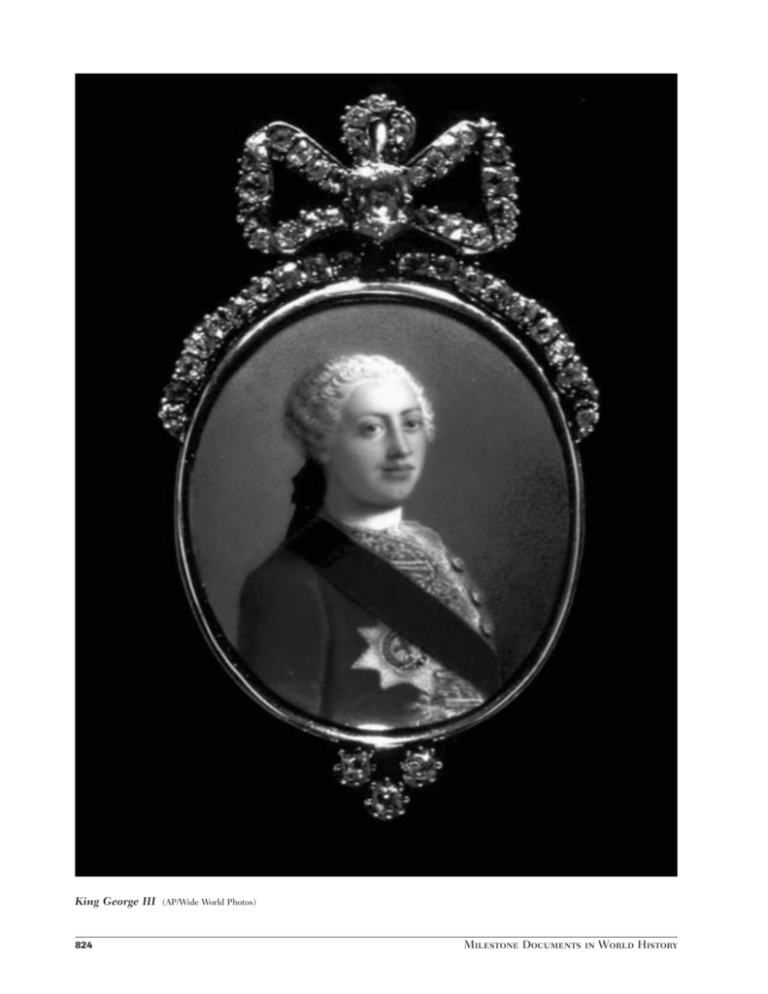

King George III

824

(AP/Wide World Photos)

Milestone Documents in World History

1793

Qianlong’s Letter to George III

“ My capital is the hub and centre about which all quarters of the globe revolve.”

Overview

Arguably the earliest communication

between a monarch of China and the ruler

of a European country, Qianlong’s letter to

George III was the official response to Lord

George Macartney’s mission, sponsored by

the British East India Company in cooperation with the British government, to

secure diplomatic relations and improved trade conditions

with the Qing Dynasty. From its establishment in 1600, the

British East India Company was a major exporter of silk,

tea, porcelain, and lacquerware from China to England and

the rest of Europe. Beginning in the mid-eighteenth century, the East India Company also attempted to sell English

and European goods, most of them manufactured products, to China in order to offset a mounting trade deficit.

Before the Macartney embassy, the company had sent

emissaries to China, hoping to broaden trade relations and

gain better access to the Chinese market. None of them

was successful.

It was in this context that Lord Macartney undertook

his mission. Unlike his predecessors, he was permitted to

enter the Qing palaces in Beijing and elsewhere, have an

audience with the Qing emperor Qianlong and his confident Heshen, and present George III’s letter to the emperor. None of this had been achieved before. But in the end

Macartney failed to realize the goals set by the government

and the East India Company for his embassy. Considering

himself to be the ruler of the “central country,” at the time

the richest and most powerful in the world, Emperor Qianlong rejected all of Macartney’s requests. Nor did the

emperor think that a small maritime kingdom located several thousand miles away was a force deserving his attention and concern. Little did he know that all this was to

change in about a half century.

Context

Several factors prompted the British East India Company and the British government to launch the Macartney

embassy to seek diplomatic contact with Qing China, occa-

Qianlong’s Letter to George III

sioning the letter exchange between George III and Emperor Qianlong. First, during the second half of the eighteenth

century the Industrial Revolution was well under way and

was playing an increasingly important role in shaping

British foreign policy. Propelled by the British desire for

raw materials and new markets, British foreign policy

became more and more colonialist and expansionist. Having won the Seven Years’ War (1756 1763), the British

began to establish their colonial empire around the

world a drive that continued despite the later loss of the

North American colonies in the American Revolution.

Indeed, to some extent, this loss may have served to deepen the English craving to seek compensations elsewhere.

Second, the eighteenth century was an era of exploration

and discovery. Even as Britain was dispatching the Macartney mission to China, it was beginning to expand its holdings in Canada, India, and Australia. Little wonder, then,

that among Macartney’s retinue were botanists, artists, and

cartographers. The embassy thus was both a diplomatic

mission and a voyage of discovery; as the former realized an

economic interest, the latter showed a curiosity for firsthand knowledge of the mysterious Far East. Born and

raised in Northern Ireland, George Macartney, who was

created Viscount Macartney of Dervock right before his

departure, was regarded as the best available diplomat and

administrator to fill the post, because he had had experience dealing with Catherine the Great of Russia, another

despotic ruler.

The third and perhaps most immediate reason for

Britain’s desire to secure diplomatic relations with China

was that though the English trade with China would not be

formally established until the early eighteenth century, that

trade was nevertheless quickly increasing in importance.

Throughout the seventeenth century, for example, tea

drinking had gradually become a national habit in England,

generating a strong demand for expanded trade with China.

Indeed, according to Jonathan Spence, “by 1800, the East

India Company was buying over 23 million pounds of

China tea at a cost of £3.6 million” (p. 122). Between 1660

and 1700 the East India Company had made attempts to

establish a factory in the provincial capital of Guangzhou

(known in English as Canton) and elsewhere, but to no

avail. By 1710 English merchants were trading regularly in

825

Time Line

1600

■

December 31

The East India

Company is

established by

charter and

soon becomes a

major trader

with the Indian

Subcontinent

and the Orient.

1644

■

The Manchus

found the Qing

Dynasty, or

Empire of the

Great Qing.

1683

■

The Qing, under

Emperor Kangxi,

unify the whole

country by

defeating

various forces in

South China,

Tibet, and

Taiwan.

1736

■

Emperor

Qianlong

ascends the

throne.

1760

■

The Qing

Dynasty

imposes the

Canton System

to control trade

in China.

■

October 25

King George III

ascends the throne

of England.

■

February 10

The Treaty of

Paris is signed,

ending the

Seven Years’

War and

establishing

Britain’s

dominance of

most colonies

outside Europe.

1763

826

Guangzhou, but their activities were straitjacketed by the

Canton System imposed by the Qing Dynasty in 1760. By

sponsoring the Macartney embassy, the company hoped,

through diplomacy, to circumvent the Canton System and

other Qing governmental regulations and gain direct access

to Chinese goods.

The Qing Dynasty was not completely disinterested in

foreign trade and the profit it generated. Although Emperor Qianlong forcefully rejected Macartney’s requests for

expanded trade, the Qing court reaped handsome customs

revenue from seaborne foreign commerce in certain ports

along the coast. This stood in stark contrast to the policy of

its predecessor, the Ming Dynasty (1368 1644), which

during the early fifteenth century was known for launching

stupendous maritime expeditions that reached the eastern

and southeastern coasts of Africa. But from the time of the

mid-Ming, troubled by piracy, the dynasty resumed its policy of haijin, or “coastal clearance,” forbidding the Chinese

to sail into the sea and foreign merchants to come ashore.

