special issues of adoption and permanent care) provides information on issues relevant to adoption and permanent care such as child development, infertility and disability. Each team has a supplement to the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide which contains reference material for use by all workers. How to use the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide This learning guide covers a range of issues in adoption and permanent care. You should, however, use every opportunity to explore issues with your supervisor who has had experience in the field and will guide your learning. The learning guide is not designed to be used within a short induction period as a worker starts with the agency. Rather, it is expected that it will be used throughout your first year of work in A&PC as areas of work are introduced. There is considerable flexibility regarding how the guide can be used. Each section contains a discussion of issues and a series of activities which explore the issues. Exercises are generally designed to be followed by discussion with your supervisor or in small-group discussion with workers at the same introductory phase of work or within team meetings. Although some of the exercises may seem detailed, you will gain more by doing them than from simply reading the text. You may choose to work through the guide sequentially or to select sections relevant to your assigned work. For example, if you are given a permanent care placement to supervise, you would turn to Section 3.11: Permanent care placement supervision and Section 3.12: Permanent care placement support to introduce yourself to the issues involved in placement supervision and support in permanent care. Later, when an adoption assessment is assigned, you would work 4 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide through Section 2.2: Adoption assessment. Each section is designed to be completed independently. Where other sections of the learning guide or additional reading would enhance your understanding, they are identified within the section. Case material is presented to illustrate issues in adoption and permanent care. One case is followed for adoption; a second case is presented for permanent care. The complete case studies are contained in the Supplement to the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide. Alternatively, you and your supervisor may decide to use current cases to complete the exercises. 1.1.2 Reflective practice Protective Services has introduced ‘reflective practice’, a structured model of adult learning which encourages review and evaluation of practice, in the Protective Services beginning practice learning guide. Reflective practice does not rely on a single framework to define work but rather defines a systematic way of thinking about addressing issues in practice. It is a useful tool for practice in adoption and permanent care and will be referred to throughout this learning guide. Resource Child Protection beginning practice learning guide, Section 1: Introduction—Reflective practice. Kolb is an educationalist who has written extensively about adult learning. Reflective practice is a concept within Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. To summarise, Kolb states that adults learn from their experiences and that this process of learning involves four key elements: • experience • reflection • conceptualisation • active experimentation. Reflective practice involves reflecting on and analysing information and actions with the goal of understanding of issues and growth in practice. It involves systematic inquiry into practice and encourages theoretical and practical learning. It aims to build upon knowledge and skills and to put concepts and theories into practice. It is a cycle of continuous learning. Reflective practice can be readily translated into your casework tasks in adoption and permanent care as described below. • Experience—List what you know about the situation. Be careful that you stick to facts or direct statements from the clients that can be verified and do not slip into interpretation or hypothesising. You will review, add to and adjust as you work with the people. • Reflection—List what you think the meaning is of the information or behaviours. You have considerable personal and professional experience to define your thinking. • Conceptualisation—Attempt to develop a way of understanding the information or behaviour. At this stage you may develop some hypotheses to check, compare consistent patterns of behaviour and develop constructs to explore with your supervisor regarding the meaning of the information. • Active experimentation—Active experimentation is the exploration of your reflection and conceptualisation to define your assessment and develop and implement intervention plans. As you proceed with your work with the client, you will refine your thinking, eliminate constructs that do not fit and, by the end of the process, develop an understanding of the situation and plan intervention strategies. Review is built into the process. Adjustment of practice results from the analysis and review. 1.1.3 Supervision Supervision is an essential element of working with people and of practice in adoption and permanent care. Your supervisor is your greatest support and should be informed of all your work. All practitioners will meet new situations which provide the opportunity for continued learning. You have a responsibility to yourself, your clients and your agency to use supervision to best advantage. Your agency has the obligation to provide supervision and to ensure accountability of the service. Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 5 What is supervision? Supervision is a learning model through which a worker develops competent, accountable practice, pursues continuing professional development, gains personal support and relates to the employing agency through working with a person who has experience in the field. Resources Child Protection beginning practice learning guide, Section 2.6: Supervision The Child Protection beginning practice learning guide defines the following purposes of supervision: • developing and acknowledging good practice • ensuring positive practice occurs • promoting mutual learning • maintaining and improving quality of practice • assisting professional development • ensuring roles and responsibilities are clear • supporting workers in the work • adhering to guidelines and practice standards • resourcing practitioners • ensuring accountability to children and families • assisting the supervisee to prevent, reduce and handle stress. Taking the time to read Section 2.6 of the Beginning practice learning guide will assist you to understand the process and the role of supervision in practice. Supervision in adoption and permanent care Most agencies have guidelines and policies regarding supervision of workers and consider supervision to be more than accountability. The supervision you receive will reflect the policy of your agency. It is expected that adoption and permanent care workers will receive formal supervision at least fortnightly. Formal supervision includes discussion and review of cases and other tasks related to work. It has an educative focus with the setting and review of learning goals. It includes assignment of work and discussion of agency issues. Supervision should provide support to the worker to perform tasks effectively. Most agencies now have a system of performance review in place which may be a part of the supervision process. Informal supervision includes responses to questions which arise between sessions and should be available when needed. Team supervision is a means of providing educative supervision on topics of interest to all team members and can be used to facilitate discussion of matters of concern to all in the agency. It should be available regularly for all workers. Four functions of supervision: The administrative or management function This function is concerned with work performance and ensuring accountability to clients and to relevant bodies. The function ensures understanding of roles, policy and procedures and compliance with the expectations of the agency. The educative function This function is about learning and development as a worker. Training and developmental needs are identified and professional and learning goals to develop practice are set. Skills are developed and theory is integrated with practice. 