primary health care nursing in new zealand - ResearchSpace

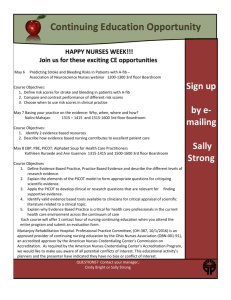

advertisement