The Qing rulers continued this “sea ban” policy, though for

a different reason to prevent the recuperation of the

remaining Ming forces that had been active along the coast

and in Taiwan. After Emperor Kang Xi, the dynasty’s second and perhaps most able ruler, had pacified the coastal

regions in 1683, he lifted the ban on overseas trade. Ironically, it was during Emperor Qianlong’s reign that the sea

ban was greatly relaxed, giving rise to the Cohong, a merchant guild that gradually gained a monopoly, authorized

by the Qing government, on trading with Western merchants. The Cohong thus became a core agency in the

Canton System, which helped put overseas trade under the

direct control of both the provincial government and the

central government’s Ministry of Revenue. The Canton

System was aimed at delimiting foreign trade and exploiting its income for the Qing court.

While Emperor Qianlong showed interest in foreign

trade, he was clearly not ready to expand it to the extent

desired by the British. The Qing was founded by the

Manchus, a nomadic group and an ethnic minority that

had arisen originally in Manchuria, today’s Northeast

China. After replacing the Ming Dynasty, the Manchu

rulers quickly adopted a policy of presenting themselves as

the legitimate successors of the Ming imperial realm. In

economic terms, this meant that the Qing continued the

traditional emphasis on agricultural development, one that

had been in place for two millennia. Like the Ming and

most of its predecessors, the Qing considered itself politically and ideologically the owner of the Central Country

(Zhongguo, or “Middle Kingdom”), an undisputed center of

civilization in the world and one that radiated its cultural

influence to the surrounding regions. All this was reflected

in the practice of the entrenched “tributary system” that

the Qing had inherited from its predecessors in managing

relations with its neighbors. Under this system, it was

assumed that uncultured neighboring barbarians would be

attracted to China and would be transformed by Chinese

culture. The Chinese ruler would show compassion for foreign emissaries. In Emperor Qianlong’s era, these “tribu-

Milestone Documents in World History

Qianlong’s Letter to George III

Time Line

1760s

■

A series of

inventions in cotton

spinning are

patented in Britain,

propelling the

expansion of its

textile industry and

sparking interest in

acquiring silk and

other fabrics from

China.

1780s

■

James Watts

improves the

design of the

steam engine, a

landmark event

in the Industrial

Revolution and

one that led to

advances in

oceangoing

vessels.

1792

■

September

The British East

India Company and

British government

dispatch Lord

George Macartney

as ambassador to

China for

developing trade

and diplomatic

relations with the

Qing Empire, where

he remains until

1794.

1793

■

September 14

Macartney

presents a letter

from George III

to Emperor

Qianlong,

seeking to

secure

diplomatic

relations and

improved trade

conditions with

Qing China.

■

October 3

Emperor Qianlong

summons

Macartney to his

court and tenders

his reply to King

George’s letter.

Milestone Documents

tary states” could be found not only in today’s Korea, Vietnam, Burma, and Thailand but also in parts of Russia, the

Netherlands, and Portugal.

Compared with the Russians, who had established an

ecclesiastical mission in Beijing, and the Portuguese, who

had held Macao as their enclave, the British were latecomers in seeking a relationship with Qing China. However,

powered by the raging Industrial Revolution, this nation of

just eight million compared with 330 million in Qing

China began to sense that they represented the burgeoning great power in the world. This sentiment was evident in

the instructions given by Henry Dundas, the home secretary of the British Government, to Lord Macartney:

1. to negotiate a treaty of commerce and friendship and

to establish a resident minister at the court of Qianlong;

2. to extend British trade in China by opening new ports

where British woolens might be sold;

3. to obtain from China the cession of a piece of land or

an island nearer to the tea- and silk-producing area than

Guangzhou, where British merchants might reside the whole

year and where British jurisdiction could be exercised;

4. to abolish the existing abuses in the Canton System

and to obtain assurances that they would not be revived;

5. to create new markets in China for British products

hitherto unknown, such as hardware; and

6. to open Japan and Vietnam to British trade by means

of treaties.

The nature and scope of these charges suggest that the

British government hoped to attain much more from their

contact with the Chinese than had been accomplished by

other Europeans. Most important, they wanted their country to be treated as an equal by the Qing ruler. Lord

Macartney intended to show the Chinese that a new power

had been born in the West.

Steam-driven vessels would indeed bring the English

close to the Chinese shore and deliver a serious blow to

their empire in the mid-nineteenth century. But Emperor

Qianlong did not foresee this. After all, the Qing Dynasty,

from the time of its founding in the mid-seventeenth century and until the time of Qianlong, had stood undefeated

in all the wars it had fought with its enemies. The emperor

was willing to show his compassion for, or even “cherish,”

the visit of an embassy from afar, especially one offering

belated congratulations for his eightieth birthday and presenting tribute to his Celestial Empire. But he was uninterested in anything beyond that, let alone in any notion of

treating the British as equals.

On September 14, 1793, a year after departing from

London, Macartney and his retinue were received by the

emperor at Rehe, a Qing summer palace north of Beijing.

As he presented King George III’s letter to Qianlong,

Macartney is said to have knelt on one knee, as if he were

being received by his king, though he omitted kissing the

emperor’s hand. Macartney and his associates denied that

they ever performed kowtow (which required bending both

knees) at the Qing court, but new scholarship reveals that

while the Chinese ministers were performing the kowtow

on one or two other occasions, prostrating their bodies and

827

Time Line

1796

■

Emperor Jiaqing

ascends the

throne.

1799

■

Emperor

Qianlong dies.

poems and essays in Chinese and was a patron of an ambitious ten-year bibliographic project known as the Four

Treasuries (Siku quanshu), the avowed aim of which was to

cull, catalog, and abstract all existing books. The study of

Chinese Confucian culture, in the form of “evidential

learning” an intellectual trend of the Qing period that

emphasized an empirical approach to the understanding of

Confucian classics flourished.

Explanation and Analysis of the Document

1820

■

January 29

George III dies.

1839

■

The First Opium

War begins.

knocking their foreheads on the ground, the British also

knelt on both knees and bowed their heads to the ground.

Thus, scholars differ in their reading and interpretation of

the sources regarding the kowtow ritual. Despite this, most

of them seem to agree that even if the English, or Macartney, had followed the usual ritual in meeting Emperor

Qianlong, it would not have altered their mission’s outcome the emperor would still have rejected their

requests. For though the Qing court delighted in profiting

from tea, silk, lacquer, and porcelain exports to Europe,

such things remained luxurious and therefore peripheral to

their agriculture-based economy.

After he presented King George III’s letter to Emperor

Qianlong on September 14, 1793, Lord Macartney did not

receive a reply until October 3, when he and his assistant

were ushered into Beijing’s Forbidden City and asked to

genuflect before the scroll that represented the emperor’s

rejoinder. In fact, Qianlong’s response had been ready

since September 22. Indeed, Qing court documents reveal

that the letter had been drafted as early as July 30 and had

been submitted to Emperor Qianlong on August 3, more

than six weeks before King George III’s letter was even

delivered. In other words, the failure of the British mission

to establish trade and diplomatic relations was “inevitable

from the outset” (Peyrefitte, p. 288). Nevertheless, Macartney’s omitting to kneel on both knees when he delivered his

king’s requests to the emperor apparently had served to

toughen the letter’s tone in rejecting these requests. As an

imperial edict, Qianlong’s response was written in classical

Chinese and rendered into Latin by Jesuit missionaries.

Next, the embassy drafted an English summary of the Latin

translation, erasing any trace of offensive and condescending phrases. Neither of these texts has survived. The letter

exists today only in abridged versions.