6 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide The supportive or enabling function This function is about you and provides the opportunity to explore the interaction between your work, your values, beliefs and other factors that influence your work. It provides time to debrief and should provide an accepting atmosphere to explore your feelings, concerns and successes. The mediation function In all our work there is a tension between the ideal and the reality. Organisations are not perfect and resources are often scarce. Advocacy is often needed for services for families and interagency work does not always run smoothly. Your supervisor may need to mediate or assist you to mediate where issues arise. Expectations of supervision Supervision is a dynamic process which requires input from you and your supervisor. It is a planned process with goals to achieve. It should include the four functions described above and should include periodic review of both the process and worker progress. You have a responsibility to make supervision successful. Each worker needs to define their expectations of supervision, set learning goals and be prepared to discuss learning needs, cases and work issues with their supervisor. Each worker must be prepared to participate in supervision and to address issues that may arise in the supervision process in an open way. Activity Think of an experience of positive supervision, then think of an experience of poor supervision. What did you learn from each experience? What do you expect from supervision? Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide What do you expect from your supervisor? How do you think you supervisor can best facilitate your learning needs? Set two learning goals to discuss with your supervisor. In your next supervision session, discuss your expectations and learning goals with your supervisor. 7 8 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide Confidentiality in supervision Trust and respect are important elements to enable workers to share with their supervisor. Trust and respect require confidentiality • that is mandated for the client • that is necessary to your relationship with your supervisor. There are some issues that should remain within supervision. They include information regarding clients and discussion of personal work-related issues. Both your supervisor and you should maintain confidentiality. 1.1.4 Confidentiality, privacy and release of information In the course of your work, you will collect personal information about children, their birth and adoptive or permanent care families. This information is highly confidential. All persons with whom you are in contact need to be aware that the information must be treated with respect. You should familiarise yourself with your agency policy on confidentiality and privacy. Privacy legislation Confidentiality of information and privacy are governed by practice ethics, agency policy and by several Acts. There are a number of principles adhered to across the Acts governing adoption and permanent care, but it is necessary to refer directly to the relevant Acts when making decisions regarding collection and release of information. Resources Sharing information in out-of-home care; 2003/10 Child Protection and care practice Instruction available in the supplement to the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide. Your agency policy on privacy. Your agency policy on confidentiality. The relevant Acts for adoption and permanent care are: The Adoption Act 1984 The Children and Young Persons Act 1989 The Freedom of Information Act 1982 The Victorian Privacy Act 2000 The Commonwealth Privacy Act 1988 The Health Records Act 2001 The governing principles of the privacy legislation are: • All decisions relating to the disclosure of personal information must be taken considering the best interest of the person. • Only relevant information should be recorded. • People should be advised of the purpose of collecting information, and the purposes to which it may be put. • The person’s interests in controlling what information is recorded about them should be respected. • Collection of information should not intrude unreasonably on the personal affairs of the person to whom it relates. • Personal information should be stored securely. • Release of information should be determined on a need-to-know basis, rather that a want-to-know basis. • The consent of the person should be sought each and every time the release of information is proposed. (Note: there are exceptions to this consent requirement.) • A record of the type of information kept about individuals and how to access this personal information should be maintained. • People have a right to correct and update information recorded about them. Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 9 The Department of Human Services Sharing information in out-of-home care practice guidelines is consistent with the governing principles of the privacy legislation. These guidelines and your agency’s policy and procedures regarding privacy should be followed when making decisions regarding release of information. Confidentiality Discussion with clients and information received about clients are confidential. This information is not to be disclosed without a clear purpose or, wherever possible, without consent of the person. All agencies have policies regarding confidentiality and every worker should familiarise themselves with the policy. In practice confidentiality means that clients should be interviewed in private where they cannot be overheard. Workers should not discuss cases in public places where they can be overheard by persons not related to the case. Workers should not talk of cases outside the office and should not disclose information to other professionals unless there is a need to know, such as reporting to a supervisor or in case-related discussion with other professionals. Privacy and collection and release of information Privacy legislation reinforces confidentiality of information and provides guidelines for the collection, correction, storage and release of information. You must become familiar with your agency’s requirements. Release of information The situation regarding release of information in adoption and permanent care is complex. Adoption and permanent care teams collect information about applicants and children and their birth parents, which may need to be released to other parties. You must become familiar with the legislation and if you are unsure regarding release of information, check with your supervisor and agency privacy officer. Children and Young Persons Act 1989 The Children and Young Persons Act 1989 restricts the release of information regarding a child and birth family. In the context of child protection, the primary reason for collecting information about a child and family is to ensure the safety and wellbeing of children. When children are subsequently placed in permanent care, there is a clear expectation that they receive care which provides for their wellbeing and safety. We are not therefore prevented by privacy legislation from disclosing such information so long as it is disclosed for the primary purpose for which it was collected; that is, to provide for the child’s safely and wellbeing. The child protection and care practice