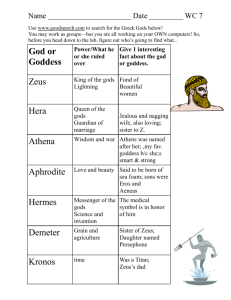

Aphrodite: The Goddess at Work in Archaic

advertisement