◆

About the Author

Emperor Qianlong was born Hongli, the fourth son of

Emperor Yongzheng, in 1711. Qianlong was his reign

name, and he would not take it until he assumed the

throne of the empire. In imperial China, members of the

upper class usually had several names for difference occasions. The name given by the parents was used strictly

within the family. Emperors had a reign name because, out

of deference, no one outside the family was supposed to

use his given name. Qianlong was the fourth emperor of

the Qing Dynasty, and his reign which began in 1736 and

ended officially in 1795 (though he remained in power

until his death in 1799) was the longest in the dynasty,

representing its heyday. Among the emperor’s many accomplishments was the acquisition of a huge territory in the

northwest, known as Xinjiang, or “New Territory,” which

doubled what was then China’s territory. Under Qianlong’s

rule, the population experienced a boom, attesting to the

vibrancy of the economy.

Besides being an able administrator, Emperor Qianlong

was a cultural dilettante. He penned a great number of

828

Paragraphs 1–6

In the first two paragraphs, Emperor Qianlong politely

acknowledges the effort by King George III to send a diplomatic mission, which he interprets as a “desire to partake

of the benefits of our civilisation.” He delights in the fact

that the mission was sent to congratulate him on the

anniversary of his birthday. In return for this friendly gesture and for the mission’s gifts (which he regards as tributes), the emperor informs King George that he has shown

his generosity by personally meeting the embassy and treating them with presents and banquets.

In the next four paragraphs, the emperor proceeds to the

first important issue: rejecting the embassy’s request to

establish a diplomatic residency in Beijing and denying English merchants permission to travel and trade freely in the

country. His reasons are three: First, drawing perhaps on

the experience of the Jesuit missions, the emperor cites the

historical precedent that once a European was permitted to

live in China, he then would be expected to adopt the Chinese way of life and would be forbidden to return home.

This would not suit the goal that the diplomatic residency

hoped to achieve. Second, the emperor suggests that there

is nothing wrong with the Canton System of managing and

Milestone Documents in World History

Milestone Documents

Seals belonging to the Qianlong Emperor

(Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D C Anonymous gift, F1978 51a-f)

controlling trade with the Europeans, and he refuses to

alter it to accommodate the English request that a resident

diplomat be allowed to direct English trade with China. He

asks, “If each and all [Europeans] demanded to be represented at our Court, how could we possibly consent?” a

reflection of the historical reality that tributary missions

from foreign lands would remain in China for no more than

several months. It likewise suggests that although the

emperor was aware that Europe comprised many nations,

he did not know that diplomatic residence had become a

Qianlong’s Letter to George III

common practice among them. Of course, knowing would

almost certainly not have altered his judgment: Qianlong

was quite confident that China’s “ceremonies and code of

laws” were superior to those of the Europeans.

This sense of cultural superiority stands as Qianlong’s

third reason for dismissing the English request. He tells the

king that he believes that even if the English envoy “were

able to acquire the rudiments of our civilisation, you could

not possibly transplant our manners and customs to your

alien soil.” Considering himself to be the ruler of a superior

829

civilization occupying the center of the universe, the emperor makes it clear to King George that if he permits certain

trade with the English, it is because he wants to bestow

grace and extend friendship to a foreign nation, for “we possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures.”

nations would seek the same, which he regards as dangerous, for “friction would inevitably occur between the Chinese and your barbarian subjects.” In the same spirit, he

sees that this permission would invariably expand their

contacts with the Chinese people.

◆

◆

Paragraphs 7 and 8

These paragraphs explain the emperor’s refusal to expand

trade with the English. They begin with a similar acknowledgment, only now in a somewhat more condescending

tone. Noting King George’s interest in seeking to “come into

touch with our converting influence” and his “respectful

spirit of submission,” the emperor informs the king that he

has reciprocated with “the bestowal of valuable presents.”

The emperor continues to explain somewhat haughtily

to the English king why he is forced to reject his emissary’s

requests. The emperor sees the proposal to expand trade

and bypass the Cohong as a violation of the existent practice, which he considers impeccable. Such a request, if

granted, would set a “bad example” for other nations. Thus,

he not only wanted his ministers to educate the embassy

about the rules of his empire but also ordered them to

arrange departure for the embassy.

◆

Paragraphs 9–12

The next four paragraphs address Macartney’s detailed

requests for gaining access to the Chinese market, which

include setting facilities for assisting English ships in port

cities other than Xiamen (“Aomen” in the document); establishing a merchant repository in Beijing, the Qing capital;

allowing English merchants to reside on a small island near

Zhoushan (“Chusan”); and gaining them a residential compound in the city of Guangzhou (“Canton”). The emperor

rejects all of these requests because he considers the established Cohong system the best way to handle foreign trade.

Specifically, he states that the port city Xiamen, located in

southeastern China, is the most ideal geographic location for

a merchant repository because it is “near to the sea.” More

important, it was where the Cohong ran its operation by

which the Qing Dynasty controlled and contained trade with

the West. The emperor regards the request for merchant residence and repository as an infringement on the empire’s territorial integrity. But in doing so, he has to explain why the

Russians were granted such a facility in Beijing. Although his

answer is hardly persuasive, it is nevertheless unequivocal:

“The accommodation furnished to them [the Russians] was

only temporary.” He underscores the fact that his dynasty

restricts the movement of foreigners when he says that they

have never been allowed “to cross the Empire’s barriers and

settle at will amongst the Chinese people.”

In responding to the request for an island near

Zhoushan where merchants could reside and warehouse

goods, the emperor is unequivocal that it would set up an

“evil example.” He asks how he could comply with such

requests from other nations. The same argument is applied

to the request for a site in Guangzhou. If he allows the

English to gain such a privilege, then other European

830

Paragraphs 13 and 14

The next two paragraphs deal with issues related to tax

and tariff. One of the major reasons for the English government to send the Macartney mission to China was to seek,

in modern language, a “most favored nation status” for

Britain. This status would reduce duties and tariffs levied by

Qing China on English merchandise. Emperor Qianlong

also rejects these requests. As before, he does so by stressing

the issue of equality. As he puts it, he does not want to “make

an exception in your case” lest the principle of equality exercised by the Qing court in managing foreign trade be violated. Yet what lurks beneath this seemingly grand reason is his

refusal to make any changes to the existing Cohong system.

◆

Paragraph 15

The next paragraph, denying the request to conduct missionary activities in China, offers a glimpse into the emperor’s mindset regarding cultural exchange in general and his

recalcitrant attitude toward managing overseas trade in particular. Although he does not denigrate Christianity, he

clearly regards the Chinese moral system as superior. He

describes how this system was established from time immemorial and how it has been religiously observed by generations of Chinese. He reminds the king that Europeans present in China are prohibited from preaching their religion to

his subjects. This explanation was consistent with the policy instituted in the early eighteenth century by Emperor

Kangxi Emperor Qianlong’s much-loved grandfather in

the wake of the Rites Controversy, which essentially forbade

Christian missionaries from proselytizing the Chinese.

◆

Paragraph 16

Having rejected all of the requests “wantonly” made by

the Macartney embassy on behalf of King George III,

Emperor Qianlong concludes his letter by blaming Lord

Macartney and not the king himself for entertaining and presenting such “wild ideas and hopes.” Even if the king were

somewhat involved, the emperor writes, it was out of ignorance and innocence; he assumes that King George III “had

no intention of transgressing [Qing dynasty regulations].” He

goes on to deliver a stern warning to King George III: If the

British government persists in pursuing those proposals, it

and its emissaries will face severe punishments. “Tremblingly obey and show no negligence!” he tells the king.