instruction ‘Sharing information in out of home care’ available in supplement to the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide highlights the principle that information collected for the care of a child can be disclosed to those people who provide care for the child. Adoption Act 1984 The Adoption Act 1984 restricts the release of identifying information to parties to an adoption. When the child is under 18 years old, only non-identifying information can be disclosed without the consent of all parties. Part VI of the Adoption Act— Adoption Information Provisions—allows for adult adopted persons and adult children of adopted persons to receive identifying information regarding the birth family without the consent of the relevant parties. In all other circumstances a party to an adoption, including the birth parents, may receive non-identifying information only unless the relevant other party has given written permission to provide identifying information. In effect this means that neither the birth or adoptive parents nor an adopted person under 18 can receive identifying information about another party to the adoption without consent. The Act provides for the adopted person to apply to the Adoption and Family Records Service of the Department of Human Services or an adoption information service of a CSO to receive identifying information at age 18. At that time, the adopted person may receive a copy of the adoption record including the court record and original birth certificate. The provisions of the Adoption Act 1984 are different to those of the Children and Young Persons Act 1989. When a child is placed in permanent care a decision must be made as to whether the location of the placement is revealed to the birth parent. If this information is to remain confidential, a case will have to be made to the court that the birth parent should not be informed. The child may obtain his or her records at the age of 18 by applying under the Freedom of Information Act to the Department of Human Services. 10 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide Collection of information under the Adoption Act and the Children and Young Persons Act In adoption and permanent care, detailed information is obtained from applicants as part of the assessment process. It is important to remember that the collection of information about any person or couple must relate to the purposes for which it is obtained. Section 35 of the Adoption Regulations 1998 and Section 8 of the Children and Young Persons Custody and Guardianship Regulations 2001 define the areas which must be considered during the assessment of persons seeking approval to adopt a child or provide permanent care. For both assessments you are required to consider the applicants’ personality, age, medical, physical and mental health, maturity, financial circumstances, and stability of relationship to determine if they can care for a child. The areas covered in the assessment report relate to each of the areas specified in the Regulations. Applicants should be made aware of the requirements of the Regulations and of the relevance of each area of data collection to the care of the child. Storage of information The Privacy Act 2000 sets out responsibilities for ensuring that information collected and stored about clients is kept confidential and is only available to those people who are designated to share the information. Information must be stored in a secure setting. Your agency has policies and procedures which meet the requirements of the Act. The Adoption Act 1984 requires that adoption records be stored in perpetuity. The permanent care program maintains records utilising the same principle. The records may not be destroyed. You will need to become familiar with the record system of your agency, how information is recorded and stored, and how to access stored hard copy and electronic records. Transfer of personal information between agencies There are ten adoption and permanent care teams in Victoria. Because of the need to place cross-regionally to ensure provision of the best home for the child, personal information is shared between agencies directly and through the Central Resource Exchange (CRE) operated through the head office of the Department of Human Services. Wherever possible, consent is obtained from the relevant party prior to transfer of information between agencies. Where it is impractical to obtain the consent and the information is essential for the wellbeing and optimal care of the child, the reason for transferring the data should be noted in the record. Because of the complexity of the provisions of the various Acts, it is recommended that wherever possible consent be obtained for release of any information from the relevant party prior to the information being released. As you become familiar with the procedure manuals you will note procedures for obtaining consent to release information are a part of the assessment process in both adoption and permanent care. When using mail, transfer of personal information is generally by registered mail. When original documents such as consent for adoption are sent to the solicitor for legalisation, they must be forwarded by registered mail or by courier. The guidelines for electronic transfer of data are less clear. Each agency should ensure that every precaution is taken to ensure that the information will not be read by outside agents. Generally, reports transferred by email are sent as attachments with a security statement as part of the original message. The FAX cover sheet generally contains a privacy message and a request that the document be returned or destroyed if delivered incorrectly. Correction of information Users of the service are entitled to request that information in their records be corrected. The general practice is to append the correction to the relevant part of the record in order that the requested change is readily apparent. The record itself is not altered. In assessment of parents there is the possibility of disagreement with decisions of the Applicant Assessment Committee (AAC) and the review of that decision. The applicant is entitled to disagree with the decision and to present their view. The worker’s assessment will remain unchanged and the applicant’s written comments will be attached to the file. The AAC makes a decision regarding the suitability of applicants on the basis of all information available. Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 11 Activity Arrange to meet with the administration staff of your agency to be briefed on your agency’s record system. How is information recorded? How is information stored? How are records accessed? Ask about: – hard copy – electronic information – use of FAX – use of email – security measures – confidentiality policy. Obtain a copy of your agency’s privacy and confidentiality policy. Discuss with your supervisor. 12 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 1.2 Adoption and permanent care in context Learning goal • To provide a context for adoption and permanent care within the child welfare system. Adoption and permanent care came into being to meet the needs of children within the broader child welfare system. The development of these services is intricately tied with protection and care of children and reflects changing social attitudes through the 20th century. Permanent care and adoption provide permanent placements for children who are unable to be cared for within their birth families and who otherwise would not be raised in a secure family environment. 1.2.1 Adoption The first adoption Act was proclaimed in 1928. Adoption was seen to provide a solution to the stigma of illegitimacy for both the child and the birth mother who relinquished the child. It provided an alternative to institutional care of children at a time when large numbers of children were in care. It also provided a solution for parents who were unable to have children of their own. The underlying assumption of adoption was that children would become part of the adoptive family, just as if they were born into the family, and no legal or social distinction would be made between the adoptive and biological children of a family. There have been three adoption Acts in Victoria: 1928, 1968 and 1984. The Acts reflect the history of increasing regulation in the care of children and evolution of social attitudes. Although secrecy was not incorporated into the Adoption Act 1928, it was encouraged in practice. The 1968 Act prohibited giving information whereas the 1984 Act opened adoptions to information exchange and contact between birth relatives, the adopted person and the adoptive family. 1.2.2 Permanent care Permanent Care Orders were introduced through the Children and Young Persons Act 1989. The concept grew out of the reform movements of the 1970s and 1980s which opened adoption to contact between the birth parent, child and adoptive parents and challenged decision making processes and ‘welfare drift’ within the child welfare system. The concept of permanent care rather than adoption was developed to address issues of connection with the child’s family of origin, to maintain family relationships, and to provide permanent families for children who were unable to be cared for within their birth family. Permanent care is firmly placed in child welfare services. Permanent care provides families for children when the State has intervened on behalf of the child and has determined that the child cannot live safely with the birth parents on a long-term basis. As it has developed, permanent care serves children who have experienced significant abuse and neglect and disrupted placements. Both adoption and permanent care rely on volunteer families to provide care for children. Initially it was believed that the permanent care family would become independent of welfare services, offering children a ‘normal’ experience of growing up in a family, thus eliminating dependence on welfare services. The assumption that the families would become independent of services, however, has proved to be limited. Families who care for children who have experienced significant harm in the care of their birth parents are generally in need of long-term assistance. Adoption and permanent care are best understood within the context of child protection services. Resources Child Protection professional development learning guide beginning practice Section 1.2: Child protection—an introduction Child protection—a historical perspective Section 1.4: The organisational context Protecting children—a partnership approach The Department of Human Services—functions and structures Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 13 1.2.3 History of child protection in Victoria The Child Protection beginning practice learning guide contains a brief history of child protection in Victoria and identifies current trends. This learning guide is available in your agency and workers are encouraged to read the identified sections to gain a better understanding of the context within which we work. In summary, colonial Australia did not have local welfare traditions nor were services provided by the church or private organisations. Early emphasis in child welfare was on provision of care for destitute children with the State taking on responsibility for their care. Pressure for care and protection of children increased. The Children’s Court of Victoria and the Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Children (later the Children’s Protection Society) were established in 1896. The focus at this time was on neglect and abandonment of children. The Children’s Protection Society has maintained an active role in child welfare to the present but, in the 1980s, relinquished its role in investigation of reports of child abuse. Initially, the focus of child protection was care of destitute children. Churches established children’s homes to rescue children in moral danger and children suffering from abuse and neglect. Children’s homes and maternity hospitals were active in placement of children within families where the children were fostered, adopted or boarded out. The Department played a major role in the support of children and in supervision of placements. By the 1920s there were a significant number of children in care in children’s homes who would not return to their family. There was pressure to find alternatives for these children which ultimately led to the Adoption Act 1928. In the 1960s and 1970s ‘the battered baby syndrome’ was recognised as a socio-medical issue and was added to the focus on neglect and abandonment. The 1970s also saw a move away from institutional placement to foster care as the preferred style of care for children. Concurrently there was a move to provide preventive support to families to keep children out of care. Many institutions were closed during that period and foster care programs and family support programs were developed. The 1980s saw the inclusion of sexual abuse and domestic violence in the concerns relating to child protection. The Children and Young Persons Act 1989 brought major changes to child protection. Initially the Act was interpreted to focus on investigation and proof of child abuse and neglect, an interpretation that limited intervention and failed to adequately meet the needs of many families referred to protective services. The Act introduced Permanent Care Orders as an option for children who were unable to return to their birth parents due to the extent of problems within the birth family. In 1985 the Department of Human Services took over the investigative functions for child protection from the Children’s Protection Society initially with a ‘dual track’ system with the police. Later, the Department assumed sole responsibility for investigation of child abuse. Mandatory reporting for specific professionals was introduced in 1993. Recently the Department has initiated a number of Department sponsored programs which have a more child-centred and family-focused approach and a more flexible response to problems of child abuse and neglect. The Department has developed the Victorian Risk Framework (VRF) to guide practice in child protection. Several trends in child welfare are currently evident and of relevance to adoption and permanent care of children. They reflect the need to rethink services to better meet the needs of children in need of care and protection. The trends are: • Re-notification of children is increasing with nearly one quarter of children notified four times or more. • The number of children in out of home care has increased to over 7000. • Foster care and permanent care agencies are experiencing significant recruitment problems. The Department has instituted a number of strategies in response to these trends. 1.2.4 Adoption and permanent care teams Adoption services have been provided by the Department of Human Services and community service organisations since the 1928 Adoption Act was proclaimed. The private and public sectors have played an active role in delivery of services throughout the history of adoption with both Government and voluntary services providing statewide services. In the 1980s with the regionalisation of Departmental services and the impending passage of the Children and Young Persons Act 1989, adoption and permanent care services were regionalised. The regionalisation of adoption and permanent care services was completed in the 1990s with the opening of the Hume, Loddon Mallee and Grampians teams. 