Audience

Emperor Qianlong’s letter was, first and foremost,

addressed to the king of England, George III. Although he

wrote as one monarch to another, Qianlong was issuing a

response in the form of an “imperial edict.” He was placing

Milestone Documents in World History

“

Essential Quotes

Milestone Documents

“As to your entreaty to send one of your nationals to be accredited to

my Celestial Court and to be in control of your country’s trade with

China, this request is contrary to all usage of my dynasty and

cannot possibly be entertained.”

(Paragraph 3)

“How can our dynasty alter its whole procedure and system of etiquette,

established for more than a century, in order to meet your individual views?”

(Paragraph 4)

“Swaying the wide world, I have but one aim in view, namely, to maintain

a perfect governance and to fulfil the duties of the State: strange and costly

objects do not interest me.”

(Paragraph 5)

“My capital is the hub and centre about which all quarters of the

globe revolve.”

(Paragraph 10)

”

“Ever since the beginning of history, sage Emperors and wise rulers have

bestowed on China a moral system and inculcated a code, which from

time immemorial has been religiously observed by the myriads of my

subjects. That has no hankering after heterodox doctrines.”

(Paragraph 15)

himself on a quite different footing. Although Qianlong was,

in a sense, having his own “audience” with the British king,

his condescending tone was that of a superior. King George,

as the intended recipient, would have been unlikely to have

received the letter in the spirit in which it was offered. We

do not know, however, whether the letter was ever delivered.

The more immediate audience for the emperor’s letter

was Lord McCartney and his embassy. Written in classical

Chinese, the letter had first to be translated by Jesuit missionaries into Latin and then by the embassy into English.

The embassy was concerned enough about the language to

erase any trace of offensive and condescending phrases.

Macartney wrote of the event in his journal, where he

describes being received at the palace by the First Minister,

Qianlong’s Letter to George III

but without the usual graciousness and with a certain constraint. Later, when high officials of the court delivered the

letter itself to him at home, Macartney comments that from

their manner it had become clear that the Chinese wanted

the British embassy to leave. He does not remark on the

contents of the letter itself. In early 1794 Macartney sailed

for home, disappointed that his mission had failed.

Impact

In response to King George’s request for broadening trade

and bettering diplomatic relations, Emperor Qianlong wrote

his letter in the form of an imperial edict, explaining in detail

831

how and why he would not grant such a request. The emperor wanted to tell the English king how ignorant he was about

the magnificence of the Chinese Empire and how improper

his request was. However, we are unsure whether Lord

Macartney actually delivered Emperor Qianlong’s letter to

King George. Hence, we do not know King George’s reaction. In other words, whatever the emperor’s intention was in

writing the letter, it did not have the intended impact.

This first communication between the Qing emperor of

China and the king of England was not entirely fruitless.

Although George Macartney failed in his diplomatic mission to open the door to British trade with China, he was

more successful in his voyage of discovery. During his sixmonth sojourn in China he made careful and detailed

observations of the country in his journal, as did some of

other members in the embassy. Their portrayal of the Chinese as a stubborn and superstitious people and the Qing

Dynasty as a backward-looking empire, uninterested in

change and novelty, eventually altered the more positive

image of China in the European mind generated by the

Jesuits’ writings and by the philosophes. Instead, Macartney

and his assistants were convinced that to change China “the

effort required would be superhuman and that violence

could someday be necessary” (Peyrefitte, p. 541). Violence

was indeed used in the First Opium War of 1839 1842.

. “Tradutore, Traditure, A Reply to James Hevia.” Modern China

24, no. 3 (July 1998): 328 332.

Gillingham, Paul, “The Macartney Embassy to China.” History

Today 43, no. 11 (November 1993): 28 34.

Hevia, James H. “Postpolemical Historiography: A Response to

Joseph W. Esherick,” Modern China 24, no. 3 (July 1998): 319 327.

■

Books

Cranmer-Byng, J. L., ed. An Embassy to China: Being the Journal

Kept by Lord Macartney during his Embassy to the Emperor Ch’ienlung, 1793 1794. St. Claire Shores, Mich.: Scholarly Press, 1972.

Hevia, James H. Cherishing Men from Afar: Qing Guest Ritual and

the Macartney Embassy of 1793. Durham, N.C.: Duke University

Press, 1995.

Peyrefitte, Alain. The Collision of Two Civilizations: The British

Expedition to China in 1792 4, trans. Jon Rothschild. Hammersmith, U.K.: Harvill, 1993.

Spence, Jonathan. The Search for Modern China. New York: W. W.

Norton, 1990.

Q. Edward Wang

Further Reading

■

Articles

Esherick, Joseph. “Cherishing Sources from Afar.” Modern China

24, no. 2 (April 1998): 135 161.

Questions for Further Study

1. The British East India Company was a private corporation, but during the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century it represented a projection of British imperial power in Asia and thus became a governing power.

How and to what extent was the company able to achieve this goal?

2. Why was China such an important market for Great Britain? What economic reasons did Great Britain have

for strengthening trade relations with China?

3. To what extent did cultural differences between China and England lead to the Chinese emperor’s rejection of

King George III’s proposal? What specific cultural practices in China influenced Qianlong’s response to King George?

4. Qianlong rejected out of hand every one of Britain’s proposals. What do you believe was the underlying reason for his refusal even to entertain the possibility of agreeing to any of these proposals?

5. Compare and contrast Qianlong’s Letter to King George III with Lin Zexu’s “Moral Advice to Queen Victoria,”

written less than four decades later in 1839. Did the later letter suggest any advances in relations between Great

Britain and China, or was China still “closed” to Britain and its trading goals?

832

Milestone Documents in World History

Document Text

You, O King, live beyond the confines of many

seas, nevertheless, impelled by your humble desire to

partake of the benefits of our civilisation, you have

dispatched a mission respectfully bearing your

memorial. Your Envoy has crossed the seas and paid

his respects at my Court on the anniversary of my

birthday. To show your devotion, you have also sent

offerings of your country’s produce.

I have perused your memorial: the earnest terms

in which it is couched reveal a respectful humility on

your part, which is highly praiseworthy. In consideration of the fact that your Ambassador and his

deputy have come a long way with your memorial

and tribute, I have shown them high favour and have

allowed them to be introduced into my presence. To

manifest my indulgence, I have entertained them at

a banquet and made them numerous gifts. I have

also caused presents to be forwarded to the Naval

Commander and six hundred of his officers and

men, although they did not come to Peking, so that

they too may share in my all-embracing kindness.

As to your entreaty to send one of your nationals

to be accredited to my Celestial Court and to be in

control of your country’s trade with China, this

request is contrary to all usage of my dynasty and

cannot possibly be entertained. It is true that Europeans, in the service of the dynasty, have been permitted to live at Peking, but they are compelled to

adopt Chinese dress, they are strictly confined to

their own precincts and are never permitted to

return home. You are presumably familiar with our

dynastic regulations. Your proposed Envoy to my

Court could not be placed in a position similar to

that of European officials in Peking who are forbidden to leave China, nor could he, on the other hand,

be allowed liberty of movement and the privilege of

corresponding with his own country; so that you

would gain nothing by his residence in our midst.

Moreover, our Celestial dynasty possesses vast

territories, and tribute missions from the dependencies are provided for by the Department for Tributary

States, which ministers to their wants and exercises

strict control over their movements. It would be

quite impossible to leave them to their own devices.

Supposing that your Envoy should come to our

Court, his language and national dress differ from

Qianlong’s Letter to George III

Milestone Documents

Qianlong’s Letter to George III

that of our people, and there would be no place in

which to bestow him. It may be suggested that he

might imitate the Europeans permanently resident in

Peking and adopt the dress and customs of China,

but, it has never been our dynasty’s wish to force

people to do things unseemly and inconvenient.