14 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide There are now nine regional teams serving eight regions of the Department of Human Services, and one statewide service. • Department teams: – Hume – Barwon-South Western – Eastern Metropolitan – Northern Metropolitan serving North and West Metropolitan Region • Community services organisations teams: – Uniting Care Connections serving Southern Metropolitan Region – Ballarat Child and Family Services serving Grampians Region – Anglicare Western serving North and West Metropolitan Region – Anglicare Gippsland serving Gippsland Region – St Luke’s Child and Family Services serving Loddon Mallee Region • Centacare Catholic Family Services provides a statewide service Each Region refers children who are case planned for permanent care to its regional service. However, children can be placed outside their region in order to provide the optimal permanent placement. The Central Resource Exchange (CRE) facilitates placement of children by providing a register of all eligible families awaiting placement and children in need of permanent care. This service is managed by the head office of the Department of Human Services and is consulted by workers when considering placement of a child. Both the Adoption Act 1984 (Section 21) and the Children and Young Persons Act 1989 (Section 58) provide for the approval of community service agencies to provide adoption and permanent care services. Agencies are required to meet standards consistent with Department programs. The system encourages close cooperation between adoption and permanent care teams. All teams work to the National Standards in Adoption and ensure their practice is consistent with the Department of Human Services’ Adoption and Permanent Care procedures manual. 1.2.5 Function and structure of the Department of Human Services The Department of Human Services provides a wide range of services and funds many community service organisations. It is a complex organisation and it is often difficult to understand the relationship between and within branches within the Department, and the interaction between the Department and CSOs. Although the Department has undergone several reorganisations in recent years, the information regarding the structure and functions of the Department provided in the Child Protection beginning practice learning guide indicates the breadth of services and complexity of organisation. Current organisation structure of the Department can be obtained through the program managers for Adoption and Permanent Care located on the 20th floor of 555 Collins Street. All workers are encouraged to read Section 1.4: The organisational context of the protective services in the Protective Services beginning practice learning guide. Resources Child Protection beginning practice learning guide, Section 1.4. Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 15 Head office of the Department of Human Services The Department of Human Services head office provides a number of services to adoption and permanent care including: • policy • consultancy • training • maintenance of standards • approval of community service agencies. Regional offices of the Department of Human Services A&PC teams provide placement services and consultancy on permanent care issues to the regional offices of the Department of Human services. Although there are substantial regional differences in delivery of services, there are also common organisational structures within all regional offices. Adoption and permanent care fall under Child Protection. Each region has five teams in Child Protection: • Intake team • Response team • Adolescent team • Long term children’s team • Case contracting team. Although at times workers will be consulting with the Protective Services Intake and Response teams or the Adolescent team in relation to their work, workers relate to the Long term children’s team and the Case contracting team more frequently. Prior to placement in permanent care, the Long term children’s team is responsible for the child. After placement the child is generally transferred to the Case contracting team. Each adoption and permanent care team must develop a working relationship with their regional child protection service teams. Regional differences in service delivery and the location of the A&PC team within or outside the regional office play a part in the character of that relationship. Work with protective services is collaborative, and it is important to develop a positive working relationship between permanent care and protective services. Resources Section 3.2: Departmental decision making induction program, and Section 3.11: Supervision of placements, in the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide. 16 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 1.3 Life issues of adoption and permanent care Learning goals • To familiarise workers with life issues of adoption and permanent care for all parties. • To sensitise workers to the need of each party to placement to deal with personal issues. • To understand that all parties to placement experience loss and have a common relationship through their experience of loss. Where a child has been adopted or placed in a family through Permanent Care, each party to the placement—the child, the birth family and the adoptive or permanent care family—face issues that are related to the way the family is formed. These are universal issues and are not themselves indicators of problems. For most persons they are issues that are addressed periodically and are at times felt intensely but are most often not talked about. These issues are experienced as part of adoption or permanent care alongside the joys and pleasures of daily life. Because these issues are universal and all parties to the placement must deal with them, it is essential that the adoptive or permanent care parents and the birth parents be informed of possible issues, and that adoptive and permanent care parents have the capacity to deal with their issues and to assist their children. These issues underpin the reasons for assessment of adoptive and permanent care parents. Life issues of adoption and permanent care revolve around three themes: • loss • search for identity • entitlement. Loss is the common denominator of adoption and permanent care. All parties experience loss. The search for identity and entitlement relate to the losses for each party. The children, the adoptive or permanent care parents, and the birth parents are united through these issues, although expression of the issues may be different between adoption and permanent care. When discussing life issues of adoption or permanent care, there is tendency to over-emphasise the possible negative impacts of the issues. However, the issues of loss and the search for identity and entitlement emerge periodically while people rework their understanding of the issues. The issues are part of a process of living with being part of a non-biological family. Although the issues must be addressed periodically and may at times seem all important, most parties have no need to dwell upon the issues for long periods. Adoption and permanent care issues tend to arise at periods of developmental change that require re-evaluation of understanding for the child, or at times of reminder or trigger events in the lives of adults. Many children and their birth parents, and adoptive or permanent care parents experience these feelings infrequently, whereas other children and their birth parents and adoptive or permanent care parents may go through longer periods of intense review during which adjustments are made. A small number become stuck on these issues and require assistance to resolve them. The positives of adoption and permanent care far outweigh the problems and issues for parties to the placement. The issues are not generally the cause of great distress but are part the experience of every family raising a non-biological child and every birth family related to that child. Resources Silverstein, D. & Kaplan, S., 1982, ‘Lifelong issues in adoption’ (available in the supplement to the Adoption and permanent care learning guide). Brodzinsky, D. M., Schechter, M. D. & Henig, R. M., 1903, Being Adopted: The life long search for self, Anchor Books, New York. Johnston, P., 1992, Adopting after Infertility, Perspectives Press, Indianapolis, Indiana. Verrier, N., 1996, The Primal Wound: Understanding the adopted child, Gateway Press, Baltimore. Armstrong, S. & Slaytor, P., 2001, The Colour of Difference: Journeys in transracial adoption, the Benevolent Society Postadoption Resource Centre, The Federation Press, Sydney. Section 4.4: Identity, in the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide. Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 17 1.3.1 Loss Adoption has been seen as a solution to a series of problems: for adoptive parents their infertility; for the child, the provision of a family; and for the birth parent, the solution to an unwanted or unplanned pregnancy. Permanent care is a solution for children who cannot be raised in their birth family. In reality, all are a way to resolve a crisis but they are imperfect solutions. All parties face losses. Losses can and do help form identity, set values and priorities and expectations, but before a loss can contribute positively to a person’s life, the loss must be mourned. Adoption does not cure infertility, nor does it allow a couple to bypass the fact that they are unable to have biological children. Relinquishment is not just an event in a child’s past. The permanent care parent cannot regain that part of the child’s life that they have missed. Birth parents must live with the decision to relinquish a child and all its implications for themselves and for their future families, whether their children were relinquished voluntarily or removed from their care by Protective Services. The issues for all parties are life-long. Loss is the common denominator of adoption or permanent care. Each party experiences loss and that experience unites them. It is a part of their personal history and it helps make each of them what they are. Parties to adoption or permanent can seek to ignore the losses as acknowledging them can bring into focus the idea that adoption or permanent care is an imperfect solution for every party. They risk becoming too close to the pain. Intellectual and emotional understandings of placement are different. At some point each party encounters the differences and must develop emotional acceptance and understanding of their situation. The issues are a part of adoption or permanent care and create ‘extras’ for each party to deal with emotionally. Parties to an adoption or permanent care have a shared fate. They are united through placement and how they interact, whether in person or through emotional processes, has great significance to each party and their resolution of personal issues. 1.3.2 Search for identity Much has been written about the adopted person’s search for identity and many of the changes in the Adoption Act 1984 were made to assist adopted people in their search. Adopted persons have described their feelings of alienation and disconnection which directly relate to their search for identify and their search for their past. They describe their confusion and curiosity, and their need to know. What is written about adoption also applies to permanent care. A part of identity formation is making connections with the past and accepting the events that have happened. These events are formative and defining. To come to the point of accepting themselves and securely defining ‘who I am’ they must: • accept the birth parent for who they are • mourn the losses they have experienced. The search for identity can be a painful process for a person who must acknowledge and address intense and painful feelings related to relinquishment. The person must reconcile the pain with the positive experiences of the person’s ‘new’ families. Where experiences of abuse and neglect are a part of the past, the person raised in a non-biological family must address even more issues of loss and pain. But the underlying need to know and accept the past is fundamental to feeling whole and positive about oneself. In discussing the search for identity, the focus is generally on the person raised in care. Identity issues, however, are also a part of the birth parents’ and the adoptive or permanent care parents’ experiences. The lives of birth parents change with relinquishment and that change affects their sense of self and their identity. The pregnancy and relinquishment are often unplanned and occur without emotional preparation. Many birth parents express this as ‘I am a parent but have no children.’ Birth parents must incorporate what has happened into their identities and resolve the conflict between what has occurred and that part of their sense of self that has been challenged and altered by the relinquishment. The adoptive parents may face a search for identity. Being parents may have been a part of their identity but becoming parents through adoption or permanent care may not have been a part of their senses of self. They must incorporate the issues of parenting a non-biological child into their senses of self. 18 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 1.3.3 Entitlement The building of entitlement is central to adoption and permanent care: for the adoptive or permanent care parent, the entitlement to be the parent to the child; for the child, the entitlement to belong within the new family; for the birth parent, the entitlement to respect and to be a parent to other children. Adoptive or permanent care parents Without a sense of entitlement, it is difficult for an adoptive or permanent care parent to become a total parent to the child. The parent may keep an emotional distance from the child or find it difficult to make demands on the child, or to set limits. Many of the positive rewards of being a parent are denied to a person who does not feel entitled to be the parent. The parents feel undermined personally and in the roles as parent and fears rejection by the child. Birth parent Relinquishing a child shatters many birth parents’ views of themselves. This can affect many aspects of their lives and how they relate to others. If they feel guilty and shamed, it is difficult to feel entitled to form positive relationships and to accept others’ expressions of caring. For many birth parents, feeling entitled to be loved and to respond to others’ expressions of concern can be impaired, negatively affecting their lives. Persons raised in care: the child A common feeling of children who have been relinquished voluntarily or placed in care is that they are in some way responsible for the decision. Their feelings can inhibit their building strong relationships with adoptive or permanent care parents or birth parents. The blaming of self can support feelings of alienation, not belonging, and difference. It can place a barrier to belonging and feeling entitled to be a part of the ‘new’ family and can place barriers to feeling entitled to be accepted for the person they are. Feeling entitled and the search for identity are strongly connected with the way a person handles loss. To resolve issues of loss a person must mourn the loss. Activity Read Deborah Silverstein and Sharon Kaplan’s ‘Lifelong issues in adoption’ and discuss the issues of loss for each party with you supervisor or in a team meeting. Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 19 1.3.4 Issues for the adopted person Being placed for adoption or permanent care has the capacity to raise many feelings for the child. It can affect the child’s self esteem both negatively and positively, and create additional hurdles for identity development. It provides opportunity and additional challenges associated with understanding the emotions of adoption and permanent care. The adopted person by virtue of being adopted has the task of building his or her identity from the biological family and from the carer family. She or he has the task of understanding the decision for placement not only intellectually but also emotionally. That task requires the child to find a way to understand and accept that he or she has, in emotional terms, been ‘given away’ or ‘rejected’ by the birth mother, the person who is supposed to care for and protect him or her as an infant. The child has lost his or her birth family and cannot rely on either the birth mother or father for protection or care. Intellectual understanding and emotional understanding of adoption or permanent care are often very different. Adopted children may experience a sense of disconnectedness from the past and a sense of confusion and alienation in the present. They may at times experience a profound sense of loss that is pervasive and socially unrecognised. They often feel a sense of isolation and bewilderment sometimes referred to as ‘genealogical bewilderment’ and a loss of completeness with no way to fill the void within. These children may experience intense and generalised anger while seeking to understand their situation. Each developmental task of childhood and adolescence becomes more difficult for the children as they must navigate additional areas with few guideposts. Activity Think about what it would be like to be an adopted person. Define and list some of the issues which might affect the child’s emotional development and leave the child more vulnerable to emotional problems in late childhood and adolescence. Keep the list for reference when discussing placement support. A core issue for the child is trust. If a parent cannot be trusted and counted on to care for a baby, who can be trusted? Can the adoptive mother and father be trusted? What did I do to be rejected? Is there something wrong with me? What must I do to be sure this does not happen again? These are issues that are not easily resolved and issues that may recur in different ways and intensity throughout the child’s life. 20 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 1.3.5 Issues for adoptive or permanent care parents Adoptive or permanent care parents want to have children and in most cases have been very focused on having a biological child before applying to adopt a child. Frequently they have experienced many losses related to infertility which impact on their feelings of self-worth and self esteem and can leave them feeling powerless, out of control, hurt, angry and inadequate. They have lost their dream child and their sense of continuity with the past and the future. They often feel out of step with their friends and peers. Their belief that if you try hard enough you will succeed (a belief prevalent in our culture) has been shattered. Achieving a pregnancy and the birth of a child is out of their control. The infertility treatment may have assaulted the couple’s intimacy and may have taken over their lives to the detriment of other aspects of living. They may see adoption as a way to avoid dealing with the many feelings connected with infertility. The issues of infertility are not issues that are resolved and put behind. Even when the couple has moved to accept their infertility and has made the decision to care for a child for the right reasons, those feelings are a part of the equation. These feelings are sometimes described as ‘an old friend’. The feelings may remain dormant for long periods but make themselves known at times of stress or during significant life events. These feelings may affect the adoptive parents’ feeling of entitlement to be a parent. If a person does not feel entitled to be a parent it is difficult to set limits or to allow the child to explore and develop his or her independence. These feelings may lead the adoptive or permanent care parent to place unrealistic expectations on the child to be someone they cannot be or to achieve in ways alien to the child. They may lead to the adoptive parents placing unrealistic expectations on themselves to be the perfect parent, a task which brings inevitable failure. Activity Think about what it means to be an adopted parent and how some of the issues might be played out in placement. Define and list some of the issues, which might leave the parents more vulnerable. Keep the list for reference when discussing infertility and placement support. Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 21 1.3.6 Issues for the birth parent Birth and relinquishment of a child are not events a birth parent can ever forget. Birth parents can find themselves in a situation where to keep the child is considered wrong by outsiders, and the decision to relinquish the child is not one that is understood. The act of relinquishment creates confusion and a proliferation of negative feelings for the birth parent. It is generally a situation where no decision is right. Each decision has consequences which have some negative impact. The decision to relinquish a child has significant impact on the birth parent’s future life. While it may contribute to the birth parent’s valuing of people, it may also increase the birth parents’ vulnerability to incorporating negative feelings about themselves. Birth parents may experience strong feelings of guilt and a lessening of feelings of self-worth. Birth parents may feel unworthy and may reject themselves. They have lost a child and have no acceptable public means to express their feelings of loss. Where the child has been removed from the birth parent’s care, they may not accept the decision and live the hurt and pain in their daily life. Many birth parents speak of their comfort with the decision to adopt and with the placement but also speak of the continuing pain they feel regarding giving up their child. These difficult feelings recur periodically and may be stronger at certain times such as a child’s birthday or Christmas. Circumstances will change for a birth parent and decisions they made at a particular time may not be the decision they would have made in different circumstances. Activity Think about what it would be like to be a birth parent and how issues of loss might be played out. Define and list some of the issues which might leave birth parents more vulnerable to incorporating negative views of themselves. Keep the list for reference when exploring relinquishment counselling. 22 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 1.3.7 Mourning the loss Loss is the common denominator of adoption and permanent care. The life issues of adoption and permanent care for each party are related to their common experience and to the personal resilience of each person in managing loss. Loss is a universal human experience and one that enriches our understanding and our lives. Before a person can experience the enrichment of loss, the strengthening of confidence in oneself to handle adversity, the re-evaluation of values and priorities, the increased understanding of people and their vulnerabilities and other positive learning, the loss must be mourned. Each person must allow themselves to experience the feelings and to work with these feelings to gain an understanding. This allows the person to accept what has happened and to move on. There are five stages of grief essential to the mourning process (see the diagram below). They are not experienced sequentially but rather people move between sets of feelings as they make adjustments to their loss. It is possible for a person to ‘get stuck’ in any of the first four stages and be unable to move forward without assistance. Figure 1.1: The five stages of grief Denial Acceptance Anger Depression Bargaining Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 23 Denial A person may not believe that the adoption event happened: the child may develop a fantasy which denies the relinquishment; the birth parent might maintain the belief that the placement is temporary. Denial is characterised by shock and some degree of detachment to the event. It is generally the first reaction to a major loss but it often recurs regularly. Anger Anger is a means of confronting the loss and avoiding its pain, at least temporarily. What has happened is viewed as unfair and there is an element of ‘why me.’ Adults and older children generally handle feelings verbally. They connect their anger to an event or circumstance and focus on that. Where there is no explanation for what has happened, as in many cases of infertility, considerable anger can be focused on the unknown. Many adoptive parents indicate that not having something to focus their anger on makes it harder to resolve the anger. For the adopted person, the event generally occurred during a preverbal stage and the child may have difficulty in verbalising the feelings and connecting the feelings to events in their lives. In such situations the anger is generalised and often expressed behaviourally. The birth parent may remain angry and non-accepting of the child being removed from his or her care. Others may be blamed for what has happened and birth parents may be hostile toward workers, their parents and others who may have attempted to assist them. It may be easier to remain angry than to deal with the pain. Bargaining At some point a person feels that the loss can be changed or not experienced, if he or she acts in a certain way. This is a universal feeling. Most people recognise that their current actions cannot change the past but it is possible to get stuck in this phase believing that they can avoid experiencing loss if they can only act in a certain manner. Silverstein and Kaplan described persons stuck in this phase as ‘people pleasers’ but it may take on other characteristic. For instance, a child may try to be so good that he or she cannot be sent away or the adoptive or permanent care parent may try to be perfect so that people will not know that they feel inadequate. Depression There is good reason for depression following the experience of significant loss. Depression with its intense sadness embodies all the negative feelings experienced following the loss. As one adjusts, depression lifts and does not rule the life and emotions of the person. Acceptance Acceptance is an often-misunderstood term. It does not mean that a person does not remember or experience ongoing sadness and feelings which have a strong element of distress. It means that the feelings connected with the loss do not determine the person’s outlook on life, or their behaviour and response to situations. The person can function and experience the pleasures and pains of life and learn from the experience they have been through. Until a loss can be mourned, a person is not in a position to move forward. If mourning is incomplete, people may become stuck, and their experience determines their actions without them being in a position to control their behaviour. Learning from the experience enriches one’s life. The task for each party is to reach the point where they can find a way to understand the loss and where they can use the experience to enrich their lives rather than relive the pain. Mourning for most people is a process which has an end. The loss becomes a part of their lives and something they can learn from. The feelings are there, but no longer overwhelm or direct the person. The person can acknowledge the loss and acknowledge the richness in their lives. They can use their experience to evaluate ‘who am I’ and to set value and priority on their lives. 24 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide Activity Read the Silverstein and Kaplan article ‘Lifelong Issues in Adoption’ and review the table ‘Seven core issues in adoption’ attached to the article. The article is available in the supplement to the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide. Choose one issue. Try to imagine yourself as a child, a birth parent, or an adoptive or permanent care parent being controlled by that issue. How do you think you would react to those around you? Discuss with your supervisor. When you attend the adoption and permanent care workshops, identify the areas relating to loss that are covered during the workshops. Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide 25 1.4 Checklist of things to do In the first six weeks 1 View the videos: – Building New Families: Permanent care, 2004, Centacare Catholic Family Services, Triple A Productions, Melbourne. – A Challenge Worth Taking: Growing up in permanent care, 2003, Centacare Catholic Family Services, Triple A Productions, Melbourne. – You Can Do It, 1998, Anglicare Victoria, Tapeflex, Melbourne. – These videos were produced by Adoption and Permanent Care and are available in your agency. – Identify four issues from each video to discuss with your supervisor. 2 Arrange a visit to: – Adoption and Family Records Service (AFRS) of the Department of Human Services or the Adoption Information Service (AIS) of your agency – VANISH (Victorian Adoption Network for Information and Self Help) – MacKillop Heritage and Information Service (provides information to persons placed in the Catholic Children’s homes) – a foster care agency in your region – a case contracting team in your region – the Disability Services Initiative in Adoption and Permanent Care (DISAPC), Head Office, Department of Human Services. 3 Meet with Administration staff to learn the record keeping procedures of your agency. As soon as can be arranged 1 Attend a Link Meeting—Read reports on child and families to be presented before Meeting. 2 Attend an Applicant Assessment Committee Meeting (AAC)—Read the report and prepare questions regarding the applicants prior to the meeting. 3 Attend a case planning meeting—Read the permanent care worker’s report prior to meeting. 4 Attend a permanent care hearing at a children’s court with another worker—Observe pre-hearing negotiations and as well as a contested hearing if possible. Prepare questions ahead of each visit. Discuss what you have learned with your supervisor after the visit. Wherever possible, make these visits with other new starters or other workers in your agency. 5 Observe an experienced worker (your supervisor will make the necessary arrangement). 6 Obtain a copy of your agency Privacy Policy and Procedures. Discuss the policy with your supervisor. 7 Attend workshops: – Adoption Information Program—The programs are held periodically through Head Office (Department of Human Services). – Adoption Education Workshop—The Education programs are organised through Head Office (Department of Human Services) for regional teams and are held several times each year. Centacare CFS holds two adoption education programs each year. Contact both sources for the next workshop. Complete Section 1.3: Life issues of adoption and permanent care of the Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide and read section 7, page 45 of the Department of Human Services Adoption and Permanent Care procedures manual before attending the workshops. Note how the issues of loss are addressed throughout the workshop. 26 Adoption and Permanent Care learning guide Each couple receives a resource pack during the workshop. You should read all the handouts provided to the prospective applicants. – Permanent Care Information Program—Each Regional Team and Centacare runs Information Programs regularly. – Permanent Care Education Workshop—Regional teams and Centacare run Education Workshops periodically. Read Section 7, pages 42–44 of the Department of Human Services Adoption and Permanent Care procedures manual before attending the workshop. Each prospective applicant receives a resource pack at the workshop. You should read all the handouts provided to prospective permanent care parents by your agency. 8 Read Fahlberg, V., 1994, A Child’s Journey through Placement, BAAF, London (available through the Department’s library if your agency does not have a copy).