Besides, supposing I sent an Ambassador to reside in

your country, how could you possibly make for him

the requisite arrangements? Europe consists of many

other nations besides your own: if each and all

demanded to be represented at our Court, how could

we possibly consent? The thing is utterly impracticable. How can our dynasty alter its whole procedure

and system of etiquette, established for more than a

century, in order to meet your individual views? If it

be said that your object is to exercise control over

your country’s trade, your nationals have had full liberty to trade at Canton for many a year, and have

received the greatest consideration at our hands.

Missions have been sent by Portugal and Italy, preferring similar requests. The Throne appreciated

their sincerity and loaded them with favours, besides

authorising measures to facilitate their trade with

China. You are no doubt aware that, when my Canton merchant, Wu Chao-ping, was in debt to the foreign ships, I made the Viceroy advance the monies

due, out of the provincial treasury, and ordered him

to punish the culprit severely. Why then should foreign nations advance this utterly unreasonable

request to be represented at my Court? Peking is

nearly two thousand miles from Canton, and at such

a distance what possible control could any British

representative exercise?

If you assert that your reverence for Our Celestial

dynasty fills you with a desire to acquire our civilisation,

our ceremonies and code of laws differ so completely

from your own that, even if your Envoy were able to

acquire the rudiments of our civilisation, you could not

possibly transplant our manners and customs to your

alien soil. Therefore, however adept the Envoy might

become, nothing would be gained thereby.

Swaying the wide world, I have but one aim in

view, namely, to maintain a perfect governance and

to fulfil the duties of the State: strange and costly

objects do not interest me. If I have commanded that

the tribute offerings sent by you, O King, are to be

833

Document Text

accepted, this was solely in consideration for the

spirit which prompted you to dispatch them from

afar. Our dynasty’s majestic virtue has penetrated

unto every country under Heaven, and Kings of all

nations have offered their costly tribute by land and

sea. As your Ambassador can see for himself, we possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or

ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures. This then is my answer to your request to

appoint a representative at my Court, a request contrary to our dynastic usage, which would only result

in inconvenience to yourself. I have expounded my

wishes in detail and have commanded your tribute

Envoys to leave in peace on their homeward journey.

It behoves you, O King, to respect my sentiments

and to display even greater devotion and loyalty in

future, so that, by perpetual submission to our

Throne, you may secure peace and prosperity for

your country hereafter. Besides making gifts (of

which I enclose an inventory) to each member of

your Mission, I confer upon you, O King, valuable

presents in excess of the number usually bestowed

on such occasions, including silks and curios a list

of which is likewise enclosed. Do you reverently

receive them and take note of my tender goodwill

towards you! A special mandate.

You, O King, from afar have yearned after the

blessings of our civilisation, and in your eagerness to

come into touch with our converting influence have

sent an Embassy across the sea bearing a memorial.

I have already taken note of your respectful spirit of

submission, have treated your mission with extreme

favour and loaded it with gifts, besides issuing a

mandate to you, O King, and honouring you with the

bestowal of valuable presents. Thus has my indulgence been manifested.

Yesterday your Ambassador petitioned my Ministers to memorialise me regarding your trade with

China, but his proposal is not consistent with our

dynastic usage and cannot be entertained. Hitherto,

all European nations, including your own country’s

barbarian merchants, have carried on their trade

with our Celestial Empire at Canton. Such has been

the procedure for many years, although our Celestial

Empire possesses all things in prolific abundance

and lacks no product within its own borders. There

was therefore no need to import the manufactures of

outside barbarians in exchange for our own produce.

But as the tea, silk and porcelain which the Celestial

Empire produces, are absolute necessities to European nations and to yourselves, we have permitted,

as a signal mark of favour, that foreign hongs should

834

be established at Canton, so that your wants might

be supplied and your country thus participate in our

beneficence. But your Ambassador has now put forward new requests which completely fail to recognise

the Throne’s principle to ‘treat strangers from afar

with indulgence,’ and to exercise a pacifying control

over barbarian tribes, the world over. Moreover, our

dynasty, swaying the myriad races of the globe,

extends the same benevolence towards all. Your England is not the only nation trading at Canton. If other

nations, following your bad example, wrongfully

importune my ear with further impossible requests,

how will it be possible for me to treat them with easy

indulgence? Nevertheless, I do not forget the lonely

remoteness of your island, cut off from the world by

intervening wastes of sea, nor do I overlook your

excusable ignorance of the usages of our Celestial

Empire. I have consequently commanded my Ministers to enlighten your Ambassador on the subject,

and have ordered the departure of the mission. But I

have doubts that, after your Envoy’s return he may

fail to acquaint you with my view in detail or that he

may be lacking in lucidity, so that I shall now proceed

to take your requests seriatim and to issue my mandate on each question separately. In this way you

will, I trust, comprehend my meaning.

(1) Your Ambassador requests facilities for ships

of your nation to call at Ningpo, Chusan, Tientsin

and other places for purposes of trade. Until now

trade with European nations has always been conducted at Aomen, where the foreign hongs are established to store and sell foreign merchandise. Your

nation has obediently complied with this regulation

for years past without raising any objection. In none

of the other ports named have hongs been established, so that even if your vessels were to proceed

thither, they would have no means of disposing of

their cargoes. Furthermore, no interpreters are available, so you would have no means of explaining your

wants, and nothing but general inconvenience would

result. For the future, as in the past, I decree that

your request is refused and that the trade shall be

limited to Aomen.

(2) The request that your merchants may establish

a repository in the capital of my Empire for the storing and sale of your produce, in accordance with the

precedent granted to Russia, is even more impracticable than the last. My capital is the hub and centre

about which all quarters of the globe revolve. Its ordinances are most august and its laws are strict in the

extreme. The subjects of our dependencies have

never been allowed to open places of business in

Milestone Documents in World History

Document Text

Qianlong’s Letter to George III

are prevented, and a firm barrier is raised between my

subjects and those of other nations. The present

request is quite contrary to precedent; furthermore,

European nations have been trading with Canton for

a number of years and, as they make large profits, the

number of traders is constantly increasing. How

would it be possible to grant such a site to each country? The merchants of the foreign hongs are responsible to the local officials for the proceedings of barbarian merchants and they carry out periodical inspections. If these restrictions were withdrawn, friction

would inevitably occur between the Chinese and your

barbarian subjects, and the results would militate

against tile benevolent regard that I feel towards you.

From every point of view, therefore, it is best that the

regulations now in force should continue unchanged.

(5) Regarding your request for remission or

reduction of duties on merchandise discharged by

your British barbarian merchants at Aomen and distributed throughout the interior, there is a regular

tariff in force for barbarian merchants’ goods, which

applies equally to all European nations. It would be

as wrong to increase the duty imposed on your

nation’s merchandise on the ground that the bulk of

foreign trade is in your hands, as to make an exception in your case in the shape of specially reduced

duties. In future, duties shall be levied equitably

without discrimination between your nation and any

other, and, in order to manifest my regard, your barbarian merchants shall continue to be shown every

consideration at Aomen.

(6) As to your request that your ships shall pay the

duties leviable by tariff, there are regular rules in

force at the Canton Custom house respecting the

amounts payable, and since I have refused your

request to be allowed to trade at other ports, this

duty will naturally continue to be paid at Canton as

heretofore.

(7) Regarding your nation’s worship of the Lord of

Heaven, it is the same religion as that of other European nations. Ever since the beginning of history,

sage Emperors and wise rulers have bestowed on

China a moral system and inculcated a code, which

from time immemorial has been religiously observed

by the myriads of my subjects. There has been no

hankering after heterodox doctrines. Even the European (missionary) officials in my capital are forbidden to hold intercourse with Chinese subjects; they

are restricted within the limits of their appointed residences, and may not go about propagating their religion. The distinction between Chinese and barbarian

is most strict, and your Ambassador’s request that

Milestone Documents

Peking. Foreign trade has hitherto been conducted at

Aomen, because it is conveniently near to the sea,

and therefore an important gathering place for the

ships of all nations sailing to and fro. If warehouses

were established in Peking, the remoteness of your

country, lying far to the north-west of my capital,

would render transport extremely difficult.

Before Kiakhta was opened, the Russians were

permitted to trade at Peking, but the accommodation

furnished to them was only temporary. As soon as

Kiakhta was available, they were compelled to withdraw from Peking, which has been closed to their

trade these many years. Their frontier trade at

Kiakhta is on all fours with your trade at Aomen. Possessing facilities at the latter place, you now ask for

further privileges at Peking, although our dynasty

observes the severest restrictions respecting the

admission of foreigners within its boundaries, and

has never permitted the subjects of dependencies to

cross the Empire’s barriers and settle at will amongst

the Chinese people. This request is also refused.

(3) Your request for a small island near Chusan,

where your merchants may reside and goods be

warehoused, arises from your desire to develop trade.

As there are neither foreign hongs nor interpreters in

or near Chusan, where none of your ships have ever

called, such an island would be utterly useless for

your purposes. Every inch of the territory of our

Empire is marked on the map and the strictest vigilance is exercised over it all: even tiny islets and farlying sand-banks are clearly defined as part of the

provinces to which they belong. Consider, moreover,

that England is not the only barbarian land which

wishes to establish relations with our civilisation and

trade with our Empire: supposing that other nations

were all to imitate your evil example and beseech me

to present them each and all with a site for trading

purposes, how could I possibly comply? This also is a

flagrant infringement of the usage of my Empire and

cannot possibly be entertained.

(4) The next request, for a small site in the vicinity of Canton city, where your barbarian merchants

may lodge or, alternatively, that there be no longer any

restrictions over their movements at Aomen, has arisen from the following causes. Hitherto, the barbarian

merchants of Europe have had a definite locality

assigned to them at Aomen for residence and trade,

and have been forbidden to encroach an inch beyond

the limits assigned to that locality. Barbarian merchants having business with the hongs have never

been allowed to enter the city of Canton; by these

measures, disputes between Chinese and barbarians

835

Document Text

barbarians shall be given full liberty to disseminate

their religion is utterly unreasonable.

It may be, O King, that the above proposals have

been wantonly made by your Ambassador on his own

responsibility, or peradventure you yourself are ignorant of our dynastic regulations and had no intention

of transgressing them when you expressed these wild

ideas and hopes. I have ever shown the greatest condescension to the tribute missions of all States which

sincerely yearn after the blessings of civilisation, so

as to manifest my kindly indulgence. I have even

gone out of my way to grant any requests which were

in any way consistent with Chinese usage. Above all,

upon you, who live in a remote and inaccessible

region, far across the spaces of ocean, but who have

shown your submissive loyalty by sending this tribute

mission, I have heaped benefits far in excess of those

accorded to other nations. But the demands presented by your Embassy are not only a contravention of

dynastic tradition, but would be utterly improductive

of good result to yourself, besides being quite

impracticable. I have accordingly stated the facts to

you in detail, and it is your bounden duty reverently

to appreciate my feelings and to obey these instructions henceforward for all time, so that you may

enjoy the blessings of perpetual peace. If, after the

receipt of this explicit decree, you lightly give ear to

the representations of your subordinates and allow

your barbarian merchants to proceed to Chêkiang

and Tientsin, with the object of landing and trading

there, the ordinances of my Celestial Empire are

strict in the extreme, and the local officials, both civil

and military, are bound reverently to obey the law of

the land. Should your vessels touch the shore, your

merchants will assuredly never be permitted to land

or to reside there, but will be subject to instant

expulsion. In that event your barbarian merchants

will have had a long journey for nothing. Do not say

that you were not warned in due time! Tremblingly

obey and show no negligence! A special mandate!

Glossary

836

tribute missions

persons representing dependent states who appeared before the emperor bearing rare

and valuable items as evidence of submission to the Qing Dynasty

Swaying the wide

world

a reflection of the emperor’s belief his geopolitical importance far outweighed that of

Great Britain, continental Europe, and the rest of the known world

Milestone Documents in World History

1839

Lin Zexu’s “Moral Advice to

Queen Victoria”

“ The wealth of China is used to profit the barbarians.”

Overview

In 1839, in light of the growing level of

opium addiction in China under the Qing

Dynasty, Emperor Daoguang sent Commissioner Lin Zexu to Guangzhou (also called

Canton), Guangdong Province, and ordered

him to stop the smuggling and sale of opium

in China by Western, especially British,

merchants. While negotiating with Charles Elliot, the

British superintendent of trade, for his cooperation, Lin

wrote a letter in the traditional “memorial” form to the ruler

of Britain expressing China’s desire for peaceful resolution

of the opium trade. He used what limited even mistaken

knowledge he had newly acquired about his adversary in the

hope of evoking the latter’s sympathy and understanding.

Drawing on Confucian precepts as well as historical events,

he also reasoned forcefully on moral ground, trying to persuade the English monarch that he naturally would not

wish to ask of others what he himself did not want. The letter was, in effect, an ultimatum made by Commissioner Lin

on behalf of the Qing emperor to the English monarch,

delivering the unmistakable message that he and the Qing

government were determined to ban the selling and smoking of opium once and for all and at any cost.

After drafting and revising the letter, Commissioner Lin

asked his assistant and English missionaries and merchants

to translate it into English and present it to the British

king who was actually Queen Victoria, whose reign had

begun in 1837. Lin also circulated the letter as a public

announcement to the Western merchants in Guangzhou.

In the end, the letter was not delivered to the queen as he

had intended, nor was his hope for a peaceful solution to

the opium problem realized. Instead, the so-called First

Opium War broke out in 1840, which ended in the Qing

Dynasty’s defeat and Lin’s dismissal.

Context

From the late seventeenth century onward, international trade and commerce gained more and more importance

in the West. The demand for tea and porcelain from China

Lin Zexu’s “Moral Advice to Queen Victoria”

and for spices and indigo from India motivated many Europeans, especially the Dutch, Portuguese, and English, to

establish trade depots or factories in Asia. The success of

the emergent Industrial Revolution in England also fueled

the English ambition to sell manufactured products in Asia

in exchange for Asian goods. But most Asians, especially the

Chinese, were simply uninterested in reciprocating trade

with Western Europe. In 1793 Lord George Macartney, the

first British ambassador to China, approached Emperor

Qianlong and presented King George III’s wish to establish

diplomatic relations and expand trade between Britain and

China. The emperor, however, firmly rejected all the

requests made by the British embassy on the grounds that

China had always been a self-sufficient country and that it

had neither need for nor interest in foreign goods. At the

time, any foreign trade with the West was administered

through the Canton System, in which Western merchants

were allowed to sell their goods in Guangzhou only through

the Cohong (or Gonghang) merchants, who were the Chinese middlemen. Hoping to change the system and expand

trade, Europeans continued to send embassies to China

the Dutch in 1795, the Russians in 1806, and the British

again in 1816 all to no avail.

The Europeans repeatedly sent emissaries to China

because they wanted to sell more goods to the Chinese in

order to balance the growing trade deficit incurred through

the purchase of Chinese goods, especially tea. Through the

eighteenth century, tea imports in Britain had risen

sharply; from 1784 to 1785 they grew to over fifteen million pounds, from just over two pounds a century or so earlier. The British East India Company, which handled the

nation’s trade with China, began to grow tea in India in the

1820s but would not ship tea to Britain until 1858. Therefore, through the mid-nineteenth century almost all tea

had to be imported from China. Between 1811 and 1819,

British imports from China totaled over £72 million, of

which tea was worth £70 million.

Aside from diplomatic efforts, the British also searched

for and found an alternative to the currency of silver for the

purchase of tea and other Chinese goods: opium. Just as

Lord Macartney was pleading with Emperor Qianlong for

the establishment of trade relations, British merchants discovered this different and illicit way to address the mount-

933

Time Line

934

1600

■

December 31

The British East

India Company

is founded.

1760

■

The Canton

System is

established,

forbidding direct

access to trade

in China by

foreign

merchants.

1820

■

October 3

Emperor

Daoguang

ascends to the

Qing dynastic

throne in China.

1834

■

The monopoly

of the British

East India

Company on

trade with the

Far East ends.

1837

■

June 20

Queen Victoria

ascends to the

British throne.

1838

■

Commissioner

Lin Zexu is sent

by Emperor

Daoguang to

Guangdong to

halt the sale of

opium.

1839

■

Lin Zexu writes

an open letter to

Queen Victoria,

urging a

peaceful

resolution to the

opium trade.

■

The First Opium

War breaks out.

ing trade deficit with China. They began selling opium to

the Chinese even though it had been banned by Emperor

Yongzheng, Emperor Qianlong’s father, as early as 1729.

Thanks to opium sales, the silver inflow to China dropped

from over 26.6 million taels between 1801 and 1810 to

under 10 million taels between 1811 and 1820, or by about

63 percent. Later, as opium addiction spread rapidly in

China, silver began to flow out of the country to the West,

especially Britain; between 1821 and 1830 China paid out

2.3 million taels. And from 1831 to 1833, a period of merely three years, China paid an astonishing 9.9 million taels.

During the 1830s, therefore, Qing China began to suffer

seriously from the trade deficit with the West. The economic

toll of the growing opium sales and addiction in China was

twofold. First, as opium sales grew, sales in other areas of

trade dropped as a result. In his early career as governor of

Jiangsu Province, Lin Zexu observed that Chinese merchants

could sell only half of what they used to sell a decade or two

earlier. Second, the outflow of silver caused a financial crisis

in the country by altering the exchange rate between silver

and copper, which was used in people’s daily transactions.

The shortage of silver caused its value to appreciate, which

aggravated the tax burden on the people, because in paying

tax they had to exchange copper cash for silver. In the eighteenth century a string of 1,000 copper cash was equal to 1

tael of silver. By the early nineteenth century 1 tael of silver

was worth 1,500 copper cash, and in the mid nineteenth

century it was worth 2,700 copper cash.

While opium does have medicinal use, relieving pain and

allaying emotional distress, it is an addictive drug. Once the

habit is formed, the withdrawal symptoms can include

“extreme restlessness, chills, hot flushes, sneezing, sweating, salivation, running nose, and gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.” Furthermore, “there are severe cramps in the abdomen, legs, and

back; the bones ache; the muscles twitch; and the nerves

are on edge. Every symptom is in combat with another. The

addict is hungry, but he cannot eat; he is sleepy, but he cannot sleep” (Chang, p. 17). There can be little wonder, then,

that ever since Emperor Yongzheng banned its consumption

in the early eighteenth century, opium has remained contraband in China. During the early nineteenth century, when

opium smoking spread across social strata and addicts numbered in the millions, many observers grew alarmed, especially scholar-officials, who presented a number of “memorials” to Emperor Daoguang, urging him to adopt harsh

measures against the smuggling and selling of the drug. Lin

Zexu was one, and arguably the most eloquent, among these

scholar-officials. In one of his memorials, he argued vehemently that “if we continue to pamper it [opium smoking],

a few decades from now we shall not only be without soldiers to resist the enemy, but also in want of silver to provide an army” (Chang, p. 96). Others suggested legalizing

the drug to curb its abuse, but the proposal was rejected by

the emperor, who regarded opium as an evil poison.

There is no source directly explaining why opium smoking which entails first heating opium paste over a flame and

then smoking it through a long-stemmed pipe became so

Milestone Documents in World History

Lin Zexu’s “Moral Advice to Queen Victoria”

Time Line

1842

■

August 29

The Treaty of

Nanjing is

signed, ending

the First Opium

War as well as

the Canton

System.

1850

■

February 25

Emperor

Daoguang dies.

■

March 9

Emperor Xianfeng

ascends to the

Qing throne.

1856

■

The Second

Opium War

breaks out, to

last for four

years.

1858

■

August 2

Under the Act

for the Better

Government of

India, the British

East India

Company’s

functions are

transferred to

the Crown.

1874

■

January 1

The British East

India Company

closes its

business

operations.

Milestone Documents

popular among the Chinese beginning in the late eighteenth

century. Speculation holds that it might have had something

to do with tobacco smoking, imported from Latin America in

the previous century. When tobacco smoking was first introduced to mainland China by soldiers who returned from a

campaign in Taiwan, opium and tobacco were mixed and

smoked together. As opium’s therapeutic effects were

revealed, it gained in popularity, especially among people who

struggled with boredom or stress, such as eunuchs, wealthy

women, petty clerks, and examination takers. As time went

on, the habit of opium smoking spread to the leisure and

working classes alike for social relaxation. To abet sales, merchants prepared detailed accounts of means of consumption

in simple language, available to anyone who could read.

Nor has a convincing explanation been put forth for why,

despite the repeated edicts from the emperor and the government, opium smoking became so unstoppable in China.

Aside from the persistence of Western merchants in selling

the drug, it was generally believed that the Qing government had by then become corrupt and hence ineffective in

executing imperial orders. When a new imperial edict was

issued in 1813 banning opium smoking altogether, it was

actually quite harsh in punishing both smokers and sellers.

If caught, a smoker could be sentenced to one hundred

blows of the bamboo stick and forced to wear a heavy wooden collar in public for a month. Afraid of the severe consequences, the Cohong merchants who had monopolized the

trade with the Europeans ceased involvement, at least in

public. But small dealers quickly took their place, approaching European merchants directly in swift boats and then

distributing the drug through networks of local trade.

Apparently, this was a risky practice; to ensure its success,

both European merchants and Chinese dealers bribed officials for their connivance. Some officials even exploited the

trade by enforcing a fee per chest of opium. Whenever a

new anti-opium edict was issued from the central government, local officials, rather than carry it out, would increase

the fee for enriching themselves.

The British East India Company also played a dubious

role in the opium trade, to say the least. Some of its officials

did have qualms about smuggling the drug into China; the

company stopped sales at one point, only to allow their

resumption shortly after. For the company, the establishment of a long-standing opium monopoly in the Bengal

region was a major success of the British conquest of India.

In the 1780s the British East India Company took control

of opium sales and production in the English-controlled

areas of India. Shortly thereafter, the company also monopolized the trade with China. Hence, the company’s opium

production in India coincided with its intensified trade with

China. In light of the huge deficits it had incurred in buying tea from China, the company clearly had major incentive to engage in opium production, if not directly in its selling. In fact, thanks to the company’s excellent management

of its opium monopoly in India, Indian opium was regarded

by both dealers and smokers as representing high quality.

The profits made by the company through opium sales

would be directly used to purchase tea. A triangular trade

network, from Britain to India, India to China, and China

to Britain, thus formed. The company first bought (nominally) opium in India, selling it to private merchants, or

“country traders,” for smuggling into China; the merchants

then used the silver gained to buy tea, porcelain, and other

goods to sell back in Britain. This network helped to support

the entire British position in the Far East, especially the ruling of India. Thanks to opium, the company and the British

government not only corrected the earlier deficits in their

China trade but also reaped a good fortune.

The success of the British East India Company in monopolizing and profiting from the trade with China caused envy

935

The East India Company ruled British India from East India House until 1858.

among others. By 1834 the company’s monopoly of the trade

came to an end, and the trade’s being open to all comers

resulted in the rise of opium sales. In 1832 China imported

more than twenty-three thousand chests of opium (with each

chest containing between 130 and 160 pounds); the figure

rose to thirty thousand chests in 1835 and to forty thousand

chests in 1838. These increases drove Western merchants to

chafe more blatantly at the Canton System, the Qing government’s means of control of foreign trade, in the hope of prying open China’s door to the West, and merchants’ actions

were broadly sanctioned by the British government. After the

end of the British East India Company’s monopoly, British

merchants in China were represented by the superintendent

of trade. A government official, the superintendent often

refused to deal with the Cohong merchants, demanding

instead that he communicate directly with Qing officials. The

clash over opium sales thus became not simply a matter

between the Qing government and Western merchants but

rather one between Qing China and Great Britain.

About the Author

Born in Fuzhou, Fujian Province, in 1785, Lin Zexu

excelled in his study of the Chinese classics and in the civil

936

(© Museum of London)

service examinations; he earned the jinshi (“presented scholar”) degree in 1811 and subsequently became a member of

the Hanlin Academy, a prestigious institution of Confucian

learning in Beijing, the dynasty capital. Lin then launched a

successful career in government, serving in a range of posts

in various provinces. His commitment to high moral standards and integrity earned him the epithet of “Lin the Blue

Sky.” Prior to becoming the imperial commissioner, Lin was

the governor-general of Hunan and Hubei in 1837; in this

post he launched a vigorous campaign against opium smoking. He also repeatedly memorialized the emperor for taking

tough measures against opium sales. As commissioner, Lin

assembled scholars to compile the book Sizhouzhi (Treatise

on Four Continents), an effort to establish and disseminate

knowledge about Europe and the world. After Western merchants refused to obey his orders to surrender illicit opium,

he blockaded their enclave and eventually confiscated and

destroyed 2.6 million pounds of opium. The British government retaliated by sending a fleet to China, and the British

prevailed in battle. Angry over Lin’s action for its leading to

military conflict and defeat, Emperor Daoguang dismissed

him and exiled him to Xinjiang. Lin was later reinstated,

however, and ordered to deal with other difficult situations.

He died while traveling to Guangxi to administer a campaign

against the Taiping Rebellion in 1850.

Milestone Documents in World History

Explanation and Analysis of the Document

Lin Zexu’s “Moral Advice to Queen Victoria”

937

Milestone Documents

Lin Zexu’s letter to the British Crown starts by singing

praises to the Qing emperor for his grace and benevolence.

These praises reflect the long-entrenched Chinese notion

that China was the center of the world, or the “Zhongguo”

(Central Country/Middle Kingdom) in the cosmos. Out of

courtesy, Lin acknowledges in the second paragraph that

Britain is also a historical country with an honorable tradition. Yet this acknowledgment, too, builds on the Sinocentric conception of the world; he commends the “politeness

and submissiveness” of the British in delivering tributes

and offering “tributary memorials” to the ruler of the Celestial Empire China. He also deems that the British have

benefited considerably from these activities, a point he will

stress again later in the letter.

Paragraphs 3 5 directly address the problem that

prompted Lin to seek communication with the ruler of

Britain: the smuggling and selling of opium in China by

British merchants. Lin describes how his emperor is enraged

by the harm to the Chinese people caused by opium smoking and how he has been dispatched by the emperor to put

an end to the practice. He explains the punishment for the

Chinese who smoke and sell opium and notes that were his

emperor not so graceful, the same punishment could be

extended to British sellers. Lin had recently confiscated a

large amount of opium through the help of Charles Elliot,

the British superintendent of trade; his reporting this serves

as a warning because, as he reveals, the Qing Dynasty had,

in fact, promulgated new regulations, whereby if any Briton

was found selling opium, he would receive the same punishment as would a Chinese. Indeed, a major reason for Lin’s

writing and circulating this letter was to inform and warn the

British and other foreign merchants about the new regulations. In order to carry them out, he needed the help of the

British ruler, who “must be able to instruct the various barbarians to observe the law with care.”

In seeking to secure the aid of the British ruler, Lin

resorts to moral suasion in paragraphs 6 8. This is consistent with the teaching of Confucianism and Lin’s own character. His central argument draws on the Confucian precept

that, as phrased in paragraph 8, “naturally you would not

wish to give unto others what you yourself do not want.” But

in exercising this moral exhortation, Lin shows his limited as

well as mistaken knowledge about his adversary, and his mistakes invariably undercut the effect of his argument. He first

assumes that the sale and smoking of opium are forbidden in

Britain, which was erroneous, for most British then considered opium no more harmful to humans than alcohol. Second, he believes tea and rhubarb to be indispensable to the

health of the British, which was wrong, even though tea

drinking had become a national habit in Britain. Third, he

states that without Chinese silk, other textiles could not be

woven; this was clearly inaccurate. But even with these

seemingly egregious mistakes, Lin makes a strong point: The

British needed Chinese goods more than the Chinese did

British goods, so how could the British repay the benefits

from and benevolence of the Chinese by selling them the

poisonous drug? In paragraph 6 he asks passionately, “Where

is your conscience?” It would have been hard for the British

Crown to counter this line of argument.

After asking such acute questions, Lin softens his tone

in paragraph 9. He writes that perhaps the British ruler was

unaware that some wicked British subjects have been

involved in opium smuggling in China, since in the British

homeland, because of the king’s (that is, the queen’s) “honorable rule,” no opium is produced. He thus asks the British

ruler to extend the edict against planting opium from

Britain to India and to grow the “five grains” in its stead.

This plea is also made on the moral ground that for such a

virtuous course of action, “heaven must support you and the

spirits must bring you good fortune.” Lin’s notion that the

“five grains” are essential to humans and his belief in both

“Heaven” and “spirits” are distinctly Chinese.

Paragraphs 10 12 offer further explanation of the new

regulations from the imperial court by which the same punishments will be extended to the British if they continue

ignoring Lin’s anti-opium orders and policy. Central to these

explanations is an idea of jurisdiction that Lin takes for

granted (as do many sovereign nations today): A foreigner

who lives in another country must obey the laws of that

country rather than the laws of his own. That is, Lin repudiates the extraterritorial rights that the British then demanded from the Qing Dynasty and which they later obtained

through the First Opium War. Lin’s refusal of such privilege

in this letter does not draw on international law but follows

the same Confucian principle that you would not do unto

others what you yourself do not want done unto you, the line

of reasoning he used before. He asks the English ruler, “Suppose a man of another country comes to England to trade,

he still has to obey the English laws; how much more should

he obey in China the laws of the Celestial Dynasty?”

Before he actually carried out the new orders to punish

opium sellers with “decapitation or strangulation” Lin

wanted to exercise caution, which was why he decided to

write the letter in the first place. In paragraph 12, he again

reminds the reader of the kindness of his emperor. When

informed of the new regulations, Charles Elliot requested an

extension, Lin writes. After Lin forwarded the request to the

emperor, the emperor, out of “consideration and compassion,” actually agreed to grant the extension with additional

months of leeway. Lin thus hails his ruler’s “extraordinary

Celestial grace.” Yet with the benefit of hindsight, historians

may also interpret this “grace” as a sort of reluctance on the

part of the Qing ruler to confront the British militarily. In

other words, although the emperor ordered Lin to halt

opium sales in Guangzhou and Guangdong, he was not

ready to risk war with the British. If Lin’s letter amounted to

a last-ditch effort to solve the opium problem peacefully, this

approach was indeed favored and sanctioned by the emperor. It was said that Lin memorialized Emperor Daoguang

sometime in July 1839, enclosing in the memorial the letter

that he had drafted for the English ruler. On August 27,

Emperor Daoguang approved it. Lin then asked others to

translate it into English, publicized it around Guangzhou,

and looked for messengers to deliver it to Britain.

Illustration of an opium den in London

938

(© Museum of London)

Milestone Documents in World History

“